Birmingham-Aston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read the Games Transport Plan

GAMES TRANSPORT PLAN 1 Foreword 3 Introduction 4 Purpose of Document 6 Policy and Strategy Background 7 The Games Birmingham 2022 10 The Transport Strategy 14 Transport during the Games 20 Games Family Transportation 51 Creating a Transport Legacy for All 60 Consultation and Engagement 62 Appendix A 64 Appendix B 65 2 1. FOREWORD The West Midlands is the largest urban area outside With the eyes of the world on Birmingham, our key priority will be to Greater London with a population of over 4 million ensure that the region is always kept moving and that every athlete and spectator arrives at their event in plenty of time. Our aim is people. The region has a rich history and a diverse that the Games are fully inclusive, accessible and as sustainable as economy with specialisms in creative industries, possible. We are investing in measures to get as many people walking, cycling or using public transport as their preferred and available finance and manufacturing. means of transport, both to the event and in the longer term as a In recent years, the West Midlands has been going through a positive legacy from these Games. This includes rebuilding confidence renaissance, with significant investment in housing, transport and in sustainable travel and encouraging as many people as possible to jobs. The region has real ambition to play its part on the world stage to take active travel forms of transport (such as walking and cycling) to tackle climate change and has already set challenging targets. increase their levels of physical activity and wellbeing as we emerge from Covid-19 restrictions. -

145 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

145 bus time schedule & line map 145 Rubery - Longbridge - Bromsgrove - Droitwich View In Website Mode The 145 bus line (Rubery - Longbridge - Bromsgrove - Droitwich) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bromsgrove: 5:26 PM (2) Bromsgrove: 8:00 AM (3) Droitwich Spa: 7:22 AM - 4:56 PM (4) Longbridge: 6:45 AM - 6:10 PM (5) Rubery: 9:13 AM - 12:50 PM (6) Wychbold: 6:16 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 145 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 145 bus arriving. -

Professor Christopher Julian Hewitt Freng 1969–2019

Biotechnol Lett https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-019-02717-y (0123456789().,-volV)( 0123456789().,-volV) OBITUARY Professor Christopher Julian Hewitt FREng 1969–2019 Ó Springer Nature B.V. 2019 It is with deep sadness that we announce the death of as microbial fermentation, bio-remediation, bio-trans- Professor Chris Hewitt FREng, an Executive Editor of formation, brewing and cell culture. He was also the Biotechnology Letters since 2007 and Editor in Chief co-founder of the Centre for Biological Engineering at since last year, who died in the early hours of 25th July Loughborough University, where he developed a 2019, at the age of 50. He had suffered a short illness world-leading team in regenerative medicine biopro- but his passing was very unexpected. cessing. In particular, his team made a significant Chris graduated with a first class honours degree in contribution to the literature on the culture and Microbiology from Royal Holloway College, Univer- recovery of fully functional human mesenchymal sity of London in 1990 and then went to the University stem cells in stirred bioreactors based on sound of Birmingham to read for a Ph.D. in Biochemical biochemical engineering and fluid dynamic consider- Engineering in the School of Chemical Engineering ations essential to scale-up for commercialisation. (1993). After a short break, mainly in industry, he In recognition of his achievements, he was awarded a returned to the School in 1996 as a post-doc at the end DSc in Biochemical Engineering from Loughborough of which in 1999 he was appointed Lecturer, then University (2013) and the Donald Medal by the Institu- Senior Lecturer in Biochemical Engineering. -

Aston Business School Aston University Aston Triangle Birmingham B4 7ET United Kingdom Website Erasmus Institution Code UK BIRMING 01

