The Dependence of Planetary Tectonics on Mantle Thermal State: Applications to Early Earth Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initiation of Plate Tectonics in the Hadean: Eclogitization Triggered by the ABEL Bombardment

Accepted Manuscript Initiation of plate tectonics in the Hadean: Eclogitization triggered by the ABEL Bombardment S. Maruyama, M. Santosh, S. Azuma PII: S1674-9871(16)30207-9 DOI: 10.1016/j.gsf.2016.11.009 Reference: GSF 514 To appear in: Geoscience Frontiers Received Date: 9 May 2016 Revised Date: 13 November 2016 Accepted Date: 25 November 2016 Please cite this article as: Maruyama, S., Santosh, M., Azuma, S., Initiation of plate tectonics in the Hadean: Eclogitization triggered by the ABEL Bombardment, Geoscience Frontiers (2017), doi: 10.1016/ j.gsf.2016.11.009. This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT MANUSCRIPT ACCEPTED P a g e ‐|‐1111‐‐‐‐ ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT ‐ 1‐ Initiation of plate tectonics in the Hadean: 2‐ Eclogitization triggered by the ABEL 3‐ Bombardment 4‐ 5‐ S. Maruyama a,b,*, M. Santosh c,d,e , S. Azuma a 6‐ a Earth-Life Science Institute, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1, 7‐ Ookayama-Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan 8‐ b Institute for Study of the Earth’s Interior, Okayama University, 827 Yamada, 9‐ Misasa, Tottori 682-0193, Japan 10‐ c Centre for Tectonics, Resources and Exploration, Department of Earth 11‐ Sciences, University of Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia 12‐ d School of Earth Sciences and Resources, China University of Geosciences 13‐ Beijing, 29 Xueyuan Road, Beijing 100083, China 14‐ e Faculty of Science, Kochi University, KochiMANUSCRIPT 780-8520, Japan 15‐ *Corresponding author. -

Stagnant Lid Tectonics: Perspectives from Silicate Planets, Dwarf Planets, Large Moons, and Large Asteroids

Geoscience Frontiers 9 (2018) 103e119 HOSTED BY Contents lists available at ScienceDirect China University of Geosciences (Beijing) Geoscience Frontiers journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gsf Research Paper Stagnant lid tectonics: Perspectives from silicate planets, dwarf planets, large moons, and large asteroids Robert J. Stern a,*, Taras Gerya b, Paul J. Tackley b a Geosciences Department, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX 75083-0688, USA b Department of Earth Sciences, ETH-Zurich, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland article info abstract Article history: To better understand Earth’s present tectonic styleeplate tectonicseand how it may have evolved from Received 7 November 2016 single plate (stagnant lid) tectonics, it is instructive to consider how common it is among similar bodies Received in revised form in the Solar System. Plate tectonics is a style of convection for an active planetoid where lid fragment 22 May 2017 (plate) motions reflect sinking of dense lithosphere in subduction zones, causing upwelling of Accepted 16 June 2017 asthenosphere at divergent plate boundaries and accompanied by focused upwellings, or mantle plumes; Available online 1 July 2017 any other tectonic style is usefully called “stagnant lid” or “fragmented lid”. In 2015 humanity completed a50þ year effort to survey the 30 largest planets, asteroids, satellites, and inner Kuiper Belt objects, Keywords: “ ” Stagnant lid which we informally call planetoids and use especially images of these bodies to infer their tectonic Solar system activity. The four largest planetoids are enveloped in gas and ice (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) Plate tectonics and are not considered. The other 26 planetoids range in mass over 5 orders of magnitude and in Planets diameter over 2 orders of magnitude, from massive Earth down to tiny Proteus; these bodies also range Moons widely in density, from 1000 to 5500 kg/m3. -

Is Plate Tectonics Needed to Evolve Technological Species on Exoplanets?

