Allegory and Setting in HG Wells' the Island of Dr. Moreau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

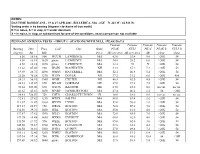

Daytime Bandscans

NOTES: DAYTIME BANDSCANS - 19 & 27 APR 2001 -BILLERICA, MA - (GC= 71.221 W / 42.533 N) Sorting order is by bearing (degrees clockwise of true north) N = in noise, S = in slop, U = under dominant X = in noise, in slop, or subdominant for one of the conditions, exact comparison not available PENNANT ANTENNA TESTS - GROUP 1 - STATIONS WITH NULL / PEAK DATA Pennant Pennant Pennant Pennant Pennant Bearing Dist. Freq. Call City State/ PEAK NULL PK-N PEAK R NULL R degrees km kHz Prov. dB over zero dB over zero dB ohms ohms 8.56 16.18 800 WCCM LAWRENCE MA 63.0 53.4 9.6 >20K 54 8.56 16.18 1620 pirate LAWRENCE MA 34.8 28.2 6.6 >20K 54 8.56 16.18 1670 pirate LAWRENCE MA 22.8 N X >20K 54 14.62 87.04 930 WGIN ROCHESTER NH 44.4 37.2 7.2 >20K 54 19.89 28.72 1490 WHAV HAVERHILL MA 52.2 46.8 5.4 >20K 54 22.20 78.58 1270 WTSN DOVER NH 37.2 31.2 6.0 >20K 486 24.21 56.10 1540 WGIP EXETER NH 46.8 42.0 4.8 >20K 54 24.81 139.07 870 WLAM GORHAM ME 27.0 19.2 7.8 >20K 54 36.61 322.00 620 WZON BANGOR ME 24.0 24.0 0.0 no var. no var. 41.83 43.83 1450 WNBP NEWBURYPORT MA 47.4 46.2 1.2 54 >20K 54.81 758.59 720 CHTN CHARLOTTETOWN PI 18.0 18.0 0.0 no var. -

Return Of,Organization Exempt from Income

Form 990 Return of,Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung 2001 benefit trust or private foundation) Oepartment al the Treasury Open to Public Internal Revenue Semce The organization may have py of this return to sahsty, state reporting requirements A For the 2001 calendar OR tax year beginning JULY 1 2001 , and ending JUNE B Check d applicable C Name of organization D Employer identification number Please Address change use IRS 13-3002025 label or P mail is 0elrvereE address) Name change poor or Number and street (or O box if not to street I RooMsuite E Telephone number type Initial return Sea (212) 529-5300 Specific Final return or town State ZIP r q F Insuue City or country Accounting method Cash Accrual tons D I Amended return ANEW YORK NY E) Other (specify) F-JApplicaiion pending Section 501(c)(3) organizations and4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable 1 and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations trusts must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990-Q) H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? 1:1 Yes ~ No H(b) If -Yes ." enter number of aFiliales H(t) Are all affiliates included? F-]YesFx-]No J Organization type (check only one) u501(c) ( 3 ) Insert no ) u4947(a)(1) or u527 (It 'No' attach a list Sea instructions ) H(d) Is this a separate return filed by an or ani K Check here ,1 organizations gross receipts are normally not mare Nan $25 000 E] Ne The zation covered by a group rulings ~ Yes El No organization need not file a return w+N -

New Actors in the Global Economy

New actors in the global economy Citation for published version (APA): Broich, T. (2017). New actors in the global economy: the case of Chinese development finance in Africa. Boekenplan. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20171213tb Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2017 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20171213tb Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

TV Channel 5-6 Radio Proposal

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Promoting Diversification of Ownership ) MB Docket No 07-294 in the Broadcasting Services ) ) 2006 Quadrennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 06-121 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) 2002 Biennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 02-277 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) Cross-Ownership of Broadcast Stations and ) MM Docket No. 01-235 Newspapers ) ) Rules and Policies Concerning Multiple Ownership ) MM Docket No. 01-317 of Radio Broadcast Stations in Local Markets ) ) Definition of Radio Markets ) MM Docket No. 00-244 ) Ways to Further Section 257 Mandate and To Build ) MB Docket No. 04-228 on Earlier Studies ) To: Office of the Secretary Attention: The Commission BROADCAST MAXIMIZATION COMMITTEE John J. Mullaney Mark Lipp Paul H. Reynolds Bert Goldman Joseph Davis, P.E. Clarence Beverage Laura Mizrahi Lee Reynolds Alex Welsh SUMMARY The Broadcast Maximization Committee (“BMC”), composed of primarily of several consulting engineers and other representatives of the broadcast industry, offers a comprehensive proposal for the use of Channels 5 and 6 in response to the Commission’s solicitation of such plans. BMC proposes to (1) relocate the LPFM service to a portion of this spectrum space; (2) expand the NCE service into the adjacent portion of this band; and (3) provide for the conversion and migration of all AM stations into the remaining portion of the band over an extended period of time and with digital transmissions only. -

