A Continuous Plate-Tectonic Model Using Geophysical Data to Estimate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geophysics (3 Credits) Spring 2018

GEO 3010 – Geophysics (3 credits) Spring 2018 Lecture: FASB 250, 10:45-11:35 am, M & W Lab: FASB 250, 2:00-5:00 pm, M or W Instructor: Fan-Chi Lin (Assistant Professor, Dept. of Geology & Geophysics) Office: FASB 271 Phone: 801-581-4373 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: M, W 11:45 am - 1:00 pm. Please feel free to email me if you would like to make an appointment to meet at a different time. Teaching Assistants: Elizabeth Berg ([email protected]) FASB 288 Yadong Wang ([email protected]) FASB 288 Office Hours: T, H 1:00-3:00 pm Website: http://noise.earth.utah.edu/GEO3010/ Course Description: Prerequisite: MATH 1220 (Calculus II). Co-requisite: GEO 3080 (Earth Materials I). Recommended Prerequisite: PHYS 2220 (Phycs For Scien. & Eng. II). Fulfills Quantitative Intensive BS. Applications of physical principles to solid-earth dynamics and solid-earth structure, at both the scale of global tectonics and the smaller scale of subsurface exploration. Acquisition, modeling, and interpretation of seismic, gravity, magnetic, and electrical data in the context of exploration, geological engineering, and environmental problems. Two lectures, one lab weekly. 1. Policies Grades: Final grades are based on following weights: • Homework (25 %) • Labs (25 %) • Exam 1-3 (10% each) • Final (20 %) Homework: There will be approximately 6 homework sets. Homework must be turned in by 5 pm of the day they are due. 10 % will be marked off for each day they are late. Homework will not be accepted 3 days after the due day. Geophysics – GEO 3010 1 Labs: Do not miss labs! In general you will not have a chance to make up missed labs. -

Geophysical Methods Commonly Employed for Geotechnical Site Characterization TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2008 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH Number E-C130 October 2008 Geophysical Methods Commonly Employed for Geotechnical Site Characterization TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2008 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS Chair: Debra L. Miller, Secretary, Kansas Department of Transportation, Topeka Vice Chair: Adib K. Kanafani, Cahill Professor of Civil Engineering, University of California, Berkeley Division Chair for NRC Oversight: C. Michael Walton, Ernest H. Cockrell Centennial Chair in Engineering, University of Texas, Austin Executive Director: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2008–2009 TECHNICAL ACTIVITIES COUNCIL Chair: Robert C. Johns, Director, Center for Transportation Studies, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Technical Activities Director: Mark R. Norman, Transportation Research Board Paul H. Bingham, Principal, Global Insight, Inc., Washington, D.C., Freight Systems Group Chair Shelly R. Brown, Principal, Shelly Brown Associates, Seattle, Washington, Legal Resources Group Chair Cindy J. Burbank, National Planning and Environment Practice Leader, PB, Washington, D.C., Policy and Organization Group Chair James M. Crites, Executive Vice President, Operations, Dallas–Fort Worth International Airport, Texas, Aviation Group Chair Leanna Depue, Director, Highway Safety Division, Missouri Department of Transportation, Jefferson City, System Users Group Chair Arlene L. Dietz, A&C Dietz and Associates, LLC, Salem, Oregon, Marine Group Chair Robert M. Dorer, Acting Director, Office of Surface Transportation Programs, Volpe National Transportation Systems Center, Research and Innovative Technology Administration, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Rail Group Chair Karla H. Karash, Vice President, TranSystems Corporation, Medford, Massachusetts, Public Transportation Group Chair Mary Lou Ralls, Principal, Ralls Newman, LLC, Austin, Texas, Design and Construction Group Chair Katherine F. Turnbull, Associate Director, Texas Transportation Institute, Texas A&M University, College Station, Planning and Environment Group Chair Daniel S. -

The Reunification of Seismology and Geophysics Brad Artman Exploration Geophysics – a Brief History