Geoscience Frontiers 7 (2016) 573e580 HOSTED BY Contents lists available at ScienceDirect China University of Geosciences (Beijing) Geoscience Frontiers journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gsf Research paper Is plate tectonics needed to evolve technological species on exoplanets? Robert J. Stern Geoscience Department, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX 75080, USA article info abstract Article history: As we continue searching for exoplanets, we wonder if life and technological species capable of Received 23 September 2015 communicating with us exists on any of them. As geoscientists, we can also wonder how important is the Received in revised form presence or absence of plate tectonics for the evolution of technological species. This essay considers this 18 November 2015 question, focusing on tectonically active rocky (silicate) planets, like Earth, Venus, and Mars. The Accepted 4 December 2015 development of technological species on Earth provides key insights for understanding evolution on Available online 29 December 2015 exoplanets, including the likely role that plate tectonics may play. An Earth-sized silicate planet is likely Keywords: to experience several tectonic styles over its lifetime, as it cools and its lithosphere thickens, strengthens, Plate tectonics and becomes denser. These include magma ocean, various styles of stagnant lid, and perhaps plate Exoplanets tectonics. Abundant liquid water favors both life and plate tectonics. Ocean is required for early evolution Planetary science of diverse single-celled organisms, then colonies of cells which specialized further to form guts, ap- Intelligent life pendages, and sensory organisms up to the complexity of fish (central nervous system, appendages, eyes). Large expanses of dry land also begin in the ocean, today produced above subduction zones in juvenile arcs and by their coalescence to form continents, although it is not clear that plate tectonics was required to create continental crust on Earth. -

A Continuous Plate-Tectonic Model Using Geophysical Data to Estimate

GEOPHYSICAL JOURNAL INTERNATIONAL, 133, 379–389, 1998 1 A continuous plate-tectonic model using geophysical data to estimate plate margin widths, with a seismicity based example Caroline Dumoulin1, David Bercovici2, Pal˚ Wessel Department of Geology & Geophysics, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, 96822, USA Summary A continuous kinematic model of present day plate motions is developed which 1) provides more realistic models of plate shapes than employed in the original work of Bercovici & Wessel [1994]; and 2) provides a means whereby geophysical data on intraplate deformation is used to estimate plate margin widths for all plates. A given plate’s shape function (which is unity within the plate, zero outside the plate) can be represented by analytic functions so long as the distance from a point inside the plate to the plate’s boundary can be expressed as a single valued function of azimuth (i.e., a single-valued polar function). To allow sufficient realism to the plate boundaries, without the excessive smoothing used by Bercovici and Wessel, the plates are divided along pseudoboundaries; the boundaries of plate sections are then simple enough to be modelled as single-valued polar functions. Moreover, the pseudoboundaries have little or no effect on the final results. The plate shape function for each plate also includes a plate margin function which can be constrained by geophysical data on intraplate deformation. We demonstrate how this margin function can be determined by using, as an example data set, the global seismicity distribution for shallow (depths less than 29km) earthquakes of magnitude greater than 4. -

The Types of Natural Resources on Terrestrial Planets And

OPEN ACCESS Freely available online Jounal of Astrobiology &Outreach Review Article The Types of Natural Resources on Terrestrial Planets and Extraterrestrial Civilizations * Hadi Veysi Department of Agroecology, University of Shahid Beheshti, Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT In addition to energy resources, natural resources such as metals, metalloids, non-metals, hydrocarbons, etc. are among the elements needed for the creation of a civilization. One of the important debates about intelligent life is to know how extraterrestrial civilizations provide the energy and natural resources needed for their development. Previous studies have not discussed much about the ways which intelligent civilizations can access their energy and natural resources. This study discussed the types of natural resources on terrestrial planets and the types of extraterrestrial civilizations that could use them. The results showed that the type of natural resources in terrestrial planets depends on the amount of liquid water, crust lithology, tectonics style, and the presence of microorganisms on the surface of these planets. Among all types of terrestrial planets, plate tectonics style silicate planets have the most complete natural resources. So these planets can be good targets for the natural resources supply of hominid and superhuman extraterrestrial civilizations. Other terrestrial planets such as carbon planets, coreless planets, iron planets, moons and icy dwarf planets, and even gaseous giant planets, although not be civilizable, but have large natural resources that can be used by superhuman civilizations. Keywords: Kardashev scale; Terrestrial planets; Natural resources ABBREVIATION elements, hydrocarbons, etc. to the manufacturing of tools and machines. These resources are found abundantly in terrestrial Li: Lithium, Be: Beryllium, Na: Sodium, Mg: Magnesium, planets, and natural resources very easier extracted from terrestrial Al: Aluminium, K: Potassium, Ca: Calcium, Sc: Scandium, planets than the other cosmic bodies, such as the stars. -

