Construction of Gender Through Fashion and Dressing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dolls in Tunics & Teddies in Togas

AIA Education Department Dolls in Tunics: Procedures Lesson Plans Dolls in Tunics & Teddies in Togas: A Roman Costume Project Sirida Graham Terk The Archer School for Girls Los Angeles, California Acknowledgements: Silvana Horn and Sue Sullivan origi- pertinent dress and status information, rather than require nated this project with the seventh-grade students of The research. S/he can give older students increased respon- Archer School for Girls in Los Angeles, California. It has sibility for research and hold them to higher standards of been refined and expanded over many years with the help costume quality and authenticity. High-school students and feedback of Theatre Arts teacher Emily Colloff, Archer can clothe bears as awards for younger students or as chari- students, and participants in the 2007 AIA Teacher Work- table donations, or create life-size garments for wearing to shop in San Diego. We appreciate the efforts and useful a Roman Feast (see the AIA lesson plan entitled Reclining suggestions of both educators and pupils! and Dining: A Greco-Roman Feast) or to Junior Classical League conventions. Overview Students research Roman dress and create small-scale ver- Goals sions of clothing for cloth dolls or teddy bears in this two- While students should become comfortable identifying, phase project, especially suited to a Latin or History class. producing, and handling items of Roman costume (or those We provide explicit instructions about materials, patterns, of another chosen culture), the primary goal is to learn how and techniques to make the teacher’s effort less daunting. clothing and accoutrements communicate age, gender, job, Students first learn about Roman dress and collect informa- and status within a society. -

Garden Fresh Salads Appetizers

APPETIZERS Chips & Dips Our crispy tortilla chips with your choice of dip. Salsa - 4 Fresh Guacamole - 8 Creamy Queso - 7 (Add Taco Meat or Pico de Gallo for 1.50 each) Spinach & Artichoke 8 Crispy corn tortilla chips with creamy spinach artichoke dip. Triple Dipper 11 Corn chips with salsa, queso & guacamole. Triple Dipper (Add artichoke for 3.00) Onion Rings 6 Hand breaded made to order. Cheese Sticks 8 Made fresh served with marinara. Fried Mushrooms 8 Crispy battered with side of honey mustard. Macho Nachos Tortilla chips topped with cheddar jack cheese, pinto beans, Buffalo Wings 9 sour cream and black bean corn pico. Jumbo traditional wings seasoned in our house rub, tossed Taco Meat or Fajita Chicken - 9 Fajita Beef - 11 in your choice of Honey BBQ or Buffalo Sauce. Served with (Add jalapenos and guacamole for additional charge) Ranch or Bleu Cheese dressing. Stuffed Avocado 8 Fresh avocado, chicken and monterey jack cheese in crispy breading. Served on a bed of rice. Pulled Pork Quesadillas 10 Tortilla stuffed with our tender, Carolina Style pulled pork and cheddar jack cheese. Southwest Quesadillas - Chicken 9 Beef 11 Tortilla stuffed with cheddar jack cheese, fajita meat and black bean corn pico. Macho Nachos GARDEN FRESH SALADS Dressings: Ranch, Jalapeno Ranch, Roasted Garlic Balsamic Vinaigrette, Thousand Island, Honey Mustard, Vidalia Onion & Bacon, Bleu Cheese and Strawberry Vinaigrette. Soup & Salad 7 Your choice of a House or Caesar side salad and a cup of our potato or green chile soup. Avocado Cobb Salad 10 NO CROUTONS Candied Pecan Mixed greens, fresh avocado, cheddar jack cheese, eggs, Strawberry Salad tomatoes, bacon bits, croutons and charbroiled chicken breast. -

1 Centro Vasco New York

12 THE BASQUES OF NEW YORK: A Cosmopolitan Experience Gloria Totoricagüena With the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre TOTORICAGÜENA, Gloria The Basques of New York : a cosmopolitan experience / Gloria Totoricagüena ; with the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre. – 1ª ed. – Vitoria-Gasteiz : Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia = Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, 2003 p. ; cm. – (Urazandi ; 12) ISBN 84-457-2012-0 1. Vascos-Nueva York. I. Sarriugarte Doyaga, Emilia. II. Renteria Aguirre, Anna M. III. Euskadi. Presidencia. IV. Título. V. Serie 9(1.460.15:747 Nueva York) Edición: 1.a junio 2003 Tirada: 750 ejemplares © Administración de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco Presidencia del Gobierno Director de la colección: Josu Legarreta Bilbao Internet: www.euskadi.net Edita: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia - Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco Donostia-San Sebastián, 1 - 01010 Vitoria-Gasteiz Diseño: Canaldirecto Fotocomposición: Elkar, S.COOP. Larrondo Beheko Etorbidea, Edif. 4 – 48180 LOIU (Bizkaia) Impresión: Elkar, S.COOP. ISBN: 84-457-2012-0 84-457-1914-9 D.L.: BI-1626/03 Nota: El Departamento editor de esta publicación no se responsabiliza de las opiniones vertidas a lo largo de las páginas de esta colección Index Aurkezpena / Presentation............................................................................... 10 Hitzaurrea / Preface......................................................................................... -