The Reunification of Seismology and Geophysics Brad Artman Exploration geophysics – a brief history J.C. Karcher patents the reflection seismic method, focused the exploration geophysicist for the next century Beno Guttenberg becomes a professor of seismology Gas research institute, Teledyne Geotech, & Sandia National Labs develop equipment and techniques for microseismic monitoring to illuminate hydraulic fracturing 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2013 Rapid advances in computational capabilities allow processing of ever-larger data volumes with more complete physics Exploration geophysics begins (re) learning earthquake seismology to commercialize microseismic monitoring Today, we have the opportunity to capitalize on the strengths of 100 yrs of development in both communities © Spectraseis Inc. 2013 2 Strength comparison To extract the full Seismology Geophysics potential from these Better sensors More sensors measurements, Better physics More compute horsepower we must capture the best of both Bigger events Smaller domain knowledge bases. Seismologists use cheap computers (grad. students) to do very thorough analysis on small numbers of traces. Geophysicists use cheap computers (clusters) to do good- enough approximations on very large numbers of traces. The merger of these fields is an historic opportunity to do exciting and valuable work © Spectraseis Inc. 2013 3 Agenda Sensor selection Survey design Processing algorithms and computer requirements Conclusions © Spectraseis Inc. 2013 4 Fracture mechanisms Compensated Linear Isotropic Double Couple Vector Dipole (explosion) (DC) (CLVD) P-waves only P- and S-waves P- and S-waves All fractures can be decomposed into these three mechanisms © Spectraseis Inc. 2013 5 DC radiation and particle motion Particle motion of P waves is compressional and in the same direction direction to the traveling wavefront. -

Equivalence of Current–Carrying Coils and Magnets; Magnetic Dipoles; - Law of Attraction and Repulsion, Definition of the Ampere

GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) THE EARTH'S MAGNETIC FIELD OUTLINE Magnetism Magnetic forces: - equivalence of current–carrying coils and magnets; magnetic dipoles; - law of attraction and repulsion, definition of the ampere. Magnetic fields: - magnetic fields from electrical currents and magnets; magnetic induction B and lines of magnetic induction. The geomagnetic field The magnetic elements: (N, E, V) vector components; declination (azimuth) and inclination (dip). The external field: diurnal variations, ionospheric currents, magnetic storms, sunspot activity. The internal field: the dipole and non–dipole fields, secular variations, the geocentric axial dipole hypothesis, geomagnetic reversals, seabed magnetic anomalies, The dynamo model Reasons against an origin in the crust or mantle and reasons suggesting an origin in the fluid outer core. Magnetohydrodynamic dynamo models: motion and eddy currents in the fluid core, mechanical analogues. Background reading: Fowler §3.1 & 7.9.2, Lowrie §5.2 & 5.4 GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) MAGNETIC FORCES Magnetic forces are forces associated with the motion of electric charges, either as electric currents in conductors or, in the case of magnetic materials, as the orbital and spin motions of electrons in atoms. Although the concept of a magnetic pole is sometimes useful, it is diácult to relate precisely to observation; for example, all attempts to find a magnetic monopole have failed, and the model of permanent magnets as magnetic dipoles with north and south poles is not particularly accurate. Consequently moving charges are normally regarded as fundamental in magnetism. Basic observations 1. Permanent magnets A magnet attracts iron and steel, the attraction being most marked close to its ends. -

Sterngeryatctnphys18.Pdf

Tectonophysics 746 (2018) 173–198 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Tectonophysics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto Subduction initiation in nature and models: A review T ⁎ Robert J. Sterna, , Taras Geryab a Geosciences Dept., U Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX 75080, USA b Institute of Geophysics, Dept. of Earth Sciences, ETH, Sonneggstrasse 5, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: How new subduction zones form is an emerging field of scientific research with important implications for our Plate tectonics understanding of lithospheric strength, the driving force of plate tectonics, and Earth's tectonic history. We are Subduction making good progress towards understanding how new subduction zones form by combining field studies to Lithosphere identify candidates and reconstruct their timing and magmatic evolution and undertaking numerical modeling (informed by rheological constraints) to test hypotheses. Here, we review the state of the art by combining and comparing results coming from natural observations and numerical models of SI. Two modes of subduction initiation (SI) can be identified in both nature and models, spontaneous and induced. Induced SI occurs when pre-existing plate convergence causes a new subduction zone to form whereas spontaneous SI occurs without pre-existing plate motion when large lateral density contrasts occur across profound lithospheric weaknesses of various origin. We have good natural examples of 3 modes of subduction initiation, one type by induced nu- cleation of a subduction zone (polarity reversal) and two types of spontaneous nucleation of a subduction zone (transform collapse and plumehead margin collapse). In contrast, two proposed types of subduction initiation are not well supported by natural observations: (induced) transference and (spontaneous) passive margin collapse. -

