The Politburo's Predicament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Data Supplement

China Data Supplement October 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 29 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 36 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR................................................................................................................ 54 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR....................................................................................................................... 61 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 66 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

The Coming Show Trial of General Xu Caihou

Lawyers, Guns and Money: The Coming Show Trial of General Xu Caihou James Mulvenon On 30 June 2014, the Chinese Communist Party expelled former Politburo member and Central Military Commission vice-chair Xu Caihou for corruption following a three-month investigation. His case was transferred from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection to the military justice system for possible criminal prosecution, making him the highest- ranking military officer to be prosecuted since the founding of the PRC in 1949. His primary crime involved “trading offices for bribes,” and reportedly was uncovered during the investigation of General Gu Junshan. This article examines the Xu case, and assesses its implications for Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign and the military. Introduction On 30 June 2014, the Chinese Communist Party expelled former Politburo member and Central Military Commission vice-chair Xu Caihou for corruption following a three- month investigation. Xu, 70, joined the CMC in 1999 as director of the General Political Department and served as vice-chairman from 2004 to 2013. His case was transferred from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection to the military justice system for possible criminal prosecution, making him the highest-ranking military officer to be prosecuted since the founding of the PRC in 1949. His primary crime involved “trading offices for bribes,” which was reportedly uncovered during the investigation of disgraced former General Logistics Department deputy Gu Junshan (see CLM 37).1 This article examines the Xu case, and assesses its implications for Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign and the military. Xu was born in 1943 in Liaoning, and joined the PLA in 1963. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

28. Rights Defense and New Citizen's Movement

JOBNAME: EE10 Biddulph PAGE: 1 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Fri May 10 14:09:18 2019 28. Rights defense and new citizen’s movement Teng Biao 28.1 THE RISE OF THE RIGHTS DEFENSE MOVEMENT The ‘Rights Defense Movement’ (weiquan yundong) emerged in the early 2000s as a new focus of the Chinese democracy movement, succeeding the Xidan Democracy Wall movement of the late 1970s and the Tiananmen Democracy movement of 1989. It is a social movement ‘involving all social strata throughout the country and covering every aspect of human rights’ (Feng Chongyi 2009, p. 151), one in which Chinese citizens assert their constitutional and legal rights through lawful means and within the legal framework of the country. As Benney (2013, p. 12) notes, the term ‘weiquan’is used by different people to refer to different things in different contexts. Although Chinese rights defense lawyers have played a key role in defining and providing leadership to this emerging weiquan movement (Carnes 2006; Pils 2016), numerous non-lawyer activists and organizations are also involved in it. The discourse and activities of ‘rights defense’ (weiquan) originated in the 1990s, when some citizens began using the law to defend consumer rights. The 1990s also saw the early development of rural anti-tax movements, labor rights campaigns, women’s rights campaigns and an environmental movement. However, in a narrow sense as well as from a historical perspective, the term weiquan movement only refers to the rights campaigns that emerged after the Sun Zhigang incident in 2003 (Zhu Han 2016, pp. 55, 60). The Sun Zhigang incident not only marks the beginning of the rights defense movement; it also can be seen as one of its few successes. -

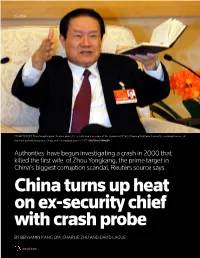

China Turns up Heat on Ex-Security Chief with Crash Probe

CHINA PRIME TARGET: Zhou Yongkang was head of domestic security and a member of the Communist Party Standing Politburo Committee, making him one of the most powerful people in China, until he stepped down in 2012. REUTERS/STRINGER Authorities have begun investigating a crash in 2000 that killed the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, the prime target in China’s biggest corruption scandal, Reuters source says. China turns up heat on ex-security chief with crash probe BY BENJAMIN KANG LIM, CHARLIE ZHU AND DAVID LAGUE SPECIAL REPORT 1 CHINA’S POWER STRUGGLE BEIJING/HONG KONG, SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 ittle is known about the exact circum- stances in which Wang Shuhua was Lkilled. What has been reported, in the Chinese media, is that she died in a road ac- cident sometime in 2000, shortly after she was divorced from her husband. And that at least one vehicle with a military license plate may have been involved in the crash. Fourteen years later, investigators are looking into her death. Their sudden inter- est has nothing to do with Wang herself. It has to do with the identity of her ex-hus- band – once one of China’s most powerful men and now the prime target in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. Investigators are probing the death of the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, China’s HUNTING TIGERS: President Xi Jinping has launched the biggest corruption crackdown since the retired security czar, a source with di- communists came to power in 1949, going after “tigers” or high-ranking officials as well as “flies”. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 2007 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–026 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Legacies

