Otari-Wilton's Bush Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adaptation in the Lowveld Veld

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE Lucy Higgins 0507792K Adaptation in the Lowveld A comparative case study of the live-action to 3D animation filmic adaptation of Duncan MacNeillie’s Jock of the Bushveld A research report submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by coursework in Digital Animation University of the Witwatersrand Wits School of Arts – Digital Arts 15 November 2012 Supervisor: Hanli Geyser Higgins 1 Declaration I hereby declare that this dissertation is my own work. It is submitted for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been previously submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. Lucy Higgins 15th day of November, 2012 Higgins 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Hanli Geyser for her unwavering support throughout the course of this research project, her guidance has proved invaluable. I would also like to thank Christo Doherty for assisting me during the early stages of my proposal preparation. I would like to thank Duncan MacNeillie for taking time out of his busy schedule to grant me an interview and provide the basis upon which this entire report is built. Thank you to my parents, Michael and Rebecca, and my sister Charlotte for their support, encouragement and understanding, as well as financial support. Lastly, thank you to Aidan, Sandy and Greg for all the belief and encouragement you have shown me during this process. Higgins 3 Contents Introduction: .......................................................................................................................................... -

Australian Settler Bush Huts and Indigenous Bark-Strippers: Origins and Influences

Australian settler bush huts and Indigenous bark-strippers: Origins and influences Ray Kerkhove and Cathy Keys [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This article considers the history of the Australian bush hut and its common building material: bark sheeting. It compares this with traditional Aboriginal bark sheeting and cladding, and considers the role of Aboriginal ‘bark strippers’ and Aboriginal builders in establishing salient features of the bush hut. The main focus is the Queensland region up to the 1870s. Introduction For over a century, studies of vernacular architectures in Australia prioritised European high-style colonial vernacular traditions.1 Critical analyses of early Australian colonial vernacular architecture, such as the bush or bark huts of early settlers, were scarce.2 It was assumed Indigenous influences on any European-Australian architecture could not have been consequential.3 This mirrored the global tendency of architectural research, focusing on Western tradi- tions and overlooking Indigenous contributions.4 Over the last two decades, greater appreciation for Australian Indigenous archi- tectures has arisen, especially through Paul Memmott’s ground-breaking Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley: The Indigenous Architecture of Australia (2007). This was recently enhanced by Our Voices: Indigeneity and Architecture (2018) and the Handbook of Indigenous Architecture (2018). The latter volumes located architec- tural expressions of Indigenous identity within broader international movements.5 Despite growing interest in the crossover of Australian Indigenous architectural expertise into early colonial vernacular architectures,6 consideration of intercultural architectural exchange remains limited.7 This article focuses on the early settler Australian bush hut – specifically its widespread use of bark sheets as cladding. -

Quintessential Australian Bush and Outback

LUXURY LODGES OF AUSTRALIA SUGGESTED ITINERARIES Darwin QUINTESSENTIAL 3 Kununurra Alice Springs Ayers Rock (Uluru) + Brisbane AUSTRALIAN BUSH 1 2 AND OUTBACK Sydney EXPLORATION TOTAL SUGGESTED NIGHTS: 9 nights Plus suggested add-on and extra nights at arrival or departure if desired. Meander off the beaten track with this quintessential Australian itinerary, exploring the bush and outback with the support of a knowledgeable and passionate team of hosts and guides. This itinerary encourages guests immerse themselves in Australia’s environment, wildlife and diverse natural landscapes. FROM BRISBANE DRIVE 2 HRS TO SPICERS PEAK LODGE. 1 Spicers Peak Lodge Scenic Rim, South East Queensland (3 Nights) Located on 8000 acres at the peak of the ridge, with breathtaking views of the World Heritage listed Main Range National Park and Scenic Rim, Spicers Peak Lodge is Queensland’s highest mountain lodge retreat. A selection of must do’s • Arrange for a picnic hamper to be delivered to one of many scenic picnic locations around the 8,000 acre property. A table can be set for guests to arrive at the location, after a bike ride or walk, to chilled champagne, stunning views and nothing to unpack. • Complimentary mountain bikes are provided to experience the great outdoors at its best. There are plenty of opportunities for the experienced fit biker as well as the more leisurely rider to enjoy this bush experience. • Star Gazing – In the evenings the magnificence of the Southern sky spreads out all around. Learn about the various constellations from your local guide. 2 HR DRIVE TO BRISBANE AIRPORT, 1.5 HR FLIGHT TO SYDNEY AIRPORT, 3 HR DRIVE TO EMIRATES WOLGAN VALLEY OR 30 MIN PRIVATE HELICOPTER TRANSFER. -

