Comparing Practices of US Volleyball Systems Against a Global Model for Integrated Development of Mass and High Performance Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VOLLEYBALL Table of Contents (Click on an Item to Jump Directly to That Section) Page IMPORTANT DATES and DEADLINES

VOLLEYBALL Table of Contents (click on an item to jump directly to that section) Page IMPORTANT DATES AND DEADLINES ....................................................................................................... 3 STATE MEET SITES AND DATES .................................................................................................................. 3 STATE TOURNAMENT BRACKET ................................................................................................................ 4 RULE REVISIONS .............................................................................................................................................. 5 SOUTH DAKOTA CHANGES ........................................................................................................................... 5 SOUTH DAKOTA MODIFICATIONS ............................................................................................................. 6 GENERAL INFORMATION Classification and Alignments ....................................................................................................................... 6 On-Line Schedules and Rosters ...................................................................................................................... 6 Match Limitation ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Length of Sets & Matches/Match Format ................................................................................................... -

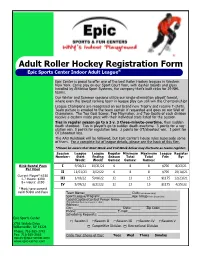

Inline Hockey Registration Form

Adult Roller Hockey Registration Form Epic Sports Center Indoor Adult League® Epic Center is proud to offer one of the best Roller Hockey leagues in Western New York. Come play on our Sport Court floor, with dasher boards and glass installed by Athletica Sport Systems, the company that’s built rinks for 29 NHL teams. Our Winter and Summer sessions utilize our single-elimination playoff format, where even the lowest ranking team in league play can still win the Championship! League Champions are recognized on our brand new Trophy and receive T-shirts. Team picture is emailed to the team captain if requested and goes on our Wall of Champions. The Top Goal Scorer, Top Playmaker, and Top Goalie of each division receive a custom made prize with their individual stats listed for the session. Ties in regular season go to a 3 v. 3 three-minute-overtime, then sudden death shootout. Ties in playoffs go to sudden death overtime. 3 points for a reg- ulation win. 0 points for regulation loss. 2 points for OT/shootout win. 1 point for OT/shootout loss. The AAU Rulebook will be followed, but Epic Center’s house rules supersede some of them. For a complete list of league details, please see the back of this flier. *Please be aware that Start Week and End Week below may fluctuate as teams register. Session League League Regular Minimum Maximum League Register Number: Start Ending Season Total Total Fee: By: Week: Week: Games: Games: Games: Rink Rental Fees I 9/06/21 10/31/21 6 8 8 $700 8/23/21 Per Hour II 11/01/21 1/02/22 6 8 8 $700 10/18/21 Current Player*:$150 -

ADULT SPORTS FAQ's 1. What Are the Age Requirements for Participation in Adult Sports Programs?

ADULT SPORTS FAQ’s 1. What are the age requirements for participation in Adult Sports programs? Volleyball participants must be at least 16 years of age during the season in order to be eligible. Basketball, Dodgeball, Flag-Football, and Softball participants must be at least 18 years of age during the season in order to be eligible. The age difference in adult sports programs is due to the potential level of physical contact during league play. 2. Are uniforms required in team sports participation? Team uniforms are not required for our volleyball or softball leagues. Basketball, Dodgeball, and Flag-Football teams, however, must wear same color shirts with permanent numbers placed on the back. All teams provide their own equipment. Game balls are provided only in the softball program. 3. Why are the fees so high for the adult leagues? League fees are used to pay for scorekeepers, staffing, facility maintenance and equipment. Awards are also given to the top two teams in each division. Compared to other communities, our fees are still considerably affordable. YOUTH SPORTS FAQ’s 1. What are the age requirements for participation in Youth Sports programs? Children learn at various stages and must learn all the skills necessary before advancing to a higher level. It is recommended that participants sign up according to the grade or age limit assigned to a particular program. The Instructor may then recommend a participant to be moved to a more advanced level if the participant is physically and cognitively ready. 2. My child will meet the proper age limit in a couple of months. -

