B O Sto N a Frican a M Erican

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews the Public Historian, Vol

Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews The Public Historian, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Spring 2003), pp. 80-87 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the National Council on Public History Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/tph.2003.25.2.80 . Accessed: 23/02/2012 10:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and National Council on Public History are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Public Historian. http://www.jstor.org 80 n THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews The American public increasingly receives its history from images. Thus it is incumbent upon public historians to understand the strategies by which images and artifacts convey history in exhibits and to encourage a conver- sation about language and methodology among the diverse cultural work- ers who create, use, and review these productions. The purpose of The Public Historian’s exhibit review section is to discuss issues of historical exposition, presentation, and understanding through exhibits mounted in the United States and abroad. Our aim is to provide an ongoing assess- ment of the public’s interest in history while examining exhibits designed to influence or deepen their understanding. -

From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, Or the Legacy of Ishmael

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Faculty Publications Department of English 2012 From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, or The Legacy of Ishmael Elizabeth J. West Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation West, Elizabeth J., "From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, or The Legacy of Ishmael" (2012). English Faculty Publications. 15. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_facpub/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, or The Legacy of Ishmael” Dr. Elizabeth J. West Dept. of English—Georgia State Univ. Nov. 2010 “Call me Ishmael,” Herman Melville’s elusive narrator instructs readers. The central voice in the lengthy saga called Moby Dick, he is a crewman aboard the Pequod. This Ishmael reveals little about himself, and he does not seem altogether at home. As the narrative unfolds, this enigmatic Ishmael seems increasingly out of sorts in the world aboard the Pequod. He finds himself at sea working with and dependent on fellow seamen, who are for the most part, strange and frightening and unreadable to him. -

The Tarring and Feathering of Thomas Paul Smith: Common Schools, Revolutionary Memory, and the Crisis of Black Citizenship in Antebellum Boston

The Tarring and Feathering of Thomas Paul Smith: Common Schools, Revolutionary Memory, and the Crisis of Black Citizenship in Antebellum Boston hilary j. moss N 7 May 1851, Thomas Paul Smith, a twenty-four-year- O old black Bostonian, closed the door of his used clothing shop and set out for home. His journey took him from the city’s center to its westerly edge, where tightly packed tene- ments pressed against the banks of the Charles River. As Smith strolled along Second Street, “some half-dozen” men grabbed, bound, and gagged him before he could cry out. They “beat and bruised” him and covered his mouth with a “plaster made of tar and other substances.” Before night’s end, Smith would be bat- tered so severely that, according to one witness, his antagonists must have wanted to kill him. Smith apparently reached the same conclusion. As the hands of the clock neared midnight, he broke free of his captors and sprinted down Second Street shouting “murder!”1 The author appreciates the generous insights of Jacqueline Jones, Jane Kamensky, James Brewer Stewart, Benjamin Irvin, Jeffrey Ferguson, David Wills, Jack Dougherty, Elizabeth Bouvier, J. M. Opal, Lindsay Silver, Emily Straus, Mitch Kachun, Robert Gross, Shane White, her colleagues in the departments of History and Black Studies at Amherst College, and the anonymous reviewers and editors of the NEQ. She is also grateful to Amherst College, Brandeis University, the Spencer Foundation, and the Rose and Irving Crown Family for financial support. 1Commonwealth of Massachusetts vs. Julian McCrea, Benjamin F. Roberts, and William J. -

