This Item Was Submitted to Loughborough's Institutional Repository by the Author and Is Made Available Under the Following

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Professor Christopher Julian Hewitt Freng 1969–2019

Biotechnol Lett https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-019-02717-y (0123456789().,-volV)( 0123456789().,-volV) OBITUARY Professor Christopher Julian Hewitt FREng 1969–2019 Ó Springer Nature B.V. 2019 It is with deep sadness that we announce the death of as microbial fermentation, bio-remediation, bio-trans- Professor Chris Hewitt FREng, an Executive Editor of formation, brewing and cell culture. He was also the Biotechnology Letters since 2007 and Editor in Chief co-founder of the Centre for Biological Engineering at since last year, who died in the early hours of 25th July Loughborough University, where he developed a 2019, at the age of 50. He had suffered a short illness world-leading team in regenerative medicine biopro- but his passing was very unexpected. cessing. In particular, his team made a significant Chris graduated with a first class honours degree in contribution to the literature on the culture and Microbiology from Royal Holloway College, Univer- recovery of fully functional human mesenchymal sity of London in 1990 and then went to the University stem cells in stirred bioreactors based on sound of Birmingham to read for a Ph.D. in Biochemical biochemical engineering and fluid dynamic consider- Engineering in the School of Chemical Engineering ations essential to scale-up for commercialisation. (1993). After a short break, mainly in industry, he In recognition of his achievements, he was awarded a returned to the School in 1996 as a post-doc at the end DSc in Biochemical Engineering from Loughborough of which in 1999 he was appointed Lecturer, then University (2013) and the Donald Medal by the Institu- Senior Lecturer in Biochemical Engineering. -

Aston Business School Aston University Aston Triangle Birmingham B4 7ET United Kingdom Website Erasmus Institution Code UK BIRMING 01

Information for Partner Institutions Incoming Postgraduate Exchange Students 2019- 2020 Address Aston Business School Aston University Aston Triangle Birmingham B4 7ET United Kingdom Website www.abs.aston.ac.uk Erasmus Institution Code UK BIRMING 01 KEY CONTACTS: Saskia Hansen Institutional Erasmus Coordinator Pro-Vice Chancellor International Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 4664 Email: [email protected] Aston Business School Professor George Feiger Executive Dean Email Rebecca Okey Email: [email protected] Associate Dean Dr Geoff Parkes International Email: [email protected] International Relations Selena Teeling Manager Email: [email protected] Incoming and Outgoing International and Student Exchange Students Development Office Tel: ++44 (0) 121 204 3279 Email: [email protected] Postgraduate Student Elsa Zenatti-Daniels Development Lead Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 3279 Email: [email protected] International and Student Ellie Crean Development Coordinator Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 3255 Email: [email protected] Contents Academic Information Important Dates 2 Entry Requirements 4 Application Procedures: 1 or 2 Term Exchange 5 Application Procedures: Double Degree Students 7 Credits and Course Layout 8 Study Methods and Grading System 9 MSc Module Selection: 1 or 2 Term Exchange 10 Course Selection: Double Degrees 11 The Aston Edge (MSc Double Degree) 12 Induction and Erasmus Form Details 13 Conditions for Eligibility 14 Practical Information Visas and Health Insurance 16 Accommodation 17 Support Facilities 20 Student Life at Aston 21 Employments and Careers Services 22 Health and Well Being at Aston 23 Academic Information Important Dates APPLICATION DEADLINES The nomination deadline for the fall term will be 1 June 2019 and the application deadline will be 20 June 2019 for double degree and Term 1 exchange students. -

The Open University MBA 2015/2016 Foreword by Professor Rebecca Taylor, Dean, OU Business School (OUBS)

The Open University MBA 2015/2016 Foreword by Professor Rebecca Taylor, Dean, OU Business School (OUBS) The global marketplace is more challenging than ever before. Organisations need executives who are agile, resilient and can work across boundaries; who can understand the theory of management and business and apply this in the real world; and who can spot and react to new threats and opportunities. These are the executives who will drive growth and success in the future. At the OU Business School, we offer a cutting-edge, practice-based MBA programme developed by leading business academics. We work alongside businesses and our students to deliver an MBA that builds executive business skills while you continue to operate in the workplace. This ensures that you critically assess and apply new skills as they are learned and it means that we can support you in taking the next step in your career. The OU’s vast experience of developing study programmes, allied with our individual approach to business education, enables the OU Business School to offer a tailored and effective MBA that is uniquely placed to assist you in your journey to becoming a highly effective executive. This allows sponsoring employers to see an immediate return on investment while also helping to retain valued and skilled individuals. 3 Values, vision and mission The OU Business School has over 30 years’ experience in helping businesses and ambitious executives across the globe achieve their true potential through innovative practice-based study programmes. Our values Responsive By listening to students and organisations we have been able to: Inclusive • respond to the needs of individuals, employers and the communities in which they live and work Our ability to offer a wide range of support services to students and a championing of ethical standards means that we are • dedicate resources to support our students’ learning success. -

