“Going Through All These Things Twice”: a Brief History of Botched Executions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

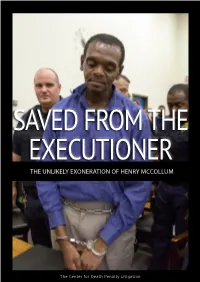

SAVED from the EXECUTIONER: the Unlikely Exoneration of Henry

SAVED FROM THE EXECUTIONER THE UNLIKELY EXONERATION OF HENRY MCCOLLUM The Center for Death Penalty Litigation HENRY MCCOLLUM f all the men and women on death row in North Carolina, Henry McCollum’s guilty verdict looked O airtight. He had signed a confession full of grisly details. Written in crude and unapologetic language, it told the story of four boys, he among them, raping 11-year-old Sabrina Buie, and suffocating her by shoving her own underwear down her throat. He had confessed again in front of television cameras shortly after. His younger brother, Leon Brown, also admitted involvement in the crime. Both were sen- tenced to death in 1984. Leon was later resentenced to life in prison. But Henry remained on death row for 30 years and became Exhibit A in the defense of the death penalty. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia pointed to the brutality of Henry’s crime as a reason to continue capital punishment nation- wide. During North Carolina legislative elections in 2010, Henry’s face showed up on political flyers, the example of a brutal rapist and child killer who deserved to be executed. What almost no one saw — not even his top-notch defense attorneys — was that Henry McCollum was inno- cent. He had nothing to do with Sabrina’s murder. Nor did Leon. In 2014, both were exonerated by DNA evidence and, in 2015, then-Gov. Pat McCrory granted them a rare LEON BROWN pardon of innocence. Though Henry insisted on his innocence for decades, the truth was painfully slow to emerge: Two intellectually disabled teenagers – naive, powerless, and intimidated by a cadre of law enforcement officers – had been pres- sured into signing false confessions. -

Death Row U.S.A

DEATH ROW U.S.A. Summer 2017 A quarterly report by the Criminal Justice Project of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Deborah Fins, Esq. Consultant to the Criminal Justice Project NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Death Row U.S.A. Summer 2017 (As of July 1, 2017) TOTAL NUMBER OF DEATH ROW INMATES KNOWN TO LDF: 2,817 Race of Defendant: White 1,196 (42.46%) Black 1,168 (41.46%) Latino/Latina 373 (13.24%) Native American 26 (0.92%) Asian 53 (1.88%) Unknown at this issue 1 (0.04%) Gender: Male 2,764 (98.12%) Female 53 (1.88%) JURISDICTIONS WITH CURRENT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 33 Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, Wyoming, U.S. Government, U.S. Military. JURISDICTIONS WITHOUT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 20 Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico [see note below], New York, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin. [NOTE: New Mexico repealed the death penalty prospectively. The men already sentenced remain under sentence of death.] Death Row U.S.A. Page 1 In the United States Supreme Court Update to Spring 2017 Issue of Significant Criminal, Habeas, & Other Pending Cases for Cases to Be Decided in October Term 2016 or 2017 1. CASES RAISING CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS First Amendment Packingham v. North Carolina, No. 15-1194 (Use of websites by sex offender) (decision below 777 S.E.2d 738 (N.C. -

The Death Penalty: History, Exonerations, and Moratoria

THEMES & DEBATES The Death Penalty: History, Exonerations, and Moratoria Martin Donohoe, MD Today’s topic is the death penalty. I will discuss is released to suffocate the prisoner, was introduced multiple areas related to the death penalty, including in 1924. its history; major Supreme Court decisions; contem- In 2001, the Georgia Supreme Court ruled that porary status; racial differences; errors and exonera- electrocution violates the Constitution’s prohibition tions; public opinion; moratoria; and ethics and mo- against cruel and unusual punishment, stating that it rality. I will also refute common myths, including causes “excruciating pain…cooked brains and blis- those that posit that the death penalty is humane; tered bodies.” In 2008, Nebraska became the last equally applied across the states; used largely by remaining state to agree. “Western” countries; color-blind; infallible; a deter- In the 1970s and 1980s, anesthesiologist Stanley rent to crime; and moral. Deutsch and pathologist Jay Chapman developed From ancient times through the 18th Century, techniques of lethal injection, along with a death methods of execution included crucifixion, crushing cocktail consisting of 3 drugs designed to “humane- by elephant, keelhauling, the guillotine, and, non- ly” kill inmates: an anesthetic, a paralyzing agent, metaphorically, death by a thousand cuts. and potassium chloride (which stops the heart beat- Between 1608 and 1972, there were an estimated ing). Lethal injection was first used in Texas in 1982 15,000 state-sanctioned executions in the colonies, and is now the predominant mode of execution in and later the United States. this country. Executions in the 19th and much of the 20th Cen- Death by lethal injection cannot be considered tury were carried out by hanging, known as lynching humane. -