1 The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Legacies Vladimir Tismaneanu The revolutions of 1989 were, no matter how one judges their nature, a true world-historical event, in the Hegelian sense: they established a historical cleavage (only to some extent conventional) between the world before and after 89. During that year, what appeared to be an immutable, ostensibly indestructible system collapsed with breath-taking alacrity. And this happened not because of external blows (although external pressure did matter), as in the case of Nazi Germany, but as a consequence of the development of insuperable inner tensions. The Leninist systems were terminally sick, and the disease affected first and foremost their capacity for self-regeneration. After decades of toying with the ideas of intrasystemic reforms (“institutional amphibiousness”, as it were, to use X. L. Ding’s concept, as developed by Archie Brown in his writings on Gorbachev and Gorbachevism), it had become clear that communism did not have the resources for readjustment and that the solution lay not within but outside, and even against, the existing order.1 The importance of these revolutions cannot therefore be overestimated: they represent the triumph of civic dignity and political morality over ideological monism, bureaucratic cynicism and police dictatorship.2 Rooted in an individualistic concept of freedom, programmatically skeptical of all ideological blueprints for social engineering, these revolutions were, at least in their first stage, liberal and non-utopian.3 The fact that 1 See Archie Brown, Seven Years that Changed the World: Perestroika in Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 157-189. In this paper I elaborate upon and revisit the main ideas I put them forward in my introduction to Vladimir Tismaneanu, ed., The Revolutions of 1989 (London and New York: Routledge, 1999) as well as in my book Reinventing Politics: Eastern Europe from Stalin to Havel (New York: Free Press, 1992; revised and expanded paperback, with new afterword, Free Press, 1993). -

The Danger of Deconsolidation Roberto Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk Ronald F

July 2016, Volume 27, Number 3 $14.00 The Danger of Deconsolidation Roberto Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk Ronald F. Inglehart The Struggle Over Term Limits in Africa Brett L. Carter Janette Yarwood Filip Reyntjens 25 Years After the USSR: What’s Gone Wrong? Henry E. Hale Suisheng Zhao on Xi Jinping’s Maoist Revival Bojan Bugari¡c & Tom Ginsburg on Postcommunist Courts Clive H. Church & Adrian Vatter on Switzerland Daniel O’Maley on the Internet of Things Delegative Democracy Revisited Santiago Anria Catherine Conaghan Frances Hagopian Lindsay Mayka Juan Pablo Luna Alberto Vergara and Aaron Watanabe Zhao.NEW saved by BK on 1/5/16; 6,145 words, including notes; TXT created from NEW by PJC, 3/18/16; MP edits to TXT by PJC, 4/5/16 (6,615 words). AAS saved by BK on 4/7/16; FIN created from AAS by PJC, 4/25/16 (6,608 words). PGS created by BK on 5/10/16. XI JINPING’S MAOIST REVIVAL Suisheng Zhao Suisheng Zhao is professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver. He is executive director of the univer- sity’s Center for China-U.S. Cooperation and editor of the Journal of Contemporary China. When Xi Jinping became paramount leader of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 2012, some Chinese intellectuals with liberal lean- ings allowed themselves to hope that he would promote the cause of political reform. The most optimistic among them even thought that he might seek to limit the monopoly on power long claimed by the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). -

