Twenty Seventh Annual Meeting 1991

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gordon Ramsay Uncharted

SPECIAL PROMOTION SIX DESTINATIONS ONE CHEF “This stuff deserves to sit on the best tables of the world.” – GORDON RAMSAY; CHEF, STUDENT AND EXPLORER SPECIAL PROMOTION THIS MAGAZINE WAS PRODUCED BY NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL IN PROMOTION OF THE SERIES GORDON RAMSAY: CONTENTS UNCHARTED PREMIERES SUNDAY JULY 21 10/9c FEATURE EMBARK EXPLORE WHERE IN 10THE WORLD is Gordon Ramsay cooking tonight? 18 UNCHARTED TRAVEL BITES We’ve collected travel stories and recipes LAOS inspired by Gordon’s (L to R) Yuta, Gordon culinary journey so that and Mr. Ten take you can embark on a spin on Mr. Ten’s your own. Bon appetit! souped-up ride. TRAVEL SERIES GORDON RAMSAY: ALASKA Discover 10 Secrets of UNCHARTED Glacial ice harvester Machu Picchu In his new series, Michelle Costello Gordon Ramsay mixes a Manhattan 10 Reasons to travels to six global with Gordon using ice Visit New Zealand destinations to learn they’ve just harvested from the locals. In from Tracy Arm Fjord 4THE PATH TO Go Inside the Labyrin- New Zealand, Peru, in Alaska. UNCHARTED thine Medina of Fez Morocco, Laos, Hawaii A rare look at Gordon and Alaska, he explores Ramsay as you’ve never Road Trip: Maui the culture, traditions seen him before. and cuisine the way See the Rich Spiritual and only he can — with PHOTOS LEFT TO RIGHT: ERNESTO BENAVIDES, Cultural Traditions of Laos some heart-pumping JON KROLL, MARK JOHNSON, adventure on the side. MARK EDWARD HARRIS Discover the DESIGN BY: Best of Anchorage MARY DUNNINGTON 2 GORDON RAMSAY: UNCHARTED SPECIAL PROMOTION 3 BY JILL K. -

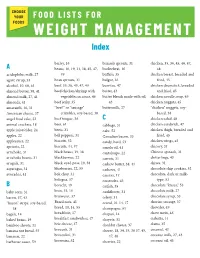

WEIGHT MANAGEMENT Index

CHOOSE YOUR FOOD LISTS FOR FOODS WEIGHT MANAGEMENT Index barley, 16 brussels sprouts, 31 chicken, 35, 36, 45, 46, 47, A beans, 10, 19, 31, 38, 45, 47, buckwheat, 16 48 acidophilus milk, 27 49 buffalo, 35 chicken breast, breaded and agave syrup, 53 bean sprouts, 31 bulgur, 16 fried, 45 alcohol, 10, 60, 61 beef, 35, 36, 45, 47, 49 burritos, 47 chicken drumstick, breaded almond butter, 38, 41 beef/chicken/shrimp with butter, 43 and fried, 45 almond milk, 27, 41 vegetables in sauce, 46 butter blends made with oil, chicken noodle soup, 49 almonds, 41 beef jerky, 35 43 chicken nuggets, 45 amaranth, 16, 31 “beef” or “sausage” buttermilk, 27 “chicken” nuggets, soy- American cheese, 37 crumbles, soy-based, 38 based, 38 angel food cake, 52 beef tongue, 36 C chicken salad, 48 animal crackers, 18 beer, 61 cabbage, 31 chicken sandwich, 47 apple juice/cider, 24 beets, 31 cake, 52 chicken thigh, breaded and apples, 22 bell peppers, 31 Canadian bacon, 35 fried, 45 applesauce, 22 biscotti, 52 candy, hard, 53 chicken wings, 45 apricots, 22 biscuits, 14, 47 canola oil, 41 chicory, 31 artichoke, 31 black beans, 19, 38 cantaloupe, 22 Chinese spinach, 31 artichoke hearts, 31 blackberries, 22 carrots, 31 chitterlings, 43 arugula, 31 black-eyed peas, 19, 38 cashew butter, 38, 41 chives, 31 asparagus, 31 blueberries, 22, 55 cashews, 41 chocolate chip cookies, 52 avocados, 41 bok choy, 31 cassava, 17 chocolate, dark or milk- bologna, 37 casseroles, 45 type, 53 B borscht, 49 catfish, 35 chocolate “kisses,” 53 baby corn, 31 bran, 15, 16 cauliflower, 31 chocolate -

Polynesian Canoe Plants, Including Breadfruit, Taro, and Coconut: the Ultimate in Sustainability Planning Posted on June 27, 2019 by Leslie Lang