Lunettes: 1234.Les Grands Noms, Le Grand Choix, Les Petitsprix

Gagnetes places pour le match Luxembourg-Russie (voirp.30) Un pas de plus vers la LUNDI 7 OCTOBRE 2013 N°1380 fin du secret bancaire Luxembourg 6 Lors du discours sur l'état de la Na- de gouvernement ont adopté un projet Ils étaient 1 250 à courir tion, le Premier ministre, Jean-Claude de loi et quatre règlements grand-du- contre le cancer du sein Juncker (CSV), avait annoncé la fin caux pour faciliter les procédures programmée du secret bancaire. Ven- d'échanges automatiques des données dredi, les ministres réunis en Conseil bancaires notamment. PAGE 5 ...................................................................................................................................................... Vettel triomphe devant les Lotus Économie 12 Colruyt veut poursuivre sa stratégie d'expansion People 20 Jennifer Lawrence a dû maigrir pour réussir Météo 36 Sebastian Vettel, très satisfait par sa nouvelle victoire devant les Lotus de Kimi Räikkönen (à g.) et de Romain Grosjean (à d.). L'Allemand Sebastian Vettel rée, devant les deux Lotus-Re- victoire cette saison et conforte MATIN APRÈS-MIDI (Red Bull-Renault), triple cham- nault du Finlandais Kimi Räik- sa première place avec 77 points pion du monde en titre, a rem- könen et du Français Romain d'avance sur Fernando Alonso 9° 17° porté, hier, le Grand Prix de Co- Grosjean. Il a signé sa huitième (Ferrari), qui a terminé 6e. PAGE 33 2 Actu LUNDI 7 OCTOBRE 2013 / WWW.LESSENTIEL.LU Une fillette de Le Mettis a été inauguré 10 ans se pend BOBIGNY - Une enfant de 10 ans, scolarisée en CM2, est en grande pompe à Metz morte après s'être pendue au domicile. -

Close to the Skin: a Revealing Look at Lingerie

Close to the Skin: A Revealing look at Lingerie Wedding gown House of Worth, France ca. 1878 Silk faille; silk embroidery; glass pearls; lace #67.446 Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895) is considered the founder of haute couture. This early Worth creation illustrates his patronage by wealthy Americans, who had to travel to Paris to purchase their custom made dresses. Sarah Noyes Tibbets wore this dress when she married John Wool Griswold on January 15, 1878. Petticoat ca. 1878 Cotton #67.446c This petticoat was probably coordinated to go with the elaborate wedding gown by Charles Frederick Worth, made for Sarah Noyes Tibbett. The fineness of the cotton petticoat matches that of the gown. Pantaloons or drawers United States 1870s Plain weave light brown mixed fiber (silk, cotton, and/or wool) #57.920 Hoop skirt United States Ca. 1870 Steel springs; cotton twill tape No acc. # Hoop skirts could on occasion flip up, due to tripping or high wind. Pantaloons, or drawers, proved helpful in covering the legs if such a faux paus occurred. Corset R & G Corset Co. 1875-1900 White twill-weave cotton, lace, steel #67.591 Close to the Skin: A Revealing look at Lingerie Dress 1925-1930 Floral print silk chiffon with pink silk faille underdress. #59.379 Simpler, sheerer dresses in fashion in the 1920s often borrowed elements from undergarments. This example has a pink slip that is integral to the sheer overdress, including a matching printed hem that extends below the outer hemline. The edge of the wide collar is finished in a manner similar to fine lingerie. -

The Big Easy Languid Loungewear Surfaces This Season with Exotic Prints in Traditional Relaxed Shapes