Your Passport to University in the Uk

YOUR PASSPORT TO UNIVERSITY IN THE UK kaplanpathways.partners/aston YOU’LL ENJOY: YOUR ROUTE TO A • Complete preparation for your degree • Guaranteed entry to LIFE-CHANGING DEGREE Aston University* If you don’t quite qualify for a degree at Aston University, you can still gain • Access to university facilities in London entry with a pathway course at Kaplan International College (KIC) London. • Dedicated support services It’s your very own passport to university. • High-quality accommodation FOR STUDENTS WHO HAVE COMPLETED HIGH SCHOOL WITH GOOD GRADES PROGRESS TO 1 OF 30+ DEGREES AT ASTON Graduate International Bachelor’s Bachelor’s Subject areas include: Year One degree year 2 degree year 3 with a degree from Aston • Accounting at KIC London at university at university University • Business Analytics • Design Engineering • Electronic Engineering FOR STUDENTS WITH A BACHELOR’S DEGREE OR EQUIVALENT • Finance • Human Resources • Investment Analysis Master’s Graduate • Management Pre-Master’s degree with a degree • Marketing at KIC London 1 year at from Aston • Mechanical Engineering university University • Strategic Marketing • Supply Chain Management + many more * When you pass your KIC London pathway course at the required level and with good attendance WHY STUDY AT ASTON UNIVERSITY? Top 20 in the UK for student experienceT1 2nd in the UK for teaching effectivenessT2 Globally elite Business School, with triple accreditation Top 20 in the UK for graduate prospectsC Excellent location in Birmingham city centre Business Top 20 in the UKT1 MASUD FROM BANGLADESH MASTER’S IN HUMAN Marketing RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND BUSINESS 12th in the UKC “Aston University is an excellent place to study, with great resources. -

Course Entry Requirement Statement for 2021 Entry

Course Entry Requirements Statement for 2021 Entry Course Entry Requirement Statement for 2021 Entry Contents Scope and Purpose ........................................................................................ 3 UK QUALIFICATIONS ......................................................................................... 4 GCSEs and equivalent qualifications .................................................................... 4 A’Levels and equivalent qualifications ................................................................. 4 EU AND INTERNATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS .............................................................. 19 Maritime Courses ........................................................................................ 31 ENGLISH LANGUAGE REQUIREMENTS .................................................................... 29 APPENDIX A: EXEMPTIONS AND EXCEPTIONS ......................................................... 29 APPENDIX B: ACCEPTABLE ENGLISH LANGUAGE QUALIFICATIONS FOR STUDENTS REQUIRING A STUDENT ROUTE VISA ................................................................................... 32 APPENDIX C: EUROPEAN SCHOOL LEAVING/MATRICULATION CERTIFICATES EQUIVALENT TO IELTS (ACADEMIC) 6.0 OVERALL ....................................................................... 38 External Relations | Admissions and Enrolment 2 Updated April 2021 Course Entry Requirements Statement for 2021 Entry Scope and Purpose 1. This document is designed for use by Solent University (SU) staff when evaluating applicants for entry -

Conference Programme

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Please refer to session descriptions for further information about the workshops Monday 20th July 2.00pm – 5.00pm Registration and networking Session This is an opportunity register for the conference, meet and network with other delegates and NADP Directors, gather information about the conference and the City of Manchester Delegates arriving on Tuesday 21st July should first register for the conference. The Registration Desk will be open from 8.00am. Tuesday 21st July 9.00am – 9.30am Welcome to the conference Paddy Turner, Chair of NADP Professor Dame Nancy Rothwell, President of University of Manchester 9.30am – 10.15am Keynote Presentation Scott Lissner, AHEAD and Ohio State University 10.15am – 10.45am Refreshment break 10.45am – 11.45am Parallel workshop session 1 Workshop 1 Inclusive HE beyond borders Claire Ozel, Middle East Technical University, Turkey Workshop 2 Emergency preparedness: maintaining equity of access Stephen Russell, Christchurch Polytechnic, New Zealand Workshop 3 Supporting graduate professional students: an overview of an independent disability services programme with an emphasis on mental illness Laura Cutway and Mitchell C Bailin, Georgetown University Law Centre. USA This programme may be subject to change Workshop 4 This workshop will consist of two presentations Disabled PhD students reflections on living and learning in an academic pressure cooker and the need for a sustainable academia Dieuwertje Dyi Juijg, University of Manchester Great expectations? Disabled students post- graduate -