Environmental Geology Chapter 2 -‐ Plate Tectonics and Earth's Internal

Environmental Geology Chapter 2 - Plate Tectonics and Earth’s Internal Structure • Earth’s internal structure - Earth’s layers are defined in two ways. 1. Layers defined By composition and density o Crust-Less dense rocks, similar to granite o Mantle-More dense rocks, similar to peridotite o Core-Very dense-mostly iron & nickel 2. Layers defined By physical properties (solid or liquid / weak or strong) o Lithosphere – (solid crust & upper rigid mantle) o Asthenosphere – “gooey”&hot - upper mantle o Mesosphere-solid & hotter-flows slowly over millions of years o Outer Core – a hot liquid-circulating o Inner Core – a solid-hottest of all-under great pressure • There are 2 types of crust ü Continental – typically thicker and less dense (aBout 2.8 g/cm3) ü Oceanic – typically thinner and denser (aBout 2.9 g/cm3) The Moho is a discontinuity that separates lighter crustal rocks from denser mantle below • How do we know the Earth is layered? That knowledge comes primarily through the study of seismology: Study of earthquakes and seismic waves. We look at the paths and speeds of seismic waves. Earth’s interior boundaries are defined by sudden changes in the speed of seismic waves. And, certain types of waves will not go through liquids (e.g. outer core). • The face of Earth - What we see (Observations) Earth’s surface consists of continents and oceans, including mountain belts and “stable” interiors of continents. Beneath the ocean, there are continental shelfs & slopes, deep sea basins, seamounts, deep trenches and high mountain ridges. We also know that Earth is dynamic and earthquakes and volcanoes are concentrated in certain zones. -

Plate Tectonics and the Cycling of Earth Materials

Plate Tectonics and the cycling of Earth materials Plate tectonics drives the rock cycle: the movement of rocks (and the minerals that comprise them, and the chemical elements that comprise them) from one reservoir to another Arrows are pathways, or fluxes, the I,M.S rocks are processes that “reservoirs” - places move material from one reservoir where material is temporarily stored to another We need to be able to identify these three types of rocks. Why? They convey information about the geologic history of a region. What types of environments are characterized by the processes that produce igneous rocks? What types of environments are preserved by the accumulation of sediment? What types of environments are characterized by the tremendous heat and pressure that produces metamorphic rocks? How the rock cycle integrates into plate tectonics. In order to understand the concept that plate tectonics drives the rock cycle, we need to understand what the theory of plate tectonics says about how the earth works The major plates in today’s Earth (there have been different plates in the Earth’s past!) What is a “plate”? The “plate” of plate tectonics is short for “lithospheric plate” - - the outermost shell of the Earth that behaves as a rigid substance. What does it mean to behave as a rigid substance? The lithosphere is ~150 km thick. It consists of the crust + the uppermost mantle. Below the lithosphere the asthenosphere behaves as a ductile layer: one that flows when stressed It means that when the substance undergoes stress, it breaks (a non-rigid, or ductile, substance flows when stressed; for example, ice flows; what we call a glacier) Since the plates are rigid, brittle 150km thick slabs of the earth, there is a lot of “action”at the edges where they abut other plates We recognize 3 types of plate boundaries, or edges. -