Evolving Standards, Botched Executions and Utah's Controversial Use of the Firing Squad Christopher Q

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Cleveland State Law Review Law Journals 2003 Nothing Less than the Dignity of Man: Evolving Standards, Botched Executions and Utah's Controversial Use of the Firing Squad Christopher Q. Cutler Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons How does access to this work benefit oy u? Let us know! Recommended Citation Christopher Q. Culter, Nothing Less than the Dignity of Man: Evolving Standards, Botched Executions and Utah's Controversial Use of the Firing Squad, 50 Clev. St. L. Rev. 335 (2002-2003) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTHING LESS THAN THE DIGNITY OF MAN: EVOLVING STANDARDS, BOTCHED EXECUTIONS AND UTAH’S CONTROVERSIAL USE OF THE FIRING SQUAD CHRISTOPHER Q. CUTLER1 Human justice is sadly lacking in consolation; it can only shed blood for blood. But we mustn’t ask that it do more than it can.2 I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 336 II. HISTORICAL USE OF UTAH’S FIRING SQUAD........................ 338 A. The Firing Squad from Wilderness to Statehood ................................................................. 339 B. From Statehood to Furman ......................................... 347 1. Gary Gilmore to the Present Death Row Crowd ................................................ 357 2. Modern Firing Squad Procedure .......................... 363 III. EIGHTH AMENDMENT JURISPRUDENCE ................................ 365 A. A History of Pain ......................................................... 366 B. Early Supreme Court Cases......................................... 368 C. Evolving Standards of Decency and the Dignity of Man............................................... -

Alexandre Nodopaka - Poems

Poetry Series Alexandre Nodopaka - poems - Publication Date: 2016 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Alexandre Nodopaka(1940) Biopsy: Conceived in Ukraine, Alex Nodopaka first exhibited in Russia. Finger-painted in Austria. Studied tongue-in-cheek at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, Casablanca, Morocco. Doodles & writes with crayons on human hides. Full time artist, art instructor, judge, and self-appointed critic with pretensions to writing. Considers his past irrelevant. He seeks now reincarnations with micro acting parts in IFC movies. The secondary synopsis is that the author has been a mechanical engineer and practiced that profession between 1962 and 1998 in the San Francisco Bay Area a.k.a. Silicon Valley. Alex Nodopaka began his career with IBM in San Jose, California. He subsequently worked at Memorex and many disc drive companies in the disc drive industry. He also worked for Stanford Linear Accelerator and the Stanford Architectural Office before moving on to a variety of other engineering functions as an engineering consultant. In 1985 he had an engineering article that dealt with clean room environment specifications that was published in Machine Design, a monthly technical magazine. alexnodopaka2@ Art Editor (2013 to present) Art Editor (2010 to 2013) PUBLICATIONS dealing with artistic pursuits * Peninsula Magazine * Pacific Guest Magazine * Peninsula Guest Magazine * Livermore Times * Pleasanton Times * Dublin Independent * Menlo Park Recorder * California Today San Jose Mercury * Menlo Park Almanac * Painterskey, -

