Phospholipid:Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase: an Enzyme That Catalyzes the Acyl-Coa-Independent Formation of Triacylglycerol in Yeast and Plants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Novo Biosynthesis of Terminal Alkyne-Labeled Natural Products

De novo biosynthesis of terminal alkyne-labeled natural products Xuejun Zhu1,2, Joyce Liu2,3, Wenjun Zhang1,2,4* 1Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, 2Energy Biosciences Institute, 3Department of Bioengineering, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. 4Physical Biosciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. *e-mail:[email protected] 1 Abstract: The terminal alkyne is a functionality widely used in organic synthesis, pharmaceutical science, material science, and bioorthogonal chemistry. This functionality is also found in acetylenic natural products, but the underlying biosynthetic pathways for its formation are not well understood. Here we report the characterization of the first carrier protein- dependent terminal alkyne biosynthetic machinery in microbes. We further demonstrate that this enzymatic machinery can be exploited for the in situ generation and incorporation of terminal alkynes into two natural product scaffolds in E. coli. These results highlight the prospect for tagging major classes of natural products, including polyketides and polyketide/non-ribosomal peptide hybrids, using biosynthetic pathway engineering. 2 Natural products are important small molecules widely used as drugs, pesticides, herbicides, and biological probes. Tagging natural products with a unique chemical handle enables the visualization, enrichment, quantification, and mode of action study of natural products through bioorthogonal chemistry1-4. One prevalent bioorthogonal reaction is -

Peroxisomal Fatty Acid Beta-Oxidation in Relation to the Accumulation Of

Peroxisomal fatty acid beta-oxidation in relation to the accumulation of very long chain fatty acids in cultured skin fibroblasts from patients with Zellweger syndrome and other peroxisomal disorders. R J Wanders, … , A W Schram, J M Tager J Clin Invest. 1987;80(6):1778-1783. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI113271. Research Article The peroxisomal oxidation of the long chain fatty acid palmitate (C16:0) and the very long chain fatty acids lignocerate (C24:0) and cerotate (C26:0) was studied in freshly prepared homogenates of cultured skin fibroblasts from control individuals and patients with peroxisomal disorders. The peroxisomal oxidation of the fatty acids is almost completely dependent on the addition of ATP, coenzyme A (CoA), Mg2+ and NAD+. However, the dependency of the oxidation of palmitate on the concentration of the cofactors differs markedly from that of the oxidation of lignocerate and cerotate. The peroxisomal oxidation of all three fatty acid substrates is markedly deficient in fibroblasts from patients with the Zellweger syndrome, the neonatal form of adrenoleukodystrophy and the infantile form of Refsum disease, in accordance with the deficiency of peroxisomes in these patients. In fibroblasts from patients with X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy the peroxisomal oxidation of lignocerate and cerotate is impaired, but not that of palmitate. Competition experiments indicate that in fibroblasts, as in rat liver, distinct enzyme systems are responsible for the oxidation of palmitate on the one hand and lignocerate and cerotate on the other hand. Fractionation studies indicate that in rat liver activation of cerotate and lignocerate to cerotoyl-CoA and lignoceroyl-CoA, respectively, occurs in two subcellular fractions, the endoplasmic reticulum and the peroxisomes but not in the mitochondria. -

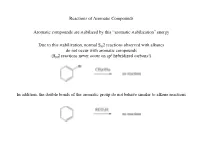

2 Reactions Observed with Alkanes Do Not Occur with Aromatic Compounds 2 (SN2 Reactions Never Occur on Sp Hybridized Carbons!)

