Red Terror NEVER AGAIN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lenin and the Russian Civil War

Lenin and the Russian Civil War In the months and years after the fall of Tsar Nicholas II’s government, Russia went through incredible, often violent changes. The society was transformed from a peasant society run by an absolute monarchy into a worker’s state run by an all- powerful group that came to be known as the Communist Party. A key to this transformation is Vladimir Lenin. Who Was Lenin? • Born into a wealthy middle-class family background. • Witnessed (when he was 17) the hanging of his brother Aleksandr for revolutionary activity. • Kicked out his university for participating in anti- Tsarist protests. • Took and passed his law exams and served in various law firms in St. Petersburg and elsewhere. • Arrested and sent to Siberia for 3 years for transporting and distributing revolutionary literature. • When WWI started, argued that it should become a revolution of the workers throughout Europe. • Released and lived mostly in exile (Switzerland) until 1917. • Adopted the name “Lenin” (he was born Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov) in exile to hide his activities from the Tsar’s secret police. Lenin and the French Revolution Lenin admired the revolutionaries in France 100 years before his time, though he believed they didn’t go far enough – too much wealth was left in middle class hands. His Bolsheviks used the chaotic and incomplete nature of the French Revolution as a guide - they believed that in order for a communist revolution to succeed, it would need firm leadership from a small group of party leaders – a very different vision from Karl Marx. So, in some ways, Lenin was like Robin Hood – taking from the rich and giving to the poor. -

Victims Reparation for Derg Crimes

Victims Reparation for Derg Crimes: Challenges and Prospects Fisseha M. Tekle Submitted to Central European University Legal Studies Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of LL.M in International Human Rights Law CEU eTD Collection Supervisor: Professor Roger O’keefe 2013 Executive Summary This research is about challenges and prospects to ensure victims’ reparation for mass human rights violations in circumstances where States fail their obligations to avail remedies. International human rights embodied in conventions and customary international laws set the minimum standards States shall guarantee to the subjects of their jurisdiction. Moreover they stipulate the remedies States shall avail in case of violation of those minimum standards. However, it still remains within the power of States to live up to their obligations, or not. Particularly, this paper explores challenges and prospects for claiming reparation for victims of mass atrocities that occurred in Ethiopia between 1974 and 1991 by the Derg era. The findings indicate that there are challenges such as expiry of period of limitation and non-justiciability of constitutional provisions in domestic Courts. And in the presence of these impediments locally, international mechanisms are also blocked due to the principle of State immunity even if those violations pertain to peremptory rules of international law such as prohibition of genocide, torture and grave breaches of the laws of war. This thesis finds innovative reparation mechanisms in jurisprudences of regional and international tribunals with regard to mass human rights violations. However, victims of the Derg crimes face challenges accessing them due to the intricacies of the international law that are ill-fitting to the regime of human rights laws. -

AXUM – Welcoming and Engaging Visitors – Design Report

Pedro Guedes (2010) AXUM – Welcoming and engaging visitors – Design report CONTENTS: Design report 1 Appendix – A 25 Further thoughts on Interpretation Centres Appendix – B 27 Axum signage and paving Presented to Tigray Government and tourism commission officials and stakeholders in Axum in November 2009. NATURE OF SUBMISSION: Design Research This Design report records a creative design approach together with the development of original ideas resulting in an integrated proposal for presenting Axum’s rich tangible and intangible heritage to visitors to this important World Heritage Town. This innovative proposal seeks to use local resources and skills to create a distinct and memorable experience for visitors to Axum. It relies on engaging members of the local community to manage and ‘own’ the various ‘attractions’ for visitors, hopefully keeping a substantial proportion of earnings from tourism in the local community. The proposal combines attitudes to Design with fresh approaches to curatorship that can be applied to other sites. In this study, propositions are tested in several schemes relating to the design of ‘Interpretation centres’ and ideas for exhibits that would bring them to life and engage visitors. ABSTRACT: Axum, in the highlands of Ethiopia was the centre of an important trading empire, controlling the Red Sea and channeling exotic African merchandise into markets of the East and West. In the fourth century (AD), it became one of the first states to adopt Christianity as a state religion. Axum became the major religious centre for the Ethiopian Coptic Church. Axum’s most spectacular archaeological remains are the large carved monoliths – stelae that are concentrated in the Stelae Park opposite the Cathedral precinct. -

