Mq-42936-Publisher Version (Open Access)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music and Environmentalism in Iceland

This is a repository copy of Music and Environmentalism in Iceland. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/98624/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Dibben, N. orcid.org/0000-0002-9250-5035 (2017) Music and Environmentalism in Iceland. In: Holt, F. and Kärjä, A-V., (eds.) Oxford Handbook of Popular Music in the Nordic Countries. Oxford University Press , Oxford . ISBN 9780190603908 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 8 Music and Environmentalism in Iceland Nicola Dibben How much would we accept for a mountain? Two billion? Twenty billion?i At the end of the trailer for the television eco-documentary Draumalandi! (2007), an interviewee questions the monetary value placed on landscape. The question encapsulates ongoing controversies over ownership, valuation and use of the natural environment in the Nordic region and beyond. It presents an implicit opposition between, on the one hand, economic valuation of the natural environment, epitomised by natural capital accounting (measurement and incorporation into markets of natural resources and ecosystems), and on the other hand, the idea that nature is, and should remain, in the realm of the “beyond-human”. -

Björk's Biophilia Björk's Whole Career Has Been a Quest for the Ultimate Fusion of the Organic and the Electronic

Björk's Biophilia Björk's whole career has been a quest for the ultimate fusion of the organic and the electronic. With her new project Biophilia – part live show, part album, part iPad app – she might just have got there Michael Cragg The Guardian, Saturday 28 May 2011 larger | smaller Iceland's singer Bjork performs during the Rock en Seine music festival, 26 August 2007 in Saint-Cloud Photograph: Afp/AFP/Getty Images For Björk, technology, nature and art have always been inextricably linked. "In Iceland, everything revolves around nature, 24 hours a day," she told Oor magazine in 1997. "Earthquakes, snowstorms, rain, ice, volcanic eruptions, geysers … very elementary and uncontrollable. But on the other hand, Iceland is incredibly modern; everything is hi- tech." The Modern Things, a track from 1995's Post, playfully posits the theory that technology has always existed, waiting in mountains for humans to catch up. In fact, Björk has always seemed like an artist who's been waiting for technology to catch up with her. Finally, it seems to have done so. When Apple announced details of its iPad early last year, it acted as a catalyst for what would become Biophilia, Björk's seventh and most elaborate album, the title of which means "love of life or living systems". Along with a conventional album release, complete with music videos – at least one of which has been directed by Eternal Sunshine's Michel Gondry – Biophilia will also be released as an "app album" and premiered as a multimedia live extravaganza at MIF. Biophilia for iPad will include around 10 separate apps, all housed within one "mother" app. -

2019 Tcc Jfteixeira.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ INSTITUTO DE CULTURA E ARTE CURSO DESIGN-MODA JOHANN FREITAS TEIXEIRA BJÖRK E SEU CORAÇÃO PARTIDO: UMA ANÁLISE DAS RELAÇÕES ENTRE FIGURINO E DESIGN GRÁFICO A PARTIR DO ENCARTE DO ÁLBUM VULNICURA FORTALEZA 2019 JOHANN FREITAS TEIXEIRA BJÖRK E SEU CORAÇÃO PARTIDO: UMA ANÁLISE DAS RELAÇÕES ENTRE FIGURINO E DESIGN GRÁFICO A PARTIR DO ENCARTE DO ÁLBUM VULNICURA MonografiA ApresEntAda como conclusão de Curso Em DEsign-Moda do Instituto de Cultura E ArtE – ICA da Universidade FEderal do CeArá – UFC, como requisito parciAl para obtEnção de Título de Bacharel em DEsign-Moda. OriEntAdora: Profa. Esp. PAtriciA MontEnegro MAtos Albuquerque. FORTALEZA 2019 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação Universidade Federal do Ceará Biblioteca Universitária Gerada automaticamente pelo módulo Catalog, mediante os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a) T266b Teixeira, Johann Freitas. Björk e seu coração partido : uma analise das relações entre figurino e design gráfico a partir do encarte do álbum vulnicura / Johann Freitas Teixeira. – 2019. 60 f. : il. color. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (graduação) – Universidade Federal do Ceará, Instituto de cultura e Arte, Curso de Design de Moda, Fortaleza, 2019. Orientação: Profa. Esp. Patricia Montenegro Matos Albuquerque. 1. Figurino . 2. Design gráfico. 3. Encarte. 4. Björk. I. Título. CDD 391 JOHANN FREITAS TEIXEIRA BJÖRK E SEU CORAÇÃO PARTIDO: UMA ANÁLISE DAS RELAÇÕES ENTRE FIGURINO E DESIGN GRÁFICO A PARTIR DO ENCARTE DO ÁLBUM VULNICURA MonografiA ApresEntAda como conclusão de Curso Em DEsign-Moda do Instituto de Cultura E ArtE – ICA da Universidade FEderal do CeArá – UFC, como requisito parciAl para obtEnção de Título de Bacharel em DEsign-Moda. -