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Aromatic compounds are stabilized by this “aromatic stabilization” energy Due to this stabilization, normal SN2 reactions observed with alkanes do not occur with aromatic compounds 2 (SN2 reactions never occur on sp hybridized carbons!) In addition, the double bonds of the aromatic group do not behave similar to alkene reactions Aromatic Substitution While aromatic compounds do not react through addition reactions seen earlier Br Br Br2 Br2 FeBr3 Br With an appropriate catalyst, benzene will react with bromine The product is a substitution, not an addition (the bromine has substituted for a hydrogen) The product is still aromatic Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Aromatic compounds react through a unique substitution type reaction Initially an electrophile reacts with the aromatic compound to generate an arenium ion (also called sigma complex) The arenium ion has lost aromatic stabilization (one of the carbons of the ring no longer has a conjugated p orbital) Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution In a second step, the arenium ion loses a proton to regenerate the aromatic stabilization The product is thus a substitution (the electrophile has substituted for a hydrogen) and is called an Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Energy Profile Transition states Transition states Intermediate Potential E energy H Starting material Products E Reaction Coordinate The rate-limiting step is therefore the formation of the arenium ion The properties of this arenium ion therefore control electrophilic aromatic substitutions (just like any reaction consider the stability of the intermediate formed in the rate limiting step) 1) The rate will be faster for anything that stabilizes the arenium ion 2) The regiochemistry will be controlled by the stability of the arenium ion The properties of the arenium ion will predict the outcome of electrophilic aromatic substitution chemistry Bromination To brominate an aromatic ring need to generate an electrophilic source of bromine In practice typically add a Lewis acid (e.g. -

Organic Chemistry/Fourth Edition: E-Text

CHAPTER 17 ALDEHYDES AND KETONES: NUCLEOPHILIC ADDITION TO THE CARBONYL GROUP O X ldehydes and ketones contain an acyl group RC± bonded either to hydrogen or Ato another carbon. O O O X X X HCH RCH RCRЈ Formaldehyde Aldehyde Ketone Although the present chapter includes the usual collection of topics designed to acquaint us with a particular class of compounds, its central theme is a fundamental reaction type, nucleophilic addition to carbonyl groups. The principles of nucleophilic addition to alde- hydes and ketones developed here will be seen to have broad applicability in later chap- ters when transformations of various derivatives of carboxylic acids are discussed. 17.1 NOMENCLATURE O X The longest continuous chain that contains the ±CH group provides the base name for aldehydes. The -e ending of the corresponding alkane name is replaced by -al, and sub- stituents are specified in the usual way. It is not necessary to specify the location of O X the ±CH group in the name, since the chain must be numbered by starting with this group as C-1. The suffix -dial is added to the appropriate alkane name when the com- pound contains two aldehyde functions.* * The -e ending of an alkane name is dropped before a suffix beginning with a vowel (-al) and retained be- fore one beginning with a consonant (-dial). 654 Back Forward Main Menu TOC Study Guide TOC Student OLC MHHE Website 17.1 Nomenclature 655 CH3 O O O O CH3CCH2CH2CH CH2 CHCH2CH2CH2CH HCCHCH CH3 4,4-Dimethylpentanal 5-Hexenal 2-Phenylpropanedial When a formyl group (±CHœO) is attached to a ring, the ring name is followed by the suffix -carbaldehyde. -

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just Like an Alkene, Benzene Has Clouds of Electrons Above and Below Its Sigma Bond Framework

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just like an alkene, benzene has clouds of electrons above and below its sigma bond framework. Although the electrons are in a stable aromatic system, they are still available for reaction with strong electrophiles. This generates a carbocation which is resonance stabilized (but not aromatic). This cation is called a sigma complex because the electrophile is joined to the benzene ring through a new sigma bond. The sigma complex (also called an arenium ion) is not aromatic since it contains an sp3 carbon (which disrupts the required loop of p orbitals). Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page1 The loss of aromaticity required to form the sigma complex explains the highly endothermic nature of the first step. (That is why we require strong electrophiles for reaction). The sigma complex wishes to regain its aromaticity, and it may do so by either a reversal of the first step (i.e. regenerate the starting material) or by loss of the proton on the sp3 carbon (leading to a substitution product). When a reaction proceeds this way, it is electrophilic aromatic substitution. There are a wide variety of electrophiles that can be introduced into a benzene ring in this way, and so electrophilic aromatic substitution is a very important method for the synthesis of substituted aromatic compounds. Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page2 Bromination of Benzene Bromination follows the same general mechanism for the electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS). Bromine itself is not electrophilic enough to react with benzene. But the addition of a strong Lewis acid (electron pair acceptor), such as FeBr3, catalyses the reaction, and leads to the substitution product. -