VUITTON’S BROOKLYN NIGHT/4 LINGERIE BUSTS OUT ONLINE/10 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’MONDAY Daily Newspaperewspaper • April 7, 2008 2 • $2.00 Accessories/Innerwear/Legwearessorrieies/s/InInnenerwrweae The Big Easy Languid loungewear surfaces this season with exotic prints in traditional relaxed shapes. Here, Oscar de la Renta’s riff on a caftan that zips up the front. For more, see pages 6 and 7. Banana’s New Signature: Retailer Heads Upmarket With First Monogram Unit By Sharon Edelson NEW YORK — The road to the top is getting IES FROM BARBARA FLOOD’S CLOSET; FASHION ASSISTANT: DANIELLE SPONDER; STYLED BY BOBBI QUEEN DANIELLE SPONDER; STYLED BY ASSISTANT: FASHION CLOSET; FLOOD’S IES FROM BARBARA crowded — especially in that zone just above women’s specialty chains such as J. Crew and Ann Taylor. The latest to enter the fray is Banana Republic, which today will open its first freestanding store for the new limited edition BR Monogram collection. The line focuses on better fabrics and tailoring at prices about 30 to 40 percent higher than the brand’s core collection. The 3,000-square-foot BR Monogram store at 205 Bleecker Street and Sixth Avenue here was previously a Banana Republic unit. A spokeswoman said See Banana, Page14 PHOTO BY GEORGE CHINSEE; MODEL: ANIA/SUPREME; HAIR: DARIA WRIGHT FOR DARIAWRIGHT.COM; MAKEUP: MIZU FOR PRICE INC.; ALL ACCESSOR GEORGE CHINSEE; MODEL: ANIA/SUPREME; HAIR: DARIA WRIGHT FOR DARIAWRIGHT.COM; PHOTO BY 2 WWD, MONDAY, APRIL 7, 2008 WWD.COM Uneven Retail Employment Picture WWDMONDAY By Liza Casabona manufacturers in the world — “We expect somewhat of a yet they are being forced to lay transition in the retail sector as Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear WASHINGTON — Department off workers because of uncom- some businesses start to make stores cut jobs and specialty petitive U.S. -

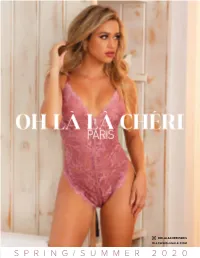

S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 0

OHLALACHERIPARIS OLLCWHOLESALE.COM SPRING/SUMMER 2020 1 We celebrate inSexy all shapes & sizes! Touches of flair inspire our fashion forwardFrench lingerie pieces creating the essence of Oh Là Là Chéri culture. The everlasting evolution of our collection is influenced by the blending of & alluringmarket trends.romantic 2 3 EVETTE 2 PC SET Standard & Plus Size Floral Soft Cup Halter Bra with Matching High Waist Panty and Functional Front Zipper 40-11127 / 40-11127X S/M - L/XL / 1X/2X Heather Rose EVETTE TEDDY Standard & Plus Size Floral Soft Cup Teddy with Functional Front Zipper 52-11127 / 52-11127X S/M - L/XL / 1X/2X Heather Rose VETTE E4 5 AVAILABLE BOXED AMATA 2 PC SET Standard Size Only Embroidered High Neckline Bra with Appliqué Detail & High Waisted Open Back Panty 40-11215 S/M - L/XL Black AVAILABLE BOXED AMATA TEDDY Standard Size Only Embroidered High Neckline Teddy with Appliqué Detail & Open Back 51-11215 S/M - L/XL Black MATA A6 7 ILA 3 PC SET Standard Size Unlined Eyelash Bra with Matching Garterbelt and G-String 41-11128 S - M - L - XL Heather Rose ILA 3 PC SET Standard Size Unlined Eyelash Bra with Matching Garterbelt and G-String 41-11128 S - M - L - XL Black LA I8 9 CHERYL TEDDY Standard Size High Leg Soft Cup Teddy with Open Side & Functional Waist Ties 52-11217 S/M - L/XL Potent Purple/Mauve Black AVAILABLE BOXED ALLISON TEDDY Standard & Plus Size Soft Lace Collared Teddy with Front Keyhole And Open Back 52-10716 / 52-10716X S/M - L/XL / 1X/2X - 3X/4X Mauve Shadows Black HERYL C10 11 MACKENZIE 2 PC SET Standard Size -

COLORS Glitter Sneakers Signature Silk Slip Dress White Button Lipstick Down BRAND GEL POLISH