Sterngeryatctnphys18.Pdf

Tectonophysics 746 (2018) 173–198 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Tectonophysics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto Subduction initiation in nature and models: A review T ⁎ Robert J. Sterna, , Taras Geryab a Geosciences Dept., U Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX 75080, USA b Institute of Geophysics, Dept. of Earth Sciences, ETH, Sonneggstrasse 5, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: How new subduction zones form is an emerging field of scientific research with important implications for our Plate tectonics understanding of lithospheric strength, the driving force of plate tectonics, and Earth's tectonic history. We are Subduction making good progress towards understanding how new subduction zones form by combining field studies to Lithosphere identify candidates and reconstruct their timing and magmatic evolution and undertaking numerical modeling (informed by rheological constraints) to test hypotheses. Here, we review the state of the art by combining and comparing results coming from natural observations and numerical models of SI. Two modes of subduction initiation (SI) can be identified in both nature and models, spontaneous and induced. Induced SI occurs when pre-existing plate convergence causes a new subduction zone to form whereas spontaneous SI occurs without pre-existing plate motion when large lateral density contrasts occur across profound lithospheric weaknesses of various origin. We have good natural examples of 3 modes of subduction initiation, one type by induced nu- cleation of a subduction zone (polarity reversal) and two types of spontaneous nucleation of a subduction zone (transform collapse and plumehead margin collapse). In contrast, two proposed types of subduction initiation are not well supported by natural observations: (induced) transference and (spontaneous) passive margin collapse. -

Environmental Geology Chapter 2 -‐ Plate Tectonics and Earth's Internal

Environmental Geology Chapter 2 - Plate Tectonics and Earth’s Internal Structure • Earth’s internal structure - Earth’s layers are defined in two ways. 1. Layers defined By composition and density o Crust-Less dense rocks, similar to granite o Mantle-More dense rocks, similar to peridotite o Core-Very dense-mostly iron & nickel 2. Layers defined By physical properties (solid or liquid / weak or strong) o Lithosphere – (solid crust & upper rigid mantle) o Asthenosphere – “gooey”&hot - upper mantle o Mesosphere-solid & hotter-flows slowly over millions of years o Outer Core – a hot liquid-circulating o Inner Core – a solid-hottest of all-under great pressure • There are 2 types of crust ü Continental – typically thicker and less dense (aBout 2.8 g/cm3) ü Oceanic – typically thinner and denser (aBout 2.9 g/cm3) The Moho is a discontinuity that separates lighter crustal rocks from denser mantle below • How do we know the Earth is layered? That knowledge comes primarily through the study of seismology: Study of earthquakes and seismic waves. We look at the paths and speeds of seismic waves. Earth’s interior boundaries are defined by sudden changes in the speed of seismic waves. And, certain types of waves will not go through liquids (e.g. outer core). • The face of Earth - What we see (Observations) Earth’s surface consists of continents and oceans, including mountain belts and “stable” interiors of continents. Beneath the ocean, there are continental shelfs & slopes, deep sea basins, seamounts, deep trenches and high mountain ridges. We also know that Earth is dynamic and earthquakes and volcanoes are concentrated in certain zones. -

