Roma in Lima: Italian Renaissance Influence in Colonial Peruvian Painting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Centro Cultural De La Raza Archives CEMA 12

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g No online items Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives CEMA 12 Finding aid prepared by Project director Sal Güereña, principle processor Michelle Wilder, assistant processors Susana Castillo and Alexander Hauschild June, 2006. Collection was processed with support from the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS). Updated 2011 by Callie Bowdish and Clarence M. Chan UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Email: [email protected]; URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections © 2006 Centro Cultural de la Raza CEMA 12 1 Archives CEMA 12 Title: Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 12 Contributing Institution: UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 83.0 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1970-1999 Abstract: Slides and other materials relating to the San Diego artists' collective, co-founded in 1970 by Chicano poet Alurista and artist Victor Ochoa. Known as a center of indigenismo (indigenism) during the Aztlán phase of Chicano art in the early 1970s. (CEMA 12). Physical location: All processed material is located in Del Norte and any uncataloged material (silk screens) is stored in map drawers in CEMA. General Physical Description note: (153 document boxes and 5 oversize boxes). creator: Centro Cultural de la Raza (San Diego, Calif.). Access Restrictions None. Publication Rights Copyright resides with donor. Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All Requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. -

Gawc Link Classification FINAL.Xlsx

High Barcelona Beijing Sufficiency Abu Dhabi Singapore sufficiency Boston Sao Paulo Barcelona Moscow Istanbul Toronto Barcelona Tokyo Kuala Lumpur Los Angeles Beijing Taiyuan Lisbon Madrid Buenos Aires Taipei Melbourne Sao Paulo Cairo Paris Moscow San Francisco Calgary Hong Kong Nairobi New York Doha Sydney Santiago Tokyo Dublin Zurich Tokyo Vienna Frankfurt Lisbon Amsterdam Jakarta Guangzhou Milan Dallas Los Angeles Hanoi Singapore Denver New York Houston Moscow Dubai Prague Manila Moscow Hong Kong Vancouver Manila Mumbai Lisbon Milan Bangalore Tokyo Manila Tokyo Bangkok Istanbul Melbourne Mexico City Barcelona Buenos Aires Delhi Toronto Boston Mexico City Riyadh Tokyo Boston Munich Stockholm Tokyo Buenos Aires Lisbon Beijing Nanjing Frankfurt Guangzhou Beijing Santiago Kuala Lumpur Vienna Buenos Aires Toronto Lisbon Warsaw Dubai Houston London Port Louis Dubai Lisbon Madrid Prague Hong Kong Perth Manila Toronto Madrid Taipei Montreal Sao Paulo Montreal Tokyo Montreal Zurich Moscow Delhi New York Tunis Bangkok Frankfurt Rome Sao Paulo Bangkok Mumbai Santiago Zurich Barcelona Dubai Bangkok Delhi Beijing Qingdao Bangkok Warsaw Brussels Washington (DC) Cairo Sydney Dubai Guangzhou Chicago Prague Dubai Hamburg Dallas Dubai Dubai Montreal Frankfurt Rome Dublin Milan Istanbul Melbourne Johannesburg Mexico City Kuala Lumpur San Francisco Johannesburg Sao Paulo Luxembourg Madrid Karachi New York Mexico City Prague Kuwait City London Bangkok Guangzhou London Seattle Beijing Lima Luxembourg Shanghai Beijing Vancouver Madrid Melbourne Buenos Aires -

Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 7 Number 2 Pervuvian Trajectories of Sociocultural Article 13 Transformation December 2013 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Silva, Ernesto (2013) "Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 7 : No. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol7/iss2/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emesto Silva Journal of Global Initiatives Volume 7, umber 2, 2012, pp. l83-197 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva 1 The aim of this essay is to provide a panoramic socio-historical overview of Peru by focusing on two periods: before and after independence from Spain. The approach emphasizes two cultural phenomena: how the indigenous peo ple related to the Conquistadors in forging a new society, as well as how im migration, particularly to Lima, has shaped contemporary Peru. This contribu tion also aims at providing a bibliographical resource to those who would like to conduct research on Peru. -

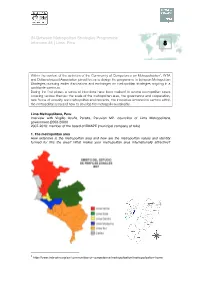

IN-Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme Interview #8 | Lima, Peru 8