PARTY READY • HOLIDAY 2021 169 COLORS Glitter Sneakers Signature Silk Slip Dress White Button Lipstick Down BRAND GEL POLISH Cream Puff White Wedding White Button Lady Lilly Studio White Bouquet Naked Naiveté Satin Slippers Mover & Shaker Ice Bar Negligee Down Romantique Pointe Blanc Beau Aurora Winter Glow Unlocked Clearly Pink Uncovered Unmasked Grapefruit Soft Peony Bare Chemise Baby Smile Sparkle Rule Breaker Pink Pursuit Salmon Run Jellied Glitter Sneakers Exquisite Bellini Powder My Nose Wrapped in Sweet Cider Satin Pajamas Flowerbed Folly Chandelier Linen Boheme Iced Cappuccino Clay Canyon Self-Lover Silk Slip Dress Gala Girl Cashmere Wrap Field Fox Nude Knickers Radiant Chill Tundra Fragrant Freesia Candied Be Demure Blushing Topaz Blush Teddy Strawberry Lavender Lace Beckoning Mauve Maverick Coquette Cake Pop Pacifi c Rose Rose Bud Kiss From A Gotcha Smoothie Begonia Rose Holographic Married To The Wooded Bliss Fuji Love Untitled Bronze Sultry Sunset Rooftop Hop Magenta Mischief Tutti Frutti Hot Pop Pink Ecstasy Pink Bikini Museum Meet Mauve Cute Pink Leggings Offbeat Lobster Roll Jelly Bracelet Charm Tropix Beach Escape Sparks Fly Desert Poppy Uninhibited Catch Of The B-Day Candle Mambo Beat Day Soulmate Hollywood Liberté Sangria At Femme Fatale Kiss The Skipper Element Kiss Of Fire Wildfi re Hot Or Knot Soft Flame Devil Red First Love Sunset Hot Chilis Bordeaux Babe Books & Brick Knit Company Red Tartan Punk Rose Brocade Red Baroness Ripe Guava Ruby Ritz Garnet Glamour How Merlot Rouge Rite Beaujolais Rebellious Ruby Decadence -

Full Clothing Lists.Xlsx

Detailed Clothing List - Alphabetically By Brand Brand Season Item Type Gender Detail 2000 Gymboree N/A Bodysuit Boys Green or red with wheel-shaped zipper pull N/A Pants N/A Fleece pants with cord lock in blue, red, green or gray with gray elastic waistband and "Gymboree" on back pocket 21 Pro USA N/A Hooded Sweatshirts N/A Pullover & zip styles. RN#92952 2b REAL N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Girls Velour, zip front wth "Major Diva" printed on front A.P.C.O. N/A Hooded Sweatshirts N/A Navy or burgundy; "Artic Zone" is printed on front abcDistributing N/A Jacket/Pant Set N/A Fleece, pink or royal blue with waist drawstring; may say "Princess" or "Angel" on it Academy N/A Pajama Pants and Boxers Both Pull-on pants for boys and girls and boxers for girls - see recall for details Active Apparel N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Boys Zipper hooded sweatshirt Adio N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Boys Zip fleece, white with blue stripes and red panels on sides. Adio on front Aeropostale N/A Hooded jackets/sweatshirts N/A Multiple brands and models - see recall Agean N/A Robes Both Variety of colors; wrap style with waist belt, two front patch pockets and hood Akademiks N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Girls 4 styles - see recall All Over Skaters N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Boys With padlocks, skaters or black with imprint Almar Sales Company N/A Watches N/A Clear plastic watches with white snaps; bands have clear, glitter-filled liquid and colored liquid inside, including pink, blue, red and yellow. -

Vendor List Fort Valley State University

Vendor List Fort Valley State University 4imprint Inc. Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce Street Oshkosh, WI 54901 [email protected] www.4imprint.com Contracts: Internal Usage - Effective Standard - Effective Aliases : Bemrose - DBA Nelson Marketing - FKA Products : Accessories - Backpacks Accessories - Convention Bag Accessories - Luggage tags Accessories - purse, change Accessories - Tote Accessories - Travel Bag Crew Sweatshirt - Fleece Crew Domestics - Cloth Domestics - Table Cover Electronics - Earbuds Electronics - Flash Drive Gifts & Novelties - Button Gifts & Novelties - Key chains Gifts & Novelties - Koozie Gifts & Novelties - Lanyards Gifts & Novelties - Rally Towel Gifts & Novelties - tire gauge Golf/polo Shirts - Polo Shirt Headbands, Wristbands, Armband - Armband Home & Office - Dry Erase Sheets Home & Office - Fleece Blanket Home & Office - Mug Home & Office - Night Light Housewares - Coasters Housewares - Jar Opener Jackets / Coats - Coats - Winter Jackets / Coats - Jacket Jewelry - Lapel Pin Miscellaneous - Candy Miscellaneous - Cell Phone Accessory Item (wallet) Miscellaneous - Clips Miscellaneous - Cup Sleeve Miscellaneous - Magnets Miscellaneous - Mints Miscellaneous - Stress Ball Miscellaneous - Stress Ball Miscellaneous - Sunglasses Miscellaneous - Tablet Accessory Miscellaneous - Umbrella Miscellaneous - USB Charger Miscellaneous - USB Power Bank Office Products - Desk Caddy Paper Products - Tissue Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Desk Calendar Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Notepad 08/27/2018 Page 1 of -

