New Actors in the Global Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethiopia Briefing Packet

ETHIOPIA PROVIDING COMMUNITY HEALTH TO POPULATIONS MOST IN NEED se P RE-FIELD BRIEFING PACKET ETHIOPIA 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org ETHIOPIA Country Briefing Packet Contents ABOUT THIS PACKET 3 BACKGROUND 4 EXTENDING YOUR STAY 5 PUBLIC HEALTH OVERVIEW 7 Health Infrastructure 7 Water Supply and sanitation 9 Health Status 10 FLAG 12 COUNTRY OVERVIEW 13 General overview 13 Climate and Weather 13 Geography 14 History 15 Demographics 21 Economy 22 Education 23 Culture 25 Poverty 26 SURVIVAL GUIDE 29 Etiquette 29 LANGUAGE 31 USEFUL PHRASES 32 SAFETY 35 CURRENCY 36 CURRENT CONVERSATION RATE OF 24 MAY, 2016 37 IMR RECOMMENDATIONS ON PERSONAL FUNDS 38 TIME IN ETHIOPIA 38 EMBASSY INFORMATION 39 WEBSITES 40 !2 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org ETHIOPIA Country Briefing Packet ABOUT THIS PACKET This packet has been created to serve as a resource for the 2016 ETHIOPIA Medical Team. This packet is information about the country and can be read at your leisure or on the airplane. The final section of this booklet is specific to the areas we will be working near (however, not the actual clinic locations) and contains information you may want to know before the trip. The contents herein are not for distributional purposes and are intended for the use of the team and their families. Sources of the information all come from public record and documentation. You may access any of the information and more updates directly from the World Wide Web and other public sources. -

The Golden Gospels and Chronicle of Aksum at Aksum Seyon’S Church: the Photographs Taken by Theodor V

The Golden Gospels and Chronicle of Aksum at Aksum Seyon’s Church: The photographs taken by Theodor v. Lüpke (1906) Anaïs Wion To cite this version: Anaïs Wion. The Golden Gospels and Chronicle of Aksum at Aksum Seyon’s Church: The pho- tographs taken by Theodor v. Lüpke (1906). Steffen Wenig. IN KAISERLICHEM AUFTRAG. Die Deutsche Aksum-Expedition 1906 unter Enno Littmann, Ethnographische, kirchenhistorische und archäologisch-historische Untersuchungen (3), Reichert Verlag, pp.117-133, 2017, 978-3-89500-891-7. halshs-01525075 HAL Id: halshs-01525075 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01525075 Submitted on 21 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Anaïs Wion The Golden Gospels and Chronicle of Aksum at Aksum Seyon’s Church: The photographs taken by Theodor v. Lüpke (1906)* Enno Littmann had a great interest in Ethio- the DAE took photographs closer up of regalia pian literature, both written and oral: while from the church, including the codices (Figs. 2 in Ethiopia, he collected 149 codices and 167 and 3).4 The next day, Littmann and v. Lüpke scrolls and he also transcribed and translated returned to the church and asked for permission numerous oral traditions.1 In parallel, members to take pictures of the two Golden Gospels and of the DAE – especially Theodor v. -

Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid This Page Intentionally Left Blank Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid

‘Th ank God for great journalism. Th is book is a much needed, ex- haustively researched and eff ortlessly well written recent history of Ethiopia. A book that strips away the cant and rumour, the pros and antis and thoroughly explains the people, politics and economics of that most beautiful nation. A superb and vital piece of work by some- one who clearly loves the country of which he writes.’ Bob Geldof ‘Th e great Ethiopian famine changed everything and nothing. It fun- damentally altered the rich world’s sense of its responsibility to the hungry and the poor, but didn’t solve anything. A quarter of a century on, we’re still arguing about the roots of the problem, let alone the so- lution, and—though there has been progress—Ethiopia’s food inse- curity gets worse, not better. Peter Gill was one of the most thorough and eff ective television journalists of his generation. He was there in 1984 and his work at the time added up to the most sensible, balanced and comprehensive explanation of what had happened. Twenty-fi ve years later, he’s gone back to test decades of aspiration against the re- alities on the ground. It’s a book that bridges journalism and history, judicious analysis with a strong, and often gripping, narrative. Always readable, but never glib, this is a must for all those who think there is a simple answer to the famine, still waiting in the wings. ’ Michael Buerk ‘No outsider understands Ethiopia better than Peter Gill. He com- bines compassion with a clinical commitment to the truth. -

