Ocean Drilling Program Initial Reports Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Continuous Plate-Tectonic Model Using Geophysical Data to Estimate

GEOPHYSICAL JOURNAL INTERNATIONAL, 133, 379–389, 1998 1 A continuous plate-tectonic model using geophysical data to estimate plate margin widths, with a seismicity based example Caroline Dumoulin1, David Bercovici2, Pal˚ Wessel Department of Geology & Geophysics, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, 96822, USA Summary A continuous kinematic model of present day plate motions is developed which 1) provides more realistic models of plate shapes than employed in the original work of Bercovici & Wessel [1994]; and 2) provides a means whereby geophysical data on intraplate deformation is used to estimate plate margin widths for all plates. A given plate’s shape function (which is unity within the plate, zero outside the plate) can be represented by analytic functions so long as the distance from a point inside the plate to the plate’s boundary can be expressed as a single valued function of azimuth (i.e., a single-valued polar function). To allow sufficient realism to the plate boundaries, without the excessive smoothing used by Bercovici and Wessel, the plates are divided along pseudoboundaries; the boundaries of plate sections are then simple enough to be modelled as single-valued polar functions. Moreover, the pseudoboundaries have little or no effect on the final results. The plate shape function for each plate also includes a plate margin function which can be constrained by geophysical data on intraplate deformation. We demonstrate how this margin function can be determined by using, as an example data set, the global seismicity distribution for shallow (depths less than 29km) earthquakes of magnitude greater than 4. -

Sterngeryatctnphys18.Pdf

Tectonophysics 746 (2018) 173–198 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Tectonophysics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto Subduction initiation in nature and models: A review T ⁎ Robert J. Sterna, , Taras Geryab a Geosciences Dept., U Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX 75080, USA b Institute of Geophysics, Dept. of Earth Sciences, ETH, Sonneggstrasse 5, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: How new subduction zones form is an emerging field of scientific research with important implications for our Plate tectonics understanding of lithospheric strength, the driving force of plate tectonics, and Earth's tectonic history. We are Subduction making good progress towards understanding how new subduction zones form by combining field studies to Lithosphere identify candidates and reconstruct their timing and magmatic evolution and undertaking numerical modeling (informed by rheological constraints) to test hypotheses. Here, we review the state of the art by combining and comparing results coming from natural observations and numerical models of SI. Two modes of subduction initiation (SI) can be identified in both nature and models, spontaneous and induced. Induced SI occurs when pre-existing plate convergence causes a new subduction zone to form whereas spontaneous SI occurs without pre-existing plate motion when large lateral density contrasts occur across profound lithospheric weaknesses of various origin. We have good natural examples of 3 modes of subduction initiation, one type by induced nu- cleation of a subduction zone (polarity reversal) and two types of spontaneous nucleation of a subduction zone (transform collapse and plumehead margin collapse). In contrast, two proposed types of subduction initiation are not well supported by natural observations: (induced) transference and (spontaneous) passive margin collapse. -

Environmental Geology Chapter 2 -‐ Plate Tectonics and Earth's Internal

Environmental Geology Chapter 2 - Plate Tectonics and Earth’s Internal Structure • Earth’s internal structure - Earth’s layers are defined in two ways. 1. Layers defined By composition and density o Crust-Less dense rocks, similar to granite o Mantle-More dense rocks, similar to peridotite o Core-Very dense-mostly iron & nickel 2. Layers defined By physical properties (solid or liquid / weak or strong) o Lithosphere – (solid crust & upper rigid mantle) o Asthenosphere – “gooey”&hot - upper mantle o Mesosphere-solid & hotter-flows slowly over millions of years o Outer Core – a hot liquid-circulating o Inner Core – a solid-hottest of all-under great pressure • There are 2 types of crust ü Continental – typically thicker and less dense (aBout 2.8 g/cm3) ü Oceanic – typically thinner and denser (aBout 2.9 g/cm3) The Moho is a discontinuity that separates lighter crustal rocks from denser mantle below • How do we know the Earth is layered? That knowledge comes primarily through the study of seismology: Study of earthquakes and seismic waves. We look at the paths and speeds of seismic waves. Earth’s interior boundaries are defined by sudden changes in the speed of seismic waves. And, certain types of waves will not go through liquids (e.g. outer core). • The face of Earth - What we see (Observations) Earth’s surface consists of continents and oceans, including mountain belts and “stable” interiors of continents. Beneath the ocean, there are continental shelfs & slopes, deep sea basins, seamounts, deep trenches and high mountain ridges. We also know that Earth is dynamic and earthquakes and volcanoes are concentrated in certain zones. -

Spacing of Faults at the Scale of the Lithosphere and Localization Instability: 2. Application to the Central Indian Basin Laurent G