The Attucks Theater September 4, 2020 | Source: Theater/ Words by Penny Neef

Spotlight: The Attucks Theater September 4, 2020 | Source: http://spotlightnews.press/index.php/2020/09/04/spotlight-the-attucks- theater/ Words by Penny Neef. Images as credited. Feature image by Mike Penello. In the early 20th century, segregation was a fact of life for African Americans in the South. It became a matter of law in 1926. In 1919, a group of African Americans from Norfolk and Portsmouth met to develop a cultural/business center in Norfolk where the black community “could be treated with dignity and respect.” The “Twin Cities Amusement Corporation” envisioned something like a modern-day town center. The businessmen obtained funding from black owned financial institutions in Hampton Roads. Twin Cities designed and built a movie theater/ retail/ office complex at the corner of Church Street and Virginia Beach Boulevard in Norfolk. Photo courtesy of the family of Harvey Johnson The businessmen chose 25-year-old architect Harvey Johnson to design a 600-seat “state of the art” theater with balconies and an orchestra pit. The Attucks Theatre is the only surviving theater in the United States that was designed, financed and built by African Americans. The Attucks was named after Crispus Attucks, a stevedore of African and Native American descent. He was the first patriot killed in the Revolutionary War at the Boston Massacre of 1770. The theatre featured a stage curtain with a dramatic depiction of the death of Crispus Attucks. Photo by Scott Wertz. The Attucks was an immediate success. It was known as the “Apollo Theatre of the South.” Legendary performers Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn, Nat King Cole, and B.B. -

16 043539 Bindex.Qxp 10/10/06 8:49 AM Page 176

16_043539 bindex.qxp 10/10/06 8:49 AM Page 176 176 B Boston Public Library, 29–30 Babysitters, 165–166 Boston Public Market, 87 Index Back Bay sights and attrac- Boston Symphony Index See also Accommoda- tions, 68–72 Orchestra, 127 tions and Restaurant Bank of America Pavilion, Boston Tea Party, 43–44 Boston Tea Party Reenact- indexes, below. 126, 130 The Bar at the Ritz-Carlton, ment, 161–162 114, 118 Brattle, William, House A Barbara Krakow Gallery, (Cambridge), 62 Abiel Smith School, 49 78–79 Brattle Book Shop, 80 Abodeon, 85 Barnes & Noble, 79–80 Brattle Street (Cambridge), Access America, 167 Barneys New York, 83 62 Accommodations, 134–146. Bars, 118–119 Brattle Theatre (Cambridge), See also Accommodations best, 114 126, 129 Index gay and lesbian, 120 Bridge (Public Garden), 92 best bets, 134 sports, 122 The Bristol, 121 toll-free numbers and Bartholdi, Frédéric Brookline Booksmith, 80 websites, 175 Auguste, 70 Brooks Brothers, 83 Acorn Street, 49 Beacon Hill, 4 Bulfinch, Charles, 7, 9, 40, African Americans, 7 sights and attractions, 47, 52, 63, 67, 173 Black Nativity, 162 46–49 Bunker Hill Monument, 59 Museum of Afro-Ameri- Berklee Performance Center, Burleigh House (Cambridge), can History, 49 130 62 African Meeting House, 49 Berk’s Shoes (Cambridge), Burrage Mansion, 71 Agganis Arena, 130 83 Bus travel, 164, 165 Air travel, 163 Big Dig, 174 airline numbers and Black Ink, 85 C websites, 174–175 Black Nativity, 162 Calliope (Cambridge), 81 Alcott, Louisa May, 48, 149 The Black Rose, 122 Cambridge Common, 61 Alpha Gallery, 78 Blackstone -

Black Citizenship, Black Sovereignty: the Haitian Emigration Movement and Black American Politics, 1804-1865

Black Citizenship, Black Sovereignty: The Haitian Emigration Movement and Black American Politics, 1804-1865 Alexander Campbell History Honors Thesis April 19, 2010 Advisor: Françoise Hamlin 2 Table of Contents Timeline 5 Introduction 7 Chapter I: Race, Nation, and Emigration in the Atlantic World 17 Chapter II: The Beginnings of Black Emigration to Haiti 35 Chapter III: Black Nationalism and Black Abolitionism in Antebellum America 55 Chapter IV: The Return to Emigration and the Prospect of Citizenship 75 Epilogue 97 Bibliography 103 3 4 Timeline 1791 Slave rebellion begins Haitian Revolution 1831 Nat Turner rebellion, Virginia 1804 Independent Republic of Haiti declared, Radical abolitionist paper The Liberator with Jean-Jacques Dessalines as President begins publication 1805 First Constitution of Haiti Written 1836 U.S. Congress passes “gag rule,” blocking petitions against slavery 1806 Dessalines Assassinated; Haiti divided into Kingdom of Haiti in the North, Republic of 1838 Haitian recognition brought to U.S. House Haiti in the South. of Representatives, fails 1808 United States Congress abolishes U.S. 1843 Jean-Pierre Boyer deposed in coup, political Atlantic slave trade chaos follows in Haiti 1811 Paul Cuffe makes first voyage to Africa 1846 Liberia, colony of American Colonization Society, granted independence 1816 American Colonization Society founded 1847 General Faustin Soulouque gains power in 1817 Paul Cuffe dies Haiti, provides stability 1818 Prince Saunders tours U.S. with his 1850 Fugitive Slave Act passes U.S. Congress published book about Haiti Jean-Pierre Boyer becomes President of 1854 Martin Delany holds National Emigration Republic of Haiti Convention Mutiny of the Holkar 1855 James T. -

HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 587 by Matheny a RESOLUTION to Honor Frederick Douglass for His Legacy of Advancing and Protecting Civi

HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 587 By Matheny A RESOLUTION to honor Frederick Douglass for his legacy of advancing and protecting civil rights. WHEREAS, Frederick Douglass was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey near Easton, Maryland, in February of 1818, and lived the first twenty years of his life as a slave before escaping to freedom in 1838 through the Underground Railroad; and; WHEREAS, with the assistance of abolitionists, he resettled in New Bedford, Massachusetts and changed his name to avoid recapture by fugitive slave bounty hunters; he thus began a new life as Frederick Douglass and worked tirelessly to help other slaves flee north through the Underground Railroad; and WHEREAS, Frederick Douglass, who had no formal education and taught himself to read and write, would go on to become one of the Nation’s leading abolitionists; his seminal autobiographical work, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, explained with unsurpassed eloquence and detail how slavery corrupts the human spirit and robs both master and slave of their freedom; and WHEREAS, Frederick Douglass was not only prominent as an uncompromising abolitionist, but he also defended women’s rights; and WHEREAS, Frederick Douglass, through his writings, lectures, speeches, activism, and relationship with President Abraham Lincoln helped the Nation summon the will to accept civil war as the price to abolish slavery and emancipate millions from bondage; and WHEREAS, Frederick Douglass was a strong advocate for African American service in the Civil -

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council © Essays compiled by Alicestyne Turley, Director Underground Railroad Research Institute University of Louisville, Department of Pan African Studies for the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, Frankfort, KY February 2010 Series Sponsors: Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Kentucky Historical Society Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council Underground Railroad Research Institute Kentucky State Parks Centre College Georgetown College Lincoln Memorial University University of Louisville Department of Pan African Studies Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission The Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission (KALBC) was established by executive order in 2004 to organize and coordinate the state's commemorative activities in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln. Its mission is to ensure that Lincoln's Kentucky story is an essential part of the national celebration, emphasizing Kentucky's contribution to his thoughts and ideals. The Commission also serves as coordinator of statewide efforts to convey Lincoln's Kentucky story and his legacy of freedom, democracy, and equal opportunity for all. Kentucky African American Heritage Commission [Enabling legislation KRS. 171.800] It is the mission of the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission to identify and promote awareness of significant African American history and influence upon the history and culture of Kentucky and to support and encourage the preservation of Kentucky African American heritage and historic sites. -

LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

1 LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD ewis Hayden died in Boston on Sunday morning April 7, 1889. L His passing was front- page news in the New York Times as well as in the Boston Globe, Boston Herald and Boston Evening Transcript. Leading nineteenth century reformers attended the funeral including Frederick Douglass, and women’s rights champion Lucy Stone. The Governor of Massachusetts, Mayor of Boston, and Secretary of the Commonwealth felt it important to participate. Hayden’s was a life of real signi cance — but few people know of him today. A historical marker at his Beacon Hill home tells part of the story: “A Meeting Place of Abolitionists and a Station on the Underground Railroad.” Hayden is often described as a “man of action.” An escaped slave, he stood at the center of a struggle for dignity and equal rights in nine- Celebrate teenth century Boston. His story remains an inspiration to those who Black Historytake the time to learn about Month it. Please join the Town of Framingham for a special exhibtion and visit the Framingham Public Library for events as well as displays of books and resources celebrating the history and accomplishments of African Americans. LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Presented by the Commonwealth Museum A Division of William Francis Galvin, Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Opens Friday February 10 Nevins Hall, Framingham Town Hall Guided Tour by Commonwealth Museum Director and Curator Stephen Kenney Tuesday February 21, 12:00 pm This traveling exhibit, on loan from the Commonwealth Museum will be on display through the month of February. -