SEG Near-Surface Geophysics Technical Section Annual Meeting

The 2018 SEG Near-Surface Geophysics Technical Section Proposed Technical Sessions (Please note, the identified session topics here are not inclusive of all possible near-surface geophysics technical sessions, but have been identified at this point.) Session topic/title Session description and objective Coupled above and below-ground Description: There have been significant advances in a variety of geophysical techniques in the past decades to characterize near- monitoring using geophysics, UAV, surface critical zone heterogeneity, including hydrological and biogeochemical properties, as well as near-surface spatiotemporal and remote sensing dynamics such as temperature, soil moisture and geochemical changes. At the same time, above-ground characterization is evolving significantly – particularly in airborne platforms and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) – to capture the spatiotemporal dynamics in microtopography, vegetation and others. The critical link between near-surface and surface properties has been recognized, since surface processes dictates the evolution of near-surface environments evolve (e.g., topography influences surface/subsurface flow, affecting bedrock weathering), while near-surface properties (such as soil texture) control vegetation and topography. Now that geophysics and airborne technologies can capture both surface and near-surface spatiotemporal dynamics at high resolution in a spatially extensive manner, there is a great opportunity to advance the understanding of this coupled surface and near-surface system. This session calls for a variety of contributions on this topic, including coupled above/below-ground sensing technologies, new geophysical techniques to characterize the interactions between near-surface and surface environments. Near-surface modeling using Description: The first few meters of the subsurface is of paramount importance to the engineering and environmental industry. -

Introduction to Environmental Geophysics Student Manual

United States Offi ce of Emergency and July 2014 Environmental Protection Remedial Response www.epa.gov/superfund Agency Washington, DC 20460 Superfund Introduction to Environmental Geophysics Student Manual Overview of Geophysical Methods OVERVIEW OF GEOPHYSICAL METHODS Geophysical Surveys Characterize geology Characterize hydrogeology Locate metal targets and voids Physical Properties Measured Velocity Seismic Radar Electrical Impedance Electromagnetics Resistivity Magnetic Magnetics Density Gravity Overview of Environmental Geophysics 1 Overview of Geophysical Methods Magnetics Measures natural magnetic field Map anomalies in magnetic field Detects iron and steel Geometrics Cesium Magnetometer Electromagnetics (EM) Generates electrical and magnetic fields Measures the conductivity of target Locates metal targets Overview of Environmental Geophysics 2 Overview of Geophysical Methods EM-31 Marion Landfill, Marion, IN EM-61 Geonics EM-61 EM Metal Detector Resistivity Injects current into ground Measures resultant voltage Determines apparent resistivity of layers Maps geologic beds and water table Overview of Environmental Geophysics 3 Overview of Geophysical Methods Sting Resistivity Unit Seismic Methods Uses acoustic energy Refraction - Determines velocity and thickness of geologic beds Reflection - Maps geologic layers and bed topography Seistronix Seismograph Overview of Environmental Geophysics 4 Overview of Geophysical Methods Gravity Measures gravitational field Used to determine density of materials under -

NCHRP Synthesis 357 – Use of Geophysics for Transportation

NATIONAL COOPERATIVE HIGHWAY RESEARCH NCHRP PROGRAM SYNTHESIS 357 Use of Geophysics for Transportation Projects A Synthesis of Highway Practice TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 2006 (Membership as of March 2006) OFFICERS Chair: Michael D. Meyer, Professor, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology Vice Chair: Linda S. Watson, Executive Director, LYNX—Central Florida Regional Transportation Authority Executive Director: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board MEMBERS MICHAEL W. BEHRENS, Executive Director, Texas DOT ALLEN D. BIEHLER, Secretary, Pennsylvania DOT JOHN D. BOWE, Regional President, APL Americas, Oakland, CA LARRY L. BROWN, SR., Executive Director, Mississippi DOT DEBORAH H. BUTLER, Vice President, Customer Service, Norfolk Southern Corporation and Subsidiaries, Atlanta, GA ANNE P. CANBY, President, Surface Transportation Policy Project, Washington, DC DOUGLAS G. DUNCAN, President and CEO, FedEx Freight, Memphis, TN NICHOLAS J. GARBER, Henry L. Kinnier Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Virginia, Charlottesville ANGELA GITTENS, Vice President, Airport Business Services, HNTB Corporation, Miami, FL GENEVIEVE GIULIANO, Professor and Senior Associate Dean of Research and Technology, School of Policy, Planning, and Development, and Director, METRANS National Center for Metropolitan Transportation Research, USC, Los Angeles SUSAN HANSON, Landry University Professor of Geography, Graduate School of Geography, Clark University JAMES R. HERTWIG, President, CSX Intermodal, Jacksonville, FL ADIB K. KANAFANI, Cahill Professor of Civil Engineering, University of California, Berkeley HAROLD E. LINNENKOHL, Commissioner, Georgia DOT SUE MCNEIL, Professor, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Delaware DEBRA L. MILLER, Secretary, Kansas DOT MICHAEL R. MORRIS, Director of Transportation, North Central Texas Council of Governments CAROL A. MURRAY, Commissioner, New Hampshire DOT JOHN R. -