A/B Grade Level: 9-10-11-12 773800 This Semester-Long Course Includes In

HEALTH AND PHYSICAL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT TEAM SPORTS: A/B Grade Level: 9-10-11-12 773800 This semester-long course includes instruction in two or three activity units per quarter. Each unit offers opportunities for student growth in health enhancing fitness activities, movement skills and concepts of personal and social responsibility. Students will apply the knowledge of components and principles in health- and skill-related fitness when creating a personal fitness plan. Units of study in team sports may include hockey, flag football, ultimate Frisbee, team handball, soccer, basketball, softball, volleyball, Tchoukball or other team sports chosen by the instructor. Unlimited repeats for subject credit VOLLEYBALL: A/B Grade Level: 9-10-11-12 775131/775132 This course is designed for volleyball players of all ability levels to develop necessary volleyball skills to participate for life. Zero previous volleyball experience is required. Throughout the semester students will participate in volleyball related fitness activities in addition to the gameplay and skill development. The first quarter of the course will emphasize skill development, with a moderate amount of time for game play. The second quarter of the course will emphasize game play, strategies, and tactics with a moderate amount of time for skill development. The course requires excellent sportsmanship as we want all classmates to feel encouraged to participate no matter their skill level and enjoy their class time. Unlimited repeats for subject credit NET/RACKET SPORTS: A/B Grade Level: 9-10-11-12 773700 This course is designed for students of all ability levels to develop necessary racket sport skills to participate for life. -

Wilson Ball Cleaning Recommendations

What chemicals can clean our game balls without altering performance? Our primary recommendation is to follow CDC, state and local guidelines for health and safety. The following widely accepted definitions are relevant to composite leather, PU leather, and leather game ball care (CDC reference): There are several different methods for sanitizing and disinfecting composite leather, PU leather, and leather game product. Each customer should utilize the method that fits their health and safety protocols and the playing environment and timing needs. Simple Game Ball Cleaning Method To clean the ball, players may wish to use dish soap and water. While this practice may be likened to hand washing, note that all soap residue must be rinsed away and that drying time on each ball product may vary. An example cleaning regimen with soap and water includes: 1. Add 1 tablespoon of mild dish soap into a 1-gallon container. 2. Fill bucket with warm water, until a soapy mixture is formed. 3. Wet a first towel with the solution, wring out excess water, and gently wipe down entire product surface for at least 30 seconds. 4. Re-wet towel with plain warm water, wring out excess water, and wipe off excess soap from ball surface. 5. Rub a second, dry towel on the surface to wipe and dry off. 6. Let product air out overnight. Quick Turn Leather Game Ball Cleaning Method To clean the ball with faster turnaround times, we reference the following recommendations. The CDC released a list (referred to as ‘List N’) of effective disinfectants for disabling SARS-CoV-2 (i.e., the virus that causes Covid-19 disease) on hard, nonporous surfaces. -

CHALLENGE WINTER 2019 5 Photo Courtesy of Wheelchair Sports Federation

THE GAME OF BASKETBALL, ON WHEELS Page 6 SITTING VOLLEYBALL Page 16 A PUBLICATION OF DISABLED SPORTS USA WINTER 2019 VOLUME 24 | NUMBER 3 3S80 Sports Knee The athlete’s first choice. The robust yet lightweight 3S80 Sports Knee dynamically responds to a changing running pace. From recreational runners to Paralympic athletes, and everyone in between, the 3S80 can help you reach your goals. Scout Bassett, Track and Field Paralympian 11/19 ©2019 Ottobock HealthCare, LP, All rights reserved. 11/19 ©2019 Ottobock HealthCare, LP, www.ottobockus.com Quality for life Contents PERSPECTIVE 5 Glenn Merry Executive Director THE GAME OF 6 BASKETBALL, ON WHEELS WARFIGHTER SPORTS: 12 MIKE KACER WARFIGHTER SPORTS 14 CALENDAR SITTING VOLLEYBALL: 16 A TEAM SPORT WITH A SUPER FAST PACE E-TEAM MEMBER 18 THOMAS WILSON’S LIFE TAKES A 360 SPIN CHAPTER LISTING 20 Find Your Local Chapter CHAPTER EVENTS 22 Upcoming Adaptive Sports Opportunities MARKETPLACE 39 Product Showcase © 2019 by Disabled Sports USA, Inc. All rights reserved. Articles may not be reprinted in part or in whole without written permission from DSUSA. Cover photo of Team USA Wheelchair Basketball Player Matt Scott. Cover photo by 6 Wheelchair Sports Federation. 16CHALLENGE 18 31 4 WINTER 2019 PERSPECTIVE 2020 is upon us, which means the Summer Paralympic Games will be taking place in Tokyo, Japan, beginning in August. For this issue, we are featuring two sports that will be a part of those games. We hope the articles introduce you to the respective sports and get you excited for the games when they come around. -