Information for Partner Institutions Incoming Postgraduate Exchange Students 2019- 2020 Address Aston Business School Aston University Aston Triangle Birmingham B4 7ET United Kingdom Website www.abs.aston.ac.uk Erasmus Institution Code UK BIRMING 01 KEY CONTACTS: Saskia Hansen Institutional Erasmus Coordinator Pro-Vice Chancellor International Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 4664 Email: [email protected] Aston Business School Professor George Feiger Executive Dean Email Rebecca Okey Email: [email protected] Associate Dean Dr Geoff Parkes International Email: [email protected] International Relations Selena Teeling Manager Email: [email protected] Incoming and Outgoing International and Student Exchange Students Development Office Tel: ++44 (0) 121 204 3279 Email: [email protected] Postgraduate Student Elsa Zenatti-Daniels Development Lead Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 3279 Email: [email protected] International and Student Ellie Crean Development Coordinator Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 3255 Email: [email protected] Contents Academic Information Important Dates 2 Entry Requirements 4 Application Procedures: 1 or 2 Term Exchange 5 Application Procedures: Double Degree Students 7 Credits and Course Layout 8 Study Methods and Grading System 9 MSc Module Selection: 1 or 2 Term Exchange 10 Course Selection: Double Degrees 11 The Aston Edge (MSc Double Degree) 12 Induction and Erasmus Form Details 13 Conditions for Eligibility 14 Practical Information Visas and Health Insurance 16 Accommodation 17 Support Facilities 20 Student Life at Aston 21 Employments and Careers Services 22 Health and Well Being at Aston 23 Academic Information Important Dates APPLICATION DEADLINES The nomination deadline for the fall term will be 1 June 2019 and the application deadline will be 20 June 2019 for double degree and Term 1 exchange students. -

Birmingham a Powerful City of Spirit

Curriculum Vitae Birmingham A powerful city of spirit Bio Timeline of Experience Property investment – As the second largest city in the UK, I have a lot to offer. I have great Birmingham, UK connections thanks to being so centrally located, as over 90% of the UK market is only a four hour drive away. The proposed HS2 railway is poised I’ve made a range to improve this further – residents will be able to commute to London in of investments over less than an hour. I thrive in fast-paced environments, as well as calmer the years. The overall waters – my vast canal route covers more miles than the waterways average house price is of Venice. £199,781, up 6% up 2018 - 2019 - 2019 2018 on the previous year. Truly a national treasure, my famed Jewellery Quarter contains over 800 businesses specialising in handcrafted or vintage jewellery and produces 40% of the UK’s jewellery. Edgbaston is home to the famed cricket ground Job application surge – and sees regular county matches, alongside the England cricket team for Birmingham, UK international or test matches. My creative and digital district, the Custard I’ve continued to refine Factory, is buzzing with artists, innovators, developers, retailers, chefs and my Sales and Customer connoisseurs of music. Other key trades include manufacturing (largely Service skills, seeing a cars, motorcycles and bicycles), alongside engineering and services. rise in job applications of 34% and 29% between May 2018 2018 - 2019 2018 Education Skills and January 2019. 4 I have an international Launch of Birmingham Festivals – universities including the perspective, with Brummies Birmingham, UK University of Birmingham, Aston, hailing from around the world Newman and Birmingham City. -

Economic-Impact-Of-University-Of-Birmingham-Full-Report.Pdf

The impact of the University of Birmingham April 2013 The impact of the University of Birmingham A report for the University of Birmingham April 2013 The impact of the University of Birmingham April 2013 Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................... 3 1 Introduction ..................................................................................... 7 2 The University as an educator ........................................................ 9 3 The University as an employer ..................................................... 19 4 The economic impact of the University ....................................... 22 5 The University as a research hub ................................................. 43 6 The University as an international gateway ................................. 48 7 The University as a neighbour ...................................................... 56 Bibliography ................................................................................................ 67 2 The impact of the University of Birmingham April 2013 Executive Summary The University as an educator... The University of Birmingham draws students from all over the UK and the rest of the world to study at its Edgbaston campus. In 2011/12, its 27,800 students represented over 150 nationalities . The attraction of the University led over 20,700 students to move to or remain in Birmingham to study. At a regional level, it is estimated that the University attracted 22,400 people to either move to, -

West Midlands Schools

List of West Midlands Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbot Beyne School Staffordshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Alcester Academy Warwickshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Alcester Grammar School Warwickshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Aldersley High School Wolverhampton 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Aldridge -

3 the Fairways Litle Aston

3 The Fairways, Little Aston, B74 3UG Parker Hall Set in an exclusive gated development in the ● Executive Detached Residence ● Third En Suite & Family Bathroom The composite front door opens into Reception desirable Little Aston is The Fairways, a ● Highly Desirable Location on Exclusive ● Bedrooms with TV Power Supply & Aerial Hall having porcelain tiled flooring, oak and glass contemporary detached residence offering Secure Gated Development ● Peaceful Position on Private Lane staircase rising to the first floor with a window to executive accommodation, six double ● Outstanding Specification throughout ● Double Garage & Parking the side, understairs storage and under floor heating bedrooms and an idyllic location on this ● Two Spacious Reception Rooms ● South Facing Gardens which extends throughout the ground floor private road. Built in 2014 by the renowned ● Open Plan Dining & Living Kitchen ● Peaceful Location on Private Lane accommodation. Doors open into: luxury homebuilder Spitfire Homes, this ● Reception Hall, Utility & Cloakroom ● Well Placed for Amenities, Commuter beautifully presented property enjoys a wealth Dining Room 4.24 x 3.22m (approx 13‘10 x 10‘6) ● Six Superb Double Bedrooms Routes & Schools of accommodation finished to the highest Having a bay window to the front aspect and black ● Master with En Suite & Dressing Room ● 4 Years NHBC Warranty Retained specification including a Poggenpohl kitchen, American walnut flooring matching the property’s ● Villeroy & Boch bathrooms, black American Bedroom Two Dressing Room & En Suite internal doors walnut doors, brushed aluminium sockets and switches an oak and glass staircase, with contemporary finishes including under floor heating to the ground floor, 5 amp sockets and Cat 6 cabling . -

Birmingham Commonwealth Games 2022: Cultural Programme

Birmingham Commonwealth Games 2022: Cultural Programme Chair Alan Heap Purple Monster Christina Boxer Warwick District Council Tim Hodgson & Louisa Davies Senior Producers (Cultural Programme & Live Sites) for Birmingham 2022. Christina Boxer Warwick District Council BOWLS & PARA BOWLS Warwick District VENUE 2022 Commonwealth Games Project ENHANCED Introduction ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICAL ACTIVITY & WELLBEING Spark Symposium 14.02.2020 MAXIMISING OPPORTUNITIES TO SHOWCASE LOCAL ENTERPRISE, CULTURE, TOURISM www.warwickdc.gov.uk & EVENTS Venues – A Regional Showcase Birmingham2022www.warwickdc.gov.uk presentation | slide26/01/2018 Lawn Bowls & Para Bowls o Matches on 9 days of competition o Minimum 2 sessions a day o 5,000 – 6,000 visitors to the District daily - Spectators - Competitors - Officials - Volunteers - Media o 240 lawn bowls competitors (2018) o Integrated Para Bowls o 28 nations (2018) www.warwickdc.gov.uk | 26/01/2018Jan 2020 WDC Commonwealth Games Project Objectives Successful CG2022 Bowls & Para Bowls Improved Bowls Venue Competition Participation & Diversity Enhanced Wider Victoria Park Facilities, Access & Riverside Links Raised Awareness of the Wellbeing Benefits of an Active Lifestyle Maximised Opportunities for Local Enterprise, Culture, Tourism and Showcasing WDC’s Reputation for Events Delivery www.warwickdc.gov.ukApril | 26/01/2018 2017 – March 2023 Louisa Davies Tim Hodgson Senior Producers, Cultural Programme & Live Sites - BIRMINGHAM 2022 BIRMINGHAM 2022 CULTURAL PROGRAMME Introduction Spark 14 February 2020 INTRODUCTION -