HOME HOURS & DIRECTIONS GARDEN SLIDESHOW GARDEN NEWS & BLOG Polynesian Canoe Plants, Including Breadfruit, Taro, and Coconut: the Ultimate in Sustainability Planning Posted on June 27, 2019 by Leslie Lang Do you know about “canoe plants?” These are the plants—such as kalo (taro), ‘ulu (breadfruit), and niu (coconut), among others—that Polynesians brought in their carefully-stocked voyaging canoes perhaps 1,600 years ago when they first settled in Hawai‘i. Canoe plants are one more piece of the evidence showing us that the people who colonized Hawai‘i were intelligent voyagers who came in planned expeditions, not islanders who drifted here unintentionally. Not only did they successfully navigate the oceans like highways, but before they left home to explore and settle new lands, they prepared themselves well. After all, they had to sustain themselves both during their long journeys and also upon arrival in a new island group, where they didn’t know what resources they would find. They maximized their limited space by packing seeds, roots, shoots, and cuttings of their most critical plants, the ones they relied on the most for food, medicine, and for making containers, fabric, cordage, and more. We can identify about 24 plants that arrived in Hawai‘i as canoe plants. You can see samples of some of them at Hawaii Tropical Botanical Garden. The Most Significant Polynesian Canoe Plants: ‘Ulu ‘Ulu (Artocarpus altilis, Artocarpus incisus or Artocarpus communis) belongs to the Moracceae (fig or mulberry) family. Known in English as breadfruit, the ‘ulu tree produces a “fruit” that is actually a vegetable with a high carbohydrate content. -

Breadfruit, Breadnut, and Jackfruit: How Are They Related? by Fred Prescod

Comparing Breadfruit, Breadnut, and Jackfruit: How are they Related? by Fred Prescod In the first article we traced the arrival of the breadfruit plant into the New World. Now we compare breadfruit with its close relatives, breadnut and jackfruit, both also found in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. These three plants all belong to the botanical genus known as Artocarpus. The name Artocarpus is applied to about 60 different trees, all members of the fig or mulberry family (Moraceae), a botanical division which at one time included Cannabis. Trees of this genus are native to Southeast Asia and the Pacific region. The generic name (Artocarpus) is derived from the Greek words ‘artos’ (meaning bread) and ‘karpos’ (meaning fruit). The name is thought to have been established by Johann Reinhold Forster and J. Georg Adam Forster, botanists aboard the HMS Resolution on James Cook’s second voyage. In J.W. Pursglove’s publication on tropical crops, he reports that Joseph Banks, James Cook and other early travelers brought back descriptions of the breadfruit plant using phrases such as ‘bread itself is gathered as a fruit’. Breadfruit tree – Calliaqua, St. Vincent Breadfruit tree at Calliaqua, St. Vincent. [Photo by Jim Lounsberry] Unfortunately some confusion often arises from the use of common names, where a single common name may be applied to different plants in different areas. Nevertheless breadfruit itself is recognized as a seedless form of the plant known botanically as Artocarpus altilis (also Artocarpus communis), while breadnut (often also listed as Artocarpus altilis) was originally thought to be simply a race or form of the same plant with fruits containing seeds. -

Chapter 1 Definitions and Classifications for Fruit and Vegetables

Chapter 1 Definitions and classifications for fruit and vegetables In the broadest sense, the botani- Botanical and culinary cal term vegetable refers to any plant, definitions edible or not, including trees, bushes, vines and vascular plants, and Botanical definitions distinguishes plant material from ani- Broadly, the botanical term fruit refers mal material and from inorganic to the mature ovary of a plant, matter. There are two slightly different including its seeds, covering and botanical definitions for the term any closely connected tissue, without vegetable as it relates to food. any consideration of whether these According to one, a vegetable is a are edible. As related to food, the plant cultivated for its edible part(s); IT botanical term fruit refers to the edible M according to the other, a vegetable is part of a plant that consists of the the edible part(s) of a plant, such as seeds and surrounding tissues. This the stems and stalk (celery), root includes fleshy fruits (such as blue- (carrot), tuber (potato), bulb (onion), berries, cantaloupe, poach, pumpkin, leaves (spinach, lettuce), flower (globe tomato) and dry fruits, where the artichoke), fruit (apple, cucumber, ripened ovary wall becomes papery, pumpkin, strawberries, tomato) or leathery, or woody as with cereal seeds (beans, peas). The latter grains, pulses (mature beans and definition includes fruits as a subset of peas) and nuts. vegetables. Definition of fruit and vegetables applicable in epidemiological studies, Fruit and vegetables Edible plant foods excluding -