19Th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence As the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History Spring 5-7-2011 19th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence as the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity Kevin W. Hudson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hudson, Kevin W., "19th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence as the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2011. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/45 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 19TH CENTURY TRAGEDY, VICTORY, AND DIVINE PROVIDENCE AS THE FOUNDATIONS OF AN AFRIKANER NATIONAL IDENTITY by KEVIN W. HUDSON Under the DireCtion of Dr. Mohammed Hassen Ali and Dr. Jared Poley ABSTRACT Apart from a sense of racial superiority, which was certainly not unique to white Cape colonists, what is clear is that at the turn of the nineteenth century, Afrikaners were a disparate group. Economically, geographically, educationally, and religiously they were by no means united. Hierarchies existed throughout all cross sections of society. There was little political consciousness and no sense of a nation. Yet by the end of the nineteenth century they had developed a distinct sense of nationalism, indeed of a volk [people; ethnicity] ordained by God. The objective of this thesis is to identify and analyze three key historical events, the emotional sentiments evoked by these nationalistic milestones, and the evolution of a unified Afrikaner identity that would ultimately be used to justify the abhorrent system of apartheid. -

SECONDARY Education Resource

Shearing the rams painted at Brocklesby station, Corowa, New South Wales, and Melbourne, 1888–90 oil on canvas mounted on board 121.9 x 182.6 cm National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest Fund, 1932 SECONDARY Education resource Secondary Education Resource 1 For teachers How to use this secondary student learning resource This extraordinary exhibition CURRICULUM ALIGNMENT brings together Tom Roberts’ most famous paintings loved by All the themes in the Tom Roberts exhibition can be used with visual arts students from Year 7–10 and beyond. all Australians. Paintings such as Some may be more relevant to specific years given connections to other learning areas such as History and Shearing the rams 1888–90 and Civics and Citizenship at the same level as outlined under A break away! 1891 are among each theme that follows. the nation’s best-known works The Arts – Visual Arts: Year 7 and 8 of art. • Experiment with visual arts conventions and techniques (ACAVAM118) Tom Roberts is a major exhibition of works from the • Develop ways to enhance their intentions as artists national collection as well as private and public collections through exploration of how artists use materials, from around Australia. techniques, technologies and processes (ACAVAM119) • Develop planning skills for art-making by exploring The secondary student learning resource for the Tom techniques and processes used by different artists Roberts exhibition highlights the relevance of Roberts’ (ACAVAM120) oeuvre to today’s contemporary world. Themes explored include Australian life, landscape, portraiture, Federation • Practise techniques and processes to enhance and making a nation, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representation of ideas in their art-making (ACAVAM121) histories, immigration and the influences of other artists. -

The Vocabulary of Australian English

THE VOCABULARY OF AUSTRALIAN ENGLISH Bruce Moore Australian National Dictionary Centre Australian National University The vocabulary of Australian English comes from many sources. This document outlines some of the most important sources of Australian words, and some of the important historical events that have shaped the creation of Australian words. At times, reference is made to the Australian Oxford Dictionary (OUP 1999) edited by Bruce Moore. 1. BORROWINGS FROM AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES ...2 2. ENGLISH FORMATIONS .....................................................................7 3. THE CONVICT ERA ...........................................................................11 4. BRITISH DIALECT .............................................................................15 5. BRITISH SLANG ................................................................................17 6. GOLD .................................................................................................18 7. WARS.................................................................................................21 © Australian National Dictionary Centre Page 1 of 24 1. BORROWINGS FROM AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES In 1770 Captain James Cook was forced to beach the Endeavour for repairs near present-day Cooktown, after the ship had been damaged on reefs. He and Joseph Banks collected a number of Aboriginal words from the local Guugu Yimidhirr people. One of these words was kangaroo, the Guugu Yimidhirr name for the large black or grey kangaroo Macropus -

SPELLING out P a UNIFIED SYNTAX of AFRIKAANS ADPOSITIONS and V-PARTICLES by Erin Pretorius Dissertation Presented for the Degree

