Indian Folklife Volume 3 Issue 3 Serial No. 1 6 July 2004 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report (PDF)

The First Intensive Researchers Meeting on Communities and the 2003 Convention: “Documentation of Intangible Cultural Heritage as a Tool for Community’s Safeguarding Activities” FINAL REPORT 3–4 MarchIRCI 2012 Tokyo, Japan Organised by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) The First Intensive Researchers Meeting on Communities and the 2003 Convention: “Documentation of Intangible Cultural Heritage as a Tool for Community’s Safeguarding Activities” FINAL REPORT 3–4 March 2012 Tokyo, Japan Organised by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) Published by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) c/o Sakai City Museum, 2 cho Mozusekiun-cho, Sakai-ku, Sakai-city, Osaka 590-0602, Japan [email protected] Editorial Design by Yasuyuki Uzawa Printed by Bigaku-Shuppan, JULY 2012 © International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage In the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), 2012 All photographs on the cover page are part of the Archives and Community Partnership project of the Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology, American Institute of Indan Studies (ARCE). Copyright ARCE. Table of Contents 1. Foreword ...................................................................................................................... 6 2. Proceedings ................................................................................................................. 8 3. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

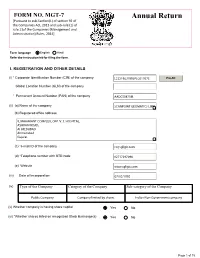

Annual Return

FORM NO. MGT-7 Annual Return [Pursuant to sub-Section(1) of section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and sub-rule (1) of rule 11of the Companies (Management and Administration) Rules, 2014] Form language English Hindi Refer the instruction kit for filing the form. I. REGISTRATION AND OTHER DETAILS (i) * Corporate Identification Number (CIN) of the company Pre-fill Global Location Number (GLN) of the company * Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the company (ii) (a) Name of the company (b) Registered office address (c) *e-mail ID of the company (d) *Telephone number with STD code (e) Website (iii) Date of Incorporation (iv) Type of the Company Category of the Company Sub-category of the Company (v) Whether company is having share capital Yes No (vi) *Whether shares listed on recognized Stock Exchange(s) Yes No Page 1 of 15 (a) Details of stock exchanges where shares are listed S. No. Stock Exchange Name Code 1 (b) CIN of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Pre-fill Name of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Registered office address of the Registrar and Transfer Agents (vii) *Financial year From date 01/04/2020 (DD/MM/YYYY) To date 31/03/2021 (DD/MM/YYYY) (viii) *Whether Annual general meeting (AGM) held Yes No (a) If yes, date of AGM (b) Due date of AGM (c) Whether any extension for AGM granted Yes No II. PRINCIPAL BUSINESS ACTIVITIES OF THE COMPANY *Number of business activities 1 S.No Main Description of Main Activity group Business Description of Business Activity % of turnover Activity Activity of the group code Code company J J8 III. -

BYJU's IAS Monthly Magazine Answer

UPSC Monthly Magazine Answer Key – October 2020 Q1. Which of the following could be the reason/s for Current Account Deficit? 1. Overvalued exchange rate 2. Increase in exports 3. Long periods of consumer-led economic growth 4. High inflation Choose the correct option: a. 1, 3 and 4 only b. 2, 3 and 4 only c. 2 only d. 1 and 4 only Answer: a Explanation: The current account deficit is a measurement of a country’s trade where the value of the goods and services it imports exceeds the value of its exports. If the currency is overvalued, imports will be cheaper, and therefore there will be a higher quantity of imports resulting in a Current Account Deficit. One of the reasons for the Current Account Surplus is an increase in exports. A period of consumer-led economic growth will cause deterioration in the current account. Higher consumer spending will lead to higher spending on imports. The recession of 2009 also led to a temporary improvement in the deficit as consumers cut back on spending. If a country’s inflation rises faster than its main competitors then it will make the exports less competitive and imports more competitive for that country. This will lead to deterioration in the current account. Q2. Consider the following statements with respect to the Environment Pollution Control Authority (EPCA): 1. EPCA is a Supreme Court-mandated body tasked with taking various measures to tackle air pollution in all the metropolitan cities across India. 2. System of Air Quality and Weather Forecasting and Research (SAFAR) is a national initiative introduced by EPCA. -