Relatório Final

Relatório de Bolsa de Iniciação Científica Relatório Final Número do Processo: 2018/11470-1 Nome do Projeto: Inovação Audiovisual e a Voz Política em Let England Shake, Biophilia e Lemonade Vigência: 01/10/2018 a 30/09/2019 Período coberto pelo relatório: 10/03/2019 - 30/09/2019 Nome do Beneficiário/Bolsista: Fernando Paes de Oliveira Chaves Guimarães Nome do Responsável/Orientador: Cecília Antakly de Mello Fernando Paes de Oliveira Chaves Guimarães Cecília Antakly de Mello b) Resumo do plano inicial e das etapas já descritas em relatórios anteriores O projeto Inovação audiovisual e a voz política em Let England Shake, Biophilia e Lemonade teve como proposição inicial a investigação de novas formas audiovisuais que, de certo modo, são derivadas dos videoclipes e compõem um amálgama entre música e audiovisual. Em um primeiro momento, foi realizada uma extensa pesquisa sobre a história do videoclipe, suas origens e influências formais. Para essa pesquisa, utilizei uma bibliografia extensa, composta por autores como Arlindo Machado, Ken Dancyger, Kristin Thompson e David Bordwell, Flora Correia e Carol Vernallis. A obra Experiencing Music Video, de Carol Vernallis foi muito importante para o desenvolvimento da pesquisa e o uso da reserva técnica da bolsa para a aquisição dessa obra foi fundamental, uma vez que não a encontrei em bibliotecas públicas. Após o levantamento bibliográfico incial, foi realizada uma pesquisa sobre a biografia das artistas, de modo a possibilitar um melhor entendimento do contexto em que cada uma das obras foi lançada e a trajetória das três artistas até o momento de criação dos álbuns. Em seguida, realizei uma análise meticulosa de Let England Shake e Lemonade. -

Mediated Music Makers. Constructing Author Images in Popular Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 10th of November, 2007 at 10 o’clock. Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. © Laura Ahonen Layout: Tiina Kaarela, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies ISBN 978-952-99945-0-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-4117-4 (PDF) Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. ISSN 0785-2746. Contents Acknowledgements. 9 INTRODUCTION – UNRAVELLING MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP. 11 Background – On authorship in popular music. 13 Underlying themes and leading ideas – The author and the work. 15 Theoretical framework – Constructing the image. 17 Specifying the image types – Presented, mediated, compiled. 18 Research material – Media texts and online sources . 22 Methodology – Social constructions and discursive readings. 24 Context and focus – Defining the object of study. 26 Research questions, aims and execution – On the work at hand. 28 I STARRING THE AUTHOR – IN THE SPOTLIGHT AND UNDERGROUND . 31 1. The author effect – Tracking down the source. .32 The author as the point of origin. 32 Authoring identities and celebrity signs. 33 Tracing back the Romantic impact . 35 Leading the way – The case of Björk . 37 Media texts and present-day myths. .39 Pieces of stardom. .40 Single authors with distinct features . 42 Between nature and technology . 45 The taskmaster and her crew. -