Basalt DINNER DS (English)

daily specials mixed seafood grill $35 Kauai prawn, half lobster tail, fresh catch, Hokkaido scallop, tumeric rice pilaf, tomato-chile sauce pairing Albarino | Bodegas Fefinanes, Riax Baixas, Spain glass 15 bottle 59 grilled australian lamb chops $40 Achiote spice rub, roasted fingerling potatoes, torched carrots, watercress sauce pairing Zinfandel | Hartford 'Old Vine' Russian River Valley, California glass 18 bottle 65 new york steak $39 12oz Sterling Silver Beef, Parisienne style gnocchi, baby arugula, fennel pollen, fried garlic pairing Cabernet Sauvignon | Chappellet 'Signature', Napa Valley glass 25 bottle 119 CONSUMING RAW OR UNDERCOOKED MEATS, POULTRY, SEAFOOD, SHELLFISH OR EGGS MAY INCREASE YOUR RISK OF FOODBORNE ILLNESS starters lobster bisque shot 3 bowl 6 cheese platter 13 Caramelized fennel, crème fraîche Assortment of domestic and imported cheeses, candied nuts, fresh fruit, local honey, baguette salt-n-pepper local prawns 15 charcuterie platter 14 4 quick fried local prawns, garlic confit, Duck liver pâté, salumi, cured meat, pickles, mustard, Szechuan salt-n-pepper, cilantro, negi sliced baguette charred tako 16 adobo chicken wings & crackers 13 Slow cooked octopus, eggplant, pico de gallo, arugula, Soy-vinegar glaze, garlic chili dipping sauce, and fried shallots chicken skin crackling ahi poke 13 Shoyu, green onion, furikake, togarashi, lemon zest pork belly buns 12 Charcoal bao buns, pickled vegetables, hoisin sriracha sauce basalt tiradito 15 Charred corn, micro lettuce, nori tuile, aji amarillo sauce sweet potato -

Good Things Happen When You Plant Trees

Plant a Tree … … and Good Things Happen! A guideline for younger children By Mary McLaughlin & Judy Osgood Illustrations by Edward Brooks Plant a tree and good things happen . 1. To the air we breathe 2. To the food we eat 3. To the birds that fly 4. To the animals that live on the ground 5. To the rivers, the ponds and the sea 6. To the jobs we can do 7. To the joy we have in play Teaching guide on trees. Created by Mary McLaughlin & Judy Osgood. Plant a tree and good things happen . to the air we breathe How do trees help us breathe? Key Concepts: Trees are the lungs of the earth. People need to breathe in air with oxygen to live. People breathe in oxygen (O2) and breath out carbon dioxide (CO2). Trees take in carbon dioxide and turn it into oxygen. Questions and Activities: *Put your hand on your chest. Breathe in and out. Do you feel the air coming in and going out? Where does the air come into the body and where does it exit? What organ of the body holds the air? What do we mean by bad or dirty air? *If you breathed in bad air what would happen to you? What causes bad air? What helps the air to improve? What are the other gases that make up the air that we breath? 1 Plant a tree and good things happen . to the food we eat Name some trees that give you food to eat: Brainstorm: things we eat that grow on trees: Ackee Limes Allspice Mango Almonds Maple syrup Apples Moringa Bananas Naseberry Bay leaves Olives Beechnuts Oranges Brazil nuts Pawpaw Breadfruit Peaches Cashews Persimmon Cherries Pigeon pea Chestnuts Pine nuts Cinnamon Pistachios Cloves Plums Cocoa Pomegranate Coconuts Soursop Questions and Activities Dates Starfruit *How many of these have you eaten? Gingko nuts Tamarind *Can you identify the smell and taste? Guava Walnuts *Categorize what you’ve brainstormed. -

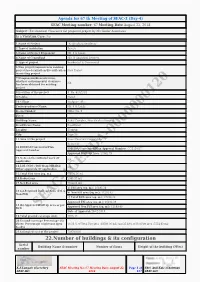

Environmental Clearance NA Has Been Obtained for Existing Project 8.Location of the Project S