3Rd All India Media Educators' Conference-2018 on Power of Media and Technology: Shaping the Future

CONFERENCE REPORT 3RD ALL INDIA MEDIA EDUCATORS' CONFERENCE-2018 ON POWER OF MEDIA AND TECHNOLOGY: SHAPING THE FUTURE July 6 - 8, 2018 Geeta Girdhar Sabhagaar Pearl Academy of Fashion Designing & Media Jaipur Jointly Organised By: Centre for Mass Communication, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Department of Communication & Journalism, Gauhati University, Guwahati Lok Samvad Sansthan, Jaipur Submitted By: Kalyan Singh Kothari Secretary Lok Samvad Sansthan BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT During the last 70 years since Independence, the position of media has taken a radical shift in India. The ingrained transformation of the Indian society during its journey in the last seven decades, especially in the post-globalization period, has left a noteworthy impact on media. The evolution has also placed challenges before the Indian media scenario. The character of these challenges has kept on changing with the emergence of new social, cultural and political context and has assumed a new perspective following the advent of information technology, Internet and social media, visible in the multiplicity of platforms. The Indian media had a sound role in the struggle for Independence. But it faces a challenge in the present scenario to maintain its high standards commensurate with its glorious past. Subsequently, the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has been entering into all forms of media. Though the entertainment media industry has been the prime area of FDI, the other genres like print, electronic even radio industries are now becoming lucrative targets of FDI. Though a focus is laid on the expansion of facilities or creation of new geographic market to speak high about FDI in media sector, experience and apprehensions point to several negative aspects. -

Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016

All Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016 Yea Sub Artist Name Field Category r Category Prabhakar Karekar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Padma Talwalkar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Koushik Aithal - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Yuva Puraskar 6 Yashasvi 201 Sirpotkar - Yuva Music Hindustani Vocal 6 Puraskar Arvind Mulgaonkar - 201 Music Hindustani Tabla Akademi 6 Awardee Yashwant 201 Vaishnav - Yuva Music Hindustani Tabla 6 Puraskar Arvind Parikh - 201 Music Hindustani Sitar Akademi Fellow 6 Abir hussain - 201 Music Hindustani Sarod Yuva Puraskar 6 Kala Ramnath - 201 Akademi Music Hindustani Violin 6 Awardee R. Vedavalli - 201 Music Carnatic Vocal Akademi Fellow 6 K. Omanakutty - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Neela Ramgopal - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Srikrishna Mohan & Ram Mohan 201 (Joint Award) Music Carnatic Vocal 6 (Trichur Brothers) - Yuva Puraskar Ashwin Anand - 201 Music Carnatic Veena Yuva Puraskar 6 Mysore M Manjunath - 201 Music Carnatic Violin Akademi 6 Awardee J. Vaidyanathan - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee Sai Giridhar - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee B Shree Sundar 201 Kumar - Yuva Music Carnatic Kanjeera 6 Puraskar Ningthoujam Nata Shyamchand 201 Other Major Music Sankirtana Singh - Akademi 6 Traditions of Music of Manipur Awardee Ahmed Hussain & Mohd. Hussain (Joint Award) 201 Other Major Sugam (Hussain Music 6 Traditions of Music Sangeet Brothers) - Akademi Awardee Ratnamala Prakash - 201 Other Major Sugam Music Akademi -