The Ulster-Scots Language in Education in Northern Ireland

The Ulster-Scots language in education in Northern Ireland European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning hosted by ULSTER-SCOTS The Ulster-Scots language in education in Northern Ireland c/o Fryske Akademy Doelestrjitte 8 P.O. Box 54 NL-8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands T 0031 (0) 58 - 234 3027 W www.mercator-research.eu E [email protected] | Regional dossiers series | tca r cum n n i- ual e : Available in this series: This document was published by the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Ladin; the Ladin language in education in Italy (2nd ed.) and Language Learning with financial support from the Fryske Akademy and the Province Latgalian; the Latgalian language in education in Latvia of Fryslân. Lithuanian; the Lithuanian language in education in Poland Maltese; the Maltese language in education in Malta Manx Gaelic; the Manx Gaelic language in education in the Isle of Man Meänkieli and Sweden Finnish; the Finnic languages in education in Sweden © Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Mongolian; The Mongolian language in education in the People’s Republic of China and Language Learning, 2020 Nenets, Khanty and Selkup; The Nenets, Khanty and Selkup language in education in the Yamal Region in Russia ISSN: 1570 – 1239 North-Frisian; the North Frisian language in education in Germany (3rd ed.) Occitan; the Occitan language in education in France (2nd ed.) The contents of this dossier may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, Polish; the Polish language in education in Lithuania provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to the Mercator European Romani and Beash; the Romani and Beash languages in education in Hungary Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning. -

Lancaster University

RCUK PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT WITH RESEARCH: SCHOOL-UNIVERSITY PARTNERSHIPS INITIATIVE (SUPI) FINAL REPORT - LANCASTER UNIVERSITY SUPI PROJECT NAME: INSPIRING THE NEXT GENERATION NAMES OF CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS REPORT: Ann-Marie Houghton, Jane Taylor, Alison Wilkinson, Catherine Baxendale, Stephanie Bryan, Sharon Huttly Glossary of terms: BOX refers to Research in a BOX which come in a variety of forms, e.g. PCR in a Box, Moot in a Box, Design in a Box, Diet in a Box. EPO Enabling, Process and Outcome indicators used as part of the evaluation framework to identify reasons for success and greater understanding of the challenges encountered, (EPO model developed by Helsby and Saunders 1993) EPQ Extended Project Qualification ECR Early Career Researchers who include PhD, Postdoc and Research Associates LUSU Lancaster University Students’ Union PIs Principle Investigators QES Queen Elizabeth School, Teaching School Alliance including 10 schools who have engaged in activities during the lifetime of Lancaster’s SUPI RinB refers to Research in a BOX which come in a variety of forms, e.g. PCR in a Box, Moot in a Box, Design in a Box, Diet in a Box. SLF South Lakes Federation of which QES is a member, an established strategic network SUPI School University Partnership Initiative funded by RCUK SURE School University Research Engagement the RCUK SUPI legacy project which will include EPQ, Research in a BOX, TURN, and the Brilliant Club, activities developed during the SUPI project TURN Teacher University Research Network that will be one of the SURE project activities UKSRO: Lancaster University’s UK Student Recruitment and Outreach team who have responsibility for marketing, recruitment and widening access outreach. -

The Aston Mba

THE ASTON MBA GET THE EDGE TO SUCCEED ASTONMBA.COM TRIPLE ACCREDITED 02 The Aston MBA Aston Business School 03 CONTENTS 04 Creating tomorrow’s leaders today 06 Birmingham and Aston life 08 The Aston Edge 10 Getting The Edge 12 With you all the way: induction and learning approach 14 With you all the way: career and alumni support 16 Designed for success 18 MBA core modules 20 Real world results 22 Study routes - Full-time 24 Study routes - Online 26 Study routes - Executive Part-time 28 Entry requirements and admissions information 30 How to apply 04 Aston Business School The Aston MBA CREATING TOMORROW’S LEADERS TODAY The Aston MBA is an intensive programme designed for professionals who have already made their mark in business and are ready to take their careers to the next level. It draws on our world-leading Triple accredited The most rewarding MBA business research and our global We are in the top one per cent of Our full-time MBA was ranked 1st network of corporate connections business schools worldwide with in the UK and 2nd in the world to transform you into a dynamic triple accreditation from AMBA, for return on investment by The and agile business leader. AACSB and EQUIS, the leading Economist (Good-value MBAs 2014). accreditation bodies for business Our programme enables you schools in the UK, USA and Europe. to gain a critical perspective on Globally recognised your own management style and For more than 60 years we have World leading the insight to move your career conducted pioneering research forward, giving you new skills, 100 per cent of our business into contemporary business opportunities and connections. -