Plate Tectonics and the Cycling of Earth Materials

Plate Tectonics and the cycling of Earth materials Plate tectonics drives the rock cycle: the movement of rocks (and the minerals that comprise them, and the chemical elements that comprise them) from one reservoir to another Arrows are pathways, or fluxes, the I,M.S rocks are processes that “reservoirs” - places move material from one reservoir where material is temporarily stored to another We need to be able to identify these three types of rocks. Why? They convey information about the geologic history of a region. What types of environments are characterized by the processes that produce igneous rocks? What types of environments are preserved by the accumulation of sediment? What types of environments are characterized by the tremendous heat and pressure that produces metamorphic rocks? How the rock cycle integrates into plate tectonics. In order to understand the concept that plate tectonics drives the rock cycle, we need to understand what the theory of plate tectonics says about how the earth works The major plates in today’s Earth (there have been different plates in the Earth’s past!) What is a “plate”? The “plate” of plate tectonics is short for “lithospheric plate” - - the outermost shell of the Earth that behaves as a rigid substance. What does it mean to behave as a rigid substance? The lithosphere is ~150 km thick. It consists of the crust + the uppermost mantle. Below the lithosphere the asthenosphere behaves as a ductile layer: one that flows when stressed It means that when the substance undergoes stress, it breaks (a non-rigid, or ductile, substance flows when stressed; for example, ice flows; what we call a glacier) Since the plates are rigid, brittle 150km thick slabs of the earth, there is a lot of “action”at the edges where they abut other plates We recognize 3 types of plate boundaries, or edges. -

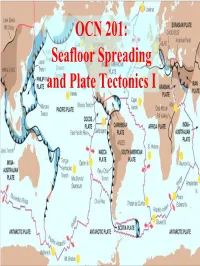

Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics

OCN 201: Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics I Revival of Continental Drift Theory • Kiyoo Wadati (1935) speculated that earthquakes and volcanoes may be associated with continental drift. • Hugo Benioff (1940) plotted locations of deep earthquakes at edge of Pacific “Ring of Fire”. • Earthquakes are not randomly distributed but instead coincide with mid-ocean ridge system. • Evidence of polar wandering. Revival of Continental Drift Theory Wegener’s theory was revived in the 1950’s based on paleomagnetic evidence for “Polar Wandering”. Earth’s Magnetic Field Earth’s magnetic field simulates a bar magnet, but it is caused by A bar magnet with Fe filings convection of liquid Fe in Earth’s aligning along the “lines” of the outer core: the Geodynamo. magnetic field A moving electrical conductor induces a magnetic field. Earth’s magnetic field is toroidal, or “donut-shaped”. A freely moving magnet lies horizontal at the equator, vertical at the poles, and points toward the “North” pole. Paleomagnetism in Rocks • Magnetic minerals (e.g. Magnetite, Fe3 O4 ) in rocks align with Earth’s magnetic field when rocks solidify. • Magnetic alignment is “frozen in” and retained if rock is not subsequently heated. • Can use paleomagnetism of ancient rocks to determine: --direction and polarity of magnetic field --paleolatitude of rock --apparent position of N and S magnetic poles. Apparent Polar Wander Paths • Geomagnetic poles 200 had apparently 200 100 “wandered” 100 systematically with time. • Rocks from different continents gave different paths! Divergence increased with age of rocks. 200 100 Apparent Polar Wander Paths 200 200 100 100 Magnetic poles have never been more the 20o from geographic poles of rotation; rest of apparent wander results from motion of continents! For a magnetic compass, the red end of the needle points to: A. -

