The Metanarrative Paradigm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty's Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism

Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center Occasional Papers Series Series Editor Tony Saich Deputy Editor Jessica Engelman The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing powerful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. The Ford Foundation is a founding donor of the Center. Additional information about the Ash Center is available at ash.harvard.edu. This research paper is one in a series funded by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. The views expressed in the Ash Center Occasional Papers Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series are intended to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. This paper is copyrighted by the author(s). It cannot be reproduced or reused without permission. Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Letter from the Editor The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. -

MOVEMENT BUILDING THROUGH METANARRATIVE an Integral Ideological Response to Climate Change Jordan Luftig

MOVEMENT BUILDING THROUGH METANARRATIVE An Integral Ideological Response to Climate Change Jordan Luftig ABSTRACT The State of the World Forum has chosen the AQAL model as its framework and oper- ang system for its 10-year plan to address climate change. This arcle proposes that tackling cli- mate change head-on is imperave yet insufficient, and the Forum’s 2020 vision to green the world economy should be framed in terms of a global integral movement. I use the conceptual lens of ideology as a heurisc device to explore the AQAL model and mine it for ideas that can be converted into levers to grow the integral movement and contribute to the transformaon of society. I present narrave as an essenal lever for movement building and explore it in depth through consideraon of Ken Wilber’s “beyond flatland” metanarrave and the public narrave approach used by Barack Obama’s campaign for President of the United States. KEY WORDS: climate change; ideology; metanarrave; public narrave; social movements In the face of a heating planet, in the midst of collapsing economic systems, in the face of an approaching catastrophe ‘far outside human experience,’ we need more than rhetoric. We need a plan. We need a campaign that brings people together—that mobilizes action in ways that make common sense and offer all sectors of society a common good. We need a vision that provides a more viable basis for society’s rela- tionship with the Earth. The extremity of our crisis makes it paradoxically possible to create a new world. – State of the World Forum1 plan? A campaign that unites people and mobilizes action? A vision for creating a new world? In the A modern age, this has been the stuff of political ideologies. -

Exploring the Hip-Hop Culture Experience in a British Online Community

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2010 Virtual Hood: Exploring The Hip-hop Culture Experience In A British Online Community. Natalia Cherjovsky University of Central Florida Part of the Sociology of Culture Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Cherjovsky, Natalia, "Virtual Hood: Exploring The Hip-hop Culture Experience In A British Online Community." (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4199. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4199 VIRTUAL HOOD: EXPLORING THE HIP-HOP CULTURE EXPERIENCE IN A BRITISH ONLINE COMMUNITY by NATALIA CHERJOVSKY B.S. Hunter College, 1999 M.A. Rollins College, 2003 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2010 Major Professor: Anthony Grajeda © 2010 Natalia Cherjovsky ii ABSTRACT In this fast-paced, globalized world, certain online sites represent a hybrid personal- public sphere–where like-minded people commune regardless of physical distance, time difference, or lack of synchronicity. Sites that feature chat rooms and forums can offer a deep- rooted sense of community and facilitate the forging of relationships and cultivation of ideologies. -

WAV / Kotori Magazine Issue 6 the Prodigy Dilated Peoples George

WWW.KOTORIMAG.COM MAGAZINE WWW.KOTORIMAG.COM MAGAZINE TM MUSIC/ART/POLITICS/CULTURE MUSIC/ART/POLITICS/CULTURE 006 / THE PRODIGY DILATED PEOPLES - GEORGE CLINTON FLIGHT COMICS - METRIC - SASHA & DIGWEED GRAM RABBIT MALKOVICH MUSIC DJ MUGGS PORTUGAL. THE MAN GOAPELE TIM FITE TWO GALLANTS USA $3.99 CANADA $4.99 ISSUE 6 SILVERSUN PICKUPS 0 6 0 74470 04910 4 BOMBAY DUB ORCHESTRA KOTORIMAG.COM RSE7!6SPRINGADPDF0- # - 9 #- -9 #9 #-9 + TABLE OF CONTENTS DILATED PEOPLES 12 They’re almost prophetic, hooking up with Kanye and Alchemist before most of the world even knew those names...now they’re back, and with 20/20, their vision is better than ever. Baby, Rakaa, and Evidence get all loose with our one and only Simonita. THE PRODIGY 40 Let the madness ensue as Maxim, Keith, and Liam reload The Prodigy cannon for another go round. Safety and sanity be damned. The electronic music world has never been the same since the Firestarter grabbed hold of us in the 90s. In this issue we explore the trials and tribs of megastardom and the never ending struggle to retain the punk rock performance belt they’ve been brandishing for years. GEORGE CLINTON 48 “Think! It ain’t illegal yet!!” That’s about the only venture outside the halls of justice that the P Funk Master has been able to afford of WOLFMOTHER late. Four score and seven lawyers later, the 08 man who fostered the groove for a nation of hip “You ever heard of Wolfmother?” ‘No.’ hop protagonists gets his pay day and let’s his “WOLFMOTHER WOLFMOTHER WOLF- story be told here in this exclusive interview. -