IN-Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme Interview #8 | Lima, Peru 8 Within the context of the activities of the Community of Competence on Metropolisation1, INTA and Deltametropool Association joined forces to design the programme In-between Metropolitan Strategies pursuing earlier discussions and exchanges on metropolitan strategies ongoing in a worldwide spectrum. During the first phase, a series of interviews have been realised to several metropolitan cases covering various themes: the scale of the metropolitan area, the governance and cooperation, new forms of urbanity and metropolitan environments, the innovative economical sectors within the metropolitan area and how to develop the metropolis sustainably. Lima Metropolitana, Peru Interview with Virgilio Acuña Peralta, Peruvian MP, councillor of Lima Metropolitana government (2003-2006) 2007-2010: member of the board of EMAPE (municipal company of tolls) 1.! The metropolitan area How extensive is the metropolitan area and how are the metropolitan values and identity formed for this the area? What makes your metropolitan area internationally attractive? 1 http://www.inta-aivn.org/en/communities-of-competence/metropolisation/metropolisation-home In Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme – Interview 7 Lima Metropolitana counts 9 millions inhabitants (including the Province of Callao) and 42 districts. The administrative region of Lima Metropolitana (excluding Callao) has a total surface of 2800 km2. The metropolitan area has an extension of 150km North-South and 60Km on the West (sea coast) - East (toward the Andes) direction. The development of the city with urban sprawl goes south, towards the seaside resorts, outside of the administrative limits of Lima Metropolitana (Province of Cañete, City of Ica) and to the Northern beach areas. -

Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2018 The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon Christian Calienes The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2526 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon By Christian Calienes A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Earth and Environmental Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 i © 2018 CHRISTIAN CALIENES All Rights Reserved ii The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon by Christian Calienes This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Earth & Environmental Sciences in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Inés Miyares Chair of Examining Committee Date Cindi Katz Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Inés Miyares Thomas Angotti Mark Ungar THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon By Christian Calienes Advisor: Inés Miyares The resistance movement that resulted in the Baguazo in the northern Peruvian Amazon in 2009 was the culmination of a series of social, economic, political and spatial processes that reflected the Peruvian nation’s engagement with global capitalism and democratic consolidation after decades of crippling instability and chaos. -

Art Historic Rapport

15 SOUTH NETHERLANDISH MASTER Antwerp Mannerism, second half of the 16th century Christ bearing the Cross Oak, carved in high relief H. 43 cm. W. 28 cm. D. 13 cm. PROVENANCE Private collection, Brussels, Belgium his impressive sculpture depicts one of the most popular stations form the Passion TCycle: Christ bearing the Cross. In the centre of the composition, Christ is depicted wearing a long, heavy shroud through which his anatomy is clearly viable. On his head he wears the Crown of Thorns. He carries the Cross over his left shoulder. His upper body and arms are tied with ropes. Christ is flanked by two Roman soldiers wearing Classical styled armour, referring to Ancient Rome. The group is composed moving to the right. The soldier who is leading Christ forward holds a knotted rope in his left hand that runs down from Christ’s shoulders over the soldier’s upper leg and a beating-bat in the hand of his twisted right arm. The soldier wears an outstandingly composed helmet that covers most of his face. Visible are his sharp nose and pointy beard, which lend him sturdy features. The soldier who is standing behind Christ wears a feathered Roman helmet together with an impressive suit of armour, which is embellished with elegant decorations in high relief, featuring a Fig.1. Detail striking grotesque1 on his chest. This soldier holds a bat is his right hand, ready to strike. His muscular body and his powerful, violent pose together with ART HISTORIC SIGNIFICANCE his mocking facial expression, form a remarkable contrast with the solemn and submissive pose of This group is a clear expression of Mannerism: the Christ. -

The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Our Lady of Cocharcas

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-1-2020 Performance, Ritual, and Procession: The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Our Lady of Cocharcas Evelin M. Chabot CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/576 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Performance, Ritual, and Procession: The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Our Lady of Cocharcas by Evelin Chabot Griffin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the History of Art, Hunter College The City University of New York 2020 4/27/2020 Professor Tara Zanardi Date Thesis Sponsor 4/26/2020 Professor Maria Loh Date Second Reader Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………..……ii List of Images…………………………………………………………………….………...…iii, iv Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………..……1 Chapter One: Power, Proselytism, and Purpose……………………………………………..……8 Chapter Two: The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Our Lady of Cocharcas…………………….34 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….51 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..54 Images……………………………………………………………………………………………57 i Acknowledgements Professor Tara Zanardi has my deepest gratitude for her patience and wisdom, which helped guide this thesis from its very early stages to where it is now. I am also grateful to Professor Maria Loh for her thorough review of the thesis in its final form and incredibly helpful and incisive input. I want to thank Ronda Kasl, Curator of Latin American Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, for inspiring me to work on these enchanting statue paintings and for her insight and guidance that spring-boarded my research at the beginning of this process. -

