The Origins of the Artistic Interactions Between the Assyrian Empire and North Syria Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015–2016 Annual Report

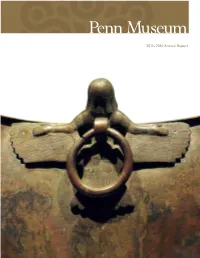

2015–2016 Annual Report 2015–2016 Annual Report 3 EXECUTIVE MESSAGE 4 THE NEW PENN MUSEUM 7 YEAR IN REVIEW 8 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE GEOGRAPHY 8 Teaching & Research: Penn Museum-Sponsored Field Projects 10 Excavations at Anubis-Mountain, South Abydos (Egypt) 12 Gordion Archaeological Project (Turkey) — Historical Landscape Preservation at Gordion — Gordion Cultural Heritage Education Project 16 The Penn Cultural Heritage Center — Conflict Culture Research Network (Global) — Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria & Iraq Project (Syria and Iraq) — Tihosuco Heritage Preservation & Community Development Project (Mexico) — Wayka Heritage Project (California, USA) 20 Pelekita Cave in Eastern Crete (Greece) 21 Late Pleistocene Pyrotechnology (France) 22 The Life & Times of Emma Allison (Canada) 23 On the Wampum Trail (North America) 24 Louis Shotridge & the Penn Museum (Alaska, USA) 25 Smith Creek Archaeological Project (Mississippi, USA) 26 Silver Reef Project (Utah, USA) 26 South Jersey (Vineland) Project (New Jersey, USA) 27 Collections: New Acquisitions 31 Collections: Outgoing Loans & Traveling Exhibitions 35 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE NUMBERS 40 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE MONTH 57 SUPPORTING THE MISSION 58 Leadership Supporters 62 Loren Eiseley Society 64 Expedition Circle 66 The Annual Fund 67 Sara Yorke Stevenson Legacy Circle 68 Corporate, Foundation, & Government Agency Supporters Objects on the cover, inside cover, and above were featured 71 THE GIFT OF TIME in the special exhibition The Golden Age of King Midas, from 72 Exhibition Advisors & Contributors February 13, 2016 through November 27, 2016. 74 Penn Museum Volunteers On the cover: Bronze cauldron with siren and demon 76 Board of Overseers attachments. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations 18516. -

In the Late Bronze

ARCHAEOLOGY INTERNATIONAL Hittites and "barbarians" in the Late Bronze Age: regional survey in northern Turkey Roger Matthews The Hittites have attracted less attention fr om British archae ologists than other Bronze Age states of ancient Southwest Asia, and yet in the second millennium BC they controlled most of Anatolia and at the peak of their power they even conquered eHattusa Babylon. Here the Director of the British Institute of Archaeol ogy at Ankara describes new research on the northwest fr ontier •Gordion of the Hi ttite empire. Ku�akli• -t its peak the Hittite state of linen", probably disparagingly, but were the Late Bronze Age was one prepared to sit down and negotiate with ANATOLIA of the most powerful political them on the many occasions when military Aentities ever to have arisen in action failed to subdue them. However, in southwestern Asia. The Hit archaeological terms we know little about tites held sway over almost the whole of the Kaska people or about the landscapes Anatolia (modern Asiatic Turkey) and, in which they lived, despite their proxim sporadically, over large swathes of adja ity to Hattusa and their undoubted signif cent territory too. The high point of Hittite icance in the evolution of the Hittite state. expansion came with the capture of Baby Ion in 1595 BC by Mursili I, which brought Project Paphlagonia and the Late to a violent end the 300-year-old First Bronze Age landscape of northern N Dynasty ofBabylon, of which Hammurabi Tu rkey was the dominant figure. But a marked In 1997 I began a five-year programme of characteristic of the Hittite state is the multi-period regional survey, on behalf of t rapidity and severity with which the the British Institute of Archaeology at extent of its territory waxed and waned. -

The Dynamics of Syria's Civil

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service INFRASTRUCTURE AND of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY Support RAND SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Browse Reports & Bookstore TERRORISM AND Make a charitable contribution HOMELAND SECURITY For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. RAND perspectives (PEs) present informed perspective on a timely topic that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND perspectives undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Perspective C O R P O R A T I O N Expert insights on a timely policy issue The Dynamics of Syria’s Civil War Brian Michael Jenkins Principal Observations One-third of the population has fled the country or has been displaced internally. -

