Inquiry Into Homelessness in Australia Submission 52

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building an Implementation Framework for Agreements with Aboriginal Landowners: a Case Study of the Granites Mine

Building an Implementation Framework for Agreements with Aboriginal Landowners: A Case Study of The Granites Mine Rodger Donald Barnes BSc (Geol, Geog) Hons James Cook University A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Architecture Abstract This thesis addresses the important issue of implementation of agreements between Aboriginal people and mining companies. The primary aim is to contribute to developing a framework for considering implementation of agreements by examining how outcomes vary according to the processes and techniques of implementation. The research explores some of the key factors affecting the outcomes of agreements through a single case study of The Granites Agreement between Newmont Mining Corporation and traditional Aboriginal landowners made under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (NT) 1976. This is a fine-grained longitudinal study of the origins and operation of the mining agreement over a 28-year period from its inception in 1983 to 2011. A study of such depth and scope of a single mining agreement between Aboriginal people and miners has not previously been undertaken. The history of The Granites from the first European contact with Aboriginal people is compiled, which sets the study of the Agreement in the context of the continued adaption by Warlpiri people to European colonisation. The examination of the origins and negotiations of the Agreement demonstrates the way very disparate interests between Aboriginal people, government and the mining company were reconciled. A range of political agendas intersected in the course of making the Agreement which created an extremely complex and challenging environment not only for negotiations but also for managing the Agreement once it was signed. -

Critical Australian Indigenous Histories

Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah (editors) Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 16 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Transgressions [electronic resource] : critical Australian Indigenous histories / editors, Ingereth Macfarlane ; Mark Hannah. Publisher: Acton, A.C.T. : ANU E Press, 2007. ISBN: 9781921313448 (pbk.) 9781921313431 (online) Series: Aboriginal history monograph Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Indigenous peoples–Australia–History. Aboriginal Australians, Treatment of–History. Colonies in literature. Australia–Colonization–History. Australia–Historiography. Other Authors: Macfarlane, Ingereth. Hannah, Mark. Dewey Number: 994 Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Secretary/ Managing Editor), Richard Baker, Gordon Briscoe, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Christine Hansen, Luise Hercus, David Johnston, Steven Kinnane, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Ann McGrath, Frances Peters- Little, Kaye Price, Deborah Bird Rose, Peter Radoll, Tiffany Shellam Editors Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah Copy Editors Geoff Hunt and Bernadette Hince Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to Aboriginal History, Box 2837 GPO Canberra, 2601, Australia. Sales and orders for journals and monographs, and journal subscriptions: T Boekel, email: [email protected], tel or fax: +61 2 6230 7054 www.aboriginalhistory.org ANU E Press All correspondence should be addressed to: ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected], http://epress.anu.edu.au Aboriginal History Inc. -

Ready Programs and the Papulu CLC Director David Ross

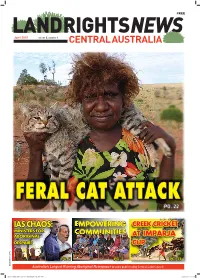

FREE April 2015 VOLUME 5. NUMBER 1. PG. ## FERAL CAT ATTACK PG. 22 IAS CHAOS: EMPOWERING CREEK CRICKET MINISTERS FOR COMMUNITIES ABORIGINAL AT IMPARJA DESPAIR? CUP PG. 2 PG. 2 PG. 33 ISSN 1839-5279 59610 CentralLandCouncil CLC Newspaper 36pp Alts1.indd 1 10/04/2015 12:32 pm NEWS Aboriginal Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion confronts an EDITORIAL angry crowd at the Alice Springs Convention Centre. Land Rights News Central He said organisations got the funding they deserved. Australia is published by the Central Land Council three times a year. The Central Land Council 27 Stuart Hwy Alice Springs NT 0870 tel: 89516211 www.clc.org.au email [email protected] Contributions are welcome SUBSCRIPTIONS Land Rights News Central Australia subscriptions are $20 per year. LRNCA is distributed free to Aboriginal organisations and communities in Central Australia Photo courtesy CAAMA To subscribe email: [email protected] IAS chaos sparks ADVERTISING Advertise in the only protests and probe newspaper to reach Aboriginal people THE AUSTRALIAN Senate will inquire original workers. Neighbouring Barkly Regional Council re- into the delayed and chaotic funding round Nearly half of the 33 organisations sur- ported 26 Aboriginal job losses as a result of in remote Central of the new Indigenous advancement scheme veyed by the Alice Springs Chamber of Com- a 35% funding cut to community services in a (IAS), which has done as much for the PM’s merce were offered less funding than they had UHJLRQWURXEOHGE\SHWUROVQLI¿QJ Australia. reputation in Aboriginal Australia as his way previously for ongoing projects. President Barb Shaw told the Tennant with words. -