UCLA Historical Journal

UCLA UCLA Historical Journal Title Indians and Artistic Vocation in Colonial Cuzco, 1650-1715 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8xh0r92z Journal UCLA Historical Journal, 11(0) ISSN 0276-864X Author Crider, John Alan Publication Date 1991 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Indians and Artistic Vocation in Colonial Cuzco, 1650-1715 John Alan Crider The school of painting that emerged in Cuzco during the second half of the seventeenth century marks one of the more extraordi- nary and unique expressions of colonial art in Spanish America. Thematically and stylistically the paintings are too Christian and urbane to be assigned the status of folk art, yet too tantalizingly "other" to be included in the canon of European art. In the Cuzco paintings Christian iconography is often strikingly reinterpreted. There is an anachronistic preference for flat hieratic figures, remi- niscent of Medieval art, and for archaic methods such as gold-lace gilding. In sum, the paintings of the Cuzco school exhibited a sur- prising fusion of European visual ideas, techniques, and styles. Primarily, this paper is interested in those anonymous Indian artisans who became increasingly active in art production after 1650, when one sees not only greater participation of native Andeans in the official guild, as reflected by contract documents, but eventually their close association with the rise of the unique artistic style which variously has been called the Cuzco school, Andean Baroque, or Andean Mestizaje. No visual representation of space can be divorced from its con- text of intellectual and social values. Indeed, in order to under- stand the circle of art which emanated from colonial Cuzco, and which intersected with the widening circles of influence shed by John Alan Crider received a B.A. -

Old Spanish Masters Engraved by Timothy Cole

in o00 eg >^ ^V.^/ y LIBRARY OF THE University of California. Class OLD SPANISH MASTERS • • • • • , •,? • • TIIK COXCEPTION OF THE VIRGIN. I!V MURILLO. PRADO Mi;SEUAI, MADKIU. cu Copyright, 1901, 1902, 1903, 1904, 1905, 1906, and 1907, by THE CENTURY CO. Published October, k^j THE DE VINNE PRESS CONTENTS rjuw A Note on Spanish Painting 3 CHAPTER I Early Native Art and Foreign Influence the period of ferdinand and isabella (1492-15 16) ... 23 I School of Castile 24 II School of Andalusia 28 III School of Valencia 29 CHAPTER II Beginnings of Italian Influence the PERIOD OF CHARLES I (1516-1556) 33 I School of Castile 37 II School of Andalusia 39 III School of Valencia 41 CHAPTER III The Development of Italian Influence I Period of Philip II (l 556-1 598) 45 II Luis Morales 47 III Other Painters of the School of Castile 53 IV Painters of the School of Andalusia 57 V School of Valencia 59 CHAPTER IV Conclusion of Italian Influence I of III 1 Period Philip (1598-162 ) 63 II El Greco (Domenico Theotocopuli) 66 225832 VI CONTENTS CHAPTER V PACE Culmination of Native Art in the Seventeenth Century period of philip iv (162 1-1665) 77 I Lesser Painters of the School of Castile 79 II Velasquez 81 CHAPTER VI The Seventeenth-Century School of Valencia I Introduction 107 II Ribera (Lo Spagnoletto) log CHAPTER VII The Seventeenth-Century School of Andalusia I Introduction 117 II Francisco de Zurbaran 120 HI Alonso Cano x. 125 CHAPTER VIII The Great Period of the Seventeenth-Century School of Andalusia (continued) 133 CHAPTER IX Decline of Native Painting ii 1 charles ( 665-1 700) 155 CHAPTER X The Bourbon Dynasty FRANCISCO GOYA l6l INDEX OF ILLUSTRATIONS MuRiLLO, The Conception of the Virgin . -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/23/2021 07:29:55PM Via Free Access

journal of jesuit studies 6 (2019) 270-293 brill.com/jjs Catholic Presence and Power: Jesuit Painter Bernardo Bitti at Lake Titicaca in Peru Christa Irwin Marywood University [email protected] Abstract Bernardo Bitti was an Italian Jesuit and painter who traveled to the viceroyalty of Peru at the end of the sixteenth century to make altarpieces in the service of the order’s conversion campaigns. He began his New World career in Lima, the viceregal capital and then, over a span of thirty-five years, traveled to Jesuit mission centers in cities throughout Peru, leaving a significant imprint on colonial Peruvian painting. In 1586, Bitti was in Juli, a small town on Lake Titicaca in southern Peru, where the Jesuits had arrived a decade prior and continually faced great resistance from the local popula- tion. In this paper, I will argue that Bitti’s paintings were tools implemented by the Jesuit missionaries seeking to establish European, Christian presence in the conflicted city. Thus, Bitti’s contribution at Juli can serve as but one example of how the Jesuits used art as part of their methodology of conversion. Keywords Jesuit – Bernardo Bitti – Juli – Peru – missions – colonial painting – viceroyalty – Lake Titicaca In 1576, a small group of Jesuits arrived at the town of Juli in the south of Peru. After a failed attempt by an earlier set of missionaries, and significant hesi- tancy on the part of the Jesuits the evangelization efforts at Juli would eventu- ally come to mark an example of success for other Jesuit sites. Juli presents a fascinating case of Jesuit mission activity because it offers documentation of the indigenous culture’s integration into a newly created Christian town. -