SPELLING OUT P A UNIFIED SYNTAX OF AFRIKAANS ADPOSITIONS AND V-PARTICLES by Erin Pretorius Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisors Prof Theresa Biberauer (Stellenbosch University) Prof Norbert Corver (University of Utrecht) Co-supervisors Dr Johan Oosthuizen (Stellenbosch University) Dr Marjo van Koppen (University of Utrecht) December 2017 This dissertation was completed as part of a Joint Doctorate with the University of Utrecht. Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2017 Date The financial assistance of the South African National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. The author also wishes to acknowledge the financial assistance provided by EUROSA of the European Union, and the Foundation Study Fund for South African Students of Zuid-Afrikahuis. Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za For Helgard, my best friend and unconquerable companion – all my favourite spaces have you in them; thanks for sharing them with me For Hester, who made it possible for me to do what I love For Theresa, who always takes the stairs Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT Elements of language that are typically considered to have P (i.e. -

CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIA 5. Sydney Or the Bush? Chris Baker

CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIA 5. Sydney or the Bush? Chris Baker From the Monash University National Centre for Australian Studies course, developed with Open Learning Australia In the fifth week of the course, Chris Baker argues that while Australia is the most urbanized nation on earth, the ‘bush’ has had a great influence on the national psyche. What is it like to live in the great Australian cities today and how are they changing? Why does the bush have such an influence on Australian politics, and are Australians really exiles from the empty forests and plains of the interior? Chris Baker is a lecturer at the National Centre for Australian Studies, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. 5.1 Suburbia 5.2 The Great Australian Dream 5.3 Triumph of technology 5.4 The bush 5.5 Urban and bush collide 5.6 Further reading 5.1 Suburbia Sydney or the bush!, all or nothing, as in making a do or die attempt, gambling against the odds, etc. Macquarie Dictionary Book of (Australian) Slang Most Australians live in the great suburban sprawl that surrounds the cities. For the average suburban dweller a quarter acre block of land, a Victa motor mower, a brick veneer bungalow, a Hill’s clothes hoist and the family car have traditionally defined the urban lifestyle. The great expanse of suburbia has resulted in Australian cities covering vast areas making them, in geographic terms, some of the largest cities on earth. Explore the Nation Gallery at the National Museum of Australia. Overall standards of living in the suburbs are high, with per capita car ownership ranking with the United States and the provision of services such as libraries, schools shopping malls, sporting and communication facilities, water and sewerage being provided to most Australians. -

Calypso and the Bush

Calypso and the Bush PETER OOLEY Flinders University of South Australia his paper compares some of the lyrics from two apparendy radically different song codes - calypso from Tr inidad and Tobago in the postcolonial Caribbean, and the bushT ballad from white setder Australia. I am using two differentalthough interlocking time fr ames here. The bush ballad belongs primarily to the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, while calypso sung in French patois dates as far back as the eighteenth century but only moved into English and began to achieve prominence at the beginning of the twentieth. Both song codes developed in environments with very different histories and very different colonising situations. There are, however, some interesting similarities. In both regions the indigenous people were almost totally erased and their lands occupied by new groups displaced from their own homelands. Australiawas a dumping ground for white convicts and then a 'land of opportunity' for immigrants, while Trinidad and Tobago, in addition to a mixed race population of English, French, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, Indian and Chinese colonists, received a huge influx of black Mrican slaves - mainly under Spanish rule during the second half of the eighteenth century - until the island passed into British hands in 1797. The people of both Trinidad and Tobago and Australia, then, have, in different ways and circumstances, been owned and controlled by England in its role as imperial power, and this shared subjection to colonisation provides a background to this comparison of calypso and the bush ballad. The main assumption here is that both song forms have, in their respective countries, played a significant part in creating and representing imagined ideas of a national culture. -

