Briefings on Nuclear Technology in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 1991-92

ANNUAL REPORT 1991-92 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ATOMIC ENERGY REGULATORY BOARD BOMBAY ATOMIC ENERGY REGULATORY BOARD Shri S.D. Soman ... Chairman Dr. R.D. Lele ... Member Consultant Physician and Director of Nuclear Medicine, Jaslok Hospital & Research Centre, Bombay. Dr. S.S. Ramaswamy ... Member Retd. Director General, Factory Advice Service & Labour Institute Bombay. Dr. A. Ciopalakrishnan ... Member Director, Central Mechanical Engineering Research Institute Durgapur S.Vasant Kumar ... Ex-officio Chairman, Member Safety Review Committee for Operating Plants (SARCOP), Bombay Dr. K.S. Parthasarathy ... Secretary Dy. Director, AERB Atomic Energy Regulatory Board, Vikram Sarabhai Bhavari, Anushakti Nagar, Bombay-400 094. ATOMIC ENERGY REGULATORY BOARD The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board was constituted on November 15. 1983 by the President of India by exercising the powers conferred by Section 27 of the Atomic Energy Act 1962 (33 of 1962) to cany out certain regulatory and safety functions under the Act The regulatory authority (Annexure-I) of AERB is derived from rules and notifications promulgated under the Atomic Energy Act 1962 and Environmental Protection Act 1986 The mission of the Beard is to ensure that the use of ionizing radiation and nuclear energy in India does not cause undue risk to health safety and the environment The Board consists of a full time Chairman, an ex-officio Member, three part time Members and a Secretary The bio-data of its members is given in Annexure-ll AERB is supported by th? Advisory Committees for Proiect Salety Review (ACPSRs one for the nuclear power projects and the other for heavy water projects) Ihe Safely Review Committee for Operating Plants (SARCOP) and Salety Review Committee for Applications ol Radiation (SARCARt The memberships of these committees are given in Annexure-lll The ACPSR recommends to the AERB. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR TH MONDAY, THE 14 AUGUST, 2017 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 38 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 39 TO 44 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 45 TO 51 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 52 TO 59 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 14.08.2017 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 14.08.2017 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-I) HON'BLE THE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE C. HARI SHANKAR FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. W.P.(C) 5873/2017 RESIDENTS WELFARE ASSOCIATION KUMAR SUSHOBHAN Vs. NORTH DMC & ORS FOR ADMISSION _______________ 2. FAO(OS) 84/2017 ASHOK KUMAR KATHURIA JITENDRA KUMAR SINGH CM APPL. 10929/2017 Vs. OM PRAKASH KATHURIA (THR CM APPL. 10930/2017 LEGAL HEIRS) & ORS CM APPL. 10931/2017 3. W.P.(C) 4860/2017 YASHPAL SINGH SAURABH KANSAL Vs. GOVT OF NCT OF DELHI AND ORS AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS ____________________________ 4. FAO(OS) 30/2017 PRAVEEN KUMAR SANJEEV RALLI,KUMAR DUSHYANT CM APPL. 3849/2017 Vs. KOTAK MAHINDRA BANK LTD & SINGH ORS 5. FAO(OS) 118/2017 PRADEEP MEHRA SAURABH PRAKASH & KUNAL Vs. BCH ELECTRIC LTD GOSAIN 6. W.P.(C) 3136/2017 OM PRAKASH SHREY CHATHLY CM APPL. 13667/2017 Vs. EAST DELHI MUNICIPAL CORPORATION 7. CM APPL. 27481/2017 AREEBA HASAN & ORS SANDEEP BAJAJ,R K TARUN AND CM APPL. 27482/2017 Vs. CENTRAL BOARD OF ASSO,ONKAR PRASAD,A K THAKUR CM APPL. -

01.03.2017 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST 1. Urgent Mentioning May Be Made Before Hon'ble DB-III at 10.30 A.M. 2. Hon'ble Ms. Justice