Next Steps in Syria

Next Steps in Syria BY JUDITH S. YAPHE early three years since the start of the Syrian civil war, no clear winner is in sight. Assassinations and defections of civilian and military loyalists close to President Bashar Nal-Assad, rebel success in parts of Aleppo and other key towns, and the spread of vio- lence to Damascus itself suggest that the regime is losing ground to its opposition. The tenacity of government forces in retaking territory lost to rebel factions, such as the key town of Qusayr, and attacks on Turkish and Lebanese military targets indicate, however, that the regime can win because of superior military equipment, especially airpower and missiles, and help from Iran and Hizballah. No one is prepared to confidently predict when the regime will collapse or if its oppo- nents can win. At this point several assessments seem clear: ■■ The Syrian opposition will continue to reject any compromise that keeps Assad in power and imposes a transitional government that includes loyalists of the current Baathist regime. While a compromise could ensure continuity of government and a degree of institutional sta- bility, it will almost certainly lead to protracted unrest and reprisals, especially if regime appoin- tees and loyalists remain in control of the police and internal security services. ■■ How Assad goes matters. He could be removed by coup, assassination, or an arranged exile. Whether by external or internal means, building a compromise transitional government after Assad will be complicated by three factors: disarray in the Syrian opposition, disagreement among United Nations (UN) Security Council members, and an intransigent sitting govern- ment. -

Herding, Warfare, and a Culture of Honor: Global Evidence

Herding,Warfare, and a Culture of Honor: Global Evidence* Yiming Cao† Benjamin Enke‡ Armin Falk§ Paola Giuliano¶ Nathan Nunn|| 7 September 2021 Abstract: According to the widely known ‘culture of honor’ hypothesis from social psychology, traditional herding practices have generated a value system conducive to revenge-taking and violence. We test the economic significance of this idea at a global scale using a combination of ethnographic and folklore data, global information on conflicts, and multinational surveys. We find that the descendants of herders have significantly more frequent and severe conflict today, and report being more willing to take revenge in global surveys. We conclude that herding practices generated a functional psychology that plays a role in shaping conflict across the globe. Keywords: Culture of honor, conflict, punishment, revenge. *We thank Anke Becker, Dov Cohen, Pauline Grosjean, Joseph Henrich, Stelios Michalopoulos and Thomas Talhelm for useful discussions and/or comments on the paper. †Boston University. (email: [email protected]) ‡Harvard University and NBER. (email: [email protected]) §briq and University of Bonn. (email: [email protected]) ¶University of California Los Angeles and NBER. (email: [email protected]) ||Harvard University and CIFAR. (email: [email protected]) 1. Introduction A culture of honor is a bundle of values, beliefs, and preferences that induce people to protect their reputation by answering threats and unkind behavior with revenge and violence. According to a widely known hypothesis, that was most fully developed by Nisbett( 1993) and Nisbett and Cohen( 1996), a culture of honor is believed to reflect an economically-functional cultural adaptation that arose in populations that depended heavily on animal herding (pastoralism).1 The argument is that, relative to farmers, herders are more vulnerable to exploitation and theft because their livestock is a valuable and mobile asset. -

Syria, April 2005

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Syria, April 2005 COUNTRY PROFILE: SYRIA April 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Syrian Arab Republic (Al Jumhuriyah al Arabiyah as Suriyah). Short Form: Syria. Term for Citizen(s): Syrian(s). Capital: Damascus (population estimated at 5 million in 2004). Other Major Cities: Aleppo (4.5 million), Homs (1.8 million), Hamah (1.6 million), Al Hasakah (1.3 million), Idlib (1.2 million), and Latakia (1 million). Independence: Syrians celebrate their independence on April 17, known as Evacuation Day, in commemoration of the departure of French forces in 1946. Public Holidays: Public holidays observed in Syria include New Year’s Day (January 1); Revolution Day (March 8); Evacuation Day (April 17); Egypt’s Revolution Day (July 23); Union of Syria, Egypt, and Libya (September 1); Martyrs’ Day, to commemorate the public hanging of 21 dissidents in 1916 (May 6); the beginning of the 1973 October War (October 6); National Day (November 16); and Christmas Day (December 25). Religious feasts with movable dates include Eid al Adha, the Feast of the Sacrifice; Muharram, the Islamic New Year; Greek Orthodox Easter; Mouloud/Yum an Nabi, celebration of the birth of Muhammad; Leilat al Meiraj, Ascension of Muhammad; and Eid al Fitr, the end of Ramadan. In 2005 movable holidays will be celebrated as follows: Eid al Adha, January 21; Muharram, February 10; Greek Orthodox Easter, April 29–May 2; Mouloud, April 21; Leilat al Meiraj, September 2; and Eid al Fitr, November 4. Flag: The Syrian flag consists of three equal horizontal stripes of red, white, and black with two small green, five-pointed stars in the middle of the white stripe. -