Agenda for 67 th Meeting of SEAC-3 (Day-4) SEAC Meeting number: 67 Meeting Date August 22, 2018 Subject: Environment Clearance for proposed project by M/s Kedar Associates Is a Violation Case: No 1.Name of Project “Krishnakunj Residency” 2.Type of institution Private 3.Name of Project Proponent Mr. S.G. Lanke 4.Name of Consultant M/s JV Analytical Services 5.Type of project Residential & Commercial 6.New project/expansion in existing project/modernization/diversification New Project in existing project 7.If expansion/diversification, whether environmental clearance NA has been obtained for existing project 8.Location of the project S. No. 41A/2/1/1 9.Taluka Haveli 10.Village Wadgaon (Bk.) Correspondence Name: Mr. S.G. Lanke Room Number: Office No. 9 Floor: - Building Name: Rahul Complex, Near Krishna Hospital Road/Street Name: Paud Road Locality: Kothrud City: Pune-38 11.Area of the project Pune Municipal Corporation Received 12.IOD/IOA/Concession/Plan IOD/IOA/Concession/Plan Approval Number: CC/3138/17 Approval Number Approved Built-up Area: 27342.79 13.Note on the initiated work (If NA applicable) 14.LOI / NOC / IOD from MHADA/ NA Other approvals (If applicable) 15.Total Plot Area (sq. m.) 10500.00 m2 16.Deductions 2945.97 m2 17.Net Plot area 7554.03 m2 a) FSI area (sq. m.): 16193.39 18 (a).Proposed Built-up Area (FSI & b) Non FSI area (sq. m.): 11202.83 Non-FSI) c) Total BUA area (sq. m.): 27396.22 Approved FSI area (sq. m.): 16193.39 18 (b).Approved Built up area as per Approved Non FSI area (sq. -

Download PDF Menu

E N T R E E S ◊ LINGUINI CLAMS……$24.75 Manila Clams, Garlic, White Wine Sauce, Chili Flakes S E A F O O D B A R ◊ TURKEY BOLOGNESE RIGATONI……$22.50 Turkey Ragout in a Filet Tomato Sauce, Parmesan Cheese ◊ SHORT RIBS PAPPARDELLE……$26.75 ● BIG PLATTER…… $119 Wide Egg Noodles, Braised Short-Rib Ragout 9 Oysters, 9 Clams, 9 Jumbo Shrimp, Ahi Tuna Tartar, Hamachi Sashimi, 6 Peruvian ♥ PUMPKIN TORTELLINI……$24.50 Scallops Butter Squash, Jumbo Ravioli, Sage Parmesan Cream Sauce ◊ LOBSTER & CRAB LINGUINI……$35.75 Maine Lobster and Blue Crab Meat, Light Spicy Tomato Sauce ● RISOTTO MUSHROOM AND SHRIMP……$33.50 ● SMALL PLATTER…..$65 Italian Arborio Rice, Wild Mushroom, Tiger Shrimp, Parsley 6 Oysters, 6 Clams, 6 Jumbo Shrimp, Hamachi Sashimi ● SEAFOOD RISOTTO……$34.75 S T A R T E R S Italian Arborio Rice, Clams, Scallops, Calamari, Tiger Shrimp, Mussels, White SUNSET CLAM CHOWDER……$11.25 Wine Sauce Traditional New England Style WITH BACON ● OYSTERS OF THE DAY(RAW)…..½ dz $19.95 …..1 dz $38.75 CALAMARI FRITTI……$18.50 LOBSTER ROLL……$26.75 Crispy Fried Calamari, Spicy Marinara Sauce ● WILD LITTLE NECK CLAMS(RAW)…..½ dz $14.75 …..1 dz $27.95 Fresh Lobster Chunks, Diced Celery, Light Orange Mayo, Brioche Roll TURKEY MEATBALLS……$14.50 Creamy Coleslaw………Add: Fries or House Salad…$2.75 Tomato sauce, Shaved Parmegiano, Sautéed Spinach ◊ SPICY AHI TUNA TARTARE (RAW)……$19.50 FISH TACOS……$18.95 OR SHRIMP TACOS……$23.75 ● MEDITERRANEAN GRILLED OCTOPUS……$22.50 (2) Two Tacos, Marinated Cod, Cabbage, Chipotle Aioli, Cilantro, Cherry Tomato Confit, Cannellini Bean Mousse, -