Patterson Hood Looks Back to Move Forward on His New Best Release, Murdering Oscar (And Other Love Songs)

ONE YEAR ISSUE! FREE! METRIC • ASHER ROTH • CYCLE OF PAIN THE GINGER ENVELOPE • ST. VINCENT • CAGE THE ELEPHANT • MATTHEW SWEET CARS CAN BE BLUE • EELS • AND MORE! FOR FANS OF MUSIC & THOSE WHO MAKE IT ISSUE 8 TEN QUESTIONS WITH...311 THE UNDYING ROCK Father OPERA GIRLS IN ATHENS ROCK... Knows LITERALLY NIC CAGE: A STAR’S Best: TREK Patterson Hood PLUS! ULTIMATE Looks Back to MUSICIAN’S Move Forward GEAR GUIDE ATHFEST TURNS 13: OUR 2009 GUIDE 13th annual 4 days of music, art, camping & loving le: Profi SWOP 13th annual No overlapping sets, 35 Headlining Bands, 40+ Hours of music, All Ages, rain or Shine, Even Better VIP section, Microbrews, Kids area, Family camping, Drum circles, Food & Craft vendors & much much more! Ad Name: Full Flavor Closing Date: 1.7.9 Trim: 8.25 x 10.75 Item #: PSE20089386 QC: RR Bleed: 8.75 x 11.25 Job/Order #:594830-199138 Pub: Athens Blur Live: 7.5 x 10 cover story Father Knows (14) Athens legend and Drive By-Truck- ers frontman Patterson Hood looks back to move forward on his new Best release, Murdering Oscar (And Other Love Songs). —Alec Wooden (41) (45) After 19 years, 311 continues Athens’ homegrown music to uplift spirits with reggae- and arts festival continues infused rock on the first to get stronger with each album in nearly four years. passing year. tenquestions with311 — Nicole Black No — Alec Wooden Mystery About it: (51) (45) Ten bands beat the new singles craze and prove the concept album is back on the rise. turns — Natalie B. -

Issue 139.Pmd

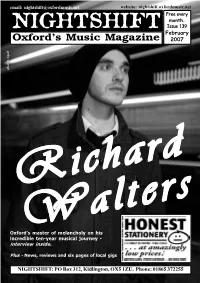

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 139 February Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 photo by Squib RichardRichardRichard Oxford’sWaltersWaltersWalters master of melancholy on his incredible ten-year musical journey - interview inside. Plus - News, reviews and six pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS photo: Matt Sage Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] BANDS AND SINGERS wanting to play this most significant releases as well as the best of year’s Oxford Punt on May 9th have until the its current roster. The label began as a monthly 15th March to send CDs in. The Punt, now in singles club back in 1997 with Dustball’s ‘Senor its tenth year, will feature nineteen acts across Nachos’, and was responsible for The Young six venues in the city centre over the course of Knives’ debut single and mini-album as well as one night. The Punt is widely recognised as the debut releases by Unbelievable Truth and REM were surprise guests of Robyn premier showcase of new local talent, having, in Nought. The box set features tracks by Hitchcock at the Zodiac last month. Michael the past, provided early gigs for The Young Unbelievable Truth, Nought, Beaker and The Stipe and Mike Mills joined bandmate Pete Knives, Fell City Girl and Goldrush amongst Evenings as well as non-Oxford acts such as Buck - part of Hitchcock’s regular touring others. Venues taking part this year are Borders, Beulah, Elf Power and new signings My band, The Venus 3 - onstage for the encores, QI Club, the Wheatsheaf, the Music Market, Device. -