The Ethiopian State: Perennial Challenges in the Struggle for Development

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College International Studies Honors Projects International Studies Department 4-26-2016 The thiopiE an State: Perennial Challenges in the Struggle for Development Hawi Tilahune Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tilahune, Hawi, "The thiopE ian State: Perennial Challenges in the Struggle for Development" (2016). International Studies Honors Projects. Paper 21. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors/21 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the International Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Studies Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ethiopian State: Perennial Challenges in the Struggle for Development Hawi Tilahune Presented to the Department of International Studies, Macalester College. Faculty Advisors: Dr. Ahmed I. Samatar and Professor David Blaney 4/26/2016 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 3 ABSTRACT 4 CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 6 I. THE CHALLENGE 6 II. RESEARCH QUESTIONS 7 III. MOTIVATION 8 IV. SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY 10 V. PREPARATION 10 VI. ORGANIZATION 12 CHAPTER II: LITERATURE REVIEW 15 I. THE STATE 15 II. NATIONHOOD AND NATIONALISM 30 III. WORLD ORDER 37 IV. DEVELOPMENT 43 CHAPTER III: BASIC INFORMATION 50 I. PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY 50 II. POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY 51 III. SOCIAL GEOGRAPHY 51 IV. ECONOMY 52 CHAPTER IV: EMPEROR MENELIK II (1889-1913) 54 I. INTRODUCTION 54 II. EUROPEAN IMPERIALISM IN THE HORN 55 III. TERRITORIAL AND CULTURAL EXPANSION 58 IV. -

Local Agency and Individual Initiative in the Evolution of the Holocaust: the Case of Heinrich Himmler

Local Agency and Individual Initiative in the Evolution of the Holocaust: The Case of Heinrich Himmler By: Tanya Pazdernik 25 March 2013 Speaking in the early 1940s on the “grave matter” of the Jews, Heinrich Himmler asserted: “We had the moral right, we had the duty to our people to destroy this people which wanted to destroy us.”1 Appointed Reichsführer of the SS in January 1929, Himmler believed the total annihilation of the Jewish race necessary for the survival of the German nation. As such, he considered the Holocaust a moral duty. Indeed, the Nazi genocide of all “life unworthy of living,” known as the Holocaust, evolved from an ideology held by the highest officials of the Third Reich – an ideology rooted in a pseudoscientific racism that rationalized the systematic murder of over twelve million people, mostly during just a few years of World War Two. But ideologies do not murder. People do. And the leader of the Third Reich, Adolf Hitler, never personally murdered a single Jew. Instead, he relied on his subordinates to implement his often ill-defined visions. Thus, to understand the Holocaust as a broad social phenomenon we must refocus our lens away from an obsession with Hitler and onto his henchmen. One such underling was indeed Himmler. The problem in the lack of consensus among scholars is over the matter of who, precisely, bears responsibility for the Holocaust. Historians even sharply disagree about the place of Adolf Hitler in the decision-making processes of the Third Reich, particularly in regards to the Final Solution. -