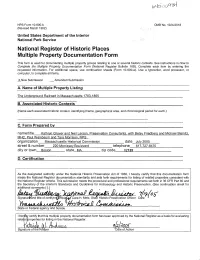

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPSForm10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Revised March 1992) . ^ ;- j> United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. _X_New Submission _ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing__________________________________ The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts 1783-1865______________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) C. Form Prepared by_________________________________________ name/title Kathrvn Grover and Neil Larson. Preservation Consultants, with Betsy Friedberg and Michael Steinitz. MHC. Paul Weinbaum and Tara Morrison. NFS organization Massachusetts Historical Commission________ date July 2005 street & number 220 Morhssey Boulevard________ telephone 617-727-8470_____________ city or town Boston____ state MA______ zip code 02125___________________________ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National -

The Freedmen'sbureau's Judicial

Louisiana Law Review Volume 79 Number 1 The Fourteenth Amendment: 150 Years Later Article 6 A Symposium of the Louisiana Law Review Fall 2018 1-24-2019 “To This Tribunal the Freedman Has Turned”: The Freedmen’sBureau’s Judicial Powers and the Origins of the FourteenthAmendment Hon. Bernice B. Donald Pablo J. Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Hon. Bernice B. Donald and Pablo J. Davis, “To This Tribunal the Freedman Has Turned”: The Freedmen’sBureau’s Judicial Powers and the Origins of the FourteenthAmendment, 79 La. L. Rev. (2019) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol79/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “To This Tribunal the Freedman Has Turned”: The Freedmen’s Bureau’s Judicial Powers and the Origins of the Fourteenth Amendment Hon. Bernice B. Donald* and Pablo J. Davis** TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................................................... 2 I. Wartime Genesis of the Bureau ....................................................... 5 A. Forerunners ................................................................................ 6 B. Creation of the Bureau ............................................................... 9 II. The Bureau’s Original Judicial Powers .......................................... 13 A. Judicial Powers Under the First Freedmen’s Bureau Act ............................................................................... 13 B. Cession and Reassertion of Jurisdiction .................................. 18 III. The Battle Over the Second Freedmen’s Bureau Act .................... 20 A. Challenges to the Bureau’s Judicial Powers ............................ 20 B. -

The Long American Revolution: Black Abolitionists and Their

Gordon S. Barker. Fugitive Slaves and the Unfinished American Revolution: Eight Cases, 1848-1856. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2013. 232 pp. $45.00, paper, ISBN 978-0-7864-6987-1. Reviewed by Emily Margolis Published on H-Law (January, 2014) Commissioned by Craig Scott U.S. historians tend to mark the end of the their Revolution was the war against slavery and American Revolution as George Bancroft did, in their quest was to create a “more perfect union.” the early 1780s when military action with the Therefore, he claims their Revolution ended--at British ceased (upon either the surrender of Corn‐ the very earliest date--with the ratification of the wallis at Yorktown in 1781 or the Treaty of Paris Thirteenth Amendment. in 1783). As Gordon Barker rightly points out, in Using black and white abolitionist lectures, the 1980s, American and Atlantic social historians correspondence, annual reports, newspapers, di‐ began to produce a new body of scholarship that aries, and memoirs, as well as Northern and challenged this periodization as they found ordi‐ Southern newspapers, fugitive slave trials, and nary men, women, and African Americans em‐ lawyers’ papers, Barker employs a sociopolitical ploying the principles of the Declaration of Inde‐ approach to illustrate African Americans’ contin‐ pendence in their battle to gain freedom from dif‐ ued battle against the tyranny of slavery. To show ferent types of tyranny long after the end of the their continued Revolution, he centers his book eighteenth century. In fact, some argue that the on the late 1840s and 1850s and chronicles eight battle, for these groups, continues today.