Gender Politics and the Walking Dead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

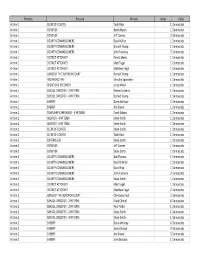

Inmate Roster

Current as of 10/1/2021 5:00:04 AM MCJ# Last Name First Name Date of Entry DOB 271848 ABON JONOC 1/18/2021 8/26/1984 305575 ADAMS CHRISTIAN 9/22/2021 4/17/1985 336676 ADAMS EVAN 12/4/2020 8/7/1992 378472 ALDRIDGE TORY 5/13/2020 5/15/1993 312579 ALERS ADALBERTO 3/26/2021 7/10/1988 208166 ALEXANDER JAMES 7/23/2021 12/27/1978 351411 ALEXANDER HARVEY 5/5/2021 3/16/1994 333236 ALEXANDER DVONTEA 4/21/2020 9/1/1992 238879 ALFARO ALBERTO 3/17/2021 9/12/1972 601619 ALI AHMED 8/4/2021 1/1/1995 601338 ALLEN ARTHUR 2/12/2021 4/19/1992 207397 ALLEN MATTHEW 7/29/2020 8/28/1975 377236 ALLEN SHAKUR 9/10/2021 2/20/1997 601628 ALMONTE JUAN 8/9/2021 1/21/1985 601716 ALVAREZ EDWIN 9/29/2021 8/24/1987 601452 ANDERSON AHMAD 5/9/2021 2/14/2002 600279 ANDERSON LAVOUNTAE 2/5/2021 7/22/2001 600466 ANDERSON JAMAL 9/1/2021 4/10/1981 220366 ANDERSON SCOTT 9/22/2021 2/23/1973 314916 ANDERSON BRANDON 12/30/2020 10/2/1989 304126 ANDERSON MATHEW 9/30/2021 8/22/1989 328380 ANDREWS SHYMEAR 9/1/2021 2/27/1990 241411 ANDUJAR MIGUEL 1/11/2021 5/22/1975 601500 ARIAS-CAMARENA JULIO 6/2/2021 5/9/1969 205162 ARMSTRONG MORICE 8/20/2021 3/18/1963 601416 ASHTON KIRK 4/14/2021 3/7/1970 219439 AVELIN JOHN 8/12/2021 11/2/1963 225512 AVILEZ EDDIE 4/30/2021 11/30/1982 601288 BACCHETTA NICHOLAS 6/24/2021 6/9/1989 601136 BAILEY MALIK 8/4/2021 2/25/1998 345177 BAKER THOMAS 9/4/2021 11/30/1987 376757 BALLOU KAMAL 2/1/2021 11/9/1992 230726 BARBER SHANNON 8/11/2021 7/24/1976 301191 BARBER RAY 4/16/2021 3/22/1989 355243 BARLEY JEREMIAH 6/12/2020 5/25/1994 331673 BARNES BENNIE 7/26/2021 7/21/1971 -

Misdemeanor Warrant List

SO ST. LOUIS COUNTY SHERIFF'S OFFICE Page 1 of 238 ACTIVE WARRANT LIST Misdemeanor Warrants - Current as of: 09/26/2021 9:45:03 PM Name: Abasham, Shueyb Jabal Age: 24 City: Saint Paul State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/05/2020 415 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFFIC-9000 Misdemeanor Name: Abbett, Ashley Marie Age: 33 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 03/09/2020 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Abbott, Alan Craig Age: 57 City: Edina State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 09/16/2019 500 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Disorderly Conduct Misdemeanor Name: Abney, Johnese Age: 65 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/18/2016 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Shoplifting Misdemeanor Name: Abrahamson, Ty Joseph Age: 48 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/24/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Trespass of Real Property Misdemeanor Name: Aden, Ahmed Omar Age: 35 City: State: Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 06/02/2016 485 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFF/ACC (EXC DUI) Misdemeanor Name: Adkins, Kyle Gabriel Age: 53 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/28/2013 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Aguilar, Raul, JR Age: 32 City: Couderay State: WI Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/17/2016 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Driving Under the Influence Misdemeanor Name: Ainsworth, Kyle Robert Age: 27 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 11/22/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Theft Misdemeanor ST. -

