A Cross-Modal System Linking Primary Auditory and Visual Cortices: Evidence from Intrinsic Fmri Connectivity Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Sensory Processing: Looking at Children's Behavior Through the Lens of Sensory Processing

Understanding Sensory Processing: Looking at Children’s Behavior Through the Lens of Sensory Processing Communities of Practice in Autism September 24, 2009 Charlottesville, VA Dianne Koontz Lowman, Ed.D. Early Childhood Coordinator Region 5 T/TAC James Madison University MSC 9002 Harrisonburg, VA 22807 [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________ Dianne Koontz Lowman/[email protected]/2008 Page 1 Looking at Children’s Behavior Through the Lens of Sensory Processing Do you know a child like this? Travis is constantly moving, pushing, or chewing on things. The collar of his shirt and coat are always wet from chewing. When talking to people, he tends to push up against you. Or do you know another child? Sierra does not like to be hugged or kissed by anyone. She gets upset with other children bump up against her. She doesn’t like socks with a heel or toe seam or any tags on clothes. Why is Travis always chewing? Why doesn’t Sierra liked to be touched? Why do children react differently to things around them? These children have different ways of reacting to the things around them, to sensations. Over the years, different terms (such as sensory integration) have been used to describe how children deal with the information they receive through their senses. Currently, the term being used to describe children who have difficulty dealing with input from their senses is sensory processing disorder. _____________________________________________________________________ Sensory Processing Disorder -

The Visual System: Higher Visual Processing

The Visual System: Higher Visual Processing Primary visual cortex The primary visual cortex is located in the occipital cortex. It receives visual information exclusively from the contralateral hemifield, which is topographically represented and wherein the fovea is granted an extended representation. Like most cortical areas, primary visual cortex consists of six layers. It also contains, however, a prominent stripe of white matter in its layer 4 - the stripe of Gennari - consisting of the myelinated axons of the lateral geniculate nucleus neurons. For this reason, the primary visual cortex is also referred to as the striate cortex. The LGN projections to the primary visual cortex are segregated. The axons of the cells from the magnocellular layers terminate principally within sublamina 4Ca, and those from the parvocellular layers terminate principally within sublamina 4Cb. Ocular dominance columns The inputs from the two eyes also are segregated within layer 4 of primary visual cortex and form alternating ocular dominance columns. Alternating ocular dominance columns can be visualized with autoradiography after injecting radiolabeled amino acids into one eye that are transported transynaptically from the retina. Although the neurons in layer 4 are monocular, neurons in the other layers of the same column combine signals from the two eyes, but their activation has the same ocular preference. Bringing together the inputs from the two eyes at the level of the striate cortex provide a basis for stereopsis, the sensation of depth perception provided by binocular disparity, i.e., when an image falls on non-corresponding parts of the two retinas. Some neurons respond to disparities beyond the plane of fixation (far cells), while others respond to disparities in front of the plane of the fixation (near cells). -

Visual Stimulation Activities for Infants and Toddlers

National Institute for the Mentally Handicapped VISUAL STIMULATION ACTIVITIES FOR INFANTS AND TODDLERS A GUIDE TO PARENTS AND CAREGIVERS DR. AMAR Jyoihi PERShA Ms. K.R.NAWVi National Institute for the Mentally Handicapped (Ministryof Social Justice & Empowerment, Government of India) Manovikasnagar, Secunderabad - 500 009, Andhra Pradesh, INDIA. Grams : MANOVIKAS Phone : 040-27751741 Fax :040-27750198 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.nimhindia.org VISUAL STIMULATION ACTIVITIES FOR INFANTS AND TODDLERS Authors : Dr. Amar Jyothi Persha, Ms. K.R. Nawvi Copyright 2004 National Institute for the Mentally Handicapped Secunderabad - 500 009. All rights Reserved. ISBN 81 89001 02 7 Designing Ramana Chepuri, Ramesh Chepuri, Ramaswamy, Secunderabad - 500 003. Ph : 040-55762484 Printed by : Sree Ramana Process Pvt. Ltd., Secunderabad - 500 003. Ph : 040-27811750 ,&ii1iti iiiificti icçiIii FP-1T1 (i1 1TfTftrr Icl1,'T NATIONALINSTITUTE FOR THE Dr.L. GOVINDA RAO MENTALLYHANDICAPPED irector (Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India) FOREWORD This book is an outcome of the project titled "Development of stimulation activities for visually impaired infants and toddlers". Studies show that there are six lakh children born with visual problem each year, among them almost 80% have a residual visual capacity. The visual system gives us a variety of information about the environment, which is necessary for learning and acquiring skills for daily living. Vision is the sense that reveals the mystery of the world to the child. The eyes are the outgrowth of the brain and they parallel the development and growth of the brain in the first few months of life. Visual system matures rapidly as the brain does in these early years of life. -

Olfaction Modulates Ambiguous Visual Motion Perception

OPEN Smelling directions: Olfaction modulates SUBJECT AREAS: ambiguous visual motion perception HUMAN BEHAVIOUR Shenbing Kuang & Tao Zhang PERCEPTION MOTION State Key Laboratory of Brain and Cognitive Science, Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China. OLFACTORY CORTEX Senses of smells are often accompanied by simultaneous visual sensations. Previous studies have Received documented enhanced olfactory performance with concurrent presence of congruent color- or shape- 27 February 2014 related visual cues, and facilitated visual object perception when congruent smells are simultaneously present. These visual object-olfaction interactions suggest the existences of couplings between the olfactory Accepted pathway and the visual ventral processing stream. However, it is not known if olfaction can modulate visual 3 July 2014 motion perception, a function that is related to the visual dorsal stream. We tested this possibility by examining the influence of olfactory cues on the perceptions of ambiguous visual motion signals. We Published showed that, after introducing an association between motion directions and olfactory cues, olfaction could 23 July 2014 indeed bias ambiguous visual motion perceptions. Our result that olfaction modulates visual motion processing adds to the current knowledge of cross-modal interactions and implies a possible functional linkage between the olfactory system and the visual dorsal pathway. Correspondence and requests for materials n our daily life, we are constantly exposed to multiple sensory inputs from different sensory modalities of should be addressed to varying reliability. Yet we could effortless integrate these parallel sensory signals and maintain a unified T.Z. (taozhang@psych. I perception that allows us to interact with the external world. -

Anatomy and Physiology of the Afferent Visual System

Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 102 (3rd series) Neuro-ophthalmology C. Kennard and R.J. Leigh, Editors # 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved Chapter 1 Anatomy and physiology of the afferent visual system SASHANK PRASAD 1* AND STEVEN L. GALETTA 2 1Division of Neuro-ophthalmology, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Womens Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA 2Neuro-ophthalmology Division, Department of Neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA INTRODUCTION light without distortion (Maurice, 1970). The tear–air interface and cornea contribute more to the focusing Visual processing poses an enormous computational of light than the lens does; unlike the lens, however, the challenge for the brain, which has evolved highly focusing power of the cornea is fixed. The ciliary mus- organized and efficient neural systems to meet these cles dynamically adjust the shape of the lens in order demands. In primates, approximately 55% of the cortex to focus light optimally from varying distances upon is specialized for visual processing (compared to 3% for the retina (accommodation). The total amount of light auditory processing and 11% for somatosensory pro- reaching the retina is controlled by regulation of the cessing) (Felleman and Van Essen, 1991). Over the past pupil aperture. Ultimately, the visual image becomes several decades there has been an explosion in scientific projected upside-down and backwards on to the retina understanding of these complex pathways and net- (Fishman, 1973). works. Detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the visual The majority of the blood supply to structures of the system, in combination with skilled examination, allows eye arrives via the ophthalmic artery, which is the first precise localization of neuropathological processes. -

Rapid Evolution of the Visual System: a Cellular Assay of the Retina and Dorsal Lateral Geniculate Nucleus of the Spanish Wildcat and the Domestic Cat

The Journal of Neuroscience, January 1993, 13(l): 208-229 Rapid Evolution of the Visual System: A Cellular Assay of the Retina and Dorsal Lateral Geniculate Nucleus of the Spanish Wildcat and the Domestic Cat Robert W. Williams,’ Carmen Cavada,2 and Fernando Reinoso-Suhrez* ‘Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, College of Medicine, University of Tennessee, Memphis, Tennessee 38163 and *Departamento de Morfologia, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Aut6noma de Madrid, 28029 Madrid, Spain The large Spanish wildcat, Fe/is silvestris tartessia, has re- and important topic, it has been difficult to study the process tained features of the Pleistocene ancestor of the modern of brain evolution in any detail. Our approach has been to domestic cat, F. catus. To gauge the direction and magnitude identify a pair of closely related living species,one from a highly of short-term evolutionary change in this lineage, we have conservative branch that has retained near identity with the compared the retina, the optic nerve, and the dorsal lateral ancestral species,and the other from a derived branch that has geniculate nucleus (LGN) of Spanish wildcats and their do- undergone rapid evolutionary change. The recent recognition mestic relatives. Retinas of the two species have the same that evolution and speciationcan occur in short bursts separated area. However, densities of cone photoreceptors are higher by long interludes of stasisprovides a sound theoretical basis in wildcat-over 100% higher in the area centralis-where- for a search for such pairs (Schindewolf, 1950; Eldredge and as rod densities are as high, or higher, in the domestic lin- Gould, 1972; Stanley, 1979; Gould and Eldredge, 1986). -

Mapping out the Olfactory Design Space for Novel Interactions

1 SMELL SPACE: Mapping out the Olfactory Design Space for 2 Novel Interactions 3 4 SCHI Lab, School of Engineering and Informatics, University of Sussex, UK 5 EMANUELA MAGGIONI, 6 ROBERT COBDEN, SCHI Lab, School of Engineering and Informatics, University of Sussex, UK 7 DMITRIJS DMITRENKO, SCHI Lab, School of Engineering and Informatics, University of Sussex, UK 8 KASPER HORNBÆK, Department of Computer Science, University of Copenhagen, Denmark 9 MARIANNA OBRIST, SCHI Lab, School of Engineering and Informatics, University of Sussex, UK 10 The human sense of smell is powerful. However, the way we use smell as interaction modality in HCI is 11 limited. We lack a common reference point to guide designers’ choices when using smell. Here, we map out 12 an olfactory design space to provide designers with such guidance. We identified four key design features: (i) 13 chemical, (ii) emotional, (iii) spatial, and (iv) temporal. Each feature defines a building block for smell-based 14 interaction design and is grounded in a review of the relevant scientific literature. We then demonstrate 15 the design opportunities in three application cases. Each application (i.e. one desktop, two virtual reality 16 implementations) highlights the design choices alongside the implementation and evaluation possibilities in 17 using smell. We conclude by discussing how identifying those design features facilitates a healthy growth of 18 this research domain and contributes to an intermediate-level knowledge space. Finally, we discuss further 19 challenges the HCI community needs to tackle. 20 CCS Concepts: • Human-centered computing → Interaction techniques; Empirical studies in HCI. 21 Additional Key Words and Phrases: Smell; Olfactory Design Space; Chemical Sense; Scent-based Interaction 22 Design; Odour Interfaces; Smell-based Applications; Novel Interactions 23 ACM Reference Format: 24 Emanuela Maggioni, Robert Cobden, Dmitrijs Dmitrenko, Kasper Hornbæk, and Marianna Obrist. -

Visual-Vestibular Coordination

Visual-Vestibular Coordination The visual and vestibular systems share an inseparable neurological and functional connection. Together they provide the foundation for skillful and comfortable movement through space and time as well as for efficient intake of visual information for learning. Although vestibular functions and oculomotor control are typically addressed in sensory integration treatment, the efficient coordination of these systems is more recently being targeted in treatment for enhanced functional visual skills. Your therapist here at OTA The Koomar Center (OTA) may be talking to you about incorporating such focused activities within treatment sessions and within a home program. The vestibular system is often referred to as the movement or balance system. The receptors are located within the inner ear, and respond to gravity and detect motion and change of head position. They tell us where we are in relationship to gravity, if we are moving or at rest, and our speed and direction of movement. The vestibular system is a powerful integrator that interacts with all other sensory systems. It most noticeably impacts our posture, balance, muscle tone, and bilateral coordination. The visual system is more than just eyesight, or the ability to see clearly. It is also our ability to understand what we see. It is estimated that at least 75% of learning occurs through visual pathways. If an individual is experiencing any visual difficulties, learning will most likely be impacted. For efficient oculomotor function, complex integration of many sensory systems must occur. According to Josephine Moore, the vestibular system is like a tripod stand that holds a camera, in that it helps hold the head stable so that the eyes can focus on an object. -

Visual Illusions and Perception

Visual illusions and perception 2005 McGraw-Hill Yearbook of Science and Technology Donald D. Hoffman Department of Cognitive Science University of California, Irvine, 92697 To the casual observer visual illusions may appear to be mere curiosities, amusing tricks for the eye concocted by clever artists. But, to the serious student of perception, visual illusions reveal important secrets. Vision seems effortless: We simply open our eyes and see the world as it is. This apparent ease is itself an illusion. Tens of billions of neurons, and trillions of synapses, labor together in the simple act of opening our eyes and looking. Visual illusions, far from being mere parlor tricks, allow researchers to peer inside this complexity and discover what all these neurons are doing. What they reveal is surprising. Most of us assume that our vision is much like a camera, simply taking snapshots or movies, and providing an objective report of what is around us. Visual illusions, and the research that builds on them, reveal that vision does not report objective truth but instead weaves elaborate interpretations based on sophisticated detective work. Vision is more like Sherlock Holmes than movie cameras. Certainly the eye itself is a miniature camera, focusing an image on its retina at the back 1 of the eye. But this retina is composed of hundreds of millions of neurons performing sophisticated operations, and the signals they send to the brain engage a network of billions of neurons. This is where vision really takes place, and where the sophisticated detective work swiftly and expertly proceeds. So swiftly and so expertly that one can hardly be faulted for missing it. -

Effects of Visual and Proprioceptive Information in Visuo-Motor Calibration During a Closed-Loop Physical Reach Task in Immersive Virtual Environments

Effects of Visual and Proprioceptive Information in Visuo-Motor Calibration During a Closed-Loop Physical Reach Task in Immersive Virtual Environments Elham Ebrahimi∗, Bliss Altenhoffy, Leah Hartmany, J. Adam Jones∗, Sabarish V. Babu∗, Christopher C. Paganoy, Timothy A. Davis ∗ Abstract ception of depth in virtual reality, but only some of these factors have been well studied. There are still many that need further in- Research in visuo-motor coupling has shown that the matching of vestigation. Perception and neurology literature suggest that ac- visual and proprioceptive information is important for calibrating curate depth perception is a fundamental process that is necessary movement. Many state-of-the art virtual reality (VR) systems, com- for higher level perceptual and cognitive spatial processing, such monly known as immersive virtual environments (IVE), are created as shape, speed, and size perception [Landy et al. 1995]. In spite for training users in tasks that require accurate manual dexterity. of substantial efforts to create virtual environments that carefully Unfortunately, these systems can suffer from technical limitations replicate real world situations, many studies still demonstrate that that may force de-coupling of visual and proprioceptive informa- depth perception in VR is distorted [Witmer and Sadowski 1998; tion due to interference, latency, and tracking error. We present Messing and Durgin 2005; Richardson and Waller 2005; Willemsen an empirical evaluation of how visually distorted movements af- et al. 2009]. These kinds of distortions become problematic, espe- fects users’ reach to near field targets using a closed-loop physical cially when VR is used to train skills that are aimed to transfer to reach task in an IVE. -

7 Senses Street Day Bringing the Common Sense Back to Our Neighbourhoods

7 Senses Street Day Bringing the common sense back to our neighbourhoods Saturday, 16 November 2013 What are the 7 Senses? Most of us are familiar with the traditional five senses – sight, smell, taste, hearing, and touch. The two lesser known senses refer to our movement and balance (Vestibular) and our body position (Proprioception). This article gives an overview of each of the senses and how the sensory processing that occurs for us to interpret the world around us. Quick Definitions Sensory integration is the neurological process that organizes sensations from one's body and from the environment, and makes it possible to use the body to make adaptive responses within the environment. To do this, the brain must register, select, interpret, compare, and associate sensory information in a flexible, constantly-changing pattern. (A Jean Ayres, 1989) Sensory Integration is the adequate and processing of sensory stimuli in the central nervous system – the brain. It enables us interact with our environment appropriately. Sensory processing is the brain receiving, interpreting, and organizing input from all of the active senses at any given moment. For every single activity in daily life we need an optimal organization of incoming sensory information. If the incoming sensory information remains unorganized – e.g. the processing in the central nervous system is incorrect - an appropriate, goal orientated and planned reaction (behavior) relating to the stimuli is not possible. Sight Sight or vision is the capability of the eyes to focus and detect images of visible light and generate electrical nerve impulses for varying colours, hues, and brightness. -

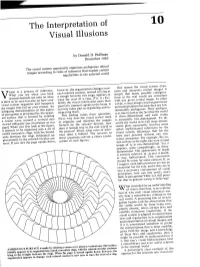

The Interpretation of Visual Illusions

The Interpretation of 10 Visual Illusions by Donald D. Hoffman December 1983 The visual system apparently organizes ambiguous retinal images according to rules of inference that exploit certain regularities in the external world ision is a process of inference. however, the organization changes: now One reason the visual system orga- What you see when you look each colored contour, instead of lying in nizes and interprets retinal images is V around depends not only on what a trough between two rings, appears to simply that many possible configura- is there to be seen but also on how your trace the crest of a ring. (Try it.) Evi- tions in the real world are consistent visual system organizes and interprets dently the visual system does more than with any given retinal image. In other the images that fall on your retinas. An passively transmit signals to the brain. It words, retinal images need organization intriguing demonstration of this aspect . actively takes part in organizing and in- and interpretation because they are fun- of perception is presented by the appar- terpreting them. damentally ambiguous. Their ambigui- ent surface that is formed by rotating This finding raises three questions. ty is due in part to the fact that the world a cosine wave around a vertical axis First, why does the visual system need is three-dimensional and each retina viewed obliquely [see illustration on this to organize and interpret the images is essentially two-dimensional. To de- page]. When you first look at the figure, formed on the retinas? Second, how scribe the world in its full three-dimen- it appears to be organized into a set of does it remain true to the real world in sional glory necessarily involves some raised concentric rings, with the bound- the process? Third, what rules of infer- rather sophisticated inferences by the aries between the rings delineated ap- ence does it follow? The answers to visual system, inferences that for the proximately by the colored circular con- these questions call for a closer exami- most part proceed without any con- tours.