Debit Cards - Bookmyshow Voucher Winners

Cards Engagement Promo - Debit Cards - BookMyShow Voucher Winners S No. Masked Card Nos. Winners' List 1 4143********5150 ARVIND V 2 4181********3074 USHA DEEPAK KADAM, DEEPAK KADAM 3 4143********7658 SANDEEP H CHAWDA 4 4689********0641 ASHIN 5 4143********1326 ROHAN ANIL KULKARNI 6 4572********5325 GARIMA SHARMA 7 5166********1876 PRASHANT HARALE 8 5166********0912 SURYANARAYANA RAJU VATSAVAYI 9 4018********2503 K V AISHWARAYA ALICE 10 4018********1606 LEELA BISHT 11 4799********1776 ABHAY HARI SARODE 12 5594********1936 ROHIT RAJARAM MALI 13 4017********0189 KOKILA BALASUBRAMANI 14 4143********5786 PIYUSH KUMAR 15 4799********0661 ACHAL SHRIVASTAVA 16 5166********0798 RAHUL JIJ 17 4143********0603 PAVITHRA S 18 4018********5154 KARTIK MALVIYA 19 4018********8314 SHINU BABU 20 4018********1399 KALLA SAI VENKATA HAINDHAVI 21 4018********4505 NITISH ANAND 22 5594********1417 RAJESH BORUSU 23 5166********2877 ANANDHA PRABU A M 24 4722********2954 HITESH CHOPRA 25 4143********4318 YESHA KAMLESHKUMAR PARIKH 26 4722********6374 SWARNALI NANDY 27 4018********6997 NIKHIL JAYANTILAL RATHOD 28 4143********0203 RAKESH VETAGIRE 29 4799********0646 SWAMINATHAN GANESHRAJA 30 4722********4071 ADHISHTHATRI AMUL MOREKAR 31 4722********3376 SAUMYA RAIZADA 32 5166********7267 HEINZE CLETUS 33 4017********0455 MARGANA HARIKA 34 4722********6181 AKSHAY BHUTDA 35 4018********6601 ADITENDRA SINGH 36 4143********7923 ROBY TOM/VIMALA ROBY JOSEPH 37 4693********9417 HIREN KAMAL BHATIA (JT) 38 4799********1893 LAXMISHA CHANDRASHEKAR 39 4017********6858 NILESH -

Festival of Letters 2014

DELHI Festival of Letters 2014 Conglemeration of Writers Festival of Letters 2014 (Sahityotsav) was organised in Delhi on a grand scale from 10-15 March 2014 at a few venues, Meghadoot Theatre Complex, Kamani Auditorium and Rabindra Bhawan lawns and Sahitya Akademi auditorium. It is the only inclusive literary festival in the country that truly represents 24 Indian languages and literature in India. Festival of Letters 2014 sought to reach out to the writers of all age groups across the country. Noteworthy feature of this year was a massive ‘Akademi Exhibition’ with rare collage of photographs and texts depicting the journey of the Akademi in the last 60 years. Felicitation of Sahitya Akademi Fellows was held as a part of the celebration of the jubilee year. The events of the festival included Sahitya Akademi Award Presentation Ceremony, Writers’ Meet, Samvatsar and Foundation Day Lectures, Face to Face programmmes, Live Performances of Artists (Loka: The Many Voices), Purvottari: Northern and North-Eastern Writers’ Meet, Felicitation of Akademi Fellows, Young Poets’ Meet, Bal Sahiti: Spin-A-Tale and a National Seminar on ‘Literary Criticism Today: Text, Trends and Issues’. n exhibition depicting the epochs Adown its journey of 60 years of its establishment organised at Rabindra Bhawan lawns, New Delhi was inaugurated on 10 March 2014. Nabneeta Debsen, a leading Bengali writer inaugurated the exhibition in the presence of Akademi President Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari, veteran Hindi poet, its Vice-President Chandrasekhar Kambar, veteran Kannada writer, the members of the Akademi General Council, the media persons and the writers and readers from Indian literary feternity. -