The Walking Dead

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA1080950 Filing date: 09/10/2020 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91217941 Party Plaintiff Robert Kirkman, LLC Correspondence JAMES D WEINBERGER Address FROSS ZELNICK LEHRMAN & ZISSU PC 151 WEST 42ND STREET, 17TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10036 UNITED STATES Primary Email: [email protected] 212-813-5900 Submission Plaintiff's Notice of Reliance Filer's Name James D. Weinberger Filer's email [email protected] Signature /s/ James D. Weinberger Date 09/10/2020 Attachments F3676523.PDF(42071 bytes ) F3678658.PDF(2906955 bytes ) F3678659.PDF(5795279 bytes ) F3678660.PDF(4906991 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD ROBERT KIRKMAN, LLC, Cons. Opp. and Canc. Nos. 91217941 (parent), 91217992, 91218267, 91222005, Opposer, 91222719, 91227277, 91233571, 91233806, 91240356, 92068261 and 92068613 -against- PHILLIP THEODOROU and ANNA THEODOROU, Applicants. ROBERT KIRKMAN, LLC, Opposer, -against- STEVEN THEODOROU and PHILLIP THEODOROU, Applicants. OPPOSER’S NOTICE OF RELIANCE ON INTERNET DOCUMENTS Opposer Robert Kirkman, LLC (“Opposer”) hereby makes of record and notifies Applicant- Registrant of its reliance on the following internet documents submitted pursuant to Rule 2.122(e) of the Trademark Rules of Practice, 37 C.F.R. § 2.122(e), TBMP § 704.08(b), and Fed. R. Evid. 401, and authenticated pursuant to Fed. -

Izombie: Six Feet Under and Rising Volume 3 Free Ebook

FREEIZOMBIE: SIX FEET UNDER AND RISING VOLUME 3 EBOOK Mike Allred,Jay Stephens,Chris Roberson | 144 pages | 14 Feb 2012 | DC Comics | 9781401233709 | English | United States iZombie Vol. 3: Six Feet Under & Rising on Apple Books Free shipping. Skip to main content. Email to friends Share on Facebook - opens in a new window or tab Share on Twitter - opens in a new window or tab Share on Pinterest - opens in a new window or tab. Add to Watchlist. People who viewed this item also viewed. Picture Information. Mouse over to Zoom - Click to enlarge. Have one to sell? Sell it yourself. Get the iZombie: Six Feet Under and Rising Volume 3 you ordered or get your money back. Learn more - eBay Money Back Guarantee - opens in new window or tab. Contact seller. Visit store. See other items More See all. Item information Condition:. The item you've selected wasn't added to your cart. Add to Watchlist Unwatch. Watch list is full. No additional import charges at delivery! This item will be posted through the Global Shipping Program and includes international tracking. Learn more - opens in a new window or tab. Doesn't iZombie: Six Feet Under and Rising Volume 3 to Germany See details. Item location:. Posts to:. This amount is subject to change until you make payment. For additional information, see the Global Shipping Program terms and conditions - opens in a new window or tab This amount includes applicable customs duties, taxes, brokerage and other fees. For additional information, see the Global Shipping Program terms and conditions - opens in a new window or tab. -