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veteran Monthly Assistance Allowance for Disabled Veterans Training in Paralympic and Olympic Sports Program (VMAA) In partnership with the United States Olympic Committee and other Olympic and Paralympic entities within the United States, VA supports eligible service and non-service-connected military Veterans in their efforts to represent Team USA at the Paralympic Games, Olympic Games and other international sport competitions. The VA Office of National Veterans Sports Programs & Special Events provides a monthly assistance allowance for disabled Veterans training in Paralympic sports, as well as certain disabled Veterans selected for or competing with the national Olympic Team, as authorized by 38 U.S.C. 322(d) and Section 703 of the Veterans’ Benefits Improvement Act of 2008. Through the program, VA will pay a monthly allowance to a Veteran with either a service-connected or non-service-connected disability if the Veteran meets the minimum military standards or higher (i.e. Emerging Athlete or National Team) in his or her respective Paralympic sport at a recognized competition. In addition to making the VMAA standard, an athlete must also be nationally or internationally classified by his or her respective Paralympic sport federation as eligible for Paralympic competition. VA will also pay a monthly allowance to a Veteran with a service-connected disability rated 30 percent or greater by VA who is selected for a national Olympic Team for any month in which the Veteran is competing in any event sanctioned by the National Governing Bodies of the Olympic Sport in the United State, in accordance with P.L. -

U.S. Olympic Training Center, Colorado Springs, Colo

U.S. Olympic Training Center – Colorado Springs, Colo. Fact Sheet The U.S. Olympic Complex in Colorado Springs is the headquarters for the U.S. Olympic Committee administration and the U.S. Olympic Training Center programs. Training Center Overview Currently, there are nine National Governing Bodies that have their national sport headquarters on the Complex, as well as U.S. Paralympics. Those that are currently on the Complex include: USA Badminton, USA Boxing, USA Cycling, USA Judo, USA Shooting, USA Swimming, USA Taekwondo, USA Triathlon, USA Weightlifting. Additionally, there are 12 other National Governing Bodies that have their headquarters located in the Colorado Springs area. They are as follows: USA Archery, USA Basketball, USA Fencing, USA Field Hockey, U.S. Figure Skating, USA Hockey, USA Racquetball, USA Table Tennis, USA Team Handball, USA Volleyball, USA Water Polo and USA Wrestling. Additionally, two international sports federations are located nearby in Colorado Springs. The U.S. Olympic Complex, former home of ENT Air Force Base and headquarters of the North American Defense Command, officially became the USOC administrative headquarters in July 1978. In October 1996 and April 1997, the USOC officially dedicated and opened its new $23.8 million, Phase II facilities, which include: a state-of-the-art sports medicine and sport science center and an athlete center, which houses a dining hall and two residence halls. The USOC is able to provide housing, dining, recreational facilities and other services for up to 557 coaches and athletes at one time on the Complex. Facilities Aquatics Center The Aquatics Center is 45,000 square feet and contains a 50x25-meter swimming pool, two meters deep at the ends and three meters deep in the center. -

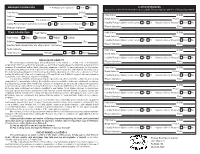

Liability Release Option

MANAGER INFORMATION Is manager also a player? Yes No PLAYER INFORMATION See section to the left for information about Liability Release Options and Use of Images Agreement Print Name: D.O.B: Print Name: D.O.B: Address: City: Zip: Email Address: Phone: Phone: Email Address: Liability Release Option (select one): A B Agree to Use of Images? Yes No Liability Release Option (select one;see below): A B Agree to Use of Images? Yes No Player Signature: Date: Manager Signature: Date: TEAM INFORMATION Team Name: Print Name: D.O.B: Email Address: Phone: Select One: Bags Volleyball Fistball Softball Liability Release Option (select one): A B Agree to Use of Images? Yes No Address: City: Zip: Player Signature: Date: Has this team played under any other name? List names: Team requests: Print Name: D.O.B: Team Sponsor: Amount: Cash CC Check# Email Address: Phone: Liability Release Option (select one): A B Agree to Use of Images? Yes No RELEASE OF LIABILITY Player Signature: Date: The undersigned acknowledges that participation is not related to, arising from, or incidental to employment with Pioneer Bowl for any purpose, and further hereby agree(s) to indemnify, defend and hold harmless Pioneer Bowl (without limit), damages, expenses or liability for personal injuries, bodily injuries, Print Name: D.O.B: death, property damage or theft of personal belongings sustained by the undersigned: 1) arising out of the undersigned’s participation in the team sport activities; 2) arising out of the acts or omissions of third- Email Address: Phone: parties; 3) arising out of the acts or omissions of Pioneer Bowl; and 4) without regard to whose negligence Liability Release Option (select one): A B Agree to Use of Images? Yes No caused the costs, damages, expenses or liability. -

