Fife and Drum Mar 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medical Care of American Pows During the War of 1812

Canadian Military History Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 5 2008 Medical Care of American POWs during the War of 1812 Gareth A. Newfield Canadian War Museum, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Newfield, Gareth A. "Medical Care of American POWs during the War of 1812." Canadian Military History 17, 1 (2008) This Canadian War Museum is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Newfield: Medical Care of POWs Medical Care of American POWs during the War of 1812 Gareth A. Newfield n 2005, a service in Halifax upkeep was difficult, rendering medical Icommemorated US soldiers and care often chaotic. British medical sailors who perished in Britain’s Melville officers none the less cared for captives Island prisoner-of-war camp during adequately and comparably to the way the War of 1812 and whose remains they assisted their own forces. now lie on Deadman’s Island, a nearby peninsula. The service culminated Organization nearly a decade of debate, in which local Processing the Sick and history enthusiasts, the Canadian and Wounded American media, and Canadian and US politicians rescued the property ew formal conventions dealt with the from developers. The media in particular had Ftreatment of prisoners of war during highlighted the prisoners’ struggles with disease the period. While it was common for combatant and death, often citing the sombre memoirs of nations to agree upon temporary conventions survivors.1 Curiously, Canadian investigators once hostilities commenced, generally it was relied largely upon American accounts and did quasi-chivalric sentiments, notions of Christian little research on efforts at amelioration from the conduct, and a sense of humanitarian obligation British perspective. -

Canadian Archæology. an Essay

UC-NRLF Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.archive.org/details/canadianarcholOOkingrich : Canadian Archeology, AN ESSAY. WILLIAM KIXGSFORD. MONTREAL WM. DRYSDALE & CO., 232 ST. JAMES STREET. 1886. ! ! Ach Gott ! die Kunst ist lang, Und kurz ist unser Leben. Mir wird, bei meinem kritischen Bestreben, Doch oft um Kopf und Busen bang. Wie schwer sind niclit die Mittel zu erwerben, Durch die man zu den Quellen steigt Und eh' man nur den halben Weg erreicht Musz wohl eiu armer Teufel sterben. Goethe, Faust. Ah me ! but art is long And human life is short. Oft in the throes of critic thought Have head and heart ceased to be strong. How hard the means which in our effort lie To reach the sources of what mortals know, But ere a man can half the distance go Verily, poor devil, must he die. Your home born projects prove ever the best ; they are so easy and familiar ; they put too much learning in their things now-a-days. Ben Johnson, Bartholomew Fair, Ist das Licht das Eigenthum der Flamme, wo nicht gar des Ker- zendochts? Ich enthalte mich jedes Urtheils liber solche Frage, und freue mich nur dariiber, dass Ihr dem armen Dochte, der sich brennend verzehrt, eine kleine Vergiitung verwilligen wolt fiir sein groszes gemeinnittziges Beleuchtungsverdienst Heine. Is the light the property of the flame, if it in no wa,Y be of the taper wick ? I abstain from any judgment over such a question, and I only rejoice that you are willing to make some slight amends to the poor wick, which consumes itself in burning, for its noble, universal, merit- orious service of enlightenment ! Canadian Archeology. -

Provincial Plaques Across Ontario

An inventory of provincial plaques across Ontario Last updated: May 25, 2021 An inventory of provincial plaques across Ontario Title Plaque text Location County/District/ Latitude Longitude Municipality "Canada First" Movement, Canada First was the name and slogan of a patriotic movement that At the entrance to the Greater Toronto Area, City of 43.6493473 -79.3802768 The originated in Ottawa in 1868. By 1874, the group was based in Toronto and National Club, 303 Bay Toronto (District), City of had founded the National Club as its headquarters. Street, Toronto Toronto "Cariboo" Cameron 1820- Born in this township, John Angus "Cariboo" Cameron married Margaret On the grounds of his former Eastern Ontario, United 45.05601541 -74.56770762 1888 Sophia Groves in 1860. Accompanied by his wife and daughter, he went to home, Fairfield, which now Counties of Stormont, British Columbia in 1862 to prospect in the Cariboo gold fields. That year at houses Legionaries of Christ, Dundas and Glengarry, Williams Creek he struck a rich gold deposit. While there his wife died of County Road 2 and County Township of South Glengarry typhoid fever and, in order to fulfil her dying wish to be buried at home, he Road 27, west of transported her body in an alcohol-filled coffin some 8,600 miles by sea via Summerstown the Isthmus of Panama to Cornwall. She is buried in the nearby Salem Church cemetery. Cameron built this house, "Fairfield", in 1865, and in 1886 returned to the B.C. gold fields. He is buried near Barkerville, B.C. "Colored Corps" 1812-1815, Anxious to preserve their freedom and prove their loyalty to Britain, people of On Queenston Heights, near Niagara Falls and Region, 43.160132 -79.053059 The African descent living in Niagara offered to raise their own militia unit in 1812. -

