Daughters-Of-Messene.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

04-14-2016.Pdf

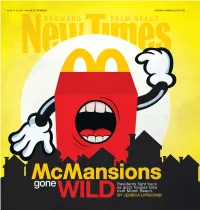

APRIL 14-20, 2016 I VOLUME 19 I NUMBER 25 BROWARDPALMBEACH.COM I FREE NBROWARD PALM BEACH ® BROWARDPALMBEACH.COM ▼ Contents 2450 HOLLYWOOD BLVD., STE. 301A HOLLYWOOD, FL 33020 [email protected] 954-342-7700 VOL. 19 | NO. 25 | APRIL 14-20, 2016 DJ! EDITORIAL ERCULES P32 EDITOR Chuck Strouse WIN A H MANAGING EDITOR Deirdra Funcheon EDITORIAL OPERATIONS MANAGER Keith Hollar browardpalmbeach.com ASSOCIATE WEB EDITOR Jose D. Duran browardpalmbeach.com STAFF WRITERS Laine Doss, Jess Swanson UNFEST 2016! FELLOW Jerry Iannelli TS TO S MUSIC EDITOR Falyn Freyman ARTS & CULTURE/FOOD EDITOR Rebecca McBane WIN A PAIR OF TICKE CLUBS EDITOR Melissa Guzman PROOFREADER Mary Louise English IDOR FROM CONTRIBUTORS Emily Bloch, Nicole Danna, Michelle DeCarion, Doug Fairall, TABLE HUM Abel Folgar, Cristina Jerome, Natalya Jones, Jonathan Kendall, WIN A POR CIGAR BAR! Angel Melendez, Dave Minsky, Andrea Richard, Jesse Richman, WNTOWN David Rolland, Gillian Speiser, Terra Sullivan, John Thomason, DO Sara Ventiera, David Von Bader, Lee Zimmerman | CONTENTS | | CONTENTS TS ART TO THE SHAKY BEA ART DIRECTOR Miche Ratto TS TA! ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR Kristin Bjornsen WIN A PAIR OF TICKETIVAL INAT LAN MUSIC FES PRODUCTION PRODUCTION MANAGER Mike Lugo PRODUCTION ASSISTANT MANAGER Jorge Sesin ADVERTISING ART DIRECTOR Andrea Cruz EWS | PULP EWS Photo by Karli Evans Karli by Photo N ADVERTISING ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Alexis Guillen ONLINE SUPPORT MANAGER Ryan Garcia Y | MARKETING DIRECTOR Jennifer G. Nealon Featured Stories ▼ DA EVENT DIRECTOR CarlaChristina Thompson MARKETING COORDINATOR Kristin Ramos SENIOR ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Sarah Abrahams, Peter Heumann, Kristi Kinard-Dunstan, Andrea Stern McMansions ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Gone Wild taPaige Bresky, Melanie Cruz, Alyson Puccetti Giant homes are taking over CLASSIFIED GE | NIGHT+ ke Miami Beach – and some SENIOR ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES A T Patrick Butters, Ladyane Lopez,s Joel Valez-Stokes residents are fighting back. -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here.. -

Stan Magazynu Caĺ†Oĺıäƒ Lp Cd Sacd Akcesoria.Xls

CENA WYKONAWCA/TYTUŁ BRUTTO NOŚNIK DOSTAWCA ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST 159,99 SACD BERTUS ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST (NUMBERED 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - BROTHERS AND SISTERS (NUMBE 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - EAT A PEACH (NUMBERED LIMIT 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - IDLEWILD SOUTH (GOLD CD) 129,99 CD GOLD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ASIA - ASIA 179,99 SACD BERTUS BAND - STAGE FRIGHT (HYBRID SACD) 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - MUSIC FROM BIG PINK (NUMBERED LIMITED 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - THE LAST WALTZ (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITI 179,99 2 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BASIE, COUNT - LIVE AT THE SANDS: BEFORE FRANK (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BIBB, ERIC - BLUES, BALLADS & WORK SONGS 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - JUST LIKE LOVE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - RAINBOW PEOPLE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - GOOD STUFF 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - SPIRIT & THE BLUES 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BLIND FAITH - BLIND FAITH 159,99 SACD BERTUS BOTTLENECK, JOHN - ALL AROUND MAN 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 CAMEL - RAIN DANCES 139,99 SHMCD BERTUS CAMEL - SNOW GOOSE 99,99 SHMCD BERTUS CARAVAN - IN THE LAND OF GREY AND PINK 159,99 SACD BERTUS CARS - HEARTBEAT CITY (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITION HY 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS AFTER HOURS (NUMBERED LI 99,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS OF RAY CHARLES (NUMBERED 129,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY -

Nr Kat EAN Code Artist Title Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data Premiery Repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl

nr kat EAN code artist title nośnik liczba nośników data premiery repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 19075816432 190758164328 '77 Bright Gloom CD Longplay 1 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 9985848 5051099858480 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us CD Longplay 1 2015-10-30 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 88697636262 886976362621 *NSYNC The Collection CD Longplay 1 2010-02-01 POP 88875025882 888750258823 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC CD Longplay 2 2014-11-11 POP 19075906532 190759065327 00 Fleming, John & Aly & Fila Future Sound of Egypt 550 CD Longplay 2 2018-11-09 DISCO/DANCE 88875143462 888751434622 12 Cellisten der Berliner Philharmoniker, Die Hora Cero CD Longplay 1 2016-06-10 CLASSICAL 88697919802 886979198029 2CELLOS 2CELLOS CD Longplay 1 2011-07-04 CLASSICAL 88843087812 888430878129 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 1 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88875052342 888750523426 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 2 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88725409442 887254094425 2CELLOS In2ition CD Longplay 1 2013-01-08 CLASSICAL 19075869722 190758697222 2CELLOS Let There Be Cello CD Longplay 1 2018-10-19 CLASSICAL 88883745419 888837454193 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD Video Longplay 1 2013-11-05 CLASSICAL 88985349122 889853491223 2CELLOS Score CD Longplay 1 2017-03-17 CLASSICAL 88985461102 889854611026 2CELLOS Score (Deluxe Edition) CD Longplay 2 2017-08-25 CLASSICAL 19075818232 190758182322 4 Times Baroque Caught in Italian Virtuosity CD Longplay 1 2018-03-09 CLASSICAL 88985330932 889853309320 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones -

Pos. Canzoni/Songs Hackett Voti Pos. Canzoni/Songs Hackett Voti Pos

Tab. 3/e: Classifica canzoni Steve Hackett - Ranking Steve Hackett songs Pos. Canzoni/Songs Hackett Voti Pos. Canzoni/Songs Hackett Voti Pos. Canzoni/Songs Hackett Voti Pos. Canzoni/Songs Hackett Voti 1 Spectral mornings 83 20 Deja vu 4 22 Overnight sleeper 2 23 The dealer 1 2 Ace of wands 59 Bay of kings 4 Calmaria 2 Black light 1 3 Everyday 57 The show 4 When the heart rules the mind2 What's my name 1 4 Shadow of hierophant 55 Cell 151 4 Circus of becoming 2 Loving sea 1 5 The steppes 34 Twice around the sun 4 23 St. Elmo's fire 1 Corycian fire 1 6 Star of sirius 30 21 Set your compass 3 The devil is a englishman 1 Strutton ground 1 Please don't touch 30 To a close 3 Can't let go 1 Lost time in Cordoba 1 7 Narnia 29 Concert for Munich 3 Momentum 1 The wheel's turning 1 8 Serpentine song 25 Valley of the kings 3 Out of the body 1 A doll that's made in Japan 1 9 Sierra Quemeda 23 A cradle of swan 3 Funny feeling 1 Tristesse 1 10 Hoping love will last 20 Love song to a Vampyre 3 Leaving 1 Sentimental institution 1 11 Hands of the priestess 17 Darktown 3 Slogans 1 In the heart of the city 1 Camino royale 17 The toast 3 After the ordeal 1 Your own special way 1 12 Hammer in the sand 16 Mechanical Bride 3 Pierrot 1 Jacuzzi 16 Time to get out 3 She moves in memories 1 Icarus ascending 16 How can I 3 The summer backwards 1 13 Clocks 13 Hope I don't wake 3 Starlight 1 14 Kim 11 Days of long ago 3 Second chance 1 The air conditioned nightmare 11 22 Time lapse at Milton Keynes 2 Duel 1 15 Fire on the moon 9 Tigermoth 2 The golden age of steam -