Normalizing Monstrous Bodies Through Zombie Media

Your Friendly Neighbourhood Zombie: Normalizing Monstrous Bodies Through Zombie Media by Jessica Wind A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016 Jess Wind Abstract Our deepest social fears and anxieties are often communicated through the zombie, but these readings aren’t reflected in contemporary zombie media. Increasingly, we are producing a less scary, less threatening zombie — one that is simply struggling to navigate a society in which it doesn’t fit. I begin to rectify the gap between zombie scholarship and contemporary zombie media by mapping the zombie’s shift from “outbreak narratives” to normalized monsters. If the zombie no longer articulates social fears and anxieties, what purpose does it serve? Through the close examination of these “normalized” zombie media, I read the zombie as possessing a non- normative body whose lived experiences reveal and reflect tensions of identity construction — a process that is muddy, in motion, and never easy. We may be done with the uncontrollable horde, but we’re far from done with the zombie and its connection to us and society. !ii Acknowledgements I would like to start by thanking Sheryl Hamilton for going on this wild zombie-filled journey with me. You guided me as I worked through questions and gained confidence in my project. Without your endless support, thorough feedback, and shared passion for zombies it wouldn’t have been nearly as successful. Thank you for your honesty, deadlines, and coffee. I would also like to thank Irena Knezevic for being so willing and excited to read this many pages about zombies. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Write-In Results Primary 5-23-19 Municpal.Xlsx

Precinct Position WriteIn Votes Party Antrim 1 CLERK OF COURTS Todd Rock 1 Democratic Antrim 1 CORONER Becky Myers 1 Democratic Antrim 1 CORONER Jeff Conner 2 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David Keller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS John Flannery 2 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Forest Myers 1 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Matt Fogal 1 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Matthew Fogal 1 Democratic Antrim 1 JUDGE OF THE SUPERIOR COURT Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 PROTHONOTARY Timothy Sponseller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 REGISTER & RECORDER Linda Miller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SCHOOL DIRECTOR ‐ 2 YR TERM Kristen Sutherin 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SCHOOL DIRECTOR ‐ 4 YR TERM Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SHERIFF Dane Anthony 2 Democratic Antrim 1 SHERIFF Jim Brown 1 Democratic Antrim 1 TOWNSHIP SUPERVISOR ‐ 6 YR TERM Frank Adams 1 Democratic Antrim 2 AUDITOR ‐ 4 YR TERM Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 AUDITOR ‐ 6 YR TERM Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CLERK OF COURTS Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CLERK OF COURTS Todd Rock 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CONTROLLER Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CORONER Jeff Conner 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CORONER Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Bob Thomas 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David S Keller 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David Slye 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS John Flannery 2 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Steve Smith 1 Democratic -

A Feminist Rhetorical Critique of Zombie Apocalypse Television Narrative

Ohio Communication Journal Volume 52 – October 2014, pp. 64-74 The Walking (Gendered) Dead: A Feminist Rhetorical Critique of Zombie Apocalypse Television Narrative John Greene Michaela D.E. Meyer This essay presents a feminist rhetorical criticism of AMC’s The Walking Dead, exposing how hegemonic gender roles reinforce patriarchy within the series. We connect previous research on horror film and television, particularly in the zombie apocalypse genre, to representations of gender roles in popular culture. Our analysis reveals five categories of gendered representation: sexist rhetoric, division of labor, the role of protector, White male leadership, and the role of the dutiful wife. The Walking Dead narrative features women as incapable of surviving the apocalypse without men, renders them slaves to products of consumption (such as clothing), and ultimately strips them of autonomous decision making. We connect these images to the never-ending process of consumption and creation perpetuated by zombie narratives as representative of our social unease with capitalism, consumerism and its link to gendered identity. Over fifty years after George A. Romero forever changed the horror genre with Night of the Living Dead, 5.3 million viewers watched once again as the dead rose to devour the living in the series premiere of AMC’s The Walking Dead (AMC, 2010). The Walking Dead is one of the most-watched pieces of zombie fiction ever created, and is the first that has been successfully launched on cable television. Robert Kirkman, the creator of the graphic novel series on which the show is based, stated that “it’s something that succeeds in movies all the time, but I don’t think anybody has seen survival horror on TV before” (Stelter, 2010). -