Agenda Item 7.1 REPORT Report No

Agenda Item 7.1 REPORT Report No. 116/15cncl TO: ORDINARY COUNCIL – 31 AUGUST 2015 SUBJECT: MAYOR’S REPORT 1. MEETINGS AND APPOINTMENTS 1.1 Robert Sommerville; Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education, Mike Crow and Peter Solly 1.2 Alice Springs Masters Games Advisory Committee 1.3 Department of Chief Minister – Scott Lovett 1.4 Rachel and Barb Satour – Rate Payers 1.5 Clontarf - Scott Allen, Greg Buxton & Ian McAdam 1.6 CEOs, Mayors & Presidents Forum, Darwin, The Hon Bess Price, Minister for Local Government and Community Services 1.7 Northern Territory Grants Commission – Peter Thornton 1.8 Post National General Assembly Board Meeting Teleconference 1.9 Deputy Mayor Steve Brown, Cr Brendan Heenan, Cr Eli Melky 1.10 ALGA/Federal Assistance Grants Campaign Steering Committee 1.11 Western Australian Local Government Association Conference, Perth 1.12 Jimmy Cocking ALEC 1.13 Tony Tapsell CEO LGANT 1.14 Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet; Ren Kelly and Trish Johnston Acting Regional Manager 1.15 Tegan Copland - St Phillips College, School assignment 1.16 Hannah Millerick & Chloe Erlich – NT Events Photography 1.17 Alice Springs Accommodation Action Group 1.18 Road Transport Hall of Fame – Meeting re Reunion 2015 1.19 The Hon Robyn Lambley MLA 1.20 Mt Isa to Tennant Creek Pipeline Briefing – Paul Malony, APA Group 1.21 Deputy Mayor Steve Brown, Cr Eli Melky, CEO Rex Mooney 1.22 Debbie Staines - Clarity NT 1.23 Department of Chief Minister, Todd Mall Pop Up Shops 1.24 Athletics’ meeting – Mayor Damien Ryan, Deputy Mayor -

Department of the Attorney-General and Justice Page 1 of 9

ADULT CHANGE OF NAME BIRTH REGISTERED IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 1. Complete all pages of the form where appropriate and have someone over the age of 18 years witness your signature. If you do not sign your change of name application in front of a witness then it will not be registered. Original application forms must be lodged at a BDM counter or posted in. Please DO NOT FAX or EMAIL in application forms otherwise the change of name will not be processed. 2. Advertise ONCE in any newspaper published and circulating in the Northern Territory. Page Two (2) headed ‘NEWSPAPER ADVERTISEMENT ’ can be used for this purpose. Each applicant needs to organise and pay for the advertisement with the Newspaper. Once the advertisement appears in the Newspaper, remove the FULL PAGE and lodge it together with your completed change of name application form. 3. The reason for the change of name MUST BE PROVIDED . Statements like “Personal”, “I want to”, “Religion” or similar statements are NOT acceptable as reasons for applying to register a change of name. 4. Evidence of identification MUST be sighted prior to a change of name being processed . Please see page Four (4) for full identification requirements. 5. Fees: $88.00 to be paid with lodgement of forms - ($44.00 for the registration fee and $44.00 for a Birth Certificate or Change of Name Certificate). Extra birth or name change certificates are available at a cost of $44.00 each. Registered mail is $12.30 (or $16.10 for international registered mail). Clients can also collect the certificates as per addresses below. -

Northern Gas Pipeline Project ECONOMIC and SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Pty Ltd Northern Gas Pipeline Supplement to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement APPENDIX D ECONOMIC & SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Public NOVEMBER 2016 This page has been intentionally left blank Supplement to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Public— November 2016 © Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Pty Ltd Northern Gas Pipeline Project ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PUBLIC Circle Advisory Pty Ltd PO Box 5428, Albany WA 6332 ACN 161 267 250 ABN 36 161 267 250 T: +61 (0) 419 835 704 F: +61 (0) 9891 6102 E: [email protected] www.circleadvisory.com.au DOCUMENT CONTROL RECORD Document Number NGP_PL002 Project Manager James Kernaghan Author(s) Jane Munday, James Kernaghan, Martin Edwards, Fadzai Matambanadzo, Ben Garwood. Approved by Russell Brooks Approval date 8 November 2016 DOCUMENT HISTORY Version Issue Brief Description Reviewer Approver Date A 12/9/16 Report preparation by authors J Kernaghan B 6/10/16 Authors revision after first review J Kernaghan C 7/11/16 Draft sent to client for review J Kernaghan R Brooks (Jemena) 0 8/11/16 Issued M Rullo R Brooks (Jemena (Jemena) Recipients are responsible for eliminating all superseded documents in their possession. Circle Advisory Pty Ltd. ACN 161 267 250 | ABN 36 161 267 250 Address: PO Box 5428, Albany Western Australia 6332 Telephone: +61 (0) 419 835 704 Facsimile: +61 8 9891 6102 Email: [email protected] Web: www.circleadvisory.com.au Circle Advisory Pty Ltd – NGP ESIA Report 1 Preface The authors would like to acknowledge the support of a wide range of people and organisations who contributed as they could to the overall effort in assessing the potential social and economic impacts of the Northern Gas Pipeline. -