The Rise of Arabism in Syria Author(S): C

The Rise of Arabism in Syria Author(s): C. Ernest Dawn Source: Middle East Journal, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Spring, 1962), pp. 145-168 Published by: Middle East Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4323468 Accessed: 27/08/2009 15:10 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mei. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Middle East Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Middle East Journal. http://www.jstor.org THE RISE OF ARABISMIN SYRIA C. Ernest Dawn JN the earlyyears of the twentiethcentury, two ideologiescompeted for the loyalties of the Arab inhabitantsof the Ottomanterritories which lay to the east of Suez. -

John David Hawkins

STUDIA ASIANA – 9 – STUDIA ASIANA Collana fondata da Alfonso Archi, Onofrio Carruba e Franca Pecchioli Daddi Comitato Scientifico Alfonso Archi, Fondazione OrMe – Oriente Mediterraneo Amalia Catagnoti, Università degli Studi di Firenze Anacleto D’Agostino, Università di Pisa Rita Francia, Sapienza – Università di Roma Gianni Marchesi, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna Stefania Mazzoni, Università degli Studi di Firenze Valentina Orsi, Università degli Studi di Firenze Marina Pucci, Università degli Studi di Firenze Elena Rova, Università Ca’ Foscari – Venezia Giulia Torri, Università degli Studi di Firenze Sacred Landscapes of Hittites and Luwians Proceedings of the International Conference in Honour of Franca Pecchioli Daddi Florence, February 6th-8th 2014 Edited by Anacleto D’Agostino, Valentina Orsi, Giulia Torri firenze university press 2015 Sacred Landscapes of Hittites and Luwians : proceedings of the International Conference in Honour of Franca Pecchioli Daddi : Florence, February 6th-8th 2014 / edited by Anacleto D'Agostino, Valentina Orsi, Giulia Torri. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2015. (Studia Asiana ; 9) http://digital.casalini.it/9788866559047 ISBN 978-88-6655-903-0 (print) ISBN 978-88-6655-904-7 (online) Graphic design: Alberto Pizarro Fernández, Pagina Maestra Front cover photo: Drawing of the rock reliefs at Yazılıkaya (Charles Texier, Description de l'Asie Mineure faite par ordre du Governement français de 1833 à 1837. Typ. de Firmin Didot frères, Paris 1839, planche 72). The volume was published with the contribution of Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze. Peer Review Process All publications are submitted to an external refereeing process under the responsibility of the FUP Editorial Board and the Scientific Committees of the individual series. -

The Syrian Civil War a New Stage, but Is It the Final One?

THE SYRIAN CIVIL WAR A NEW STAGE, BUT IS IT THE FINAL ONE? ROBERT S. FORD APRIL 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-8 CONTENTS * SUMMARY * 1 INTRODUCTION * 3 BEGINNING OF THE CONFLICT, 2011-14 * 4 DYNAMICS OF THE WAR, 2015-18 * 11 FAILED NEGOTIATIONS * 14 BRINGING THE CONFLICT TO A CLOSE * 18 CONCLUSION © The Middle East Institute The Middle East Institute 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. 20036 SUMMARY Eight years on, the Syrian civil war is finally winding down. The government of Bashar al-Assad has largely won, but the cost has been steep. The economy is shattered, there are more than 5 million Syrian refugees abroad, and the government lacks the resources to rebuild. Any chance that the Syrian opposition could compel the regime to negotiate a national unity government that limited or ended Assad’s role collapsed with the entry of the Russian military in mid- 2015 and the Obama administration’s decision not to counter-escalate. The country remains divided into three zones, each in the hands of a different group and supported by foreign forces. The first, under government control with backing from Iran and Russia, encompasses much of the country, and all of its major cities. The second, in the east, is in the hands of a Kurdish-Arab force backed by the U.S. The third, in the northwest, is under Turkish control, with a mix of opposition forces dominated by Islamic extremists. The Syrian government will not accept partition and is ultimately likely to reassert its control in the eastern and northwestern zones. -

The Plight of Palestinian Refugees in Syria in the Camps South of Damascus by Metwaly Abo Naser, with the Support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill

Expert Analysis January 2017 Syrian voices on the Syrian conflict: The plight of Palestinian refugees in Syria in the camps south of Damascus By Metwaly Abo Naser, with the support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill Introduction: the historical role of Palestinians the Oslo Accords in 1992 and the resulting loss by both the in Syria Palestinian diaspora in general and the inhabitants of the After they took refuge in Syria after the 1948 war, al-Yarmouk refugee camp in particular of their position as Palestinians refugees were treated in the same way as a key source of both material and ideological support for other Syrian citizens. Their numbers eventually reached the Palestinian armed revolution in the diaspora. This was 450,000, living mostly in 11 refugee camps throughout Syria due in part to the failure of the various Palestinian national (UNRWA, 2006). Permitted to fully participate in the liberation factions to identify new ways of engaging the economic and social life of Syrian society, they had the diaspora – including the half million Palestinians living in same civic and economic rights and duties as Syrians, Syria – in the Palestinian struggle for the liberation of the except that they could neither be nominated for political land occupied by Israel. office nor participate in elections. This helped them to feel that they were part of Syrian society, despite their refugee This process happened slowly. After the Israeli blockade of status and active role in the global Palestinian liberation Lebanon in 1982, the Palestinian militant struggle declined. struggle against the Israeli occupation of their homeland. -

Aramaeans Outside of Syria 1. Assyria Martti Nissinen 1. Aramaeans

CHAPTER NINE OUTLOOK: ARAMAEANS OUTSIDE OF SYRIA 1. Assyria Martti Nissinen 1. Aramaeans and the Neo-Assyrian Empire (934–609 B.C.)1 Encounters between the Aramaeans and the Assyrians are as old as is the occupation of these two ethnic entities in the area between the Tigris and the Khabur rivers and in northern Mesopotamia. The first occurrence of the word ar(a)māyu in the Assyrian records is to be found in the inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser I (1114–1076 B.C.), who gives an account of his confronta- tion with the “Aramaean Aḫlamaeans” (aḫlamû armāya) along the Middle Euphrates;2 however, the presence of the Aramaean tribes in this area is considerably older.3 The Assyrians had governed the Khabur Valley in the 13th century already, but the movement of the Aramaean tribes from the west presented a constant threat to the Assyrian supremacy in the area. Tiglath-Pileser I and his follower, Aššur-bēl-kala (1073–1056 B.C.), fought successfully against the Aramaeans, but in the long run, the Assyrians were not able to maintain control over the Lower Khabur–Middle Euphrates region. Assur-dān (934–912 B.C.) and Adad-nirari II (911–891 B.C.) man- aged to regain the area between the Tigris and the Khabur occupied by the Aramaeans, but the Khabur Valley was never under one ruler, and even the campaigns of Assurnasirpal II (883–859 B.C.) did not consolidate the Assyrian dominion. Under Shalmaneser III (858–824 B.C.) the area east of the Euphrates came under Assyrian control, but it was not until the 1 I would like to thank the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ, USA) for the opportunity of writing this article during a research visit in May–June, 2011. -

Pre-Publication Proof

Contents List of Figures and Tables vii Preface xi List of Contributors xiii proof Introduction: Long-Distance Communication and the Cohesion of Early Empires 1 K a r e n R a d n e r 1 Egyptian State Correspondence of the New Kingdom: T e Letters of the Levantine Client Kings in the Amarna Correspondence and Contemporary Evidence 10 Jana Myná r ̌ová Pre-publication 2 State Correspondence in the Hittite World 3 2 Mark Weeden 3 An Imperial Communication Network: T e State Correspondence of the Neo-Assyrian Empire 64 K a r e n R a d n e r 4 T e Lost State Correspondence of the Babylonian Empire as Ref ected in Contemporary Administrative Letters 94 Michael Jursa 5 State Communications in the Persian Empire 112 Amé lie Kuhrt Book 1.indb v 11/9/2013 5:40:54 PM vi Contents 6 T e King’s Words: Hellenistic Royal Letters in Inscriptions 141 Alice Bencivenni 7 State Correspondence in the Roman Empire: Imperial Communication from Augustus to Justinian 172 Simon Corcoran Notes 211 Bibliography 257 Index 299 proof Pre-publication Book 1.indb vi 11/9/2013 5:40:54 PM Chapter 2 State Correspondence in the Hittite World M a r k W e e d e n T HIS chapter describes and discusses the evidence 1 for the internal correspondence of the Hittite state during its so-called imperial period (c. 1450– 1200 BC). Af er a brief sketch of the geographical and historical background, we will survey the available corpus and the generally well-documented archaeologi- cal contexts—a rarity among the corpora discussed in this volume.