BROADCAST MAXIMIZATION COMMITTEE John J. Mullaney

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Promoting Diversification of Ownership ) MB Docket No 07-294 in the Broadcasting Services ) ) 2006 Quadrennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 06-121 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) 2002 Biennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 02-277 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) Cross-Ownership of Broadcast Stations and ) MM Docket No. 01-235 Newspapers ) ) Rules and Policies Concerning Multiple Ownership ) MM Docket No. 01-317 of Radio Broadcast Stations in Local Markets ) ) Definition of Radio Markets ) MM Docket No. 00-244 ) Ways to Further Section 257 Mandate and To Build ) MB Docket No. 04-228 on Earlier Studies ) To: Office of the Secretary Attention: The Commission BROADCAST MAXIMIZATION COMMITTEE John J. Mullaney Mark Lipp Paul H. Reynolds Bert Goldman Joseph Davis, P.E. Clarence Beverage Laura Mizrahi Lee Reynolds Alex Welsh SUMMARY The Broadcast Maximization Committee (“BMC”), composed of primarily of several consulting engineers and other representatives of the broadcast industry, offers a comprehensive proposal for the use of Channels 5 and 6 in response to the Commission’s solicitation of such plans. BMC proposes to (1) relocate the LPFM service to a portion of this spectrum space; (2) expand the NCE service into the adjacent portion of this band; and (3) provide for the conversion and migration of all AM stations into the remaining portion of the band over an extended period of time and with digital transmissions only. -

List of Radio Stations in Massachusetts

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in Massachusetts From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of the FCC-licensed radio stations in the United States Commonwealth of Contents Massachusetts, which can be sorted by their call signs, frequencies, cities of license, licensees, Featured content and programming formats. Current events Random article Call City of License Frequency Licensee [1] Format[citation needed] Donate to Wikipedia sign [1][2] Wikipedia store WAAF 107.3 FM Westborough Entercom License, LLC Active rock Interaction Carter Broadcasting WACE 730 AM Chicopee Christian radio Help Corporation About Wikipedia WACF- Community portal 98.1 FM Brookfield A.P.P.L.E. Seed, Inc. Variety Recent changes LP Contact page Red Wolf Broadcasting WACM 1270 AM Springfield Oldies Tools Corporation What links here WAEM- 94.9 FM Acton Town of Acton, Massachusetts Variety Related changes LP Upload file WAIC 91.9 FM Springfield American International College College radio Special pages open in browser PRO version Are youWAIY- a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Permanent link WAIY- 107.7 FM Belchertown Dwight Chapel Inc. Religious Teaching Page information LP Wikidata item WAMG 890 AM Dedham Gois Broadcasting Boston LLC Spanish Cite this page WAMH 89.3 FM Amherst Trustees of Amherst College College radio Print/export Great Create a book WAMQ 105.1 FM WAMC Public radio Barrington Download as PDF Printable version Saga Communications of New WAQY 102.1 FM Springfield Classic rock England, LLC In other projects Attleboro Access Cable Wikimedia Commons WARA 1320 AM Attleboro Talk/Oldies Systems, Inc. -

Winter 2012 Vol 17 • No

Winter 2012 Vol 17 • No. 4 2012 IN THIS ISSUE say “thank you” for the entry! the for you” “thank say Letter from the Editor FCC Filings Recap to something little a you send even might We newsletters! Airwaves future . We’ll feature some of the best entries in in entries best the of some feature We’ll . to [email protected] Send your station success stories along with any photos you want to share share to want you photos any with along stories success station your Send Community Events Request The following is a listing of the FCC proceedings in which the Massachusetts Broadcasters you! from hear to want We brighter? little a holiday someone’s make Association jointly participated, or plan to participate, during 2012. These examples of advocacy to way original an with up come or need, in families for funds raise Continuing Education FROM THE EDITOR before the FCC well illustrate the vigorous efforts of the MBA to protect and advance the best bank, food local a for food collect team your and you Did community. Reimbursement interests of the free, local, over-the-air, radio and television industries before the FCC. For a your to back give to anything did station your if know to wants complete summary of each filing, head to massbroadcasters.org, move your mouse over the Association Broadcasters Massachusetts the and season, holiday the It’s MBA Sound Bites 2012 “Member” tab and click “FCC Filings.” Request An old lottery slogan says, “All it takes is a AIRWAVES dollar and a dream.” Sound Bites 2012 was by all accounts a huge success. -

Freq Call State Location U D N C Distance Bearing

AM BAND RADIO STATIONS COMPILED FROM FCC CDBS DATABASE AS OF FEB 6, 2012 POWER FREQ CALL STATE LOCATION UDNCDISTANCE BEARING NOTES 540 WASG AL DAPHNE 2500 18 1107 103 540 KRXA CA CARMEL VALLEY 10000 500 848 278 540 KVIP CA REDDING 2500 14 923 295 540 WFLF FL PINE HILLS 50000 46000 1523 102 540 WDAK GA COLUMBUS 4000 37 1241 94 540 KWMT IA FORT DODGE 5000 170 790 51 540 KMLB LA MONROE 5000 1000 838 101 540 WGOP MD POCOMOKE CITY 500 243 1694 75 540 WXYG MN SAUK RAPIDS 250 250 922 39 540 WETC NC WENDELL-ZEBULON 4000 500 1554 81 540 KNMX NM LAS VEGAS 5000 19 67 109 540 WLIE NY ISLIP 2500 219 1812 69 540 WWCS PA CANONSBURG 5000 500 1446 70 540 WYNN SC FLORENCE 250 165 1497 86 540 WKFN TN CLARKSVILLE 4000 54 1056 81 540 KDFT TX FERRIS 1000 248 602 110 540 KYAH UT DELTA 1000 13 415 306 540 WGTH VA RICHLANDS 1000 97 1360 79 540 WAUK WI JACKSON 400 400 1090 56 550 KTZN AK ANCHORAGE 3099 5000 2565 326 550 KFYI AZ PHOENIX 5000 1000 366 243 550 KUZZ CA BAKERSFIELD 5000 5000 709 270 550 KLLV CO BREEN 1799 132 312 550 KRAI CO CRAIG 5000 500 327 348 550 WAYR FL ORANGE PARK 5000 64 1471 98 550 WDUN GA GAINESVILLE 10000 2500 1273 88 550 KMVI HI WAILUKU 5000 3181 265 550 KFRM KS SALINA 5000 109 531 60 550 KTRS MO ST. LOUIS 5000 5000 907 73 550 KBOW MT BUTTE 5000 1000 767 336 550 WIOZ NC PINEHURST 1000 259 1504 84 550 WAME NC STATESVILLE 500 52 1420 82 550 KFYR ND BISMARCK 5000 5000 812 19 550 WGR NY BUFFALO 5000 5000 1533 63 550 WKRC OH CINCINNATI 5000 1000 1214 73 550 KOAC OR CORVALLIS 5000 5000 1071 309 550 WPAB PR PONCE 5000 5000 2712 106 550 WBZS RI -

Broadcast Actions 4/20/2006

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 46218 Broadcast Actions 4/20/2006 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 04/17/2006 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED CT BR-20051121AIY WYBC 72820 YALE BROADCASTING Renewal of License. COMPANY, INC. E 1340 KHZ CT , NEW HAVEN ME BR-20051122ADF WLOB 9202 ATLANTIC COAST RADIO, LLC Renewal of License. E 1310 KHZ ME , PORTLAND CT BR-20051122ADX WCUM 54553 RADIO CUMBRE Renewal of License. BROADCASTING, INC. E 1450 KHZ CT , BRIDGEPORT ME BR-20051130ABR WPHX 74068 FNX BROADCASTING L.L.C. Renewal of License. E 1220 KHZ ME , SANFORD MA BR-20051201AYT WILD 47413 RADIO ONE OF BOSTON Renewal of License. LICENSES, LLC E 1090 KHZ MA , BOSTON Page 1 of 26 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 46218 Broadcast Actions 4/20/2006 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 04/17/2006 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED VT BR-20051201BHM WVNR 52636 PINE TREE BROADCASTING Renewal of License. COMPANY E 1340 KHZ VT , POULTNEY NH BR-20051201BVG WBNC 49203 MT. -