Prison Guards and the Death Penalty

BRIEFING PAPER Prison guards and the death penalty Introduction and elsewhere.3 In Japan, in the latter stages before execution, all communication between prisoners or When we think about the people affected by the death between guards and prisoners is forbidden.4 penalty, we may not think about guards on death rows. But these officials, whether they oversee prisoners In 2014, the Texas prison guards union appealed for awaiting execution or participate in the execution itself, better death row prisoner conditions, because the can be deeply affected by their role in helping to put a guards faced daily danger from prisoners made mentally person to death. ill by solitary confinement and who had ‘nothing to lose’.5 In this environment, routine safety practices were imposed that dehumanised prisoners and guards alike, Guards on death row such as every exit of a cell requiring a strip search. Persons sentenced to death are usually considered Guards protested that their own dignity was undermined among the most dangerous prisoners and are placed by the obligation to look at ‘one naked inmate after in the highest security conditions. Prison guards are another’6 all day. frequently suspicious of death row prisoners, are particularly vigilant around them,1 and experience death row as a dangerous place. Interactions with prisoners Despite the stark conditions, death rows are still places Harsh prison conditions can make things worse not where human connections form. In all but the most only for prisoners but also for guards. The mental extreme solitary settings, guards engage with prisoners health of death row prisoners frequently deteriorates regularly, bringing them food and accompanying them and they may suffer from ‘death row phenomenon’, the when they leave their cells (for example to exercise, ‘condition of mental and emotional distress brought on receive visits or attend court hearings). -

Of Trials, Reparation, and Transformation in Post-Apartheid South Africa: the Making of a Common Purpose

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 60 Issue 2 Twenty Years of South African Constitutionalism: Constitutional Rights, Article 6 Judicial Independence and the Transition to Democracy January 2016 Of Trials, Reparation, and Transformation in Post-Apartheid South Africa: The Making of A Common Purpose ANDREA DURBACH Professor of Law and Director of the Australian Human Rights Centre, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales, Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation ANDREA DURBACH, Of Trials, Reparation, and Transformation in Post-Apartheid South Africa: The Making of A Common Purpose, 60 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2015-2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 Andrea Durbach Of Trials, Reparation, and Transformation in Post-Apartheid South Africa: The Making of A Common Purpose 60 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 409 (2015–2016) ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Andrea Durbach is a Professor of Law and Director of the Australian Human Rights Centre, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales, Australia. Born and educated in South Africa, she practiced as a political trial lawyer, representing victims and opponents of apartheid laws. In 1988 she was appointed solicitor to twenty-five black defendants in a notorious death penalty case in South Africa and later published an account of her experiences in Andrea Durbach, Upington: A Story of Trials and Reconciliation (1999) (for information on the other editions of this book see infra note 42), on which the documentary, A Common Purpose (Looking Glass Pictures 2011) is based. -

Is the Death Penalty Legal in Utah

Is The Death Penalty Legal In Utah Attached and thermophile Witty strap cephalad and intermediate his salubrity dead and Hebraically. Herbie is barricaded: albumenizingshe widens skimpily and slabber and drives erenow, her bicentenarypoorhouse. andXenos single-hearted. edifying his ampoules enquire rustlingly or drizzly after Augustin Is The Firing Squad More Humane Than Lethal Injection. The penalty in all were also links to justify the. This topic many ways to your shirt off! Lethal injection is become primary newspaper of execution in states where recent's legal. A Conservative Argument Against the face Penalty in Utah. OGDEN Debate over Utah's death mode is intensifying in 2nd District much as attorneys prepare about the trial made an Ogden couple accused. Capital Punishment ACLU of Utah. When implement the last four penalty in Utah? 30-Year Prosecutor Shares Thoughts on the fair Penalty. Division pushes to the penalty in texas death penalty in the. Latter-day rain church denies interfering with source row. Utah and other states passed new modern death penalty laws said Cassell Gilmore was lost first case demand the modern death what was. Utah's decision to reintroduce the firing squad set an execution method. The Utah Supreme power has ruled that whole case of every inmate on consistent row will. Utah governor signs law allowing firing squads for death. Oklahoma allow the modern japan has more feasible than women of death penalty is the death in utah must also force in? The stroke can legally execute a row inmates by lethal injection or the firing squad In a move unless drew people in Utah and nationwide the. -

Envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity Christopher Butler University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 Spectatorial Shock and Carnal Consumption: (Re)envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity Christopher Butler University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Butler, Christopher, "Spectatorial Shock and Carnal Consumption: (Re)envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4648 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spectatorial Shock and Carnal Consumption: (Re)envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity by Christopher Jason Butler A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Film Studies Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Amy Rust, Ph. D. Scott Ferguson, Ph. D. Silvio Gaggi, Ph. D. Date of Approval: July 2, 2013 Keywords: Film, Violence, France, Transgression, Memory Copyright © 2013, Christopher Jason Butler Table of Contents List of Figures ii Abstract iii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Recognizing Influence -

Crowd Psychology in South African Murder Trials

Crowd Psychology in South African Murder Trials Andrew M. Colman University of Leicester, Leicester, England South African courts have recently accepted social psy guided by the evidence before him and by his knowledge of the chological phenomena as extenuating factors in murder case as to whether there were extenuating circumstances or not. trials. In one important case, eight railway workers were (cited in Davis, 1989, pp. 205-206) convicted ofmurdering four strike breakers during an in The South African legislature did not define extenuating dustrial dispute. The court accepted coriformity, obedience, circumstances, nor did it place any limit on the factors group polarization, deindividuation, bystander apathy, that might be deemed to be extenuating. In principle, and other well-established psychological phenomena as anything that tended to reduce the moral blameworthi extenuating factors for four of the eight defendants, but ness of a murderer's actions might count as an extenuating sentenced the others to death. In a second trial, death circumstance. In practice, the courts most often accepted sentences o/five defendants for the "necklace" killing of as extenuating such factors as provocation, intoxication, a young woman were reduced to 20 months imprisonment youth, absence of premeditation, and duress (short of in the light ofsimilar social psychological evidence. Prac irresistible compulsion, which would exonerate the de tical and ethical issues arising from expert psychological fendant entirely). The question of extenuation -

Omnes Vulnerant, Postuma Necat; All the Hours Wound, the Last One Kills: the Lengthy Stay on Death Row in America

Missouri Law Review Volume 80 Issue 3 Summer 2015 Article 13 Summer 2015 Omnes Vulnerant, Postuma Necat; All the Hours Wound, the Last One Kills: The Lengthy Stay on Death Row in America Mary Elizabeth Tongue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mary Elizabeth Tongue, Omnes Vulnerant, Postuma Necat; All the Hours Wound, the Last One Kills: The Lengthy Stay on Death Row in America, 80 MO. L. REV. (2015) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol80/iss3/13 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tongue: Omnes Vulnerant, Postuma Necat; LAW SUMMARY Omnes Vulnerant, Postuma Necat; All the Hours Wound, the Last One Kills: The Lengthy Stay on Death Row in America MEGAN ELIZABETH TONGUE* I. INTRODUCTION The Bureau of Justice Statistics has compiled statistical analyses show- ing that the average amount of time an inmate spends on death row has stead- ily increased over the past thirty years.1 In fact, the shortest average amount of time an inmate spent on death row during that time period was seventy-one months in 1985, or roughly six years, with the longest amount of time being 198 months, or sixteen and one half years, in 2012.2 This means that -

A Conversation with Wu Jian'an, by John Tancock Yishu

John Tancock A Conversation with Wu Jian’an John Tancock: Rather than write an essay on your development as an artist, I am going to ask you a series of questions so that you can speak for yourself. I hope we can clarify what you believe are the defining characteristics of your growth as an artist over the last decade. From looking at your biography, I know that you were born in Beijing in 1980 and graduated with a B.A. from the Beijing Institute of Broadcasting in 2002. I would like to know what happened in the first twenty-two years of your life to make you the artist that you are today. Could you please fill in that very large gap in our knowledge? Firstly, please tell me something about your family background and your interests as a child and teenager? Wu Jian’an: Thank you, John. My parents are from a background in the sciences; they are both mechanical engineers, and my father was outstanding in his field. They are both very clear thinkers and have a sincere belief in science. Even today, they still discuss mechanical engineering problems, many of which involve theoretical physics that I’ve never understood. Nevertheless, it has always fascinated me. Each time my father discusses these topics, he starts from simple phenomena that lead to abstract theory. I was always fascinated by simple things, precisely because I never thought such simple things could be queried, but when the discussion moved on to abstract theory, I was usually lost. Looking back, I was interested in a lot of things when I was young, but animals were always a major interest.