1992 a Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified 1992 A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France Citation: “A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France,” 1992, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Luo Guibo, "Wuchanjieji guojizhuyide guanghui dianfan: yi Mao Zedong he Yuan-Yue Kang-Fa" ("A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France"), in Mianhuai Mao Zedong (Remembering Mao Zedong), ed. Mianhuai Mao Zedong bianxiezhu (Beijing: Zhongyang Wenxian chubanshe, 1992) 286-299. Translated by Emily M. Hill http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/120359 Summary: Luo Guibo recounts China's involvement in the First Indochina War and its assistance to the Viet Minh. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation One Late in 1949, soon after the establishment of New China, Chairman Ho Chi Minh and the Central Committee of the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) wrote to Chairman Mao and the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), asking for Chinese assistance. In January 1950, Ho made a secret visit to Beijing to request Chinaʼs assistance in Vietnamʼs struggle against France. Following Hoʼs visit, the CCP Central Committee made the decision, authorized by Chairman Mao, to send me on a secret mission to Vietnam. I was formally appointed as the Liaison Representative of the CCP Central Committee to the ICP Central Committee. Comrade [Liu] Shaoqi personally composed a letter of introduction, which stated: ʻI hereby recommend to your office Comrade Luo Guibo, who has been a provincial Party secretary and commissar, as the Liaison Representative of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. -

610 Office” That I Witnessed by Hao Fengjun

EXHIBIT C The “610 Office” that I Witnessed By Hao Fengjun First of all, let me express my sincere gratitude to the invitation of Dr. Charles, the Vice President of the Human Rights Committee of the European Parliament. As a result I have this opportunity to briefly submit to the Committee what activities the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is currently engaged in through my personal experience. 1. The “610 Office” Truly Exists In 1994 I graduated from the Law Department in Nankai University in Tianjin. After graduation, I was assigned to work at Tianjin City Public Security Bureau. In October 2000, I was transferred to the “610 Office” under Tianjin Public Security Bureau. Since the Staffing Committee of the Tianjin City Party Committee had not granted the establishment of such a “610” organization at the time, the “610 Office” did not have any legal status. As a result, our personnel files were kept at the original work units. 1) Naming of the “610 Office” From 1999 to 2003, the “610 Office” was called the “Office to Deal with the Falun Gong Problem.” From 2003 to present, it is known as “The Office of Preventing and Handling Evil Cult Crimes (Bureau or Department)”. 2) Structure of the “610 Office” Nationwide Up until now, the CCP has never acknowledged the existence of the “610 Office” – an organization similar in nature to Nazi Germany’s Gestapo, which specializes in persecuting Falun Gong and other religious dissidents. Recently at an international press conference, the assistant to the CCP’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sheng Guofang, again publicly denied the existence of the “610 Office.” Many who do not know the true nature of the CCP may well believe the lie that is repeated a thousand times by the CCP. -

INSTITUTE for POLICY REFORM Working Paper Series

339.5 • 1575 w-81 INSTITUTE • FOR POLICY REFORM • • • • WAITE MEMORIAL BOOK COLLECTION DEPT. OF AG. AND APPUED ECONOMICS 1994 BUFORD AVE. - 232 COB UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA ST. PAUL, MN 55108 U.S.A. • Working Paper Series The objective of the Institute enhance the foundation for broad based • for Policy Reform is to economic growth in developing countries. Through its research, education and training activities the Institute encourages active participation in the dialogue on policy reform, focusing on changes that stimulate and sustain economic development. At the core of these activities is the search for creative ideas that can be used to design constitutional, institutional and policy reforms. Research fellows and policy practitioners are engaged by IPR to expand • the analytical core of the reform process. This includes all elements of comprehensive and customized reforms packages, recognizing cultural, political, economic and environmental elements as crucial dimensions of societies. 1400 16th Street, NW / Suite 350 Washington, DC 20036 (202)3450 • 339.5 • 1575 w-81 INSTITUTE 0 FOR POLICY REFORM • IPR81 Federalism, Chinese Style: The Political Basis for Economic Success in China Barry Weingastl, Yingyi Qian2 and Gabriella Montinola3 * • WAITE MEMORIAL BOOK COLLECTION DEPT. OF AG. AND APPUED ECONOMICS 1994 BUFORD AVE. - 232 COB UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA ST. PAUL MN 56108 USA 0 Working Paper Series • The objective of the Institute for Policy Reform is to enhance the foundation for broad based economic growth in developing countries. Through its research, education and training activities the Institute encourages active participation in the dialogue on policy reform, focusing on changes that stimulate and sustain economic development.