The Historical Significance of General Sir Isaac Brock: Part 2

War of 1812, Historical Thinking Lesson 12 The Historical Significance of General Sir Isaac Brock: Part 2 by Elizabeth Freeman-Shaw Suggested grade level: Intermediate/Senior Suggested time: 2 class periods Brief Description of the Task In this lesson students will explore why General Sir Isaac Brock is considered to be historically significant, and wrestle with whether or not he should be. Historical Thinking Concepts • Historical Significance • Use of Evidence (primary and secondary) Learning Goals Students will be able to: • participate in an activity that allows them to understand the concept of historical significance • identify the role and historical significance of General Sir Isaac Brock in the War of 1812 • review secondary accounts of Isaac Brock to determine the case for significance • synthesize data into qualities of greatness • use excerpts from primary sources to determine the validity of historians’ conclusions. Materials Each student will need copies of all Primary Sources and Worksheets (in the Appendices file). Prior Knowledge It would be an asset for students to be familiar with: The Historical Thinking Project, 2012 War of 1812, Historical Thinking Lesson 12 1. Earlier events leading up to the declaration of war, key personalities, the political structure of British North America, and the causes of the war. 2. The concept of historical significance (See The Historical Thinking Project website, http://www.historicalthinking.ca/concept/historical- significance) Assessment Students may be evaluated based on the work completed with: • Worksheet 1 – Decoding Secondary Sources • Worksheet 2 – Note-taking, Secondary Sources • Worksheet 3 – Examining Primary Sources Detailed Lesson Plan Focus Question: Why is it that even though General Brock was killed in the early hours of the Battle of Queenston Heights and Colonel Roger Sheaffe lead the British forces to victory, Brock is more remembered than Sheaffe? Part A – Exploring a Controversy 1. -

Brockton's Name Recalls Isaac Brock's Cousin James

The Newsletter of the Friends of Fort York and Garrison Common v. 13 No. 1 Mar. 2009 1 Brockton’s Name Recalls Isaac Brock’s 6 Administrator’s Report Cousin James 6 Council Approves Design Team for 3 Henry Bowyer Lane’s Fort at Toronto, 1842 June Callwood Park 3 Conversation with Colin Upton 7 First Steps to Renewing the Fort 4 In Review 8 Upcoming Events 5 New Committee Chair Brockton’s Name Recalls Isaac Brock’s Cousin James Dan Brock, John England, Gillian Lenfestey, Stephen Otto, Guy St-Denis and Stuart Sutherland contributed to this article. Many ordinary people enjoy more than Andy Warhol’s fifteen minutes of fame before resuming their modest lives. James Brock’s time in the limelight of Upper Canada lasted about fifteen months from October 1811 until late 1812, but left a lasting mark on Toronto. Paradoxically, his imprint on the city in the name of ‘Brockton’ has proven more indelible than Brock Street, as lower Spadina was called until 1884 in honour of his famous kinsman, Sir Isaac Brock. Frequently said to be Isaac’s brother or nephew, James was actually a first cousin. Isaac’s father John and James’s father Henry were brothers. James was born at St. Peter Port, Guernsey, on April 3 1773, to Henry Brock and Suzanne de Sausmarez, both members of prominent families. He was raised in comfortable circumstances in “Belmont,” a large house with extensive grounds, and likely began his education in one of the local clergy-run schools where he was taught in French, the working language on the island until the late 19th century. -

ONTARIO (Canada) Pagina 1 Di 3 ONTARIO Denominato Dal Lago Ontario, Che Prese Il Suo Nome Da Un Linguaggio Nativo Americano