Ifpi.Org Recording Industry in Numbers 2009 the Definitive Source of Global Music Market Information

Recording Industry In Numbers 2009 The Definitive Source Of Global Music Market Information www.ifpi.org Recording Industry In Numbers 2009 The Definitive Source Of Global Music Market Information www.ifpi.org It all started in a café in Bristol, England in 1934, when dance musicians were replaced by vinyl records played on a phonograph. Back then, PPL had just two FOR 75 YEARS, members – EMI and Decca. Now we have over 3,400 record companies and, following a merger with the principal performer societies, 39,500 performers. In addition, our reach has extended to include international repertoire and overseas PPL HAS BEEN royalties through 42 bilateral agreements with similar organisations around the world. PPL licenses businesses playing music, from broadcasters to nightclubs, from GROWING INTO A streaming services to sports studios, from internet radio to community radio. Licensees are able to obtain a single licence for the entire PPL repertoire, a service which is seen as increasingly valuable for both rightholders and users alike as MODERN SERVICE consumption of music continues to grow. Broadcasters such as the BBC have commented that they simply would not be able to use music at such a scale, across nine TV channels, sixty radio stations, the iPlayer and numerous online services ORGANISATION without a licence from PPL. The PPL licence is equally valuable to other users, such as commercial radio stations, BT Vision, Virgin Media, Last.fm and even the fourteen oil rigs that want to keep their oil workers entertained on their tours of duty. FOR THE MUSIC For the performers and record companies who entrust their rights to PPL, the income from these new distribution outlets is becoming increasingly valuable. -

Discourses We Live By

Discourses We Live By Narratives of Educational and Social Endeavour W RIGHT EDITED BY HAZEL R. WRIGHT AND MARIANNE HØYEN Discourses We Live By AND What are the infl uences that govern how people view their worlds? What are the embedded Narratives of Educational values and prac� ces that underpin the ways people think and act? H ØYEN and Social Endeavour Discourses We Live By approaches these ques� ons through narra� ve research, in a process that uses words, images, ac� vi� es or artefacts to ask people – either individually or collec� vely within social groupings – to examine, discuss, portray or otherwise make public their place in the world, their sense of belonging to (and iden� ty within) the physical and cultural space they inhabit. DITED BY AZEL RIGHT E H R. W This book is a rich and mul� faceted collec� on of twenty-eight chapters that use varied lenses to examine the discourses that shape people’s lives. The contributors are themselves from many AND MARIANNE HØYEN backgrounds – diff erent academic disciplines within the humani� es and social sciences, diverse professional prac� ces and a range of countries and cultures. They represent a broad spectrum of age, status and outlook, and variously apply their research methods – but share a common interest in people, their lives, thoughts and ac� ons. Gathering such eclec� c experiences as those of student-teachers in Kenya, a released prisoner in Denmark, academics in Colombia, a group of migrants learning English, and gambling addic� on support-workers in Italy, alongside D more mainstream educa� onal themes, the book presents a fascina� ng array of insights. -

Christ on the Postmodern Stage: Debunking Christian Metanarrative Through Contemporary Passion Plays

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2016 Christ on the Postmodern Stage: Debunking Christian Metanarrative Through Contemporary Passion Plays Joseph Dambrosi University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Dambrosi, Joseph, "Christ on the Postmodern Stage: Debunking Christian Metanarrative Through Contemporary Passion Plays" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4986. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4986 CHRIST ON THE POSTMODERN STAGE: DEBUNKING CHRISTIAN METANARRATIVE THROUGH CONTEMPORARY PASSION PLAYS by JOSEPH R. D’AMBROSI B.A. Messiah College, 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2016 Major Professor: Julia Listengarten © 2016 Joseph R. D’Ambrosi ii ABSTRACT As a Christian theatre artist with a conservative upbringing, I continually seek to discover the role of postmodernism in faith and how this intersection correlates with theatre in a postmodern society. In a profession that constantly challenges the status quo of Christian living, and a faith that frowns upon most “secular” behavior, I find myself in a position of questioning the connection between these two components of my life. -