1. Introduction

THE UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS Code of Practice on Learning Analytics 1. Introduction Learning Analytics is defined as follows: "the measurement, collection, analysis, and reporting of data about learners and their contexts, for the purposes of understanding and optimising learning and the environments in which it occurs." (International Conference on Learning Analytics, 2011). The University of Leeds has adopted this definition for the purposes of this Code of Practice and the Learning Analytics Strategy. The University of Leeds uses learning analytics to enhance taught student education and support student success for registered students. The University will use learning analytics to: (i) support individual learners – through actional intelligence for students, teachers and professional staff; (ii) help understand cohort behaviours and outcomes; (iii) help understand and enhance the learning environment. This means that we will gather and analyse data relating to students’ education and present these in appropriate formats to staff and students, to support students’ learning, progress and well-being. The University recognises that data on their own cannot provide a complete picture of a student’s progress, but provide an indicative picture of progress and likelihood of success. This document sets out the responsibilities for staff, students and the University to ensure that learning analytics is carried out responsibly, transparently, appropriately and effectively, addressing the key legal, ethical and logistical issues which are likely to arise. This not only covers the presentation of learning analytics data to students and staff but also possible use in research projects and management information. It is important to note that the University currently holds and processes the data sources identified in this document. -

The BBA in Management

BBA (HONS) INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT A GUIDE TO YEARS 1 & 2 2019/2020 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION & THE BBA IBM TEAM ................................................................... ………………….…..…2 USEFUL CONTACTS ..................................................................................................... …………………….…3 LUSIPBS, ACCOMMODATION .......................................................................................... …………...….…4 THE ACADEMIC YEAR & ATTENDANCE ............................................................... …............................…5 INTERNSHIPS ............................................................................................................ ……………………..….6 PROGRAMME STRUCTURE PART I, YEAR 1………………………………………………………………………………………7 COMPULSORY MODULES YEAR 1 .............................................................................. ……………………..…7 PROGRAMME STRUCTURE PART II, YEAR 2….……………………………………………………………………………….11 COMPULSORY MODULES YEAR 2………………….………………………………………………………………………………12 US LINK OPTIONAL MODULES YEAR 2..………..………………………………………………………………………………14 LANGUAGE MODULES……………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………..16 EU LINK OPTIONAL MODULES YEAR 2……………..…………………………………………………………………….…….17 ACCOUNTING & FINANCE……………………………………………………………………………………..17 ECONOMICS………………………………………………………………………………………………………….17 ENTREPRENEURSHIP, STRATEGY & INNOVATION………………………………………………….20 MARKETING………………………………………………………………………………………………………….20 MANAGEMENT SCIENCE………………………………………………………………………………….……20 ORGANISATION, WORK & TECHNOLOGY………………………………………………………………22 -

Open University Registration Form

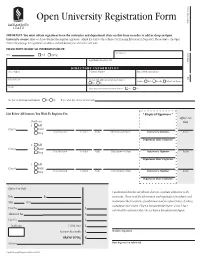

Student’s Last Name Student’s Open University Registration Form IMPORTANT: You must obtain signatures from the instructor and department chair on this form in order to add or drop an Open University course. After you have obtained the required signatures, submit the form to the College of Continuing Education in Napa Hall. Please refer to the Open University web page for registration deadlines and withdrawal procedures for each term. PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY ALL INFORMATION BELOW: Sac State ID First Name Year: Fall Spring Legal Name (Last, First, MI) DIRECTORY INFORMATION Street Address Telephone Number Date of Birth (mm/dd/yy) M.I. City, State, Zip Do you currently have a bachelor’s degree? Gender: Male Female Other/Non-Binary Yes No Email Have you ever attended Sac State classes? Yes No Are you an International Student? Yes No If yes, what type of visa do you hold? List Below All Courses You Wish To Register For: * Required Signatures * Office Use Check one Only 1. Add Class # Audit Drop Dept. & Course# Section # Units Print Instructor’s Name Instructor’s Signature Initials Department Chair's Signature 2. Add Class # Audit Drop Dept. & Course# Section # Units Print Instructor’s Name Instructor’s Signature Initials Department Chair's Signature 3. Add Class # Audit Drop Dept. & Course# Section # Units Print Instructor’s Name Instructor’s Signature Initials Department Chair's Signature Office Use Only I understand that this enrollment does not constitute admission to the Date By university. I have read the information and registration procedures and REG CON understand the procedures of withdrawal and fee refund policy.