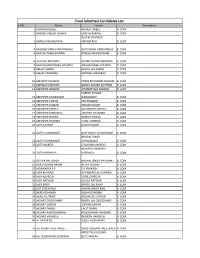

Final Admitted Candidates List S.NO

Final Admitted Candidates List S.NO. Name Fname Description 1 AAKARSH BABEL BHARAT BABEL B. COM 2 AAKASH UMESH ASAWA UMESH ASAWA B. COM ASEEM SHANKER 3 AARUSH SRIVASTAVA SRIVASTAVA B. COM 4 AASHISH SINGH YADUVANSHI DILIP SINGH YADUVANSHI B. COM 5 AAYUSH MAHESHWARI DINESH MAHESHWARI B. COM 6 AAYUSHI MENARIA HUKMI CHAND MENARIA B. COM 7 AAYUSHMAN SINGH SOLANKI JEEVAN SINGH SOLANKI B. COM 8 ABHAY KABRA BHERU LAL KABRA B. COM 9 ABHAY LAKSHKAR MUKESH LAKSHKAR B. COM 10 ABHIJEET PALIWAL PRADEEP KUMAR PALIWAL B. COM 11 ABHINAV KOTHARI ABHAY KUMAR KOTHARI B. COM 12 ABHISHEK ANJANA GHANSHYAM ANJANA B. COM SURESH KUMAR 13 ABHISHEK GANGAWAT GANGAWAT B. COM 14 ABHISHEK KHATIK OM PRAKASH B. COM 15 ABHISHEK KUMAR ARJUN KUMAR B. COM 16 ABHISHEK MEHTA MAHENDRA MEHTA B. COM 17 ABHISHEK MENARIYA JAGDISH CHANDRA B. COM 18 ABHISHEK NAGDA DINESH NAGDA B. COM 19 ABHISHEK SHARMA SUNIL SHARMA B. COM 20 ACHLA SINGH RAJESH SINGH B. COM 21 ADITI CHUNDAWAT AJAY SINGH CHUNDAWAT B. COM BHOPAL SINGH 22 ADITI CHUNDAWAT CHUNDAWAT B. COM 23 ADITI MAROO GYAN MAL MAROO B. COM MAHESH CHANDRA 24 ADITI NARANIYA NARANIYA B. COM 25 ADITYA PAL SINGH BHUPAL SINGH PATRABAT B. COM 26 AIJAZ HUSAIN HAKIM ALTAF HUSAIN B. COM 27 AISHWARYA E P E P PRAKASH B. COM 28 AJAY KHARADI BHANWAR LAL KHARADI B. COM 29 AJAY KUKREJA SUNIL KUKREJA B. COM 30 AJAY PATIDAR DHULJI PATIDAR B. COM 31 AJAY SALVI BHERU LAL SALVI B. COM 32 AJIT SINGH RAO NAHAR SINGH RAO B. COM 33 AKASH DAHIMA KISHAN DAHIMA B. -

Outgoing Cultural Delegations April, 2010 – March, 2011

Annexure 2 OUTGOING CULTURAL DELEGATIONS APRIL, 2010 – MARCH, 2011 COUNTRIES NAME OF THE GROUP S.NO. VISITED DATE PURPOSE OF VISIT REMARKS 1. Reunion 10-member Manipuri Dance group “Meitei 4 – 19 April, 2010 To participate in the Tamil New Year Island Traditional Dance” led by Ms. Indira Devi, Celebrations in Reunion Island Manipur 2. USA Prof. T.R.Subramanyam and Dr. Radha 14 April – 29 June, To give cultural performances to coincide Venkatachalam (Carnatic Vocal), Tamilnadu 2010 with the G.N. Balasubramaniam (GNB) Two travel grants Global Centenary Celebrations 3. Singapore 10-member Punjabi Theatre group of 22 – 24 April, 2010 To participate in the Baisakhi Mela “Amritsar Natak Kala Kendra led by Ms. Areet Kaur, Punjab 4. Malaysia 14-member Bhangra and Giddha group 22 – 26 April, 2010 To perform at the Baisakhi Celebrations “Jugni Cultural and Youth” led by Shri Davinder Singh, Punjab 5. Cambodia 6-member Manipuri Dance group led by Ms. 24 April – 1 May, To give cultural performances on the Rina Devi, Manipur 2010 occasion of “Trail of Civilization” in Siem Riep, Cambodia 6. Zimbabwe 12-member Gujarati Folk Dance group 25 April – 9 May, To participate in the Harare International South Africa “Yuvak Mandal Gadhavi” led by Shri Bhoye 2010 Festival of Arts (HIFA) in Zimbabwe and to Shivaji Kaprubhai, Gujarat give cultural performances in South Africa 7. Germany 14 travel grants to Children group from 1 - 10 May, 2010 To participate in the Children Choir Festival Bangalore Music School, Karnataka Fourteen travel grants 8. Singapore 4-member Rabindra Sangeet group led by 10 – 15 May, 2010 To give cultural performances during a Malaysia Shri Prabuddha Raha, West Bengal Conference “An Age in Motion : The Asian Voyage of Rabindranatha Tagore” 9. -