01.03.2017 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMNT OF JUDGMENTS ------------> 01 TO 03 REGULAR MATTERS -----------------------> 01 TO 224 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ---------> 01 TO 26 ADVANCE LIST --------------------------> 01 TO 73 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 74 TO 100 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 101 TO 115 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)--------> 116 TO 122 COMPANY -------------------------------> 123 TO 124 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY -------------------> 125 TO MEDIATION CAUSE LIST ------------------> 01 TO 02 THIRD SUPPLEMENTARY -------------------> - TO PRE-LOK ADALAT-------------------------> 1 TO 1 NOTES 1. Urgent mentioning may be made before Hon'ble DB-III at 10.30 A.M. 2. Hon'ble Ms. Justice Deepa Sharma will not be holding Court today. Dates will be given by the Court Master. Urgent mentioning be made before Court No.24. DELETIONS 1. CRL.A. 192/2017 listed before Hon'ble DB-V at item No.1 is deleted as the same is listed before Hon'ble VIII. 2. CRL.A. 536/2016 listed before Hon'ble DB-V at item No.6 is deleted as the same is fixed for 29.03.2017. 3. ITA 1025/2008, ITA 1084/2008 & ITA 1095/2008 listed before Hon'ble DB- VI at item Nos. 19, 20 & 21 respectively are deleted as the same are decided matters. 4. RFA 245/2017 listed before Hon'ble Ms. Justice Hima Kohli at item No.25 is deleted as the same is returned to Filing Counter. 5. CONT.CAS(C) 875/2009 listed before Hon'ble Mr. -

Cir201813367.Pdf

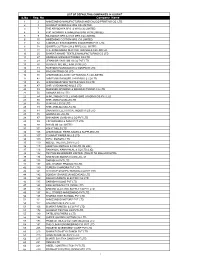

GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI DEPARTMENT OF TRAINING AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION MUNI MAYA RAM MARG, PITAM PURA, DELHI-88 [ROOM NO. 203, NG/E-II Branch] www.tte.delhigovt.nic.in Email: [email protected] 011-27321014 NOTICE Subject:-Scrutiny of applications for the post of Instructor on part time basis in the Government Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) under the aegis of DTTE, Government of NCT Delhi for the Academic Year 2018-19 up to 31st July 2019. A list of ineligible candidates who had applied for the post of Instructor on part time basis has been uploaded on the website of the Department. Any candidate, who has been rendered ineligible and has objection about his/her rejection/ineligibility or whose name does not find place in any of the lists(eligible/ineligible), may submit his/her representation with documentary evidence on or before 17.09.2018 upto 05.00 PM in the chamber of Administrative Officer (NG/E-II Branch), Room No. 206, Department of Training & Technical Education, Muni Maya Ram Marg, Pitampura, New Delhi-110088. The Department will hold interview of following eligible candidates for the post of Instructors on part time hourly basis as per interview schedule given here under: INTERVIEW SCHEDULE REG. NO. NAME OF APPLICANT FATHER'S NAME (SH.) DOB POST/TRADE DATE & TIME (SH./SMT.) OF INTERVIEW PT-0694 PARUL JAIN B B JAIN 04.01.1993 PT-0865 RENU MAAN RAM RATTAN MAAN 10.04.1990 ARCH. ASST PT2266 RENU MAAN RAM RATTAN MAAN 10.04.1990 PT-2057 SANJAY KUMAR SATYAVEER SINGH 02.03.1993 PT0010 AKHILESH -

E-Newsletter Volume 1 Issue 1 November 2019

Volume-1 Issue-1 For Internal Private Circulation only FROM CHAIRMAN’S DESK Dr. U. Kamachi Mudali Chairman IIChE-MRC Indian Institute Of Chemical Engineers is a confluence of streams of professionals from academia, research institute and industry. It was founded by Dr. Hira Lal Roy before Indian Independence in order to cluster stalwarts in Chemical Engineering from various professions to support the chemical industries as well as Institutes by providing a forum for interaction and joint endeavors. IIChE- MRC conducts and supports many events through out the year and feels it prudent to share its achievements with all members. Hence, IIChE-MRC decided to publish this quarterly e- newsletter for the benefit of all members from academia, research institute, industry and student chapters to gain acquaintance with current events, technical articles on Industry and upcoming events of IIChE-MRC. I hope that this e-newsletter proves beneficial to the chemical engineering as well as allied sciences readers and encourage them to take up joint ventures with immense participation towards the Nation building. Dr. U. Kamachi Mudali IIChEMRC Executive Committee Dr. U. Kamachi Mudali, Hon. Chairman Mr. Rajesh Jain Member Dr Anita Kumari Hon. Vice Chairperson Mr. Ravindra Joshi Member Dr. Alpana Mahapatra Member Dr. Bibhash Chakravorty Hon. Secretary Dr. T.L. Prasad Member Mr. Dhawal Saxena Hon. Jt Secretary Mr. V.Y.Sane Member Mr. Mahendra Patel Hon. Treasurer Mr. Joy Shah Member Mr. Shreedhar .M. Chitanvis Member Dr. Aparna M. Tamaskar Member INDIAN INSTITUTE OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERS Mumbai Regional Centre B-18, Vardhman Complex, Gr Floor, Opp Home Town & 247 Park, LBS Marg, Vikhroli (West), Mumbai - 400 083 1 November 2019 IICHE MRC E-NEWSLETTER 1 Volume-1 Issue-1 INDEX From Chairman’s Desk / IICHEMRC Executive Committee Index / Editor’s Corner / Disclaimer Recent Events / Forthcoming Events • Workshop on Solid Waste Management on 24/09/2019 at IITB I by NAE, IITB, IIChE & IEA. -