Using Dynamic Combinatorial Chemistry to Construct Novel Thioester and Disulfide Lipids

Using dynamic combinatorial chemistry to construct novel thioester and disulfide lipids A dissertation submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of MSc by Research Chemistry In the Faculty of Science and Engineering 2017 Jack A. Yung School of Chemistry Table of Contents List of figures, tables and equations 5 Symbols and abbreviations 10 Abstract 12 Declaration 13 Copyright statement 13 Acknowledgements 14 The author 14 Chapter 1. Introduction 15 1.1 The cell membrane 16 1.1.1 Function and composition 16 1.2 Membrane lipids 16 1.2.1 Lipid classification 16 1.2.2 Amphiphiles 17 1.2.3 Glycolipids 17 1.2.4 Sterols 18 1.2.5 Phospholipids 19 1.3 Lipid vesicles 20 1.3.1 Supramolecular self-assembly 20 1.3.2 Interaction free energies 21 1.3.3 Framework for the theory of self-assembly 22 1.3.4 Micelles 23 1.3.5 Lipid bilayers 24 1.3.6 Vesicles 25 1.3.7 Phase-transition temperature 27 1.4 Amphiphilic building blocks 27 1.5 Thioesters 29 1.5.1 Thioester reactivity 29 1.5.2 Trans-thioesterification 30 1.5.3 Thioester exchange reactions in DCC 31 1.6 Disulfides 32 2 1.6.1 Disulfide reactivity 32 1.6.2 Thiol-disulfide interchange reactions 32 1.6.3 Disulfide exchange reactions in DCC 33 1.7 Pre-biotic lipids 34 1.7.1 Sources of pre-biotic organic compounds 34 1.7.2 The first pre-biotic membrane structure 36 1.7.3 The role of sulfur in pre-biotic chemistry 36 1.8 Artificially designed vesicles 37 1.8.1 Applications of artificially designed vesicles 37 1.8.2 Zeta-potential 37 1.8.3 Vesicle design 38 1.9 Targets 39 1.9.1 Aims 39 Chapter 2. -

(10) Patent No.: US 8119385 B2

US008119385B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,119,385 B2 Mathur et al. (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 21, 2012 (54) NUCLEICACIDS AND PROTEINS AND (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................ 435/212:530/350 METHODS FOR MAKING AND USING THEMI (58) Field of Classification Search ........................ None (75) Inventors: Eric J. Mathur, San Diego, CA (US); See application file for complete search history. Cathy Chang, San Diego, CA (US) (56) References Cited (73) Assignee: BP Corporation North America Inc., Houston, TX (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS c Mount, Bioinformatics, Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Har (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this bor New York, 2001, pp. 382-393.* patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Spencer et al., “Whole-Genome Sequence Variation among Multiple U.S.C. 154(b) by 689 days. Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa” J. Bacteriol. (2003) 185: 1316 1325. (21) Appl. No.: 11/817,403 Database Sequence GenBank Accession No. BZ569932 Dec. 17. 1-1. 2002. (22) PCT Fled: Mar. 3, 2006 Omiecinski et al., “Epoxide Hydrolase-Polymorphism and role in (86). PCT No.: PCT/US2OO6/OOT642 toxicology” Toxicol. Lett. (2000) 1.12: 365-370. S371 (c)(1), * cited by examiner (2), (4) Date: May 7, 2008 Primary Examiner — James Martinell (87) PCT Pub. No.: WO2006/096527 (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Kalim S. Fuzail PCT Pub. Date: Sep. 14, 2006 (57) ABSTRACT (65) Prior Publication Data The invention provides polypeptides, including enzymes, structural proteins and binding proteins, polynucleotides US 201O/OO11456A1 Jan. 14, 2010 encoding these polypeptides, and methods of making and using these polynucleotides and polypeptides. -

Structure and Functional Diversity of GCN5-Related N-Acetyltransferases (GNAT)