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 108, NO. B2, 2111, doi:10.1029/2002JB001924, 2003 Spacing of faults at the scale of the lithosphere and localization instability: 2. Application to the Central Indian Basin Laurent G. J. Monte´si1 and Maria T. Zuber2 Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA Received 12 April 2002; revised 21 October 2002; accepted 10 December 2002; published 20 February 2003. [1] Tectonic deformation in the Central Indian Basin (CIB) is organized at two spatial scales: long-wavelength (200 km) undulations of the basement and regularly spaced faults. The fault spacing of order 7–11 km is too short to be explained by lithospheric buckling. We show that the localization instability derived by Monte´si and Zuber [2003] provides an explanation for the fault spacing in the CIB. Localization describes how deformation focuses on narrow zones analogous to faults. The localization instability predicts that localized shear zones form a regular pattern with a characteristic spacing as they develop. The theoretical fault spacing is proportional to the depth to which localization occurs. It also depends on the strength profile and on the effective stress exponent, ne, which is a measure of localization efficiency in the brittle crust and upper mantle. The fault spacing in the CIB can be matched by ne À300 if the faults reach the depth of the brittle– ductile transition (BDT) around 40 km or ne À100 if the faults do not penetrate below 10 km. These values of ne are compatible with laboratory data on frictional velocity weakening. -

Plate Tectonics and the Cycling of Earth Materials

Plate Tectonics and the cycling of Earth materials Plate tectonics drives the rock cycle: the movement of rocks (and the minerals that comprise them, and the chemical elements that comprise them) from one reservoir to another Arrows are pathways, or fluxes, the I,M.S rocks are processes that “reservoirs” - places move material from one reservoir where material is temporarily stored to another We need to be able to identify these three types of rocks. Why? They convey information about the geologic history of a region. What types of environments are characterized by the processes that produce igneous rocks? What types of environments are preserved by the accumulation of sediment? What types of environments are characterized by the tremendous heat and pressure that produces metamorphic rocks? How the rock cycle integrates into plate tectonics. In order to understand the concept that plate tectonics drives the rock cycle, we need to understand what the theory of plate tectonics says about how the earth works The major plates in today’s Earth (there have been different plates in the Earth’s past!) What is a “plate”? The “plate” of plate tectonics is short for “lithospheric plate” - - the outermost shell of the Earth that behaves as a rigid substance. What does it mean to behave as a rigid substance? The lithosphere is ~150 km thick. It consists of the crust + the uppermost mantle. Below the lithosphere the asthenosphere behaves as a ductile layer: one that flows when stressed It means that when the substance undergoes stress, it breaks (a non-rigid, or ductile, substance flows when stressed; for example, ice flows; what we call a glacier) Since the plates are rigid, brittle 150km thick slabs of the earth, there is a lot of “action”at the edges where they abut other plates We recognize 3 types of plate boundaries, or edges. -

On the Dynamics of the Juan De Fuca Plate

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 189 (2001) 115^131 www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl On the dynamics of the Juan de Fuca plate Rob Govers *, Paul Th. Meijer Faculty of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, P.O. Box 80.021, 3508 TA Utrecht, The Netherlands Received 11 October 2000; received in revised form 17 April 2001; accepted 27 April 2001 Abstract The Juan de Fuca plate is currently fragmenting along the Nootka fault zone in the north, while the Gorda region in the south shows no evidence of fragmentation. This difference is surprising, as both the northern and southern regions are young relative to the central Juan de Fuca plate. We develop stress models for the Juan de Fuca plate to understand this pattern of breakup. Another objective of our study follows from our hypothesis that small plates are partially driven by larger neighbor plates. The transform push force has been proposed to be such a dynamic interaction between the small Juan de Fuca plate and the Pacific plate. We aim to establish the relative importance of transform push for Juan de Fuca dynamics. Balancing torques from plate tectonic forces like slab pull, ridge push and various resistive forces, we first derive two groups of force models: models which require transform push across the Mendocino Transform fault and models which do not. Intraplate stress orientations computed on the basis of the force models are all close to identical. Orientations of predicted stresses are in agreement with observations. Stress magnitudes are sensitive to the force model we use, but as we have no stress magnitude observations we have no means of discriminating between force models. -