REGLEMENT Jeu « Sony Days 2018 »

REGLEMENT Jeu « Sony Days 2018 » Article 1. - Sociétés Organisatrices Sony Interactive Entertainment ® France SAS, au capital de 40 000 €, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre sous le N° 399 930 593, située 92 avenue de Wagram, 75017 Paris ; Sony Mobile Communications, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre sous le n°439 961 905, située 49-51 quai de Dion Bouton 92800 Puteaux ; Sony Pictures Home Entertainment France SNC, au capital de 107 500 €, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre en date du 02/03/1987 sous le N° 324 834 266, située 25 quai Gallieni, 92150 Suresnes ; Sony Music Entertainment, France, SAS au capital de 2.524.720 €, enregistrée au RCS de Paris sous le n°542 055 603, située 52/54, rue de Châteaudun, 75009 Paris ; SONY France , succursale de Sony Europe Limited, 49-51 quai de Dion Bouton 92800 Puteaux , RCS Nanterre 390 711 323 (ci-après les « Sociétés Organisatrices ») ; organise un jeu avec obligation d’achat uniquement dans les magasins Fnac et Darty ainsi que sur le sites www.fnac.com et www.darty.com (ci-après le « Jeu ») par le biais d’instants gagnants ouverts du 02/04/2018 10h au 15/04/2018 23h59 inclus ouvert aux personnes physiques majeures (sous réserve des dispositions indiquées à l’article 2) résidant en France Métropolitaine (Corse et DROM-COM exclus). Article 2. - Participation Ce jeu est ouvert à toute personne physique majeure, résidant en France métropolitaine (Corse et DROM-COM exclus), à l'exception des mineurs, du personnel de la société organisatrice et des membres des sociétés partenaires de l'opération ainsi que de leur famille en ligne directe. -

Steve Hackett – the Total Experience Live in Liverpool

Steve Hackett – The Total Experience Live In Liverpool (72:34 + 79:32, CD, DVD, InsideOut Music / Sony Music, 2016) Erste unbedachte Reaktion: Schon wieder ein Livealbum von Steve Hackett, ist das wirklich nötig? Doch bereits beim ersten Hördurchgang wird klar: Dieses Album ergibt Sinn, auch wenn in den letzten Jahren bereits „Genesis Revisited: Live at the Royal Albert Hall“ (2014), „Genesis Revisited: Live At Hammersmith“ (2013) und „Live Rails“ (2011) erschienen sind. Sinn deshalb, da man auf „The Total Experience“ wieder mal ein etwas anderes Programm aus der umfangreichen Historie des englischen Gitarristen geboten bekommt. Da wären zum einen diverse Ausschnitte aus seinem letzten, sehr guten Studioalbum „Wolflight“. Dazu gesellen sich diverse Klassiker des Soloschaffens von Hackett, die sich im ersten Teil des Konzertes auf seine Frühwerke „Voyage of The Acolyte“ (1975), „Please Don’t Touch“ (1978) und „Spectral Mornings“ (1979) konzentrieren. Zum anderen bekommt man im zweiten Teil des Konzertes einmal mehr die totale Genesis- Dröhnung verpasst, wobei auch hier auf zum Teil selten gespieltes Material wie ‚Get ‚em Out By Friday‘, ‚After The Ordeal‘ und ‚The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway‘ zurückgegriffen wird, man aber auch immer gerne gehörte Klassiker wie ‚TheMusical Box‘, ‚Firth Of Fifth‘ und das bei den vorherigen Tourneen ausgesparte ‚The Cinema Show‘ zu hören bekommt. Zum Schutz Ihrer persönlichen Daten ist die Verbindung zu YouTube blockiert worden. Klicken Sie auf Video laden, um die Blockierung zu YouTube aufzuheben. Durch das Laden des Videos akzeptieren Sie die Datenschutzbestimmungen von YouTube. Mehr Informationen zum Datenschutz von YouTube finden Sie hier Google – Datenschutzerklärung & Nutzungsbedingungen. YouTube Videos zukünftig nicht mehr blockieren. -