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Structure and Functional Diversity of GCN5-Related N-Acetyltransferases (GNAT) Abu Iftiaf Md Salah Ud-Din 1, Alexandra Tikhomirova 1 and Anna Roujeinikova 1,2,* 1 Infection and Immunity Program, Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute; Department of Microbiology, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia; [email protected] (A.I.M.S.U.-D.); [email protected] (A.T.) 2 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-9902-9194; Fax: +61-3-9902-9222 Academic Editor: Claudiu T. Supuran Received: 30 May 2016; Accepted: 20 June 2016; Published: 28 June 2016 Abstract: General control non-repressible 5 (GCN5)-related N-acetyltransferases (GNAT) catalyze the transfer of an acyl moiety from acyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) to a diverse group of substrates and are widely distributed in all domains of life. This review of the currently available data acquired on GNAT enzymes by a combination of structural, mutagenesis and kinetic methods summarizes the key similarities and differences between several distinctly different families within the GNAT superfamily, with an emphasis on the mechanistic insights obtained from the analysis of the complexes with substrates or inhibitors. It discusses the structural basis for the common acetyltransferase mechanism, outlines the factors important for the substrate recognition, and describes the mechanism of action of inhibitors of these enzymes. It is anticipated that understanding of the structural basis behind the reaction and substrate specificity of the enzymes from this superfamily can be exploited in the development of novel therapeutics to treat human diseases and combat emerging multidrug-resistant microbial infections. -

Catalytic Mechanism of Perosamine N-Acetyltransferase Revealed by High-Resolution X-Ray Crystallographic Studies and Kinetic Analyses James B

Article pubs.acs.org/biochemistry Catalytic Mechanism of Perosamine N-Acetyltransferase Revealed by High-Resolution X-ray Crystallographic Studies and Kinetic Analyses James B. Thoden,† Laurie A. Reinhardt,† Paul D. Cook,‡ Patrick Menden,§ W. W. Cleland,*,† and Hazel M. Holden*,† † Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, United States ‡ Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Mount Union, Alliance, Ohio 44601, United States § McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, United States ABSTRACT: N-Acetylperosamine is an unusual dideoxysugar found in the O-antigens of some Gram-negative bacteria, including the pathogenic Escherichia coli strain O157:H7. The last step in its biosynthesis is catalyzed by PerB, an N-acetyltransferase belonging to the left-handed β-helix superfamily of proteins. Here we describe a combined structural and functional investigation of PerB from Caulobacter crescentus. For this study, three structures were determined to 1.0 Å resolution or better: the enzyme in complex with CoA and GDP-perosamine, the protein with bound CoA and GDP-N-acetylperosamine, and the enzyme containing a tetrahedral transition state mimic bound in the active site. Each subunit of the trimeric enzyme folds into two distinct regions. The N-terminal domain is globular and dominated by a six-stranded mainly parallel β-sheet. It provides most of the interactions between the protein and GDP-perosamine. The C-terminal domain consists of a left-handed β-helix, which has nearly seven turns. This region provides the scaffold for CoA binding. On the basis of these high-resolution structures, site-directed mutant proteins were constructed to test the roles of His 141 and Asp 142 in the catalytic mechanism. -

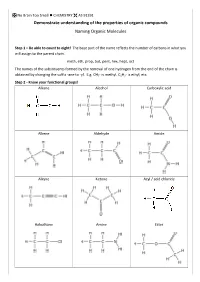

IUPAC Naming

No Brain Too Small CHEMISTRY AS 91391 Demonstrate understanding of the properties of organic compounds Naming Organic Molecules Step 1 – Be able to count to eight! The base part of the name reflects the number of carbons in what you will assign to the parent chain. meth, eth, prop, but, pent, hex, hept, oct The names of the substituents formed by the removal of one hydrogen from the end of the chain is obtained by changing the suffix -ane to -yl. E.g. CH3- is methyl, C2H5- is ethyl, etc. Step 2 - Know your functional groups! Alkane Alcohol Carboxylic acid Alkene Aldehyde Amide Alkyne Ketone Acyl / acid chloride Haloalkane Amine Ester No Brain Too Small CHEMISTRY AS 91391 This is NOT an exhaustive list of rules but a guide for L3 NCEA. Identify the principle functional group in the structure. If there is only ONE functional group then this is the principle functional group e.g. CH3CH2CH2COOH will have the suffix -oic acid as the carboxylic acid is the principle functional group. In cases where compounds have more than one functional group, then the principle functional group is decided by a priority order. carboxylic acids > acid derivatives* > aldehydes > ketones > alcohols > amines *esters, acyl/acid chlorides and amides 3-hydroxybutanoic acid 4-aminopentanoic acid as the carboxylic acid functional group takes priority Fluoro-, chloro-, bromo-, iodo- and alkyl groups have “no priority”. Their numbering is governed by the lowest sum rule. 2,3-dichloro-4-methylhexane and NOT 4,5-dichloro-2-methylhexane (as 2+3+4 = 9 whereas 2+4+5 = 11) No Brain Too Small CHEMISTRY AS 91391 Rules 1. -