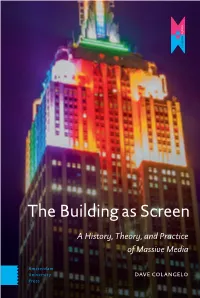

The Building As Screen

media media matters The Building as Screen A History, Theory, and Practice of Massive Media Amsterdam University dave colangelo Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS The Building as Screen FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS MediaMatters is an international book series published by Amsterdam University Press on current debates about media technology and its extended practices (cultural, social, political, spatial, aesthetic, artistic). The series focuses on critical analysis and theory, exploring the entanglements of materiality and performativity in ‘old’ and ‘new’ media and seeks contribu- tions that engage with today’s (digital) media culture. For more information about the series see: www.aup.nl FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS The Building as Screen A History, Theory, and Practice of Massive Media Dave Colangelo Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Cover illustration: The Empire State Building with Philips Color Kinetics System. Photo: Anthony Quintano, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. Layout: Sander Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 949 8 e-isbn 978 90 4854 205 5 doi 10.5117/9789462989498 nur 670 © D. Colangelo / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2020 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

The Subject of Music As Subject of Excess and Emergence: Resonances and Divergences Between Slavoj Žižek and Björk Guðmundsdóttir

ISSN 1751-8229 Volume Eleven, Number Three The Subject of Music as Subject of Excess and Emergence: Resonances and Divergences between Slavoj Žižek and Björk Guðmundsdóttir Jérôme Melançon, University of Regina (Canada) Alexander Carpenter, University of Alberta (Canada) Abstract In answering the question “who is the subject of music,” we argue that it is a subject of excess and emergence, and we rely on the definition and development of these terms by Žižek and Björk. Such a subject is movement and activity; it exceeds the experiences, objects, others and symbolic order that make it who it is; and it emerges through desire and drive, and resonance and animation. We open with a brief discussion of Žižek’s subject of excess, which we then relate to his approach to subjectivity in music. After an analysis of Björk’s music, centered on the piece “Black Lake” and from a perspective informed by Žižek’s account of subjectivity, we shift our attention to Björk’s thoughts on music in order to find elements that allow for the development of a subject of emergence. While the elements of excess and emergence are present in both accounts of the subject, Žižek’s and Björk’s respective focus on one of these concepts allow us to develop a fuller picture of subjectivity, particularly but not exclusively as it is engaged with in musical activities. Key Words: Subjectivity; Creation; Self-Transformation; Resonance; Popular Music; Classical Music; Musical Subjectivization Overture Who is the subject of music? Who is the subject who sings and plays, rather than simply speaking and working—whose speaking is singing and whose work is playing? Such a question is easily answered with reference to the subject of expression, who speaks and sings because it has something to say. -

Documento En

Información Importante La Universidad de La Sabana informa que el(los) autor(es) ha(n) autorizado a usuarios internos y externos de la institución a consultar el contenido de este documento a través del Catálogo en línea de la Biblioteca y el Repositorio Institucional en la página Web de la Biblioteca, así como en las redes de información del país y del exterior con las cuales tenga convenio la Universidad de La Sabana. Se permite la consulta a los usuarios interesados en el contenido de este documento para todos los usos que tengan finalidad académica, nunca para usos comerciales, siempre y cuando mediante la correspondiente cita bibliográfica se le de crédito al documento y a su autor. De conformidad con lo establecido en el artículo 30 de la Ley 23 de 1982 y el artículo 11 de la Decisión Andina 351 de 1993, La Universidad de La Sabana informa que los derechos sobre los documentos son propiedad de los autores y tienen sobre su obra, entre otros, los derechos morales a que hacen referencia los mencionados artículos. BIBLIOTECA OCTAVIO ARIZMENDI POSADA UNIVERSIDAD DE LA SABANA Chía - Cundinamarca E M P T I N E S S María Alejandra Amaya Cáez Angie Katherin Franco Borda Jessica Tatiana Lozano Vargas Angie Daniela Muñoz Soriano Proyecto creativo de carácter audiovisual: Video experimental Sergio Roncallo Dow Doctor en Filosofía Universidad de La Sabana Facultad de Comunicación Comunicación Audiovisual y Multimedios Chía, Cundinamarca. 2016 RESUMEN Emptiness es un video experimental que representa una crítica concreta a la sociedad contemporánea. Esta crítica se expresa a través de la ruptura de la realidad y la fragmentación del ser, haciendo énfasis en los distintos egos que aprisionan al espíritu, la mente, y a la humanidad. -

Universidade Federal Do Ceará Centro De Humanidades Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Estudos Da Tradução