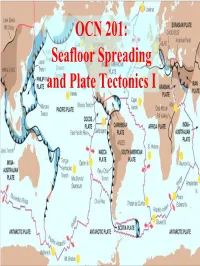

Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics

OCN 201: Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics I Revival of Continental Drift Theory • Kiyoo Wadati (1935) speculated that earthquakes and volcanoes may be associated with continental drift. • Hugo Benioff (1940) plotted locations of deep earthquakes at edge of Pacific “Ring of Fire”. • Earthquakes are not randomly distributed but instead coincide with mid-ocean ridge system. • Evidence of polar wandering. Revival of Continental Drift Theory Wegener’s theory was revived in the 1950’s based on paleomagnetic evidence for “Polar Wandering”. Earth’s Magnetic Field Earth’s magnetic field simulates a bar magnet, but it is caused by A bar magnet with Fe filings convection of liquid Fe in Earth’s aligning along the “lines” of the outer core: the Geodynamo. magnetic field A moving electrical conductor induces a magnetic field. Earth’s magnetic field is toroidal, or “donut-shaped”. A freely moving magnet lies horizontal at the equator, vertical at the poles, and points toward the “North” pole. Paleomagnetism in Rocks • Magnetic minerals (e.g. Magnetite, Fe3 O4 ) in rocks align with Earth’s magnetic field when rocks solidify. • Magnetic alignment is “frozen in” and retained if rock is not subsequently heated. • Can use paleomagnetism of ancient rocks to determine: --direction and polarity of magnetic field --paleolatitude of rock --apparent position of N and S magnetic poles. Apparent Polar Wander Paths • Geomagnetic poles 200 had apparently 200 100 “wandered” 100 systematically with time. • Rocks from different continents gave different paths! Divergence increased with age of rocks. 200 100 Apparent Polar Wander Paths 200 200 100 100 Magnetic poles have never been more the 20o from geographic poles of rotation; rest of apparent wander results from motion of continents! For a magnetic compass, the red end of the needle points to: A. -

Plate Tectonics

Plate tectonics tive motion determines the type of boundary; convergent, divergent, or transform. Earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation occur along these plate boundaries. The lateral relative move- ment of the plates typically varies from zero to 100 mm annually.[2] Tectonic plates are composed of oceanic lithosphere and thicker continental lithosphere, each topped by its own kind of crust. Along convergent boundaries, subduction carries plates into the mantle; the material lost is roughly balanced by the formation of new (oceanic) crust along divergent margins by seafloor spreading. In this way, the total surface of the globe remains the same. This predic- The tectonic plates of the world were mapped in the second half of the 20th century. tion of plate tectonics is also referred to as the conveyor belt principle. Earlier theories (that still have some sup- porters) propose gradual shrinking (contraction) or grad- ual expansion of the globe.[3] Tectonic plates are able to move because the Earth’s lithosphere has greater strength than the underlying asthenosphere. Lateral density variations in the mantle result in convection. Plate movement is thought to be driven by a combination of the motion of the seafloor away from the spreading ridge (due to variations in topog- raphy and density of the crust, which result in differences in gravitational forces) and drag, with downward suction, at the subduction zones. Another explanation lies in the different forces generated by the rotation of the globe and the tidal forces of the Sun and Moon. The relative im- portance of each of these factors and their relationship to each other is unclear, and still the subject of much debate. -

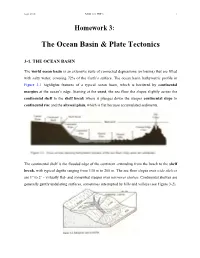

The Ocean Basin & Plate Tectonics

Sept. 2010 MAR 110 HW 3: 1 Homework 3: The Ocean Basin & Plate Tectonics 3-1. THE OCEAN BASIN The world ocean basin is an extensive suite of connected depressions (or basins) that are filled with salty water; covering 72% of the Earth’s surface. The ocean basin bathymetric profile in Figure 3-1 highlights features of a typical ocean basin, which is bordered by continental margins at the ocean’s edge. Starting at the coast, the sea floor the slopes slightly across the continental shelf to the shelf break where it plunges down the steeper continental slope to continental rise and the abyssal plain, which is flat because accumulated sediments. The continental shelf is the flooded edge of the continent -extending from the beach to the shelf break, with typical depths ranging from 130 m to 200 m. The sea floor slopes over wide shelves are 1° to 2° - virtually flat- and somewhat steeper over narrower shelves. Continental shelves are generally gently undulating surfaces, sometimes interrupted by hills and valleys (see Figure 3-2). Sept. 2010 MAR 110 HW 3: 2 The continental slope connects the continental shelf to the deep ocean, with typical depths of 2 to 3 km. While appearing steep in these vertically exaggerated pictures, the bottom slopes of a typical continental slope region are modest angles of 4° to 6°. Continental slope regions adjacent to deep ocean trenches tend to descend somewhat more steeply than normal. Sediments derived from the weathering of the continental material are delivered by rivers and continental shelf flow to the upper continental slope region just beyond the continental shelf break. -