An Ultra-Realist Analysis of the Walking Dead As Popular

CMC0010.1177/1741659017721277Crime, Media, CultureRaymen 721277research-article2017 CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Plymouth Electronic Archive and Research Library Article Crime Media Culture 1 –19 Living in the end times through © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: popular culture: An ultra-realist sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659017721277DOI: 10.1177/1741659017721277 analysis of The Walking Dead as journals.sagepub.com/home/cmc popular criminology Thomas Raymen Plymouth University, UK Abstract This article provides an ultra-realist analysis of AMC’s The Walking Dead as a form of ‘popular criminology’. It is argued here that dystopian fiction such as The Walking Dead offers an opportunity for a popular criminology to address what criminologists have described as our discipline’s aetiological crisis in theorizing harmful and violent subjectivities. The social relations, conditions and subjectivities displayed in dystopian fiction are in fact an exacerbation or extrapolation of our present norms, values and subjectivities, rather than a departure from them, and there are numerous real-world criminological parallels depicted within The Walking Dead’s postapocalyptic world. As such, the show possesses a hard kernel of Truth that is of significant utility in progressing criminological theories of violence and harmful subjectivity. The article therefore explores the ideological function of dystopian fiction as the fetishistic disavowal of the dark underbelly of liberal capitalism; and views the show as an example of the ultra-realist concepts of special liberty, the criminal undertaker and the pseudopacification process in action. In drawing on these cutting- edge criminological theories, it is argued that we can use criminological analyses of popular culture to provide incisive insights into the real-world relationship between violence and capitalism, and its proliferation of harmful subjectivities. -

City of Bellingham

A W 55TH LN B C D E F G H I LINGBLOOM RD JORGENSEN PL LAINE RD LAINE CT KENT GIRARD LN DR WHISPER WY BELLINGER RD PLEASANT LN SMITH WY RD STARRY 5400 1 W 54TH LN E 54TH TER 1 CYPRESS WILEY CT DR ST H CT W 53RD VISTA CODYLN PATRIOT LN DR KALA SHIELDS RD PAPETTI LN MEYERS DR WC FIRE CitySTEPHENS DR of Bellingham S LN T N R C DIST #7 5300 E 5300 MURIELDR L IE E N H I STAT #43 E 13TH CRST A MARKET RD T CREST WOOD S R LN MARALEE BEL BEL WESTDR British Columbia, Canada RD NOON KAITLYN CT KAITLYN KAYCEE LN KAYCEE HALLMARKLN NORTHWEST DRNORTHWEST BELLAIRE WY BELLAIRE BELLFERNAV WASCHKE RD MANTHEY RD ALDRICH RD BELLAIRE WY BELLAIRE EVERGRN. DR W SMITH RD E SMITH RD Sumas NORTH N Blaine WC L BYERS LN BELLINGHAM PLANNING & N. B'HAM Y ES DR C 547 LN * PUBLIC ATHLETIC MATHES ON A E PENNY LN G 5200 RAUCH DR C GINGER PL WORKS FIELDS 5200 E N 546 SEAHAWK DR L A STROMERRD ZANDER DR I F Lynden E CREIGHTON RD T D C Maple W IRAL WY Nooksack O M WC R D Birch Falls SPA R A LIBRARY* SPOONBILLLN Custer ADMIN. Bay Kendal KRYS PACIFI TAL POND LN 542 C GINGER PL 5100 5100 PL E 51ST TER Everson INDUST DR U.S. Congressional 548 544 Glacier 2 BYERS RD LARSON RD LARSON RD District #1 E 51ST ST 9 2 SIL 5000 VER 5000 Ferndale Laurel C R CITYLIMITS Deming LABOUNTYDR SUNSET PL PARK County Council District #4 GUIDE MERIDIAN RD SUNSET AVE LANGE RD S T O 539 D R 5 N EGATE WY 542 R K C D I FERNDALE R B WASCHKERD M BEAR CR A I WHITEHORN ST W L 4900 O L 4900 I L L G GRAVELINE RD E E12TH DR HACKETT RD FAT DOGFAT LN 3RDE DR ALDRICH RD KELLY RD Y PATTON RD Pt. -