ONTARIO (Canada) ONTARIO Denominato dal Lago Ontario, che prese il suo nome da un linguaggio nativo americano, derivante da onitariio=lago bellissimo, oppure kanadario=bellissimo, oppure ancora dall’urone ontare=lago. A FRANCIA 1604-1763 A GB 1763-1867 - Parte del Quebec 1763-1791 - Come Upper Canada=Canada Superiore=Alto Canada 24/08/1791-23/07/1840 (effettivamente dal 26/12/1791) - Come Canada Ovest=West Canada 23/07/1840-01/07/1867 (effettivo dal 5/02/1841) (unito al Canada Est nella PROVINCIA DEL CANADA) - Garantito Responsabilità di Governo 11/03/1848-1867 PROVINCIA 1/07/1867- Luogotenenti-Governatori GB 08/07/1792-10/04/1796 John GRAVES SIMCOE (1752+1806) 20/07/1796-17/08/1799 Peter RUSSELL (f.f.)(1733+1808) 17/08/1799-11/09/1805 Peter HUNTER (1746+1805) 11/09/1805-25/08/1806 Alexander GRANT (f.f.)(1734+1813) 25/08/1806-09/10/1811 Francis GORE (1°)(1769+1852) 09/10/1811-13/10/1812 Sir Isaac BROCK (f.f.)(1769+1812) 13/10/1812-19/06/1813 Sir Roger HALE SHEAFFE (f.f.)(1763+1851) 19/06/1813-13/12/1813 Francis DE ROTTENBURG, BARON DE ROTTENBURG (f.f.) (1757+1832) 13/12/1813-25/04/1815 Sir Gordon DRUMMOND (f.f.)(1771+1854) 25/04/1815-01/07/1815 Sir George MURRAY (Provvisorio)(1772-1846) 01/07/1815-21/09/1815 Sir Frederick PHILIPSE ROBINSON (Provvisorio)(1763+1852) 21/09/1815-06/01/1817 Francis GORE (2°) 11/06/1817-13/08/1818 Samuel SMITH (f.f.)(1756+1826) 13/08/1818-23/08/1828 Sir Peregrine MAITLAND (1777+1854) 04/11/1828-26/01/1836 Sir John COLBORNE (1778+1863) 26/01/1836-23/03/1838 Sir Francis BOND HEAD (1793+1875) 05/12/1837-07/12/1837 -

The Many Faces of Fort George National Historic Site of Canada: Insights Into a Historic Fort’S Transformation

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 44 Special Issue: War of 1812 Article 7 2015 The aM ny Faces of Fort George National Historic Site of Canada: Insights into a Historic Fort’s Transformation Barbara Leskovec Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Leskovec, Barbara (2015) "The aM ny Faces of Fort George National Historic Site of Canada: Insights into a Historic Fort’s Transformation," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 44 44, Article 7. Available at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol44/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Northeast Historical Archaeology/Vol. 44, 2015 119 The Many Faces of Fort George National Historic Site of Canada: Insights into a Historic Fort’s Transformation Barbara Leskovec Fort George National Historic Site of Canada is situated in the picturesque town of Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, Canada. Constructed by the British following the capitulation of Fort Niagara, Fort George is of national historic significance because it served as the Headquarters of the Central Division of the British Army, and played a crucial role in the defence of Upper Canada during the War of 1812. Archaeological investigations in the last 50 years have shed light on the fort’s early structures and modifications. In 2009, funding allocated through the Federal Economic Action Plan provided an opportunity to further explore the fort’s historic transformation. -

Poles in the Regiment De Watteville and Regiment De Meuron During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 Magazine Issue 18, June 2012 From the Battlegrounds of Canada to the Red River Colony: Poles in the Regiment De Watteville and Regiment De Meuron during the War of 1812 By Stan Skrzeszewski and Amanda Jankowski Uniform of Captain Jean Ployart, De Watteville Regiment. More than 500 Poles served in this regiment during the War of 1812. The uniform is on display at Fort George, Niagara-on-the-Lake (Christoff’s Gallery took all the photographs in this article) Introduction This project started from the premise that any good war that came after the elimination of Poland from the map of Europe in 1795 had to include some Poles. Since that time there have been no major wars that have not included Poles fighting for freedom. In 1794 after the defeat of the Kościusko uprising many Polish patriots went forth following the slogan that took them all the way to the Battle of Monte Cassino in 1944 “to fight for our freedom and yours.”1 I was not disappointed when I applied this assumption to the War of 1812 in North America. A substantial number of Poles took part. Most of the written history on the War of 1812 was and is done from two perspectives – the British/Canadian and the American. Very little of the written history reflects the perspective of the Native peoples who were major participants in the war, the Black participants and the Coloured Corps and the numerous Europeans who also fought in the conflict. This paper can be said to bring a Slavic perspective to the War of 1812, but it also brings in other marginalized warriors in curious ways. -