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ CENTRO DE HUMANIDADES PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ESTUDOS DA TRADUÇÃO JEFFERSON CÂNDIDO NUNES A TRANSMUTAÇÃO MONADOLÓGICA DE BJÖRK: TRADUÇÃO INTERSEMIÓTICA DA DOR EM TRÊS DIMENSÕES, A PARTIR DE BLACK LAKE FORTALEZA 2017 JEFFERSON CÂNDIDO NUNES A TRANSMUTAÇÃO MONADOLÓGICA DE BJÖRK: TRADUÇÃO INTERSEMIÓTICA DA DOR EM TRÊS DIMENSÕES, A PARTIR DE BLACK LAKE Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Estudos da Tradução da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Estudos da Tradução. Área de concentração: Processos de Retextualização. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Robert Brose Pires. FORTALEZA 2017 JEFFERSON CÂNDIDO NUNES A TRANSMUTAÇÃO MONADOLÓGICA DE BJÖRK: TRADUÇÃO INTERSEMIÓTICA DA DOR EM TRÊS DIMENSÕES, A PARTIR DE BLACK LAKE Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Estudos da Tradução da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Estudos da Tradução. Área de concentração: Processos de Retextualização. Aprovada em: ___/___/______. BANCA EXAMINADORA ________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Robert Brose Pires (Orientador) Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) _________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Carlos Augusto Viana da Silva Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) _________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Suene Honorato de Jesus Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) À família, aos amigos. AGRADECIMENTOS À minha família, em especial e com amor maior à minha irmã – Fernanda – e à minha mãe – Ana –, que sempre me apoiam e me incentivam a ir cada vez mais longe. Aos parentes que entendem que “família não é sangue; família é sintonia”. Aos bons amigos – principalmente àquele grupo de pessoas com nomes iniciados em “m”. -

2017 Dis Jpmonteiro.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ INSTITUTO DE CULTURA E ARTE PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO JULIO PIO MONTEIRO NOMADISMO SENSÍVEL: ESTÉTICA DO VIDEOCLIPE E TENSIONAMENTOS EM STONEMILKER E BLACK LAKE FORTALEZA 2017 JULIO PIO MONTEIRO NOMADISMO SENSÍVEL: ESTÉTICA DO VIDEOCLIPE E TENSIONAMENTOS EM STONEMILKER E BLACK LAKE Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Comunicação da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de mestre em Comunicação. Área de concentração: Fotografia e Audiovisual. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Osmar Gonçalves dos Reis Filho FORTALEZA 2017 ___________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________ JULIO PIO MONTEIRO NOMADISMO SENSÍVEL: ESTÉTICA DO VIDEOCLIPE E TENSIONAMENTOS EM STONEMILKER E BLACK LAKE Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Comunicação da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de mestre em Comunicação. Área de concentração: Fotografia e Audiovisual. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Osmar Gonçalves dos Reis Filho Aprovada em: ___/___/______. BANCA EXAMINADORA ________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Osmar Gonçalves dos Reis Filho (Orientador) Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) _________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Henrique Codato Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) _________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Thiago Soares Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE) A meus pais, Francisca e Júlio. Ao meu sim-fim de corações, minhas irmãs. Aos meus amigos. A cada adolescente estranho no mundo. AGRADECIMENTOS Obrigado aos meus amigos que estiveram comigo durante esta jornada tão complicada. Obrigado por morarem em mim. Eu não posso numerar todos. Sou bom com afetos, não com palavras. Obrigado aos meus pais. À minha mãe, matriarca forte que soube me dar carinho e força. À meu pai, para que eu nunca esqueça de quem ele é. -