The Distribution and Strategies of Plants to Grow Around Laguna Lake in Ternate

The Distribution and Strategies of Plants to Grow around Laguna Lake in Ternate Abdulrasyid Tolangara, Hasna Ahmad and Fadli Umar Biology Education Study Program, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Universitas Khairun, Indonesia Keywords: Distribution, Strategy, Plant growth, Laguna Lake. Abstract: Distribution is a spacing pattern of individuals in a population relative to one another. There are various individuals’ distribution patterns. They are commonly known as uniform, random, and clumped distribution patterns. The present research was designed as an ex post facto research which aimed to observe an existing phenomenon and recount past events to investigate factors that contributed to the occurrences. This research was conducted in an area of 7.500 m2which was dug into 50 plots of 20x20m. Random plotting method was employed to collect the data. The number of individual targeted plants which appeared in the observation plots were calculated. Each of the plants’ species was identified. The distribution patterns and the growth strategies of the individuals were determined based on the Morisita Index values. The results indicated that Laguna Lake areas were mostly surrounded by durian (Durio zibethinus L), nutmeg (Myristica fragrans Hout), breadfruit (Artocarpus communis L), and mango (Mangifera indica L.). The distribution patterns of the plants consisted of random distribution pattern (durian (Durio zibethinus L.), breadfruit (Artocarpus communis L.), and mango (Mangifera indica L.)) and clumped distribution pattern (nutmegor Myristica fragrans Hout.). In relation to plant growth strategies, the K-theory was introduced (growth strategy). Environmental factors including the soil pH, light intensity, water current, and mineral content also influenced the distribution patterns and growth strategies of the targeted plants. -

Appetizers Soups Salads Sandwiches Beverages

Crisp iceberg, bacon, red onion, egg and maytag blue. (choice of house made dressing) Salads S te a k h o u s e We d g e • 9 Crisp iceberg, bacon, red onion, egg and Point Reyes Blue. (choice of house made dressing) S t e a k h o u s e W e d g e w i t h P e t i t e F i l e t M i g n o n • 1 9 Caesar Salad • 7 House-made croutons and Reggiano parmesan (anchovies on request) Grilled Chicken Caesar • 11 Skewer of Beef Tenderloin on a Caesar • 15 Mediterranean Quinoa Bowl • 9 Spinach, romaine, quinoa, avocado, cucumbers, tomatoes, carrots, apple, feta, toasted almonds, red wine vinaigrette Add chicken breast • 5 Honey Almond Roasted Salmon & Spinach • 16 Spinach, chopped apple, pear, strawberries, onion, tomato, Beverages sweet pepper, poppy seed dressing Fresh Brewed Tea • 2.75 Lavazza Coffee • 2.75 Mancy’s Chop Salad • 10 Pepsi Fountain Products • 2.75 Romaine, shaved brussel sprouts, local bacon, heirloom tomatoes, Voss Still and Sparkling Water • 3.5 heart of palm, peas, dried cherries, fresh mozzarella and Faygo “Real Cane Sugar” Root Beer • 3 natural buttermilk dill dressing Stella Artois on Tap • 40cl • 7 Add 4 oz filet • 10 House Cabernet or Chardonnay • 6 Add chicken breast • 5 Appetizers Sandwiches C r a b S t u ff e d M u s h r o o m s • 1 0 Executive Burger • 10 Finished with mozzarella and parmesan 1/2 lb. house ground Certified Angus Beef, bakery fresh bun. -

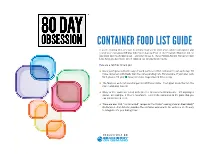

Container Food List Guide

CONTAINER FOOD LIST GUIDE If you’re reading this, it’s safe to assume that you’ve done your calorie calculations and found your individual 80 Day Obsession Eating Plan in the Program Materials list, so you know how much food to eat—and when to eat it. These Portion-Control Container Food Lists help you determine which foods to eat for your best results. Here are a few tips to help you: ● Once you figure out how many of each portion-control container to eat each day, fill those containers with foods from the corresponding lists. For example, if your plan calls for 6 greens, fill your Green Container (Vegetables) 6 times a day. ● The foods on each list are arranged by nutritional value—the higher up on the list, the more nutritional benefit! ● Many of the foods are listed with specific measurements/amounts—10 asparagus spears, for example. If there’s no amount, just fill the containers to the point that you can still fit the lid on it. ● There are over 100 “containerized” recipes on the Fixate® cooking show on Beachbody® On Demand. And Autumn provides the container equivalents for each one so it’s easy to integrate into your Eating Plan! EXCLUSIVELY ON FOOD LIST GREEN PURPLE RED YELLOW BLUE ORANGE MODIFIED REFEED CONTAINER CONTAINER CONTAINER CONTAINER CONTAINER CONTAINER SUPPLEMENTAL (Vegetables) (Fruits) (Proteins) (Carbohydrates) (Healthy Fats) (Seeds & Dressings) YELLOW S LIST • Kale, cooked or raw • Raspberries • Sardines (fresh or canned in water), • Sweet potato, chopped • Avocado, mashed or ¼ medium • Pumpkin seeds, raw Starting in Week 6, you’ll do a modified • Watercress, cooked or raw • Blueberries 7 medium or mashed, or ½ small • 12 almonds, whole, raw • Sunflower seeds, raw Refeed Day every two weeks.