Daytime Bandscans

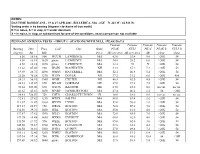

NOTES: DAYTIME BANDSCANS - 19 & 27 APR 2001 -BILLERICA, MA - (GC= 71.221 W / 42.533 N) Sorting order is by bearing (degrees clockwise of true north) N = in noise, S = in slop, U = under dominant X = in noise, in slop, or subdominant for one of the conditions, exact comparison not available PENNANT ANTENNA TESTS - GROUP 1 - STATIONS WITH NULL / PEAK DATA Pennant Pennant Pennant Pennant Pennant Bearing Dist. Freq. Call City State/ PEAK NULL PK-N PEAK R NULL R degrees km kHz Prov. dB over zero dB over zero dB ohms ohms 8.56 16.18 800 WCCM LAWRENCE MA 63.0 53.4 9.6 >20K 54 8.56 16.18 1620 pirate LAWRENCE MA 34.8 28.2 6.6 >20K 54 8.56 16.18 1670 pirate LAWRENCE MA 22.8 N X >20K 54 14.62 87.04 930 WGIN ROCHESTER NH 44.4 37.2 7.2 >20K 54 19.89 28.72 1490 WHAV HAVERHILL MA 52.2 46.8 5.4 >20K 54 22.20 78.58 1270 WTSN DOVER NH 37.2 31.2 6.0 >20K 486 24.21 56.10 1540 WGIP EXETER NH 46.8 42.0 4.8 >20K 54 24.81 139.07 870 WLAM GORHAM ME 27.0 19.2 7.8 >20K 54 36.61 322.00 620 WZON BANGOR ME 24.0 24.0 0.0 no var. no var. 41.83 43.83 1450 WNBP NEWBURYPORT MA 47.4 46.2 1.2 54 >20K 54.81 758.59 720 CHTN CHARLOTTETOWN PI 18.0 18.0 0.0 no var. -

History of Events and Internal Developement. the Example of The

Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies University of Addis Ababa, 1984 Edited by Dr Taddese Beyene Volume 1 isbn — Volume 1: 1 85450 000 7 Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa 1988 Table of Contents Preface Opening Address The New Ethiopia: Major Defining Characteristics. Research Trends in Ethiopian Studies at Addis Ababa University over the last Twenty-Five Years. Prehistory and Archaeology Early Stone Age Cultures in Ethiopia. Alemseged Abbay Les Monuments Gondariens des XVIIe et XVIIIe Steeles. Une Vue d'ensemble. Francis Anfray Le Gisement Paleolithique de Melka-Kunture. Evolution et Culture. Jean Chavaillon A Review of the Archaeological Evidence for the Origins of Food Production in Ethiopia. John Desmond Clark Reflections on the Origins of the Ethiopian Civilization. Ephraim Isaac and Cain Felder Remarks on the Late Prehistory and Early History of Northern Ethiopia. Rodolfo Fattovich History to 1800 Is Näwa Bäg'u an Ethiopian Cross? Ewa Balicka-Witakowska The Ruins of Mertola-Maryam. Stephen Bell Who Wrote "The History of King Sarsa Dengel" - Was it the Monk Bahrey? S. B. Chernetsov Les Affluents de la Rive Droite du Nil dans la Geographie Antique. Jehan Desanges Ethiopian Attitudes towards Europeans until 1750. Franz Amadeus Dombrowski The Ta'ämra 'Iyasus: a study of textual and source-critical problems. S. Gem The Mediterranean Context for the Medieval Rock-Cut Churches of Ethiopia. Michael Gerven Introducing an Arabic Hagiography from Wällo Hussein Ahmed Some Hebrew Sources on the Beta-Israel (Falasha). Steven Kaplan The Problem of the Formation of the Peasant Class in Ethiopia. Yu. M. Kobischanov The Sor'ata Gabr - a Mirror View of Daily Life at the Ethiopian Royal Court in the Middle Ages. -