The Red Terror in Russia

THE RED TERROR IN RUSSIA BY SERGEY PETROVICH MELGOUNOV A few of a party of nineteen ecclesiastics shot at Yuriev on January 1, 1918—amongst them Bishop Platon (1)—before their removal to the anatomical theatre at Yuriev University. [See p. 118.] TO THE READER ALTHOUGH, for good and sufficient reasons, the translator who has carefully and conscientiously rendered the bulk of this work into English desires to remain anonymous, certain passages in the work have been translated by myself, and the sheets of the manuscript as a whole entrusted to my hands for revision. Hence, if any shortcomings in the rendering should be discerned (as doubtless they will be), they may be ascribed to my fault alone. For the rest, I would ask the reader to remember, when passages in the present tense are met with, that most of this work was written during the years 1928 and 1924. C. J. HOGARTH. PREFACE SERGEY PETROVICH MELGOUNOV, author of this work, was born on December 25, 1879. The son of the well-known historian of the name, he is also a direct descendant of the Freemason who became prominent during the reign of Catherine the Great. Mr. Melgounov graduated in the Historical and Philological Faculty of the University of Moscow, and then proceeded to devote his principal study to the Sectarian movements of Russia, and to write many articles on the subject which, collated into book form, appeared under the title of The Social and Religious Movements of Russia during the Nineteenth Century, and constitute a sequel to two earlier volumes on Sectarian movements during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. -

Holocaust Education Standards Grade 4 Standard 1: SS.4.HE.1

1 Proposed Holocaust Education Standards Grade 4 Standard 1: SS.4.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.4.HE.1.1 Compare and contrast Judaism to other major religions observed around the world, and in the United States and Florida. Grade 5 Standard 1: SS.5.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.5.HE.1.1 Define antisemitism as prejudice against or hatred of the Jewish people. Students will recognize the Holocaust as history’s most extreme example of antisemitism. Teachers will provide students with an age-appropriate definition of with the Holocaust. Grades 6-8 Standard 1: SS.68.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.68.HE.1.1 Define the Holocaust as the planned and systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of European Jews by Nazi Germany and its collaborators between 1933 and 1945. Students will recognize the Holocaust as history’s most extreme example of antisemitism. Students will define antisemitism as prejudice against or hatred of Jewish people. Grades 9-12 Standard 1: SS.HE.912.1. Analyze the origins of antisemitism and its use by the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazi) regime. SS.912.HE.1.1 Define the terms Shoah and Holocaust. Students will distinguish how the terms are appropriately applied in different contexts. SS.912.HE.1.2 Explain the origins of antisemitism. Students will recognize that the political, social and economic applications of antisemitism led to the organized pogroms against Jewish people. Students will recognize that The Protocols of the Elders of Zion are a hoax and utilized as propaganda against Jewish people both in Europe and internationally. -

Prehistory Bronze Age Contacts with Egypt

Prehistory It was not until 1963 that evidence of the presence of ancient hominids was discovered in Ethiopia, many years after similar such discoveries had been made in neighbouring Kenya and Tanzania. The discovery was made by Gerrard Dekker, a Dutch hydrologist, who found Acheulian stone tools that were over a million years old at Kella. Since then many important finds have propelled Ethiopia to the forefront of palaentology. The oldest hominid discovered to date in Ethiopia is the 4.2 million year old Ardipithicus ramidus (Ardi) found by Tim D. White in 1994. The most well known hominid discovery is Lucy, found in the Awash Valley of Ethiopia's Afar region in 1974 by Donald Johanson, and is one of the most complete and best preserved, adult Australopithecine fossils ever uncovered. Lucy's taxonomic name, Australopithecus afarensis, means 'southern ape of Afar', and refers to the Ethiopian region where the discovery was made. Lucy is estimated to have lived 3.2 million years ago. There have been many other notable fossil findings in the country. Near Gona stone tools were uncovered in 1992 that were 2.52 million years old, these are the oldest such tools ever discovered anywhere in the world. In 2010 fossilised animal bones, that were 3.4 million years old, were found with stone-tool-inflicted marks on them in the Lower Awash Valley by an international team, led by Shannon McPherron, which is the oldest evidence of stone tool use ever found anywhere in the world. East Africa, and more specifically the general area of Ethiopia, is widely considered the site of the emergence of early Homo sapiens in the Middle Paleolithic. -