A User's Guide to the Thiol-Thioester Exchange in Organic Media: Scope, Limitations, and Applications in Material Science

Polymer Chemistry A User's Guide to the Thiol-Thioester Exchange in Organic Media: Scope, Limitations, and Applications in Material Science Journal: Polymer Chemistry Manuscript ID PY-ART-07-2018-001031.R1 Article Type: Paper Date Submitted by the Author: 06-Aug-2018 Complete List of Authors: Worrell, Brady; University of Colorado Boulder, Chemical and Biological Engineering Mavila, Sudheendran; University of Colorado, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering Wang, Chen; University of Colorado Boulder, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering Kontour, Taylor; University of Colorado Boulder, Chemical and Biological Engineering Lim, Chern-Hooi; University of Colorado Boulder, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering McBride, Matthew; University of Colorado Boulder, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering Musgrave, Charles; University of Colorado, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering Shoemaker, Richard; University of Colorado, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry Bowman, Christopher; University of Colorado, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering Page 1 of 14 PleasePolymer do not Chemistryadjust margins Polymer Chemistry ARTICLE A User’s Guide to the Thiol-Thioester Exchange in Organic Media: Scope, Limitations, and Applications in Material Science P8u8jhReceived 00th January a a a a a 20xx, Brady T. Worrell, Sudheenran Mavila, Chen Wang, Taylor M. Kontour, Chern-Hooi Lim, Accepted 00th January 20xx Matthew K. McBride,a Charles B. Musgrave,a Richard Shoemaker,a Christopher N. Bowmana,b,c,d* DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x The exchange of thiolates and thiols has long been held as a nearly ideal reaction in dynamic covalent chemistry. The www.rsc.org/ ability for the reaction to proceed smoothly in neutral aqueous media has propelled its widespread use in biochemistry, however, far fewer applications and studies have been directed towards its use in material science which primarily is performed in organic media. -

Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution (EAS) & Other Reactions Of

Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution (EAS) & Other Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Chapter 18 Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution • Additions across benzene rings are unusual because of the stability imparted by aromaticity. • Reactions that keep the aromatic ring intact are favored. • The characteristic reaction of benzene is electrophilic aromatic substitution—a hydrogen atom is replaced by an electrophile. Common EAS Reactions Halogenation • In halogenation, benzene reacts with Cl2 or Br2 in the presence of a Lewis acid catalyst, such as FeCl3 or FeBr3, to give the aryl halides chlorobenzene or bromobenzene, respectively. • Analogous reactions with I2 and F2 are not synthetically useful because I2 is too unreactive and F2 reacts too violently. • Mechanism of chlorination of benzene General Mechanism of Substitution • Regardless of the electrophile used, all electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions occur by the same two-step mechanism: 1. Addition of the electrophile E+ to form a resonance-stabilized carbocation. 2. Deprotonation with base. Resonance-Stabilized Aromatic Carbocation • The first step in electrophilic aromatic substitution forms a carbocation, for which three resonance structures can be drawn. • To help keep track of the location of the positive charge: Energy Diagram for Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Nitration and Sulfonation • Nitration and sulfonation introduce two different functional groups into the aromatic ring. • Nitration is especially useful because the nitro group can be reduced to an NH2 group. • Mechanisms of Electrophile Formation for Nitration and Sulfonation Reduction of Nitro Benzenes • A nitro group (NO2) that has been introduced on a benzene ring by nitration with strong acid can readily be reduced to an amino group (NH2) under a variety of conditions.