Download Document

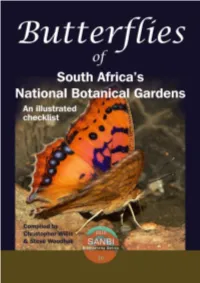

SANBI Biodiversity Series 16 Butterflies of South Africa’s National Botanical Gardens An illustrated checklist compiled by Christopher K. Willis & Steve E. Woodhall Pretoria 2010 SANBI Biodiversity Series The South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) was established on 1 Sep- tember 2004 through the signing into force of the National Environmental Manage- ment: Biodiversity Act (NEMBA) No. 10 of 2004 by President Thabo Mbeki. The Act expands the mandate of the former National Botanical Institute to include responsibili- ties relating to the full diversity of South Africa’s fauna and flora, and builds on the internationally respected programmes in conservation, research, education and visitor services developed by the National Botanical Institute and its predecessors over the past century. The vision of SANBI: Biodiversity richness for all South Africans. SANBI’s mission is to champion the exploration, conservation, sustainable use, appre- ciation and enjoyment of South Africa’s exceptionally rich biodiversity for all people. SANBI Biodiversity Series publishes occasional reports on projects, technologies, work- shops, symposia and other activities initiated by or executed in partnership with SANBI. Photographs: Steve Woodhall, unless otherwise noted Technical editing: Emsie du Plessis Design & layout: Sandra Turck Cover design: Sandra Turck Cover photographs: Front: Pirate (Christopher Willis) Back, top: African Leaf Commodore (Christopher Willis) Back, centre: Dotted Blue (Steve Woodhall) Back, bottom: Green-veined Charaxes (Christopher Willis) Citing this publication WILLIS, C.K. & WOODHALL, S.E. (Compilers) 2010. Butterflies of South Africa’s National Botanical Gardens. SANBI Biodiversity Series 16. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. ISBN 978-1-919976-57-0 © Published by: South African National Biodiversity Institute. -

Radio, Community and Identity in South Africa: a Rhizomatic Study of Bush Radio in Cape Town

RADIO, COMMUNITY AND IDENTITY IN SOUTH AFRICA: A RHIZOMATIC STUDY OF BUSH RADIO IN CAPE TOWN A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Tanja Estella Bosch November 2003 ©2003 Tanja Estella Bosch All Rights Reserved This dissertation entitled RADIO, COMMUNITY AND IDENTITY IN SOUTH AFRICA: A RHIZOMATIC STUDY OF BUSH RADIO IN CAPE TOWN BY TANJA E. BOSCH has been approved for the School of Telecommunications and The College of Communication by Jenny Nelson Associate Professor, Telecommunications Kathy Krendl Dean, College of Communication BOSCH, TANJA. E. PhD. November 2003. Telecommunications. Radio, community and identity in South Africa: A rhizomatic study of Bush Radio in Cape Town (289pp). Director of Dissertation: Jenny Nelson This dissertation deals with community radio in South Africa, before and after democratic elections in 1994. Adopting a case study approach and drawing on ethnographic methodology, the dissertation outlines the history of Bush Radio, the oldest community radio project in Africa. To demonstrate how Bush Radio creates community, this dissertation focuses on several cases within Bush Radio. The use of hip-hop for social change is explored. Framed within theories of entertainment-education and behavior change, the dissertation explores specific programs on-air and outreach programs offered by the station. This dissertation also looks at kwaito music, a new hybrid musical form that emerged in South Africa post- apartheid. In particularly, the dissertation argues that Bush Radio uses kwaito music in the consolidation of a black identity in South Africa. -

Rural Culture and Australian History: Myths and Realities

Rural Culture and Australian History: Myths and Realities RICHARD W ATERHOUSE* In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Australia's European inhabitants conceived of the Bush as providing a range of economic opportunities in terms of pastoralism, farming and mining. 'I believe a man with one or two thousand may make a fortune in a very few years ... ', wrote Frank B ailey in 1869 from rural Queensland to his sister Alice in England, 'if he goes the right way to work'. Such sentiments encapsulate the aspirations of generations of those who established rural enterprises.! What strengthened these conceptions of rural Australia as a place of opportunity was the extension of modem communication and transport systems in the form of the telegraph and railway lines to many rural areas. Such developments provided rural Australia with access to modem culture, modern values and, most important of all, modem markets. Moreover, while the impact of industrialisation on Australian secondary industry in the late nineteenth century remained modest, highly advanced technology was applied to our rural industries. Ironically, large wheat and sheep properties more closely resembled modem factories than the workshops that passed for 'factories' in Sydney and Melbourne. So large stations, which in the shearing season might employ in excess of 150 men, were fitted with scouring plants, steam presses and dumping machinery, their wool sheds included dozens of electric powered shearing machines, and conveyor belts were used to carry the shorn fleece to the wool room. Such * Richard Waterhouse is Professor of History and Head, School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry, University of Sydney.