Some Facts About Rajasthan 2020 Pdf

Some facts about rajasthan 2020 pdf Continue State in Northern India This article is about the Indian state. In the area of the ancient city of Samarkand you can see Registan. For the desert in Afghanistan, see Rigestan. The state in IndiaRajasthanState from above, from left to right: Tar Desert, Gateshwar Mahadeva Temple in Chittorgarha, Jantar Mantar, Jodhpur Blue City, Mount Abu, Amer Fort Seal of Rajasthan in IndiaCoordinates (Jaipur): 26'36'N 73'48'E / 26.6'N 73.8'E / 26.6; 73.8Coordinates: 26'36'N 73'48'E / 26.6'N 73.8'E / 26.6; 73.8Country IndiaEstablished30 March 1949CapitalJaipurLargest cityJaipurDistricts List AjmerAlwarBanswaraBaranBarmerBharatpurBhilwaraBikanerBundiChittorgarhChuruDausaDholpurDungarpurHanumangarhJaipurJaisalmerJalorJhalawarJhunjhunuJodhpurKarauliKotaNagaurPaliPratapgarhRajsamandSawai MadhopurSikarSirohiSri GanganagarTonkUdaipur Government • BodyGovernment of Rajasthan • GovernorKalraj Mishra[1] • Chief MinisterAshok Gehlot (INC) • LegislatureUnicameral (200 seats) • Parliamentary constituencyRajya Sabha (10 seats)Lok Sabha (25 seats) • High CourtRajasthan High CourtArea • Total342,239 km2 (132,139 sq mi)Area rank1stPopulation (2011)[2] • Total68,548,437 • Rank7th • Density200/km2 (520/sq mi)Demonym(s)RajasthaniGSDP (2019–20)[3] • Total₹10.20 lakh crore (US$140 billion) • Per capita₹118,159 (US$1,700)Languages[4] • OfficialHindi • Additional officialEnglish • RegionalRajasthaniTime zoneUTC+05:30 (IST)ISO 3166 codeIN-RJVehicle registrationRJ-HDI (2018) 0.629[5]medium · 29thLiteracy (2011)66.1% Sex ratio (2011)928 ♀/1000 ♂'6'websiteRajasthan.gov.inSymbols Rajast The EmblemEmblem of Rajasthan Dance GhoomarMammal Camel and ChinkaraBird GodawanFlower RohidaTree KhejriGame Basketball Rajasthan (/ˈrɑːdʒəstæn/Hindu pronunciation: raːdʒəsˈthaːn (listen); literally, Land of Kings is a state in northern India. The state covers an area of 342,239 square kilometers (132,139 square miles), or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographic area. -

Los Angeles a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomu

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles FIND THE TRUE COUNTRY: DEVOTIONAL MUSIC AND THE SELF IN INDIA’S NATIONAL CULTURE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by VIVEK VIRANI 2016 © Copyright by Vivek Virani 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Find the True Country: Devotional Music and the Self in India’s National Culture by Vivek Virani Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Daniel M. Neuman, Chair For centuries, the songs of devotional poet-saints have been an integral part of Indian religious life. Countless regional traditions of bhajans (devotional songs) have been able to maintain their existence by adapting to serve the contemporary social needs of their participants. This dissertation draws on fieldwork conducted over 2014-2015 with contemporary bhajan performers from many different genres and styles throughout India. It highlights a specific tradition in the Central Indian region of Malwa based on poetry by Kabir and other Sants (anti- establishment poet-saints) performed by lower-caste singers. This tradition was largely unheard- of half a century ago, but is now a major part of Malwa’s cultural life that has facilitated the creation of lower-caste spiritual networks and created a space for those networks to engage in discourse about social issues. Malwa’s bhajan singers have also become part of India’s popular ii religious and musical life as certain performers have attained celebrity status and been recognized at the national level as living bearers of the Sant tradition. This dissertation follows performers and songs from Malwa into new contexts and explores the processes by which performers and audiences in diverse styles and contexts use Sant bhajans to construct understandings of the self.