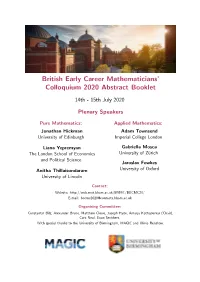

British Early Career Mathematicians' Colloquium 2020 Abstract Booklet

British Early Career Mathematicians' Colloquium 2020 Abstract Booklet 14th - 15th July 2020 Plenary Speakers Pure Mathematics: Applied Mathematics: Jonathan Hickman Adam Townsend University of Edinburgh Imperial College London Liana Yepremyan Gabriella Mosca The London School of Economics University of Z¨urich and Political Science Jaroslav Fowkes Anitha Thillaisundaram University of Oxford University of Lincoln Contact: Website: http://web.mat.bham.ac.uk/BYMC/BECMC20/ E-mail: [email protected] Organising Committee: Constantin Bilz, Alexander Brune, Matthew Clowe, Joseph Hyde, Amarja Kathapurkar (Chair), Cara Neal, Euan Smithers. With special thanks to the University of Birmingham, MAGIC and Olivia Renshaw. Tuesday 14th July 2020 9.30-9.50 Welcome session On convergence of Fourier integrals Microscale to macroscale in suspension mechanics 10.00-10.50 Jonathan Hickman (Plenary Speaker) Adam Townsend (Plenary Speaker) 10.55-11.30 Group networking session Strong components of random digraphs from the The evolution of a three dimensional microbubble in non- Blocks of finite groups of tame type 11.35-12.00 configuration model: the barely subcritical regime Newtonian fluid Norman MacGregor Matthew Coulson Eoin O'Brien Large trees in tournaments Donovan's conjecture and the classification of blocks Order from disorder: chaos, turbulence and recurrent flow 12.10-12.35 Alistair Benford Cesare Giulio Ardito Edward Redfern Lunch break MorphoMecanX: mixing (plant) biology with physics, Ryser's conjecture and more 14.00-14.50 mathematics -

Your Passport to University in the Uk

YOUR PASSPORT TO UNIVERSITY IN THE UK kaplanpathways.partners/aston YOU’LL ENJOY: YOUR ROUTE TO A • Complete preparation for your degree • Guaranteed entry to LIFE-CHANGING DEGREE Aston University* If you don’t quite qualify for a degree at Aston University, you can still gain • Access to university facilities in London entry with a pathway course at Kaplan International College (KIC) London. • Dedicated support services It’s your very own passport to university. • High-quality accommodation FOR STUDENTS WHO HAVE COMPLETED HIGH SCHOOL WITH GOOD GRADES PROGRESS TO 1 OF 30+ DEGREES AT ASTON Graduate International Bachelor’s Bachelor’s Subject areas include: Year One degree year 2 degree year 3 with a degree from Aston • Accounting at KIC London at university at university University • Business Analytics • Design Engineering • Electronic Engineering FOR STUDENTS WITH A BACHELOR’S DEGREE OR EQUIVALENT • Finance • Human Resources • Investment Analysis Master’s Graduate • Management Pre-Master’s degree with a degree • Marketing at KIC London 1 year at from Aston • Mechanical Engineering university University • Strategic Marketing • Supply Chain Management + many more * When you pass your KIC London pathway course at the required level and with good attendance WHY STUDY AT ASTON UNIVERSITY? Top 20 in the UK for student experienceT1 2nd in the UK for teaching effectivenessT2 Globally elite Business School, with triple accreditation Top 20 in the UK for graduate prospectsC Excellent location in Birmingham city centre Business Top 20 in the UKT1 MASUD FROM BANGLADESH MASTER’S IN HUMAN Marketing RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND BUSINESS 12th in the UKC “Aston University is an excellent place to study, with great resources. -

The Aston Mba

THE ASTON MBA GET THE EDGE TO SUCCEED ASTONMBA.COM TRIPLE ACCREDITED 02 The Aston MBA Aston Business School 03 CONTENTS 04 Creating tomorrow’s leaders today 06 Birmingham and Aston life 08 The Aston Edge 10 Getting The Edge 12 With you all the way: induction and learning approach 14 With you all the way: career and alumni support 16 Designed for success 18 MBA core modules 20 Real world results 22 Study routes - Full-time 24 Study routes - Online 26 Study routes - Executive Part-time 28 Entry requirements and admissions information 30 How to apply 04 Aston Business School The Aston MBA CREATING TOMORROW’S LEADERS TODAY The Aston MBA is an intensive programme designed for professionals who have already made their mark in business and are ready to take their careers to the next level. It draws on our world-leading Triple accredited The most rewarding MBA business research and our global We are in the top one per cent of Our full-time MBA was ranked 1st network of corporate connections business schools worldwide with in the UK and 2nd in the world to transform you into a dynamic triple accreditation from AMBA, for return on investment by The and agile business leader. AACSB and EQUIS, the leading Economist (Good-value MBAs 2014). accreditation bodies for business Our programme enables you schools in the UK, USA and Europe. to gain a critical perspective on Globally recognised your own management style and For more than 60 years we have World leading the insight to move your career conducted pioneering research forward, giving you new skills, 100 per cent of our business into contemporary business opportunities and connections.