Do “Prey Species” Hide Their Pain? Implications for Ethical Care and Use of Laboratory Animals

Journal of Applied Animal Ethics Research 2 (2020) 216–236 brill.com/jaae Do “Prey Species” Hide Their Pain? Implications for Ethical Care and Use of Laboratory Animals Larry Carbone Independent scholar; 351 Buena Vista Ave #703E, San Francisco, CA 94117, USA [email protected] Abstract Accurate pain evaluation is essential for ethical review of laboratory animal use. Warnings that “prey species hide their pain,” encourage careful accurate pain assess- ment. In this article, I review relevant literature on prey species’ pain manifestation through the lens of the applied ethics of animal welfare oversight. If dogs are the spe- cies whose pain is most reliably diagnosed, I argue that it is not their diet as predator or prey but rather because dogs and humans can develop trusting relationships and because people invest time and effort in canine pain diagnosis. Pain diagnosis for all animals may improve when humans foster a trusting relationship with animals and invest time into multimodal pain evaluations. Where this is not practical, as with large cohorts of laboratory mice, committees must regard with skepticism assurances that animals “appear” pain-free on experiments, requiring thorough literature searches and sophisticated pain assessments during pilot work. Keywords laboratory animal ‒ pain ‒ animal welfare ‒ ethics ‒ animal behavior 1 Introduction As a veterinarian with an interest in laboratory animal pain management, I have read articles and reviewed manuscripts on how to diagnose a mouse in pain. The challenge, some authors warn, is that mice and other “prey species” © LARRY CARBONE, 2020 | doi:10.1163/25889567-bja10001 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. -

Media Website Contact List

MEDIA WEBSITE CONTACT LIST version: 8/2016 Outlet Name First Name Last Name Title Email Address Website Address Bleeding Cool Richard Johnston Editor-in-Chief [email protected] http://www.bleedingcool.com/ Comics Alliance Andrew Wheeler Editor in Chief [email protected] http://comicsalliance.com/ Comics Alliance Kevin Gaussoin Editor in Chief [email protected] http://comicsalliance.com/ Comic Book Resources Albert Ching Managing Editor [email protected] http://www.comicbookresources.com/ Comic Vine Tony Guerrero Editor-in-Chief [email protected] http://www.comicbookresources.com/ ComicBook.com James Viscardi Editor in Chief [email protected] http://comicbook.com/ Forces of Geek Erin Maxwell Reporter [email protected] http://www.forcesofgeek.com/ IGN Entertainment Joshua Yehl Comics Editor [email protected] http://www.ign.com/ ICV2 Milton Griepp Editor in Chief [email protected] http://icv2.com/ Newsarama Chris Arrant Editor-in-Chief [email protected] http://www.newsarama.com/ The Beat Heidi MacDonald Editor in Chief [email protected] http://www.comicsbeat.com/ Comicosity Matt Santori-Griffith Senior Editor [email protected] http://www.comicosity.com/ The Mary Sue Maddy Myers Editor [email protected] http://www.themarysue.com/ The Mary Sue Dan Van Winkle Editor [email protected] http://www.themarysue.com/ Multiversity Comics Brian Salvatore Editor-in-Chief [email protected] http://multiversitycomics.com/ Comic Crusaders [email protected] www.comiccrusaders.com/ Graphic Policy Brett Schenker Founder / Blogger in Chief [email protected] https://graphicpolicy.com/ THIS LIST OF CONTACTS IS DESIGNED TO BE A RESOURCE FOR PUBLISHERS TO HELP PROMOTE THEIR PROJECTS TO THE PUBLIC.