Nuclear Power Business Executive V P L&T Ltd

11TH NUCLEAR ENERGY CONCLAVE Steering Committee Dr S Banerjee Shri Anil Razdan Dr. R. B. Grover Chairman, Nuclear Energy President, IEF & Member, AEC & Group, IEF, Chancellor, Homi Former Secretary,Power Former Vice Chancellor Bhabha National Institute Homi Bhabha & Former Chairman, AEC & National Institute Secretary, DAE Ms. Minu Singh Shri V.P. Singh Shri P.P. Yadav Shri Anil Parab M.D., Nuvia India Former ED, BHEL ED (Nuclear Power Business Executive V P L&T Ltd. Development), BHEL Dr Harsh Mahajan Shri Amarjit Singh, MBE Shri S.C. Chetal Shri S.M. Mahajan Director, Mahjan Imaging Secretary General, IEF Former Director, IGCAR & Convener, Nuclear Group, Mission Director, AUSC Project IEF, Former ED, BHEL & Consultant (Power Sector) Organiser India Energy Forum: The Forum is a unique, independent, not-for-profit, research organization and represents energy sector as a whole. It is manned by highly qualified and experienced energy professionals committed to evolving a national energy policy. The Forum's mission is the development of a sustainable and competitive energy sector, promoting a favourable regulatory framework, establishing standards for reliable and safety, ensuring an equitable deal for consumers, producers and the utilities, encouraging efficient and eco-friendly development and use of energy and developing new and better technologies to meet the growing energy needs of the society. Its membership includes all the key players of the sector including BHEL, NTPC, NHPC, Power Grid Corporation, Power Finance Corporation, Reliance Energy, Alstom and over 100 highly respected energy experts. It works closely with various chambers and trade associates including Bombay Chamber, Bengal Chamber, Madras Chamber, PHD Chamber, Observer Research Foundation, IRADE, INWEA,Indian Coal Forum, and FIPI. -

Nuclear Energy in India's Energy Security Matrix

Nuclear Energy in India’s Energy Security Matrix: An Appraisal 2 of 55 About the Author Maj Gen AK Chaturvedi, AVSM, VSM was commissioned in Corps of Engineers (Bengal Sappers) during December 1974 and after a distinguished career of 38 years, both within Engineers and the staff, retired in July 2012. He is an alumnus of the College of Military Engineers, Pune; Indian Institute of Technology, Madras; College of Defence Management, Secunderabad; and National Defence College, New Delhi. Post retirement, he is pursuing PhD on ‘India’s Energy Security: 2030’. He is a prolific writer, who has also been quite active in lecture circuit on national security issues. His areas of interests are energy, water and other elements of ‘National Security’. He is based at Lucknow. http://www.vifindia.org © Vivekananda International Foundation Nuclear Energy in India’s Energy Security Matrix: An Appraisal 3 of 55 Abstract Energy is essential for the economic growth of a nation. India, which is in the lower half of the countries as far as the energy consumption per capita is concerned, needs to leap frog from its present position to upper half, commensurate with its growing economic stature, by adopting an approach, where all available sources need to be optimally used in a coordinated manner, to bridge the demand supply gap. A new road map is needed to address the energy security issue in short, medium and long term. Solution should be sustainable, environment friendly and affordable. Nuclear energy, a relatively clean energy, has an advantage that the blueprint for its growth, which was made over half a century earlier, is still valid and though sputtering at times, but is moving steadily as envisaged. -

11. 2"'DST/SERC School on "Isotope Tracer Techniques for Water Resources Development and Management' 23 Dr Bhabhawasmuchmorethanthat