ROBERT W. Mcchesney

ROBERT W. McCHESNEY Curriculum Vitae October 2018 [email protected] Home address: 2118 West Lawn Avenue, Madison WI 53711 Work Address: 3001 Lincoln Hall, Urbana IL 61820 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY PROFILE ............................................................................................... 2-3 A NOTE ON LINKS FORMAT ................................................................................... 3 PROFILES AND PUBLISHED INTERVIEWS .................................................................... 3-14 VIDEO/MOTION PICTURE APPEARANCES.................................................................. 14-15 ACADEMIC POSITIONS ........................................................................................... 14-15 EDUCATION ......................................................................................................... 15 TEACHING EXPERIENCE .......................................................................................... 15-16 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE ................................................................................... 16-30 BOOKS ................................................................................................................ 30-56 EDITED BOOKS ..................................................................................................... 56-59 JOURNAL ARTICLES AND MONOGRAPHS ................................................................... 59-65 BOOK CHAPTERS ................................................................................................. -

Autonomous Robotic Rescue Boat Showing How the Three Main Systems Interact with Each Other

Autonomous Man Overboard Rescue Equipment A Major Qualifying Project Report: Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By ___________________ Frederick Hunter (RBE) ___________________ Thomas Hunter (ME and ECE) Date:_______ Approved: ______________ David Cyganski, Major Advisor _____________________ Ken Stafford, Co-Advisor i Acknowledgements We would like to thank professors Cyganski and Stafford for advising the project. Special thanks to professor Stafford for donating MINI, his inflatable Sea Rogue tender used as the rescue craft in this project. Professor Gennert, for allowing us to borrow the trolling motors from a previous autonomous kayak MQP as well as Alex Kindle and Justin Stoker for their help the documentation they have provided us from a previous version of this project. We would also like to thank our parents for putting up with the circuits and construction taking place on our kitchen table. i Abstract This project addressed the problem of rescuing people who have fallen overboard at sea. Large vessels with slow response times and limited turning capabilities are poorly equipped to handle man overboard cases. To solve this problem, a robotic rescue boat was developed with support from systems for the vessel and victim that autonomously help pilot the rescue boat via GPS, a magnetic compass, and a project-specific terminal location system. The same system also supports the return of the victim to the vessel. ii Executive Summary Ever since man has attempted to travel across the ocean there has been a risk of persons falling overboard. -

PUBLIC VERSION Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES

PUBLIC VERSION Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Washington, D.C. ) IN THE MATTER OF: ) ) ) Docket No. 2005-1 CRB DTRA DIGITAL PERFORMANCE RIGHT . ) IN SOUND RECORDINGS AND . ) EPHEMERAL RECORDINGS ) ) RADIO FINDINGS OFBROADCASTERS'ROPOSED FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW Bruce G. Joseph (D.C. Bar No. 338236) Karyn K. Ablin (D.C. Bar No. 454473) Matthew J. Astle (D.C. Bar No. 488084) WILEY REIN 4 FIELDING LLP 1776 K Street NW Washington, DC 20006 202.719.7258 202.719.7049 (Fax) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Counselfor Bonneville International Corp., Clear Channel Communications Inc.; Nationa/ Religious Broadcasters Music License Committee, and Susquehanna Radio Corp. December 15, 2006 PUBLIC VERSION Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Washington, D.C. Qa IN THE MATTER OF: S~ Docket No. 2005-1 CRB DTRA DIGITAL PERFORMANCE RIGHT +a IN SOUND RECORDINGS AND EPHEMERAL RECORDINGS (oO RADIO FINDINGS OFBROADCASTERS'ROPOSED FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW Bruce G. Joseph (D.C. Bar No. 338236) Karyn K. Ablin (D.C. Bar No. 454473) Matthew J. Astle (D.C. Bar No. 488084) WILEY REIN 8'c FIELDING LLP 1776 K Street NW Washington, DC 20006 202.719.7258 202.719.7049 (Fax) bjosephlwrf.corn [email protected] [email protected] Counselfor Bonneville International Corp., Clear Channel Communications, Inc.; National Religious Broadcasters Music License Committee, and Susquehanna Radio Corp. December 15, 2006 PUBLIC VERSION TABLE OF CONTENTS P~ae PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT. I. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW. II. RADIO BROADCASTERS AND AM/FM STREAMING. III. HISTORY OF RADIO'S RELATIONSHIP WITH THE SOUND RECORDING PERFORMANCE RIGHT A.