Museum HLF Development Update

2016-2017 In this issue: Friends of The ·HLF Development ·Website update ·Artwork Conservation ·Foster Medal Collection ·Rothbury Trenches ·Visitors, Volunteers and Activities ·General Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe ·Upcoming Lectures Museum HLF Development Update His Grace the Duke of Upstairs, Downstairs Northumberland formally A special virtual tour of the reopened the museum on museum's three floors has 24th of June 2016, the increased the accessibility of the Anniversary of the Battle of displays for everyone. Wilhelmstahl (1762), at a Reception to celebrate Filmed by InfoAktiv, the tour completion of the new allows visitors who are unable to displays on the two upper manage the stairs to visit the floors and to thank our upper floors at the touch of a funders and everyone who screen. Touching one of the virtual worked on the project. tour's 15 'hot spots‘ brings up a rotating image of the selected The first phase of the object together with information redevelopment was a special about it. centenary exhibition commemorating the role of “An excellent museum, my the Northumberland Fusiliers wife was fascinated” Visitor in the First World War. It was survey comment, June 2017 presented on the ground floor for three seasons from 2014. “The Fusiliers museum is Aden remembered excellent and makes you 2017 marks the 50th proud” eldorado2015, Anniversary of the Aden Tripadvisor, summer 2015 Mutiny. “Incident on Temple Cliffs” by The final phase is now Terence Cuneo depicts the complete, retelling the actions of Fusilier John Duffy Regiment’s 350 year history who was awarded the with themes representing the Distinguished Conduct Medal for everyday life of a soldier over rescuing the pilot of a helicopter three floors of new displays. -

6 Dec 2013 Brown & Lake Ontario

Pike National Historic Trail Association Newsletter zebulonpike.org December 2013 Vol. 7 No 6 Browns Canyon & Exploring of the Arkansas River Headwaters Dec. 1806 www. by Allan Vainley On Wednesday, December 10, 1806, Pike had decided to leave the Cañon City, CO stockade site to travel north to explore what is now southern South Park, CO. They discovered the South Platte headwaters. After leaving their “Hartsel (Santa Maria)” site, they traveled southwest down Trout Creek into the Arkansas River Valley to the mouth Our website is Our website of Trout Ck. (Arkansas River) just south of Buena Vista on Dec. 19 in the light of the snow-capped 14,000 ft Collegiate Mountain range. On Dec. 20, he wrote: “As there was no prospect of killing any game, it was necessary that the party should leave that place, I therefore determined that the doctor and Baroney should descend the river in the morning; that myself and two men (Miller and Mountjoy) would ascend and the rest of the party descend after the doctor until they obtained provision and could wait for me.” On Dec. 22, the three found the headwaters of the “Arkansaw”. On the 23rd they marched early back south down river and “at two oʼclock, P.M. discovered the trace of the party” and followed it into Brownʼs Canyon, “until some time in the night, when we arrived at the second nights encampment of the party. Our cloathing was frozen stiff, and we ourselves were considerably benumbed.” The encampment was beside the confluence of Brownʼs Creek and the Arkansas in Browns Canyon. -

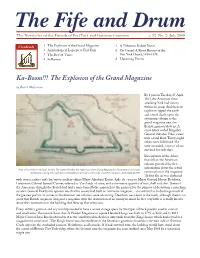

The Explosion of the Grand Magazine

The Newsletter of the Friends of Fort York and Garrison Common v. 12 No. 2 July 2008 1 The Explosion of the Grand Magazine 5 A Tribute to Robert Nurse 3 Archaeological Legacies at Fort York 6 On Guard: A Short History of the 3 The Best of Times Fort York Guard, 1934-1978 8 4 In Review Upcoming Events Ka-Boom!!! The Explosion of the Grand Magazine by Robert Malcomson By 1 pm on Tuesday, 27 April 1813, the American force attacking York had victory within its grasp. And then an explosion ripped the earth and rained death upon the advancing column as the grand magazine near the British garrison blew up. A stone block ended Brigadier General Zebulon Pike’s career with a fatal blow. Thirty-eight others were killed and 224 were wounded, some of whom survived for only days. Descriptions of the debris that fell on the American column provided the first Plan of Fort York 1816, by G. Nicolls. The crater left after the explosion of the Grand Magazine is illustrated as a circular information about the actual indentation along the south west embankment directly south of the southern ramparts. (LAC, NMC 23139) construction of the magazine. ‘At first the air was darkened with stones, rafters and clay,’ wrote artillery officer Major Abraham Eustis. Aide-de-camp to Major General Henry Dearborn, Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Conner, referred to ‘Cart loads of stone, and an immense quantity of iron, shell and shot.’ Some of the Americans thought the British had laid a mine beneath the approach to the garrison for the purpose of destroying a marching column. -

The True Face of Sir Isaac Brock

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2018-10 The True Face of Sir Isaac Brock St-Denis, Guy University of Calgary Press St-Denis, G. (2018). The True Face of Sir Isaac Brock. Calgary, AB. University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/108892 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca THE TRUE FACE OF SIR ISAAC BROCK by Guy St-Denis ISBN 978-1-77385-021-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence.