The Ethiopian State: Perennial Challenges in the Struggle for Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local History of Ethiopia an - Arfits © Bernhard Lindahl (2005)

Local History of Ethiopia An - Arfits © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) an (Som) I, me; aan (Som) milk; damer, dameer (Som) donkey JDD19 An Damer (area) 08/43 [WO] Ana, name of a group of Oromo known in the 17th century; ana (O) patrikin, relatives on father's side; dadi (O) 1. patience; 2. chances for success; daddi (western O) porcupine, Hystrix cristata JBS56 Ana Dadis (area) 04/43 [WO] anaale: aana eela (O) overseer of a well JEP98 Anaale (waterhole) 13/41 [MS WO] anab (Arabic) grape HEM71 Anaba Behistan 12°28'/39°26' 2700 m 12/39 [Gz] ?? Anabe (Zigba forest in southern Wello) ../.. [20] "In southern Wello, there are still a few areas where indigenous trees survive in pockets of remaining forests. -- A highlight of our trip was a visit to Anabe, one of the few forests of Podocarpus, locally known as Zegba, remaining in southern Wello. -- Professor Bahru notes that Anabe was 'discovered' relatively recently, in 1978, when a forester was looking for a nursery site. In imperial days the area fell under the category of balabbat land before it was converted into a madbet of the Crown Prince. After its 'discovery' it was declared a protected forest. Anabe is some 30 kms to the west of the town of Gerba, which is on the Kombolcha-Bati road. Until recently the rough road from Gerba was completed only up to the market town of Adame, from which it took three hours' walk to the forest. A road built by local people -- with European Union funding now makes the forest accessible in a four-wheel drive vehicle. -

Red Terror NEVER AGAIN

Praise for books by Nobel Peace Prize finalist R. J. Rummel "26th in a Random House poll on the best nonfiction book of the 20th Century" Random House (Modern Library) “. the most important . in the history of international relations.” John Norton Moore Professor of Law and Director, Center for National Security Law, former Chairman of the Board of Directors of the U. S. Institute of Peace “. among the most exciting . in years.” Jim Powell “. most comprehensive . I have ever encountered . illuminating . .” Storm Russell “One more home run . .” Bruce Russett, Professor of International Relations “. has profoundly affected my political and social views.” Lurner B Williams “. truly brilliant . ought to be mandatory reading.” Robert F. Turner, Professor of Law, former President of U.S. Institute of Peace ". highly recommend . ." Cutting Edge “We all walk a little taller by climbing on the shoulders of Rummel’s work.” Irving Louis Horowitz, Professor Of Sociology. ". everyone in leadership should read and understand . ." DivinePrinciple.com “. .exciting . pushes aside all the theories, propaganda, and wishful thinking . .” www.alphane.com “. world's foremost authority on the phenomenon of ‘democide.’” American Opinion Publishing “. excellent . .” Brian Carnell “. bound to be become a standard work . .” James Lee Ray, Professor of Political Science “. major intellectual accomplishment . .will be cited far into the next century” Jack Vincent, Professor of Political Science.” “. most important . required reading . .” thewizardofuz (Amazon.com) “. valuable perspective . .” R.W. Rasband “ . offers a desperately needed perspective . .” Andrew Johnstone “. eloquent . very important . .” Doug Vaughn “. should be required reading . .shocking and sobering . .” Sugi Sorensen NEVER AGAIN Book 4 Red Terror NEVER AGAIN R.J. -

Ethiopia Briefing Packet

ETHIOPIA PROVIDING COMMUNITY HEALTH TO POPULATIONS MOST IN NEED se P RE-FIELD BRIEFING PACKET ETHIOPIA 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org ETHIOPIA Country Briefing Packet Contents ABOUT THIS PACKET 3 BACKGROUND 4 EXTENDING YOUR STAY 5 PUBLIC HEALTH OVERVIEW 7 Health Infrastructure 7 Water Supply and sanitation 9 Health Status 10 FLAG 12 COUNTRY OVERVIEW 13 General overview 13 Climate and Weather 13 Geography 14 History 15 Demographics 21 Economy 22 Education 23 Culture 25 Poverty 26 SURVIVAL GUIDE 29 Etiquette 29 LANGUAGE 31 USEFUL PHRASES 32 SAFETY 35 CURRENCY 36 CURRENT CONVERSATION RATE OF 24 MAY, 2016 37 IMR RECOMMENDATIONS ON PERSONAL FUNDS 38 TIME IN ETHIOPIA 38 EMBASSY INFORMATION 39 WEBSITES 40 !2 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org ETHIOPIA Country Briefing Packet ABOUT THIS PACKET This packet has been created to serve as a resource for the 2016 ETHIOPIA Medical Team. This packet is information about the country and can be read at your leisure or on the airplane. The final section of this booklet is specific to the areas we will be working near (however, not the actual clinic locations) and contains information you may want to know before the trip. The contents herein are not for distributional purposes and are intended for the use of the team and their families. Sources of the information all come from public record and documentation. You may access any of the information and more updates directly from the World Wide Web and other public sources. -

Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism

Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review 51 | 2016 Global History, East Africa and The Classical Traditions Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism Phiroze Vasunia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/314 Publisher IFRA - Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2016 Number of pages: 21-43 ISSN: 2071-7245 Electronic reference Phiroze Vasunia, « Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism », Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review [Online], 51 | 2016, Online since 07 May 2019, connection on 08 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/314 Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review Global History, East Africa and the Classical Traditions. Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism Phiroze Vasunia Can the Ethiopian change his skinne? or the leopard his spots? Jeremiah 13.23, in the King James Version (1611) May a man of Inde chaunge his skinne, and the cat of the mountayne her spottes? Jeremiah 13.23, in the Bishops’ Bible (1568) I once encountered in Sicily an interesting parallel to the ancient confusion between Indians and Ethiopians, between east and south. A colleague and I had spent some pleasant moments with the local custodian of an archaeological site. Finally the Sicilian’s curiosity prompted him to inquire of me “Are you Chinese?” Frank M. Snowden, Blacks in Antiquity (1970) The ancient confusion between Ethiopia and India persists into the late European Enlightenment. Instances of the confusion can be found in the writings of distinguished Orientalists such as William Jones and also of a number of other Europeans now less well known and less highly regarded. -

Managing Ethiopia's Transition

Managing Ethiopia’s Unsettled Transition $IULFD5HSRUW1 _ )HEUXDU\ +HDGTXDUWHUV ,QWHUQDWLRQDO&ULVLV*URXS $YHQXH/RXLVH %UXVVHOV%HOJLXP 7HO )D[ EUXVVHOV#FULVLVJURXSRUJ Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Anatomy of a Crisis ........................................................................................................... 2 A. Popular Protests and Communal Clashes ................................................................. 3 B. The EPRDF’s Internal Fissures ................................................................................. 6 C. Economic Change and Social Malaise ....................................................................... 8 III. Abiy Ahmed Takes the Reins ............................................................................................ 12 A. A Wider Political Crisis .............................................................................................. 12 B. Abiy’s High-octane Ten Months ................................................................................ 15 IV. Internal Challenges and Opportunities ............................................................................ 21 A. Calming Ethnic and Communal Conflict .................................................................. -

519 Ethiopia Report With

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Ethiopia: A New Start? T • ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY KJETIL TRONVOLL ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully © Minority Rights Group 2000 acknowledges the support of Bilance, Community Aid All rights reserved Abroad, Dan Church Aid, Government of Norway, ICCO Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- and all other organizations and individuals who gave commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- financial and other assistance for this Report. mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. For further information please contact MRG. This Report has been commissioned and is published by A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the ISBN 1 897 693 33 8 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the ISSN 0305 6252 author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in Published April 2000 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. Typset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR KJETIL TRONVOLL is a Research Fellow and Horn of Ethiopian elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1994, Africa Programme Director at the Norwegian Institute of and the Federal and Regional Assemblies in 1995. -

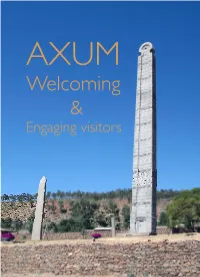

AXUM – Welcoming and Engaging Visitors – Design Report

Pedro Guedes (2010) AXUM – Welcoming and engaging visitors – Design report CONTENTS: Design report 1 Appendix – A 25 Further thoughts on Interpretation Centres Appendix – B 27 Axum signage and paving Presented to Tigray Government and tourism commission officials and stakeholders in Axum in November 2009. NATURE OF SUBMISSION: Design Research This Design report records a creative design approach together with the development of original ideas resulting in an integrated proposal for presenting Axum’s rich tangible and intangible heritage to visitors to this important World Heritage Town. This innovative proposal seeks to use local resources and skills to create a distinct and memorable experience for visitors to Axum. It relies on engaging members of the local community to manage and ‘own’ the various ‘attractions’ for visitors, hopefully keeping a substantial proportion of earnings from tourism in the local community. The proposal combines attitudes to Design with fresh approaches to curatorship that can be applied to other sites. In this study, propositions are tested in several schemes relating to the design of ‘Interpretation centres’ and ideas for exhibits that would bring them to life and engage visitors. ABSTRACT: Axum, in the highlands of Ethiopia was the centre of an important trading empire, controlling the Red Sea and channeling exotic African merchandise into markets of the East and West. In the fourth century (AD), it became one of the first states to adopt Christianity as a state religion. Axum became the major religious centre for the Ethiopian Coptic Church. Axum’s most spectacular archaeological remains are the large carved monoliths – stelae that are concentrated in the Stelae Park opposite the Cathedral precinct. -

Reconstructing Zagwe Civilization

Cultural and Religious Studies, November 2016, Vol. 4, No. 11, 655-667 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2016.11.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reconstructing Zagwe Civilization Melakneh Mengistu Addis Abnaba University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia The Zagwe period is believed to be the richest and most artistic period of Ethiopian civilization since the conversion of Ezana though its achievements have been virtually consigned to obscurity. One of the ideological weapons which aggravated this obscurity is arguably the deep-rooted allegiance of the Kəbrȁ Nȁgȁśt to the Solomonic dynasty. Contemporary researchers on Kəbrȁ Nȁgȁśt seem to have underestimated the ideological onslaught of the Kəbrȁ Nȁgȁśt on the Zagwe period that their contributions to the medieval Ethiopian civilization have been virtually shrouded in mystery. Thus, expatriate and compatriot authorities on the medieval Ethiopian cultural history are called upon to revisit the impacts of the Kəbrȁ Nȁgȁśt on the Zagwe period from the other end of the telescope, thereby, to reconstruct the unsung achievements of Agȁw civilization. Keywords: Kəbrȁ Nȁgȁśt Agäw civilization, obscurity, research gaps, historical reconstruction The Historical Background of Agäws Northern, central and north-western Ethiopia is today inhabited by the Amhara, the Tigre and the Agȁw people, who are hardly distinguishable from one another. These groups have many common cultural, historical, geographical roots and somatic characteristics (Gamst, 1984, pp. 11-12). Agäw is a generic name with which four well-known Cushitic speaking groups of Ethiopia spread over Eritrea and North-western Ethiopia are designated. They are the most ancient and indigenous people of Ethiopia. “The Agäw, indeed, were the very basis on which the whole edifice of Aksumite civilization was constructed. -

From Falashas to Ethiopian Jews

FROM FALASHAS TO ETHIOPIAN JEWS: THE EXTERNAL INFLUENCES FOR CHANGE C. 1860-1960 BY DANIEL P. SUMMERFIELD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON (SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES) FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PhD) 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673074 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673074 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The arrival of a Protestant mission in Ethiopia during the 1850s marks a turning point in the history of the Falashas. Up until this point, they lived relatively isolated in the country, unaffected and unaware of the existence of world Jewry. Following this period and especially from the beginning of the twentieth century, the attention of certain Jewish individuals and organisations was drawn to the Falashas. This contact initiated a period of external interference which would ultimately transform the Falashas, an Ethiopian phenomenon, into Ethiopian Jews, whose culture, religion and identity became increasingly connected with that of world Jewry. It is the purpose of this thesis to examine the external influences that implemented and continued the process of transformation in Falasha society which culminated in their eventual emigration to Israel. -

Sabla Wangêl, the Queen of the Kingdom of Heaven Margaux Herman

Sabla Wangêl, the queen of the Kingdom of Heaven Margaux Herman To cite this version: Margaux Herman. Sabla Wangêl, the queen of the Kingdom of Heaven. Addis Ababa University Institute of Ethiopian Studies XVII International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, Nov 2009, ADDIS ABEBA, France. halshs-00699633 HAL Id: halshs-00699633 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00699633 Submitted on 21 May 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Herman Margaux, (Phd Candidate) University of Paris1-La Sorbonne - Department of History Cemaf-Paris UMR 8171 Supervisor : Bertrand Hirsch Current Mailing Address: Herman Margaux 12-14 bd-Richard Lenoir 75011 Paris- France e-mail:[email protected] 1 Säblä Wängel, the Queen of the Kingdom of Heaven Starting from a general consideration about the Ethiopian queens from 16th to 18th centuries, I have come to focus on Queen Säblä Wängel, a notable figure of the royalty of the 16th century, and on her royal foundation called Mängəśtä Sämayat Kidanä Məhrät. This paper is based on an analysis of a corpus of composite sources. We will compare the statements explaining the history of the construction of the church in the sources written after the death of the queen to the records produced when she was alive. -

Book Chapter

Book Chapter Childhood Portraits of Iyasu: the Creation of the Heir through Images SOHIER, Estelle Reference SOHIER, Estelle. Childhood Portraits of Iyasu: the Creation of the Heir through Images. In: Ficquet, E. & Smidt W. The Life and Times of Lij Iyasu: New Insights. Zürich, Berlin : Lit Verlag, 2014. p. 51-74 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:34517 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Off-Print of: SOHIER, Estelle, “Childhood Portraits of Iyasu: the Creation of the Heir through Images.” In Éloi Ficquet and Wolbert G.C. Smidt, eds, The Life and Times of Lïj Iyasu of Ethiopia. New Insights. Zürich, Berlin: LIT Vlg, 2014, pp. 51-74 The Life and Times of Lïj Iyasu of Ethiopia New Insights edited by Éloi Ficquet and Wolbert G.C. Smidt __________ LIT Table of Contents List of Figures and Pictures, pp. vii-ix Note on the transliteration, pp. xi Map of Ethiopia under Lïj Iyasu, ca. 1909 – 1921, p. xiii. Foreword Éloi Ficquet & Wolbert G.C. Smidt, pp. 1-2 Part I: The Background: Family, Marriages and Alleged Origins Understanding Lïj Iyasu through his Forefathers: The Mammedoch Imam-s of Wello Eloi Ficquet, pp. 5-29. Some Observations on a Sharifian Genealogy of Lïj Iyasu (Vatican Arabic Ms. 1796) Alessandro Gori, pp. 31-38. Lïj Iyasu’s Marriages as a Reflection of his Domestic Policy Zuzanna Augustyniak, pp. 39-47. Part II: The Heir: Between Ethnic and Religious Pluralism, Reform and Continuity Childhood Portraits of Iyasu: the Creation of the Heir through Images Estelle Sohier, pp. -

Abbysinia/Ethiopia: State Formation and National State-Building Project

Abbysinia/Ethiopia: State Formation and National State-Building Project Comparative Approach Daniel Gemtessa Oct, 2014 Department of Political Sience University of Oslo TABLE OF CONTENTS No.s Pages Part I 1 1 Chapter I Introduction 1 1.1 Problem Presentation – Ethiopia 1 1.2 Concept Clarification 3 1.2.1 Ethiopia 3 1.2.2 Abyssinia Functional Differentiation 4 1.2.3 Religion 6 1.2.4 Language 6 1.2.5 Economic Foundation 6 1.2.6 Law and Culture 7 1.2.7 End of Zemanamesafint (Era of the Princes) 8 1.2.8 Oromos, Functional Differentiation 9 1.2.9 Religion and Culture 10 1.2.10 Law 10 1.2.11 Economy 10 1.3 Method and Evaluation of Data Materials 11 1.4 Evaluation of Data Materials 13 1.4.1 Observation 13 1.4.2 Copyright Provision 13 1.4.3 Interpretation 14 1.4.4 Usability, Usefulness, Fitness 14 1.4.5 The Layout of This Work 14 Chapter II Theoretical Background 15 2.1 Introduction 15 2.2 A Short Presentation of Rokkan’s Model as a Point of Departure for 17 the Overall Problem Presentation 2.3 Theoretical Analysis in Four Chapters 18 2.3.1 Territorial Control 18 2.3.2 Cultural Standardization 18 2.3.3 Political Participation 19 2.3.4 Redistribution 19 2.3.5 Summary of the Theory 19 Part II State Formation 20 Chapter III 3 Phase I: Penetration or State Formation Process 20 3.0.1 First: A Short Definition of Nation 20 3.0.2 Abyssinian/Ethiopian State Formation Process/Territorial Control? 21 3.1 Menelik (1889 – 1913) Emperor 21 3.1.1 Introduction 21 3.1.2 The Colonization of Oromo People 21 3.2 Empire State Under Haile Selassie, 1916 – 1974 37