The Ethiopian State: Perennial Challenges in the Struggle for Development

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College International Studies Honors Projects International Studies Department 4-26-2016 The thiopiE an State: Perennial Challenges in the Struggle for Development Hawi Tilahune Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tilahune, Hawi, "The thiopE ian State: Perennial Challenges in the Struggle for Development" (2016). International Studies Honors Projects. Paper 21. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors/21 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the International Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Studies Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ethiopian State: Perennial Challenges in the Struggle for Development Hawi Tilahune Presented to the Department of International Studies, Macalester College. Faculty Advisors: Dr. Ahmed I. Samatar and Professor David Blaney 4/26/2016 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 3 ABSTRACT 4 CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 6 I. THE CHALLENGE 6 II. RESEARCH QUESTIONS 7 III. MOTIVATION 8 IV. SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY 10 V. PREPARATION 10 VI. ORGANIZATION 12 CHAPTER II: LITERATURE REVIEW 15 I. THE STATE 15 II. NATIONHOOD AND NATIONALISM 30 III. WORLD ORDER 37 IV. DEVELOPMENT 43 CHAPTER III: BASIC INFORMATION 50 I. PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY 50 II. POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY 51 III. SOCIAL GEOGRAPHY 51 IV. ECONOMY 52 CHAPTER IV: EMPEROR MENELIK II (1889-1913) 54 I. INTRODUCTION 54 II. EUROPEAN IMPERIALISM IN THE HORN 55 III. TERRITORIAL AND CULTURAL EXPANSION 58 IV. -

Sabla Wangêl, the Queen of the Kingdom of Heaven Margaux Herman

Sabla Wangêl, the queen of the Kingdom of Heaven Margaux Herman To cite this version: Margaux Herman. Sabla Wangêl, the queen of the Kingdom of Heaven. Addis Ababa University Institute of Ethiopian Studies XVII International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, Nov 2009, ADDIS ABEBA, France. halshs-00699633 HAL Id: halshs-00699633 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00699633 Submitted on 21 May 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Herman Margaux, (Phd Candidate) University of Paris1-La Sorbonne - Department of History Cemaf-Paris UMR 8171 Supervisor : Bertrand Hirsch Current Mailing Address: Herman Margaux 12-14 bd-Richard Lenoir 75011 Paris- France e-mail:[email protected] 1 Säblä Wängel, the Queen of the Kingdom of Heaven Starting from a general consideration about the Ethiopian queens from 16th to 18th centuries, I have come to focus on Queen Säblä Wängel, a notable figure of the royalty of the 16th century, and on her royal foundation called Mängəśtä Sämayat Kidanä Məhrät. This paper is based on an analysis of a corpus of composite sources. We will compare the statements explaining the history of the construction of the church in the sources written after the death of the queen to the records produced when she was alive. -

Book Chapter

Book Chapter Childhood Portraits of Iyasu: the Creation of the Heir through Images SOHIER, Estelle Reference SOHIER, Estelle. Childhood Portraits of Iyasu: the Creation of the Heir through Images. In: Ficquet, E. & Smidt W. The Life and Times of Lij Iyasu: New Insights. Zürich, Berlin : Lit Verlag, 2014. p. 51-74 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:34517 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Off-Print of: SOHIER, Estelle, “Childhood Portraits of Iyasu: the Creation of the Heir through Images.” In Éloi Ficquet and Wolbert G.C. Smidt, eds, The Life and Times of Lïj Iyasu of Ethiopia. New Insights. Zürich, Berlin: LIT Vlg, 2014, pp. 51-74 The Life and Times of Lïj Iyasu of Ethiopia New Insights edited by Éloi Ficquet and Wolbert G.C. Smidt __________ LIT Table of Contents List of Figures and Pictures, pp. vii-ix Note on the transliteration, pp. xi Map of Ethiopia under Lïj Iyasu, ca. 1909 – 1921, p. xiii. Foreword Éloi Ficquet & Wolbert G.C. Smidt, pp. 1-2 Part I: The Background: Family, Marriages and Alleged Origins Understanding Lïj Iyasu through his Forefathers: The Mammedoch Imam-s of Wello Eloi Ficquet, pp. 5-29. Some Observations on a Sharifian Genealogy of Lïj Iyasu (Vatican Arabic Ms. 1796) Alessandro Gori, pp. 31-38. Lïj Iyasu’s Marriages as a Reflection of his Domestic Policy Zuzanna Augustyniak, pp. 39-47. Part II: The Heir: Between Ethnic and Religious Pluralism, Reform and Continuity Childhood Portraits of Iyasu: the Creation of the Heir through Images Estelle Sohier, pp. -

Medieval Ethiopian Diplomacy with Latin Europe — Medieval Ethiopian Kingship

Verena Krebs | Ethiopian Medieval Diplomacy & Kingship Medieval Ethiopian Diplomacy with Latin Europe — Medieval Ethiopian Kingship Verena Krebs Historical Institute Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany Verena Krebs | Ethiopian Medieval Diplomacy & Kingship Solomonic Royal Churches and Monasteries built between ca. 1400 and 1540, (i.e. the reign of aṣe Dawit and aṣe Lǝbnä Dǝngǝl) built by Solomonic Kings aṣe Dawit —1 aṣe Yǝsḥaq —3 aṣe Täklä Maryam —1 aṣe Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob —9 aṣe Bäʾǝdä Maryam —4 aṣe Ǝskǝndǝr —4 aṣe Naʿod —2 aṣe Lǝbnä Dǝngǝl —4 built by Royal Women Ǝleni —1 Romna —1 Naʿod Mogäsa —3 Verena Krebs | Ethiopian Medieval Diplomacy & Kingship Verena Krebs | Ethiopian Medieval Diplomacy & Kingship Early Solomonic rulers…. Yəkunno Amlak Wədəm Räʿad Säyfä Arʿad Yǝsḥaq Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob Ǝskǝndǝr Ǝleni – Lǝbnä Dǝngǝl 1270–1285 1299–1314 1344–1371 1414–1429/30 1434–1464 1478–1494 1508–1540 Yagba Ṣəyon ʿAmdä Ṣəyon I Dawit II Täklä Maryam Bäʾǝdä Maryam Naʿod 1285–94 1314-1344 1378/79–1412 1430–1433 1468–1478 1494–1508 …who sent (formal/informal) delegations to Latin Europe Verena Krebs | Ethiopian Medieval Diplomacy & Kingship Renato Lefèvre, 1967 aṣe Dawit’s 1402 mission to Venice caused by a desire to obtain ‘masters of art and industry that could raise the civil and technical level of the Ethiopian state, and therefore strengthen its military efficiency’ Taddesse Tamrat, 1972 aṣe Yǝsḥaq and aṣe Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob sent embassies ‘to Europe asking for technical aid’, ‘the purpose of the delegations sent out to Europe was to ask for more artisans and military experts’. ‘The Ethiopians had always been impressed by the political and military aspects of an all-over Christian solidarity against the Muslim powers of the Near East’ and wanted to share ‘in the superior technical advancement of European nations’. -

Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on the Ethiopian Economy

Ethiopian Economics Association (EEA) and Ethiopian Strategy Support Program (ESSP) of IFPRI PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIFTEENTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON THE ETHIOPIAN ECONOMY Edited by Amin Abdella Demirew Getachew Gasahw Desalegn Kumadebis Tamiru Samuel Gebreselassie Volume I i Published: June 2018 © Ethiopian Economics Association (EEA) All rights reserved ISBN – 978-99944-54-64-8 Partners of all activities of EEA are the African Capacity Building Foundation (ACBF), the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung of Germany (FES), Think Tank Initiative of the International Development Research Center (IDRC) of Canada, and Civil Society Support Program (CSSP). The 15th International Conference was Co-organized by the Ethiopian Strategy Support Program (ESSP) of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). The 15th International Conference Sponsored by Sponsored by IFPRI, EDRI, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung of Germany, UNECA, UNDP, International Growth Center (IGC), USAID, AKLDP Ethiopia, The World Bank, European Union, PRB, ILRI, CGIAR UF/IFAS. ii FOREWORD The Ethiopian Economics Association (EEA) is happy to issue two volumes of the proceedings of the 15th International Conference (the 26th Annual Conference) on the Ethiopian Economy that was held from July 20 – 22, 2017 at EEA Multi-purpose Building Conference Hall. EEA has been organizing annual conferences on the Ethiopian Economy every year as part of its overall objectives of promoting the development of economics profession in Ethiopia and contributing to the policy formulation and implementation process of our country through research, training, public dialogue forums and publications and dissemination activities. EEA had launched its international conference series in June 2003, after organizing 11 annual national conferences. This series has proved to be an excellent forum at which not only resident Ethiopian researchers, but also Ethiopian researchers based abroad as well as non-Ethiopian researchers throughout the world conducting research on Ethiopia, or more widely, present and discuss research findings. -