Plate Tectonics

Plate tectonics tive motion determines the type of boundary; convergent, divergent, or transform. Earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation occur along these plate boundaries. The lateral relative move- ment of the plates typically varies from zero to 100 mm annually.[2] Tectonic plates are composed of oceanic lithosphere and thicker continental lithosphere, each topped by its own kind of crust. Along convergent boundaries, subduction carries plates into the mantle; the material lost is roughly balanced by the formation of new (oceanic) crust along divergent margins by seafloor spreading. In this way, the total surface of the globe remains the same. This predic- The tectonic plates of the world were mapped in the second half of the 20th century. tion of plate tectonics is also referred to as the conveyor belt principle. Earlier theories (that still have some sup- porters) propose gradual shrinking (contraction) or grad- ual expansion of the globe.[3] Tectonic plates are able to move because the Earth’s lithosphere has greater strength than the underlying asthenosphere. Lateral density variations in the mantle result in convection. Plate movement is thought to be driven by a combination of the motion of the seafloor away from the spreading ridge (due to variations in topog- raphy and density of the crust, which result in differences in gravitational forces) and drag, with downward suction, at the subduction zones. Another explanation lies in the different forces generated by the rotation of the globe and the tidal forces of the Sun and Moon. The relative im- portance of each of these factors and their relationship to each other is unclear, and still the subject of much debate. -

On the Evolution of Terrestrial Planets: Bi-Stability, Stochastic Effects, and the Non-Uniqueness of Tectonic States

Geoscience Frontiers 9 (2018) 91e102 HOSTED BY Contents lists available at ScienceDirect China University of Geosciences (Beijing) Geoscience Frontiers journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gsf Research Paper On the evolution of terrestrial planets: Bi-stability, stochastic effects, and the non-uniqueness of tectonic states Matthew B. Weller a,b,*, Adrian Lenardic c a Institute for Geophysics, University of Texas at Austin, USA b Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, TX, USA c Department of Earth Science, Rice University, Houston, TX 77005, USA article info abstract Article history: The Earth is the only body in the solar system for which significant observational constraints are Received 14 October 2016 accessible to such a degree that they can be used to discriminate between competing models of Earth’s Received in revised form tectonic evolution. It is a natural tendency to use observations of the Earth to inform more general 25 February 2017 models of planetary evolution. However, our understating of Earth’s evolution is far from complete. In Accepted 9 March 2017 recent years, there has been growing geodynamic and geochemical evidence that suggests that plate Available online 22 March 2017 tectonics may not have operated on the early Earth, with both the timing of its onset and the length of its activity far from certain. Recently, the potential of tectonic bi-stability (multiple stable, energetically Keywords: Planetary interiors allowed solutions) has been shown to be dynamically viable, both from analytical analysis and through Mantle convection numeric experiments in two and three dimensions. This indicates that multiple tectonic modes may Lid-state operate on a single planetary body at different times within its temporal evolution. -

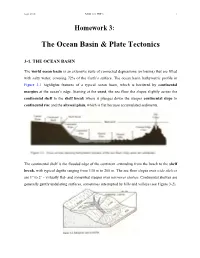

The Ocean Basin & Plate Tectonics

Sept. 2010 MAR 110 HW 3: 1 Homework 3: The Ocean Basin & Plate Tectonics 3-1. THE OCEAN BASIN The world ocean basin is an extensive suite of connected depressions (or basins) that are filled with salty water; covering 72% of the Earth’s surface. The ocean basin bathymetric profile in Figure 3-1 highlights features of a typical ocean basin, which is bordered by continental margins at the ocean’s edge. Starting at the coast, the sea floor the slopes slightly across the continental shelf to the shelf break where it plunges down the steeper continental slope to continental rise and the abyssal plain, which is flat because accumulated sediments. The continental shelf is the flooded edge of the continent -extending from the beach to the shelf break, with typical depths ranging from 130 m to 200 m. The sea floor slopes over wide shelves are 1° to 2° - virtually flat- and somewhat steeper over narrower shelves. Continental shelves are generally gently undulating surfaces, sometimes interrupted by hills and valleys (see Figure 3-2). Sept. 2010 MAR 110 HW 3: 2 The continental slope connects the continental shelf to the deep ocean, with typical depths of 2 to 3 km. While appearing steep in these vertically exaggerated pictures, the bottom slopes of a typical continental slope region are modest angles of 4° to 6°. Continental slope regions adjacent to deep ocean trenches tend to descend somewhat more steeply than normal. Sediments derived from the weathering of the continental material are delivered by rivers and continental shelf flow to the upper continental slope region just beyond the continental shelf break.