Here Are Some Easy Starter Tips for Teaching the Game of Tchoukball to Your PE Students

Here are some easy starter tips for teaching the game of Tchoukball to your PE students • Don’t tell them they can score at either rebounder. At first tell your teams they can only score at the opposite end. This will get them used to moving the ball up and down the court. You can add the both frame rule down the road. • Remember the rules of 3: 3 sec to hold the ball, only three steps, and when you are attacking both ends you cannot throw at the same rebounder after 3 trys. • When there is a change of possession make sure there is a “reset” by the new team. A reset is done by touching the ball to the floor with both hands on the ball. This can be done anywhere; it does not have to be at the goal line. • Don’t allow students to guard, intercept or even get in the way of a student who is trying to throw or catch a ball. No blocking out, screening, standing in the way of the rebounder is allowed. The team without the ball actually must make a concentrated effort to stay out of the way of the offensive team. • Once the ball leaves the hand of the team trying to score, they must now make sure they are not interfering with the other team trying to catch their ball. Any interference here is a foul and loss of possession/no score. • Small sided games are the best….3-5 players on a team. You can have a third team rotate in after a score. -

Colorado Sports and Events Center Presentation

Colorado Sports and Events Center Presentation Submitted to: Colorado Economic Development Commission September 20, 2018 ROBSON ARENA - COLORADO COLLEGE WEIDNER STADIUM - SWITCHBACKS FC Colorado Sports and Events Center Table of Contents Introduction … Presentation … Business Plan … Sports Authority … Compliance with Exhibit B … Net New Out of State Visitors Analyses … Commencement of Substantial Work … Letters of Support … Colorado Sports and Events Center INTRODUCTION Colorado Sports and Event Center The City of Colorado Springs is moving forward with the fourth City for Champions project; the Colorado Sports and Event Center. Comprised of two facilities, these will be state of the art, multi-purpose venues designed to host professional, Olympic and amateur sporting events as well as entertainment and cultural events. The outdoor downtown stadium will become the permanent home of the Colorado Springs Switchbacks while the indoor event center will serve as the new home of the Colorado College ice hockey team. Partnering and providing private financial funding in the venture are Colorado College, the Colorado Springs Switchbacks and Weidner Apartment Homes. Downtown Stadium The downtown stadium will be located at the CityGate property bordered by Cimarron to the North, Moreno to the South, Sierra Madre to the West and Sahwatch to the east. The facility will be a mixed-use development which will feature a rectangular field of play and will serve as the permanent home of the Colorado Springs Switchbacks. The stadium, containing 10,000 spectator seats for sporting events, will be a multi-use facility that can accommodate a wide variety of sporting and entertainment events. Capacity for concert events will be 20,000. -

Rugby Sevens

DISCOVER YOUR GOLD: RUGBY SEVENS What is Rugby Sevens? Rugby Sevens is played under similar laws to rugby union and is played on a full size pitch by teams of seven players rather than fifteen. The game is shorter in duration, with each half lasting seven minutes during the pool stages of a tournament, and increasing to ten for the final. Because Rugby Sevens is played on a full size pitch, players need to be able to cover a lot of ground during a match. This means that participants need to be incredibly fit and have plenty of speed, skill and stamina. The basics of Rugby - running, passing, tackling and decision-making - are key components of Rugby Sevens, as are creating space and keeping possession of the ball. Rugby Sevens made its eagerly awaited debut in the Summer Olympics in Rio 2016 with the GB Women’s team finishing fourth and the GB Men’s team winning a silver medal. Who are we looking for? Perhaps you are a sprinter or play another team sport such as netball, basketball or volleyball – Rugby Sevens suits athletes who are quick, have good hand-eye coordination and enjoy being part of a team. The key sign-up criteria for #DiscoverYour Gold is outlined below: What if I am younger or older than what you are looking for? If you are 15 or 16 years old then we would encourage you to join your local rugby sevens club. You can find out all about your nearest club by visiting http://www.englandrugby.com/my-rugby/find-rugby/ If you are over 24 years old but have competed internationally in your sport and believe that you have the ability to transfer quickly into the sport of rugby sevens then please contact us on … Campaign graduate … Deborah’s story … Name: Deborah Fleming DOB/ Age: 26y Hometown: Penzance, Cornwall Campaign: Power2Podium 2011 Previous sport: National level sprinter and regional netball player Career Highlight: Represented England in the Rugby World Sevens Series in 2016/17 Twitter: @DeborahF91 .