Casanova, Julían, the Spanish Republic and Civil

This page intentionally left blank The Spanish Republic and Civil War The Spanish Civil War has gone down in history for the horrific violence that it generated. The climate of euphoria and hope that greeted the over- throw of the Spanish monarchy was utterly transformed just five years later by a cruel and destructive civil war. Here, Julián Casanova, one of Spain’s leading historians, offers a magisterial new account of this crit- ical period in Spanish history. He exposes the ways in which the Republic brought into the open simmering tensions between Catholics and hard- line anticlericalists, bosses and workers, Church and State, order and revolution. In 1936, these conflicts tipped over into the sacas, paseos and mass killings that are still passionately debated today. The book also explores the decisive role of the international instability of the 1930s in the duration and outcome of the conflict. Franco’s victory was in the end a victory for Hitler and Mussolini, and for dictatorship over democracy. julián casanova is Professor of Contemporary History at the University of Zaragoza, Spain. He is one of the leading experts on the Second Republic and the Spanish Civil War and has published widely in Spanish and in English. The Spanish Republic and Civil War Julián Casanova Translated by Martin Douch CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521493888 © Julián Casanova 2010 This publication is in copyright. -

TINKER TAILOR SOLDIER SPY Screenplay by BRIDGET O

TINKER TAILOR SOLDIER SPY Screenplay by BRIDGET O’CONNOR & PETER STRAUGHAN Based on the novel by John le Carré 1. 1 EXT. HUNGARY - BUDAPEST - 1973 - DAY 1 Budapest skyline, looking towards the Parliament building. From here the world looks serene, peaceful. Then, as we begin to PULL BACK, we hear a faint whine, increasing in volume, until it’s the roar of two MiG jet fighters, cutting across the skyline. The PULL BACK reveals a YOUNG BOY watching the jets, exclaiming excitedly in Hungarian. 2 EXT. BUDAPEST STREET - DAY 2 LATERALLY TRACKING down a bustling street, as the jets scream by overhead. Pedestrians look up. All except one man who continues walking. This is JIM PRIDEAUX. ACROSS THE STREET: More pedestrians. We’re not sure who we’re supposed to be looking at - the short stocky man? The girl in the mini skirt? The man in the checked jacket? A car driving beside Prideaux accelerates out of the frame. Across the street the girl in the mini-skirt peels off into a shop. The stocky man turns and waves to us. But it isn’t Prideaux he’s greeting but another passerby, who walks over, shakes hands. Now we’re left with Prideaux and the Magyar in the checked shirt, neither paying any attention to each other. Just as we are wondering if there is any connection, the two reach a corner and the Magyar, pausing to cross the road, collides with another passerby. He looks over and sees Prideaux has caught the moment of slight clumsiness and gives the smallest of rueful smiles. -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

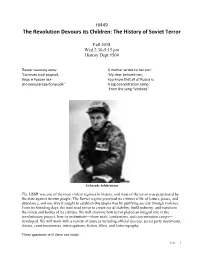

The History of Soviet Terror

HI449 The Revolution Devours its Children: The History of Soviet Terror Fall 2018 Wed 2:30-5:15 pm History Dept #504 Пишет сыночку мать: A mother writes to her son: 'Сыночек мой родной, 'My dear beloved son, Ведь и Россия вся- You know that all of Russia is Это концлагерь большой.' A big concentration camp.' -From the song “Vorkuta” Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn The USSR was one of the most violent regimes in history, and most of the terror was perpetrated by the state against its own people. The Soviet regime promised its citizens a life of leisure, peace, and abundance, and one way it sought to establish this utopia was by purifying society through violence. From its founding days, the state used terror to create social stability, build industry, and transform the minds and bodies of its citizens. We will examine how terror played an integral role in the revolutionary project, how its institutions—show trials, confessions, and concentration camps— developed. We will work with a variety of sources including official decrees, secret party documents, diaries, court testimonies, interrogations, fiction, films, and historiography. Three questions will drive our study: Peri, 1 1. How did the Soviet people experience and understand state violence as a part of everyday life? 2. How was it that mass terror both kept the Soviet state in power as well as eventually unseated it? 3. How can we most judiciously and effectively use personal testimony, which functions both as art and as document, in crafting histories of the terror experience? Instructor: Professor Alexis Peri [email protected] 226 Bay State Rd.