Full Clothing Lists.Xlsx

Detailed Clothing List - Alphabetically By Brand Brand Season Item Type Gender Detail 21 Pro USA N/A Hooded Sweatshirts N/A Pullover & zip styles. RN#92952 Academy N/A Pajama Pants and Boxers Both Pull-on pants for boys and girls and boxers for girls - see recall for details Active Apparel N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Boys Zipper hooded sweatshirt Aeropostale N/A Hooded jackets/sweatshirts N/A Multiple brands and models - see recall Aegean Apparel F/W Pajama Pants & Robes N/A Fleece long sleeved cat print robe and cotton Santa print pajama pants. Akademiks N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Girls 4 styles - see recall All Over Skaters N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Boys With padlocks, skaters or black with imprint almirah N/APajama Sets N/A Two piece, short sleeved, long pant pajama sets from sizes 6 to 12 months through 10Y. Patterns include Acrofish Neon, Crab, Elephant, Jellyfish, Mooch, Monkey & Seahorse. Alpha Industries N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Boys Hooded , zippered sweatshirts, olive green with eagle on front and "Hero by Choice" and "Alpha" Alstyle N/A Onesies N/A The 100% cotton, short-sleeved bodysuits were sold in black, blue, pink and white. They have a lap shoulder construction with three-snap closure at the crotch. Amerex Group F/W Jacket Girls Faux cheetah fur jacket in sizes 12-24 months. American Apparel N/A Sleep sack Both 6-12 months in black, red, pink, light blue, gray, green, navy & white. American Eagle Outfitters N/A Pants/Jeans/Shorts Girls Toddler girls - various sizes Amy Byer N/A Hooded Jackets Girls Brown jacket with cargo pockets Apple Bottom N/A Hooded jackets/sweatshirts N/A Multiple brands and models - see recall Apple Park N/A Pajama Sets N/A Long sleeved shirt with full length pants ASHERANGEL N/A Nightgowns/Pajama Sets Girls Short sleeve nightgowns; two-piece long sleeve pajama sets - see recall for details Atico International F/W Slippers N/A Decorated with stuffed fabric figures including snowmen, Santa, reindeer, and penguins, and have decorative rattles inside the slippers that sound like bells when shaken. -

Comfort Teddy Knitting Pattern

Comfort Teddy Knitting Pattern What are Comfort Teddies? Teddies are a brilliant source of comfort for children. By working with people and services across Scotland, we are able to provide our Comfort Teddies to soothe children in distress. Comfort Teddies are hand-knitted in communities and carried by emergency services to be given to children in distressing situations. The teddies provide some immediate comfort for children, and also link families to ongoing support through Children 1st’s Parentline service. Materials Please use the materials specified and follow the pattern exactly. It has been created to meet EU toy safety standards to make sure your teddy is safe to give to children. Teddies must be made using SIRDAR Hayfield Bonus DK acrylic wool, in the following colour choices: 964 Oatmeal 960 Powder Blue 944 Cupid (pink) 977 Signal red 916 Emerald (green) 957 Primrose (yellow) 766 Pumpkin (mid brown) 981 Bright orange 221 Glitter - Tinseltown (Lilac) 947 Chocolate 965 Black Please do not use any mohair, angora, feathersoft, lurex or cotton yarn anywhere on the teddy as these often cause allergic reactions. You will need: For the knitting Mixed, bright colours for clothing and a separate colour for the body. Small amount of black or dark coloured yarn for stitching on the face. Size 11 (3mm) knitting needles. A stitch holder or large safety pin would be useful. For the stuffing Teddies must be stuffed using Trimits supersoft toy & cushion filling, 100% hi-loft polyester. There should be approximately 50 to 60 grams of filling per teddy. Knitting Pattern Key: Garter stitch: - all rows are knitted Stocking stitch: - one row knit, one row purl Pattern: Paws and trousers: Using main teddy colour cast on 10 stitches and proceed in garter stitch for 10 rows.