Press Layout

2 Vol. XXX, Issue 12 | Tuesday, April 14, 2009 news Oh, the Humanity! lected 421 signatures in total, 30 of Wil - elected president, the consequence is said. By Natalie Crnosija son’s signators had put their SOLAR ID that the executive vice president will be - Senator Aharon Eliezer Benelyahoo numbers in the place of NetID num - come the president for the entire fol - joined in the criticism, saying that a bers. Though the USG election bylaws lowing year.” dangerous electoral appeals precedent The Undergraduate Student Gov - do require SOLAR ID numbers for can - The terms of vacancy would require could be established by accepting Wil - ernment’s Supreme Court unanimously didacy petitions, the petition forms re - governmental reshuffling in late Octo - son’s candidacy. ruled on March 30 that this year’s only quire NetIDs. Patestas, who followed ber, a task which the current Senate was Benelyahoo and Senator Syed Haq presidential candidate was permitted to the election bylaws’ NetID requirement, not eager to support. both pointed out that Wilson’s fate did campaign, and essentially win the USG disqualified Wilson on that basis. The Brady, who would later act as Wil - not fall under the Senate’s jurisdiction. presidency, after his candidacy was ini - reason for the invalidation of the son’s advocate during the March 30 This, however, did not halt the debate. tially disqualified by the USG Constitu - SOLAR ID number requirement exists hearing, expressed his dissatisfaction “We can make corrections to the tion’s incongruous election bylaws. because that number could be used to with the bylaws but said the situation bylaws,” Haq said. -

Canon and Grand Narrative in the Philosophy of History

CANON AND GRAND NARRATIVE IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY J. Randall Groves Abstract: Three recent thinkers, Arthur Danto, David Gress and Ricardo Duchesne, have proposed philosophies of cultural history that emphasize the importance of narrative, canon and Grand Narrative. An examination of their views will suggest that contrary to the postmodernist announcement of its death, Grand Narrative is very much alive. In this paper I propose a conception of Grand Narrative that accepts key postmodern criticisms but can still function in the ways Metanarratives traditionally function. The result is a defensible conception of Grand Narrative that is limited in its claims and purpose yet provides the organizing structure that traditional Grand Narratives have provided. Introduction In 1984 Francois Lyotard published his famous postmodernist manifesto, The Postmodern Condition. In that work he announced the end of the Grand Narrative, and since that time the postmodernist position is one that while it may not be dominant, is certainly widely held. While it is true that there is widespread skepticism that any particular Grand Narrative can function in the traditional fashion, providing an unequivocal foundation for a way of living, this has not stopped scholars from producing and defending Grand Narratives. Three individuals, David Gress, Arthur Danto and Ricardo Duchesne, go against the prevailing trend away from Grand Narrative. All three thinkers address the use of narrative, interpretive analysis and canonicity. If the canon of great works and the ideas in them have had significant effects on world history, then these works and ideas merit special consideration in education. The canon of great works is becoming ever more neglected in education, so this paper can be read as an attempt to push back against this trend. -

Re-Placing Rural Education: AERA Special Interest Group on Rural Education Career Achievement Award Lecture

Journal of Research in Rural Education, 2021, 37(3) Re-Placing Rural Education: AERA Special Interest Group on Rural Education Career Achievement Award Lecture Michael Corbett Acadia University Citation: Corbett, M. (2021). Re-placing rural education: AERA special interest group on rural education career achievement award lecture. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 37(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.26209/jrre3703 All reification is a forgetting. – Horkheimer & Adorno (1947/1994) Introduction: An Ambivalent Preoccupation with Place see as the emerging field of rural education, influenced by developments in sociology, geography, political science, I would like to begin by acknowledging that the place and area studies. Following the excellent critical lead from which I speak is Mi’kma’ki, the traditional and of Craig and Aimee Howley (2018), in preparing this unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq people. This people will piece, I have been thinking about the development of the enter this story in due course. The colonial name for this field in terms of its assumed core pragmatist and idealist place today is Nova Scotia, Canada, which evolved out of sociogeographic theorizations, which I think remain mired the original colonial place names this territory shares with in 19th- and early 20th-century ideascapes that are no longer the United States such as Acadie, British North America, and up for the task of helping us appropriately understand the New France (Corbett, 2013, 2021a). These names represent current moment. An important component of this lingering the changing colonial hegemonies of which the Canadian modernist discourse is a vision of spatial transformation that state with its ten provinces and three territories is the latest juxtaposed ascendent urbanism and a parallel rural decline, incarnation.