Quadraphonicquad Multichannel Engineers of All Surround Releases

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of all surround releases JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Type Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow MCH Dishwalla Services, State MCH Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Quad Abramson, Mark 1973 Judy Collins Colors of the Day - The Best Of CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD MCH Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD The Outrageous Dr. Stolen Goods: Gems Lifted from P: Alan Blaikley, Ken Quad Adelman, Jack 1972 Teleny's Incredible CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD the Masters Howard Plugged-In Orchestra MCH Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V MCH Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD QSS: Ron & Howard Quad Albert, Ron & Howard 1975 -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Steve Hackett - Genesis Revisited

STEVE HACKETT - GENESIS REVISITED Legendary Genesis guitarist’s first ever Australian tour. Steve Hackett, as the powerhouse guitarist for inarguably one of the most important progressive rock bands ever, has been a guiding influence for musicians and guitarists for over 40 years. Genesis, only ever made it to Australia once, in 1986 – years after Steve and singer Peter Gabriel left the band, so Steve is making it up to fans by bringing some Genesis magic to our shores. Genesis classics “Dance On A Volcano” and “Eleventh Earl Of Mar” have never been performed here, and Steve’s incendiary guitar work on a magnum opus such as “Dancing With The Moonlit Knight” will have jaws dropping. In this special Australian only show, Steve will also perform a couple of songs from his critically acclaimed new album, The Night Siren, before whetting the appetite for a grand finale that will leave fans ecstatic. “I'm thrilled to bring my Genesis Revisited tour to Australia. I'll be playing there for the first time and I'm hugely looking forward to it! It'll be great to meet fans and friends, and I know it's an incredibly beautiful country. I'm bringing a special set, including big favourites like ‘Supper's Ready’, ‘The Musical Box’ and ‘Firth of Fifth’ amongst many other stellar Genesis numbers and some solo. I can't wait!” Steve Hackett Steve is renowned for his dazzling guitar playing but his world class band is equal to the task, presenting extraordinarily proficient performances, sensitive to the original recordings yet adding very clear nuances and personality to the music. -

Katalog Sony Music 16.04.2020.Xlsx

nr kat EAN code artist title nośnik liczba nośników data premiery repertoire 19075816432190758164328'77 Bright Gloom CD Longplay 1 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 19075816441190758164410'77 Bright Gloom Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 88697636262886976362621*NSYNC The Collection CD Longplay 1 2010-02-01 POP 88875025882888750258823*NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC CD Longplay 2 2014-11-11 POP 1907590653219075906532700 Fleming, John & Aly & Fila Future Sound of Egypt 550 CD Longplay 2 2018-11-09 DISCO/DANCE 8887514346288875143462212 Cellisten der Berliner Philharmoniker, Die Hora Cero CD Longplay 1 2016-06-10 CLASSICAL 1907592212219075922122821 Savage i am > i was CD Longplay 1 2019-01-11 RAP/HIPHOP 1907592212119075922121121 Savage i am > i was Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2019-03-01 RAP/HIPHOP 886979198028869791980292CELLOS 2CELLOS CD Longplay 1 2011-07-04 CLASSICAL 888430878128884308781292CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 1 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 888750523428887505234262CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 2 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 887254094428872540944252CELLOS In2ition CD Longplay 1 2013-01-08 CLASSICAL 190758697221907586972222CELLOS Let There Be Cello CD Longplay 1 2018-10-19 CLASSICAL 888837454198888374541932CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD Video Longplay 1 2013-11-05 CLASSICAL 889853491228898534912232CELLOS Score CD Longplay 1 2017-03-17 CLASSICAL 889854611028898546110262CELLOS Score (Deluxe Edition) CD Longplay 2 2017-08-25 CLASSICAL 190759538011907595380123TEETH METAWAR Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2019-07-05 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 190759537921907595379233TEETH