Oficinas Bbva Horario De Atención : De Lunes a Viernes De 09:00 A.M

OFICINAS BBVA HORARIO DE ATENCIÓN : DE LUNES A VIERNES DE 09:00 A.M. a 6:00 P.M SABADO NO HAY ATENCIÓN OFICINA DIRECCION DISTRITO PROVINCIA YURIMAGUAS SARGENTO LORES 130-132 YURIMAGUAS ALTO AMAZONAS ANDAHUAYLAS AV. PERU 342 ANDAHUAYLAS ANDAHUAYLAS AREQUIPA SAN FRANCISCO 108 - AREQUIPA AREQUIPA AREQUIPA PARQUE INDUSTRIAL CALLE JACINTO IBAÑEZ 521 AREQUIPA AREQUIPA SAN CAMILO CALLE PERU 324 - AREQUIPA AREQUIPA AREQUIPA MALL AVENTURA PLAZA AQP AV. PORONGOCHE 500, LOCAL COMERCIAL LF-7 AREQUIPA AREQUIPA CERRO COLORADO AV. AVIACION 602, LC-118 CERRO COLORADO AREQUIPA MIRAFLORES - AREQUIPA AV. VENEZUELA S/N, C.C. LA NEGRITA TDA. 1 - MIRAFLORES MIRAFLORES AREQUIPA CAYMA AV. EJERCITO 710 - YANAHUARA YANAHUARA AREQUIPA YANAHUARA AV. JOSE ABELARDO QUIÑONES 700, URB. BARRIO MAGISTERIAL YANAHUARA AREQUIPA STRIP CENTER BARRANCA CA. CASTILLA 370, LOCAL 1 BARRANCA BARRANCA BARRANCA AV. JOSE GALVEZ 285 - BARRANCA BARRANCA BARRANCA BELLAVISTA SAN MARTIN ESQ AV SAN MARTIN C-5 Y AV. AUGUSTO B LEGUÍA C-7 BELLAVISTA BELLAVISTA C.C. EL QUINDE JR. SOR MANUELA GIL 151, LOCAL LC-323, 325, 327 CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA JR. TARAPACA 719 - 721 - CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA CAMANA - AREQUIPA JR. 28 DE JULIO 405, ESQ. CON JR. NAVARRETE CAMANA CAMANA MALA JR. REAL 305 MALA CAÑETE CAÑETE JR. DOS DE MAYO 434-438-442-444, SAN VICENTE DE PAUL DE CAÑETE SAN VICENTE DE CAÑETE CAÑETE MEGAPLAZA CAÑETE AV. MARISCAL BENAVIDES 1000-1100-1150 Y CA. MARGARITA 101, LC L-5 SAN VICENTE DE CAÑETE CAÑETE EL PEDREGAL HABILIT. URBANA CENTRO POBLADO DE SERV. BÁSICOS EL PEDREGAL MZ. G LT. 2 MAJES CAYLLOMA LA MERCED JR. TARMA 444 - LA MERCED CHANCHAMAYO CHANCHAMAYO CHICLAYO AV. -

Girolamo Muziano, Scipione Pulzone, and the First Generation of Jesuit Art

journal of jesuit studies 6 (2019) 196-212 brill.com/jjs Girolamo Muziano, Scipione Pulzone, and the First Generation of Jesuit Art John Marciari The Morgan Library & Museum, New York [email protected] Abstract While Bernini and other artists of his generation would be responsible for much of the decoration at the Chiesa del Gesù and other Jesuit churches, there was more than half a century of art commissioned by the Jesuits before Bernini came to the attention of the order. Many of the early works painted in the 1580s and 90s are no longer in the church, and some do not even survive; even a major monument like Girolamo Muzia- no’s Circumcision, the original high altarpiece, is neglected in scholarship on Jesuit art. This paper turns to the early altarpieces painted for the Gesù by Muziano and Scipione Pulzone, to discuss the pictorial and intellectual concerns that seem to have guided the painters, and also to some extent to speculate on why their works are no longer at the Gesù, and why these artists are so unfamiliar today. Keywords Jesuit art – Il Gesù – Girolamo Muziano – Scipione Pulzone – Federico Zuccaro – Counter-Reformation – Gianlorenzo Bernini Visitors to the Chiesa del Gesù in Rome, or to the recent exhibition of Jesuit art at Fairfield University,1 might naturally be led to conclude that Gianlorenzo 1 Linda Wolk-Simon, ed., The Holy Name: Art of the Gesù; Bernini and His Age, Exh. cat., Fair- field University Art Museum, Early Modern Catholicism and the Visual Arts 17 (Philadelphia: Saint Joseph’s University Press, 2018).