11. 2"'DST/SERC school on "Isotope tracer techniques for water resources development and management' 23 Dr Bhabhawasmuchmorethanthat. Hewasa Recognitionisan importantmotivatingfactor;so brilliantscientistand an outstandingscience are opportunityand rewarding professional administrator.But most of all, he was a avenues.TheScientificAdvisoryCommitteeto pioneeringvisionary, who understoodthe theCabinet- headedbyourPrincipalScientific importanceofindigenousscientificresearchfor Adviser, Dr Chidambaram- has been self-reliantdevelopment. consideringhowto optimisethebenefitstothe Visionarieslike Bhabha have shaped the countryfromitsscientificresearchinstitutions.It shouldalsotacklethechallengeofrecruitingthe scientifictemperofourcountry.Indiaistodayat bestscientifictaientintoourresearchinstitutions the forefrontof the KnowledgeRevolution- whichdrivestheNewEconomy.Forthis,weowe andretainingthemthere.Wehavetonurturean environment,whichencouragestheinnovative a hugedebt to the excellenceofour scientific andtechnicalpersonnel. spiritandwelcomescreativeideas. Muchofthistalentfindsitswayabroad.Fromthe In thiscontext,it is hearteningtosee thatso SiliconValleyto Microsoft,frombiochemistryto manyyoung studentsparticipatedinthe DAE robotics - expatriateIndian scientistsand essaycontest.Theyareourfuturescientistsand. engineers are present in every corporate engineers.Theywill becomeourambassadors, organisationandineveryfieldofresearch. carrying the message of science based development to various partsourcountry. India's atomic energy programmestartedherein -

S.No Reg. No Company Name 1 2 AHMEDABAD MANUFACTURING and CALICO PRINTING CO

LIST OF DEFAULTING COMPANIES IN GUJRAT S.No Reg. No Company_Name 1 2 AHMEDABAD MANUFACTURING AND CALICO PRINTING CO. LTD. 2 3 GUJARAT GINNING & MFG CO.LIMITED. 3 7 THE ARYODAYA SPG & WVG.CO.LIMITED. 4 8 40817HCHOWK & AHMEDABAD MFG CO.LIMITED. 5 9 RAJNAGAR SPG & WVG MFG.CO.LIMITED. 6 10 HMEDABAD COTTON MFG. CO.LIMITED. 7 12 12DISPLAY STATUSSTEEL INDUSTRIES PVT. LTD. 8 18 ISHWER COTTON G.N.& PRES.CO.LIMITED. 9 22 THE AHMEDABAD NEW COTTON MILLS CO.LIMITED. 10 25 BHARAT KHAND TEXTILE MANUFACTURING CO LTD 11 27 HIMABHAI MANUFACTURING CO LTD 12 29 JEHANGIR VAKIL MILLS CO PVT LTD 13 30 GUJARAT OIL MILL & MFG CO LTD 14 31 RUSTOMJI MANGALDAS & COMPANY LTD 15 34 FINE KNITTING CO LTD 16 40 AHMEDABAD LAXMI COTTON MILLS CO.LIMITED. 17 42 AHMEDABAD KAISER-I-HIND MILLS CO LTD 18 45 AHMEDABAD NEW TEXTILE MILS CO LTD 19 47 SHRI VIVEKANAND MILLS LTD 20 49 MARSDEN SPINNING & MANUFACTURING CO LTD 21 50 ASHOKA MILLS LTD. 22 54 AHMEDABAD CYCLE & MOTORS TRADING CO PVT LTD 23 68 SHRI AMRUTA MILLS LTD 24 78 VIJAY MILLS CO LTD 25 79 SHRI ARBUDA MILLS LTD. 26 81 DHARWAR ELECTRICAL INDUSTRIES LTD 27 85 ANANTA MILLS LTD 28 87 BHIKABHAI JIVABHAI & CO PVT LTD 29 89 J R VAKHARIA & SONS PVT LTD 30 99 BIHARI MILLS LIMITED 31 101 ROHIT MILLS LTD 32 106 AHMEDABAD FIBRE-SALES & SUPPLIES LTD 33 107 GUJARAT PAPER MILLS LTD 34 109 IDEAL MOTORS LTD 35 110 MODEL THEATRES PVT LTD 36 115 HIMATLAL MOTILAL & CO LTD.(IN LIQ.) 37 116 RAMANLAL KANAIYALAL & CO LTD.(LIQ). -

E-Newsletter Volume 2 Issue 1 April 2020

Volume-2 Issue-1 For Internal Private Circulation only FROM CHAIRMAN’S DESK Dr. U. Kamachi Mudali Chairman IIChE-MRC Around the world, all eyes are on the spread of the COVID-19. The pandemic is challenging families, health care systems, and governments. The pandemic is also challenging our organization and staff in unprecedented ways. The challenge, however, is prompting necessary action, while avoiding over-reaction. India has stood up to the coronavirus crisis as Industry, R&D, academia and media are supporting government to kick out the menace. People are following key advices on hand washing, coughing etiquette, not touching face, physical distance and staying at home. With this type of support and discipline, I have no doubt that together we will win soon. Indian Institute of Chemical Engineers (IIChE) is the premier professional organization furthering the development of chemical, petrochemical and allied industries with respect to R&D, design and engineering, educational programmes and consultancy. It also provides a platform for interacting with other disciplines of science and engineering. Apart from its tremendous academic and professional value, IIChE happens to be the most opportune ground for our members and other participants to network with fellow professionals, which is undeniably an important prerequisite for professional growth today. IIChE-MRC, being the largest among regional centres of IIChE, continues to conduct and support many events throughout the year. It also prudent to share achievements with members through this triannual E-Newsletter for the benefit of members. There has been inspiring feedback on last issue of the E-Newsletter across the board which was circulated among many regional centers, HQ, social networks, former EC members etc. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR TH FRIDAY, THE 27 MARCH, 2015 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 45 2. SPECIAL BENCH (APPLT. SIDE) 46 TO 54 3. COMPANY JURISDICTION 55 TO 57 4. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 58 TO 71 5. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 72 TO 90 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 27.03.2015 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 27.03.2015 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE RAJIV SAHAI ENDLAW AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS ____________________________ 1. LPA 37/2015 GOVERNMENT OF NCT OF DELHI YEESHU JAIN,ARUN BIRBAL CM APPL. 1344/2015 THR SECRETARY (LAND AND CM APPL. 1345/2015 BUILDING DEPARTMENT) Vs. AFTAB AHMED AND ANR CONNECTED MATTERS (ANMM) __________________________ 2. LPA 25/2014 UNION PUBLIC SERVICE NARESH KAUSHIK,K L CM APPL. 678/2014 COMMISSION MANHAS,RESPONDENT IN PERSON CM APPL. 679/2014 Vs. SH K L MANHAS CM APPL. 680/2014 CM APPL. 19102/2014 3. LPA 26/2014 UNION PUBLIC SERVICE NARESH KAUSHIK CM APPL. 681/2014 COMMISSION CM APPL. 682/2014 Vs. SAHADEVA SINGH CM APPL. 683/2014 4. LPA 27/2014 UNION PUBLIC SERVICE NARESH KAUSHIK,SUBHIKSH CM APPL. 690/2014 COMMISSION VASUDEV CM APPL. 691/2014 Vs. SH G S SANDHU CM APPL. 692/2014 5. LPA 29/2014 UNION PUBLIC SERVICE NARESH KAUSHIK CM APPL. 706/2014 COMMISSION CM APPL. 707/2014 Vs. SH TARSEM LAL CM APPL. -

Federal Register/Vol. 63, No. 223/Thursday, November 19, 1998

64322 Federal Register / Vol. 63, No. 223 / Thursday, November 19, 1998 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Regulatory Policy Division, Bureau of missile technology reasons have been Export Administration, Department of made subject to this sanction policy Bureau of Export Administration Commerce, P.O. Box 273, Washington, because of their significance for nuclear DC 20044. Express mail address: explosive purposes and for delivery of 15 CFR Parts 742 and 744 Sharron Cook, Regulatory Policy nuclear devices. [Docket No. 98±1019261±8261±01] Division, Bureau of Export To supplement the sanctions of Administration, Department of RIN 0694±AB73 § 742.16, this rule adds certain Indian Commerce, 14th and Pennsylvania and Pakistani government, parastatal, India and Pakistan Sanctions and Avenue, NW, Room 2705, Washington, and private entities determined to be Other Measures DC 20230. involved in nuclear or missile activities FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: to the Entity List in Supplement No. 4 AGENCY: Bureau of Export Eileen M. Albanese, Director, Office of to part 744. License requirements for Administration, Commerce. Exporter Services, Bureau of Export these entities are set forth in the newly ACTION: Interim rule. Administration, Telephone: (202) 482± added § 744.11. Exports and reexports of SUMMARY: In accordance with section 0436. all items subject to the EAR to listed 102(b) of the Arms Export Control Act, SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: government, parastatal, and private entities require a license. A license is President Clinton reported to the Background Congress on May 13th with regard to also required if you know that the India and May 30th with regard to In accordance with section 102(b) of ultimate consignee or end-user is a Pakistan his determinations that those the Arms Export Control Act, President listed government, parastatal, or private non-nuclear weapon states had each Clinton reported to the Congress on May Indian or Pakistani entity, and the item detonated a nuclear explosive device.