APPLICATION of GEOPHYSICAL TECHNIQUES to MINERALS-RELATED ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS by Ken Watson, David Fitterman, R.W

APPLICATION OF GEOPHYSICAL TECHNIQUES TO MINERALS-RELATED ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS By Ken Watson, David Fitterman, R.W. Saltus, Anne McCafferty, Gregg Swayze, Stan Church, Kathy Smith, Marty Goldhaber, Stan Robson, and Pete McMahon Open-File Report 01-458 2001 This report is preliminary and had not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Geophysics in Mineral-Environmental Applications 2 Contents 1 Executive Summary 3 1.1 Application of methods . 3 1.2 Mineral-environmental problems . 3 1.3 Controlling processes . 4 1.4 Geophysical techniques . 5 1.4.1 Electrical and electromagnetic methods . 5 1.4.2 Seismic methods . 6 1.4.3 Thermal methods . 6 1.4.4 Remote sensing methods . 6 1.4.5 Potential field methods . 7 1.4.6 Other geophysical methods . 7 2 Introduction 8 3 Mineral-environmental Applications of Geophysics 10 4 Mineral-environmental Problems 13 4.1 The sources of potentially harmful substances . 15 4.2 Mobility of potentially harmful substances . 15 4.3 Transport of potentially harmful substances . 16 4.4 Pathways for transport of potentially harmful substances . 17 4.5 Interaction of potentially harmful substances with the environment . 18 5 Processes Controlling Mineral-Environmental Problems 18 5.1 Geochemical processes . 19 5.1.1 Chemical Weathering (near-surface reactions) . 19 5.1.2 Deep alteration (reactions at depth) . 20 5.1.3 Microbial catalysis . -

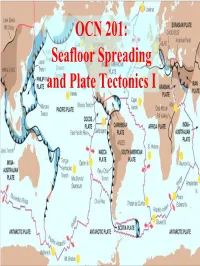

Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics

OCN 201: Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics I Revival of Continental Drift Theory • Kiyoo Wadati (1935) speculated that earthquakes and volcanoes may be associated with continental drift. • Hugo Benioff (1940) plotted locations of deep earthquakes at edge of Pacific “Ring of Fire”. • Earthquakes are not randomly distributed but instead coincide with mid-ocean ridge system. • Evidence of polar wandering. Revival of Continental Drift Theory Wegener’s theory was revived in the 1950’s based on paleomagnetic evidence for “Polar Wandering”. Earth’s Magnetic Field Earth’s magnetic field simulates a bar magnet, but it is caused by A bar magnet with Fe filings convection of liquid Fe in Earth’s aligning along the “lines” of the outer core: the Geodynamo. magnetic field A moving electrical conductor induces a magnetic field. Earth’s magnetic field is toroidal, or “donut-shaped”. A freely moving magnet lies horizontal at the equator, vertical at the poles, and points toward the “North” pole. Paleomagnetism in Rocks • Magnetic minerals (e.g. Magnetite, Fe3 O4 ) in rocks align with Earth’s magnetic field when rocks solidify. • Magnetic alignment is “frozen in” and retained if rock is not subsequently heated. • Can use paleomagnetism of ancient rocks to determine: --direction and polarity of magnetic field --paleolatitude of rock --apparent position of N and S magnetic poles. Apparent Polar Wander Paths • Geomagnetic poles 200 had apparently 200 100 “wandered” 100 systematically with time. • Rocks from different continents gave different paths! Divergence increased with age of rocks. 200 100 Apparent Polar Wander Paths 200 200 100 100 Magnetic poles have never been more the 20o from geographic poles of rotation; rest of apparent wander results from motion of continents! For a magnetic compass, the red end of the needle points to: A.