Shellie Trierweiler English 122, Section 007 Miss French February

Shellie Trierweiler English 122, section 007 Miss French February 23, 2011 Evolution of an Artist: Expansion of Me Fearless Expression Her name? Regularly mispronounced. Her music? Impossible to categorize. Her avant- garde visual artistry? Often misunderstood. Her voice? So matchless, many refer to it as being from another world. Björk, a brilliant vocalist from Iceland, has transcended her early origins as an eclectic dance and pop star and evolved into an international superstar who gained critical acclaim as a composer, musician, and songstress entirely untouched by conformity. Björk Gumundsdottir is the full name given to her at birth. Most English-speaking people, including myself, have incorrectly assumed it is pronounced (Bee-york). Björk, herself clears up the common confusion by stating in an NPR interview, “(BE-yerk) I usually say it rhymes with jerk. You know if someone is a real jerk.” Throughout her career, she has delved into an eclectic blend of genres, combining an innovative mix of folk, punk rock, collegiate rock, alternative, electronica, pop, trip-hop, jazz, experimental, and folk, just to name a few. As Björk matures, she expands our perception of what is, and what creates, musical sounds. She combines volcanic beats—yes…literally gathered by engineers from a volcano—with classical orchestral strings, to bring amazing songs to life. Björk was classically trained in piano and voice as a child and recorded her first album when she was 11 years old. It was a compilation of Icelandic folk cover songs that she was not particularly fond of. In the documentary film, Inside Björk, she admits, “I felt funny about Trierweiler 2 having an album out that said Björk on it, but it wasn’t my work. -

Björk and Michel Gondry's Networked Authorship

!"#$%&'()&*+,-./&01()$234&5.671$%.)&896-1$4-+:;& <-.&*94+,&=+).1&'4&'&*1).&1>&?146@A+(.B'6+,&?$',6+,.&'()&6-.&?146@A1/1(+'/&C9D".,6&'4&*+(1$& 896-1$E& & & & & F./+:.&01B.G&!1(+//'& & & & 8&<-.4+4! +(! <-.&*./&H1::.(-.+B&C,-11/&1>&A+(.B'& & & & ?$.4.(6.)&+(&?'$6+'/&F9/>+//B.(6&1>&6-.&I.J9+$.B.(64& >1$&6-.&K.L$..&1>&*'46.$&1>&8$64&MF+/B&C69)+.4N&'6& A1(,1$)+'&O(+P.$4+62& *1(6$.'/Q&R9SD.,Q&A'(')'& & & & & ! & & & & & & & T'(9'$2&UVUW! X&F./+:.&01B.GQ&UVUW& !"#!"$%&'()#&*+$,&-.( ,/0112(13(4567869:(,987;:<& <-+4&+4&61&,.$6+>2&6-'6&6-.&6-.4+4&:$.:'$.)&& !2;& F./+:.&01B.G&!1(+//'& Y(6+6/.);& !"#$%&'()&*+,-./&01()$234&5.671$%.)&896-1$4-+:;& <-.&*94+,&=+).1&'4&'&*1).&1>&?146@A+(.B'6+,&?$',6+,.&'()&6-.&?146@A1/1(+'/& C9D".,6&'4&*+(1$&896-1$E& &&&&&&'()&49DB+66.)&+(&:'$6+'/&>9/>+//B.(6&1>&6-.&$.J9+$.B.(64&>1$&6-.&).L$..&1>& =6<9:5(13('59<(>?;2@(,987;:<A( ,1B:/+.4&7+6-&6-.&$.L9/'6+1(4&1>&6-.&O(+P.$4+62&'()&B..64&6-.&',,.:6.)&46'()'$)4&7+6-&$.4:.,6&61& 1$+L+('/+62&'()&J9'/+62E&& C+L(.)&D2&6-.&>+('/&YZ'B+(+(L&A1BB+66..;& YZ'B+(.$&M[(6.$('/N& "#$%!&'()*+($,-!./0! YZ'B+(.$&MYZ6.$('/N& ")$)#1!0(!234#-!./0! C9:.$P+41$& 234#**#!"#56(-!./0! 8::$1P.)&D2&\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\ "#$%!&'()*+($,!./0-&0$')9'6.&?$1L$'B&K+$.,61$& \\\\\\\\\\\\&UVUW \\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\& K.'(&1>&F',9/62Q&K$E&8((+.&0S$+(& && ( 'B,-$'!-& & !"#$%&'()&*+,-./&01()$234&5.671$%.)&896-1$4-+:;& <-.&*94+,&=+).1&'4&'&*1).&1>&?146@A+(.B'6+,&?$',6+,.&'()&6-.&?146@A1/1(+'/&C9D".,6&'4&*+(1$& 896-1$E& & & F./+:.&01B.G&!1(+//'! & & & <-+4&6-.4+4&6-.1$+G.4&6-.&W]]V4&B94+,&P+).14&D2&[,./'()+,&:.$>1$B.$&!"#$%&'()&F$.(,-&)+@