Food and Agriculture in Ethiopia

“ Food and Agriculture in Ethiopia and Agriculture Food Paul Dorosh and Shahidur Rashid Editors Dorosh • PROGRESS AND Rashid Food POLICY CHALLENGES Editors and Agriculture in Ethiopia Food and Agriculture in Ethiopia This book is published by the University of Pennsylvania Press (UPP) on behalf of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) as part of a joint-publication series. Books in the series pre- sent research on food security and economic development with the aim of reducing poverty and eliminating hunger and malnutrition in developing nations. They are the product of peer-reviewed IFPRI research and are selected by mutual agreement between the parties for publication under the joint IFPRI-UPP imprint. Food and Agriculture in Ethiopia Progress and Policy Challenges EDITED BY PAUL A. DOROSH AND SHAHIDUR RASHID Published for the International Food Policy Research Institute University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia Copyright © 2012 International Food Policy Research Institute All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112 www.upenn.edu/pennpress Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data CIP DATA TO COME Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables ix List of Boxes xv Foreword xvii Acknowledgments xix Acronyms and Abbreviations xxiii Glossary xxvii 1 Introduction 1 PAUL DOROSH AND SHAHIDUR RASHID PART I Overview and Analysis of Ethiopia’s Food Economy 2 Ethiopian Agriculture: A Dynamic Geographic Perspective 21 JORDAN CHAMBERLIN AND EMILY SCHMIDT 3 Crop Production in Ethiopia: Regional Patterns and Trends 53 ALEMAYEHU SEYOUM TAFFESSE, PAUL DOROSH, AND SINAFIKEH ASRAT GEMESSA 4 Seed, Fertilizer, and Agricultural Extension in Ethiopia 84 DAVID J. -

The History of World Civilization. 3 Cyclus (1450-2070) New Time ("New Antiquity"), Capitalism ("New Slaveownership"), Upper Mental (Causal) Plan

The history of world civilization. 3 cyclus (1450-2070) New time ("new antiquity"), capitalism ("new slaveownership"), upper mental (causal) plan. 19. 1450-1700 -"neoarchaics". 20. 1700-1790 -"neoclassics". 21. 1790-1830 -"romanticism". 22. 1830-1870 – «liberalism». Modern time (lower intuitive plan) 23. 1870-1910 – «imperialism». 24. 1910-1950 – «militarism». 25.1950-1990 – «social-imperialism». 26.1990-2030 – «neoliberalism». 27. 2030-2070 – «neoromanticism». New history. We understand the new history generally in the same way as the representatives of Marxist history. It is a history of establishment of new social-economic formation – capitalism, which, in difference to the previous formations, uses the economic impelling and the big machine production. The most important classes are bourgeoisie and hired workers, in the last time the number of the employees in the sphere of service increases. The peasants decrease in number, the movement of peasants into towns takes place; the remaining peasants become the independent farmers, who are involved into the ware and money economy. In the political sphere it is an epoch of establishment of the republican system, which is profitable first of all for the bourgeoisie, with the time the political rights and liberties are extended for all the population. In the spiritual plan it is an epoch of the upper mental, or causal (later lower intuitive) plan, the humans discover the laws of development of the world and man, the traditional explanations of religion already do not suffice. The time of the swift development of technique (Satan was loosed out of his prison, according to Revelation 20.7), which causes finally the global ecological problems.