This Dynamic Earth in January of 1992

View of the planet Earth from the Apollo spacecraft. The Red Sea, which separates Saudi Arabia from the continent of Africa, is clearly visible at the top. (Photograph courtesy of NASA.) Contents Preface Historical perspective Developing the theory Understanding plate motions "Hotspots": Mantle Some unanswered questions Plate tectonics and people Endnotes thermal plumes 1 of 77 2002-01-01 11:52 This pdf-version was edited by Peter Lindeberg in December 2001. Any deviation from the original text is non-intentional. This book was originally published in paper form in February 1996 (design and coordination by Martha Kiger; illustrations and production by Jane Russell). It is for sale for $7 from: U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop SSOP Washington, DC 20402-9328 or it can be ordered directly from the U.S. Geological Survey: Call toll-free 1-888-ASK-USGS Or write to USGS Information Services Box 25286, Building 810 Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 303-202-4700; Fax 303-202-4693 ISBN 0-16-048220-8 Version 1.08 The online edition contains all text from the original book in its entirety. Some figures have been modified to enhance legibility at screen resolutions. Many of the images in this book are available in high resolution from the USGS Media for Science page. USGS Home Page URL: http://pubs.usgs.gov/publications/text/dynamic.html Last updated: 01.29.01 Contact: [email protected] 2 of 77 2002-01-01 11:52 In the early 1960s, the emergence of the theory of plate tectonics started a revolution in the earth sciences. -

Plate Tectonics

Plate Tectonics Introduction Continental Drift Seafloor Spreading Plate Tectonics Divergent Plate Boundaries Convergent Plate Boundaries Transform Plate Boundaries Summary This curious world we inhabit is more wonderful than convenient; more beautiful than it is useful; it is more to be admired and enjoyed than used. Henry David Thoreau Introduction • Earth's lithosphere is divided into mobile plates. • Plate tectonics describes the distribution and motion of the plates. • The theory of plate tectonics grew out of earlier hypotheses and observations collected during exploration of the rocks of the ocean floor. You will recall from a previous chapter that there are three major layers (crust, mantle, core) within the earth that are identified on the basis of their different compositions (Fig. 1). The uppermost mantle and crust can be subdivided vertically into two layers with contrasting mechanical (physical) properties. The outer layer, the lithosphere, is composed of the crust and uppermost mantle and forms a rigid outer shell down to a depth of approximately 100 km (63 miles). The underlying asthenosphere is composed of partially melted rocks in the upper mantle that acts in a plastic manner on long time scales. Figure 1. The The asthenosphere extends from about 100 to 300 km (63-189 outermost part of miles) depth. The theory of plate tectonics proposes that the Earth is divided lithosphere is divided into a series of plates that fit together like into two the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. mechanical layers, the lithosphere and Although plate tectonics is a relatively young idea in asthenosphere. comparison with unifying theories from other sciences (e.g., law of gravity, theory of evolution), some of the basic observations that represent the foundation of the theory were made many centuries ago when the first maps of the Atlantic Ocean were drawn. -

Explanatory Notes for the Plate-Tectonic Map of the Circum-Pacific Region

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP SHEETS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCUM-PACIFIC PLATE-TECTONIC MAP SERIES Explanatory Notes for the Plate-Tectonic Map of the Circum-Pacific Region By GEORGE W. MOORE CIRCUM-PACIFIC COUNCIL_a t ENERGY AND MINERAL \il/ RESOURCES THE ARCTIC SHEET OF THIS SERIES IS AVAILABLE FROM U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP DISTRIBUTION BOX 25286, FEDERAL CENTER, DENVER, COLORADO 80225, USA OTHER SHEETS IN THIS SERIES AVAILABLE FROM THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF PETROLEUM GEOLOGISTS BOX 979 TULSA, OKLAHOMA 74101, USA 1992 CIRCUM-PACIFIC COUNCIL FOR ENERGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES Michel T. Halbouty, Chair CIRCUM-PACIFIC MAP PROJECT John A. Reinemund, Director George Gryc, General Chair Explanatory Notes to Supplement the PLATE-TECTONIC MAP OF THE CIRCUM-PACIFIC REGION Jose Corvalan Dv Chair, Southeast Quadrant Panel lan W.D. Dalziel, Chair, Antarctic Panel Kenneth J. Drummond, Chair, Northeast Quadrant Panel R. Wallace Johnson, Chair, Southwest Quadrant Panel George W. Moore, Chair, Arctic Panel Tomoyuki Moritani, Chair, Northwest Quadrant Panel TECTONIC ELEMENTS George W. Moore, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA Nikita A. Bogdanov, Institute of the Lithosphere, Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia Jose Corvalan, Servicio Nacional de Geologia y Mineria, Santiago, Chile Campbell Craddock, Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin H. Frederick Doutch, Bureau of Mineral Resources, Canberra, Australia Kenneth J. Drummond, Mobil Oil Canada, Ltd., Calgary, Alberta, Canada Chikao Nishiwaki, Institute for International Mineral Resources Development, Fujinomiya, Japan Tomotsu Nozawa, Geological Survey of Japan, Tsukuba, Japan Gordon H. Packham, Department of Geophysics, University of Sydney, Australia Solomon M.