Northern Territory Safe Streets Audit

Northern Territory Safe Streets Audit Prepared by the Northern Institute at Charles Darwin University and the Australian Institute of Criminology Anthony Morgan Emma Williams Lauren Renshaw Johanna Funk Special report Northern Territory Safe Streets Audit Prepared by the Northern Institute at Charles Darwin University and the Australian Institute of Criminology Anthony Morgan Emma Williams Lauren Renshaw Johanna Funk Special report aic.gov.au © Australian Institute of Criminology 2014 ISBN 978 1 922009 72 2 (Print) 978 1 922009 73 9 (Online) Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part of this publication may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher. Published by the Australian Institute of Criminology GPO Box 2944 Canberra ACT 2601 Tel: (02) 6260 9200 Fax: (02) 6260 9299 Email: [email protected] Website: aic.gov.au Please note: minor revisions are occasionally made to publications after release. The online versions available on the AIC website will always include any revisions. Disclaimer: This research report does not necessarily reflect the policy position of the Australian Government. Edited and typeset by the Australian Institute of Criminology A full list of publications in the AIC Reports series can be found on the Australian -

Economic and Social Impact Assessment

Appendix L – Ammaroo project draft economic and social impact assessment AMMAROO PROJECT DRAFT ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT July 2017 Draft Verdant Resources Economic and Social Impact Assessment July 2017 Draft3 1 DOCUMENT and VERSION CONTROL Document number 3 Project manager Jane Munday Author Jane Munday Mary Chiang of GHD contributed to the economic and demographic sections Economic modelling by Econsearch Approved by Approval date DOCUMENT HISTORY Version Issue date Brief description Reviewer Approver 1 26 May 2017 Draft Economic and Social Elena Madden Elena Madden Impact Assessment 2 31 July 2017 Draft2 Elena Madden Elena Madden 3 17 October Draft 3 Elena Madden Elena Madden 2017 Recipients are responsible for eliminating all superseded documents in their possession True North Strategic Communication ABN 43 108 153 199 GPO Box 1261 Darwin NT 0801 Email: [email protected] Website: www.truenorthcomm.com.au 2 LIMITATIONS This Economic and Social Impact Assessment is based on desk research, the findings of a multi-disciplinary risk assessment, client input, background documents, community and stakeholder consultation and dedicated social impact assessment interviews. All requested reports were provided in a timely way and the consultant received good cooperation from the proponent in accessing information required for this report. Similarly, all organisations contacted were cooperative and there were no impediments to gathering data however there is a high level of uncertainty in sourcing and analysing both quantitative -

Double Lives : Rex Battarbee & Albert Namatjira

Double Lives Double Lives : Rex Battarbee & Albert Namatjira Martin Edmond Thesis for a Doctorate of Creative Arts The University of Western Sydney July 26, 2013 Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree in this or any other institution. signed: ……………………………………… Acknowledgments I would like to thank Nigel Roberts for the generous gift of his archive of research materials; Ivor Indyk for wise supervision; Nick Jose for intelligent readings; Gayle Quarmby for the conversations; Stephen Williamson at the Araluen Centre and Nic Brown at Flinders University Art Musuem for showing me the works; all those at Ngarrutjuta / Many Hands; Maggie Hall for her constant support. Abstract This thesis consists of a creative component which is a dual biography of the two water colour painters, Rex Battarbee and Albert Namatjira, whose relationship was to have a decisive impact on Australian art; and an exegesis which describes the process of the making of that biography in such a way as to illuminate the issues, contentious or otherwise, that may arise during the progress of a biographical inquiry. The dual biography is focussed upon the public lives of the two men, one white Australian, the other Indigenous Australian of the Arrernte people, and especially upon their professional activities as painters. It is not an exercise in psychological inquiry nor an attempt to disclose the private selves of the two artists; rather, my interest is in describing the means by which each man found his calling as an artist; the relationship, life-long, which developed between them; the times in which they lived and how this affected the courses of their lives; and the results of their work in the public sphere. -

THE NORTHERN TERRITORY PRESS from T and Gt Masthe

Stephen Hamilton and David Carment an anl n.d.: l Frc Austra, THE NORTHERN TERRITORY PRESS from t and Gt masthe. u'as ab until cl Abstract 2011:1 The history of print media in the Northern Tbtitoty is one of parish pumps and The media moguls, Cold War tensions and human rights crusades. Locally printed rrade ur and published newspapers have been pivotal to the development of a iorthern the Nor year (B. Tbrritory identity and the cultivation of the krritory's sense of dffirence from the rest of Australia. From the earliest newspapers - part news-sheet, part the time 1968: 1 government gazette - to the colourful online edition of the NT News, lfte union Territory hqs been defined by its press and has in turn defined it, in response n editorial to its remoteness and to its increasing non-Indigenous population. This article press to provides a brief overview of the Northern kruitory press, the history of which remains poorly documented. affairs't position: 'stil1 The Northern Territory has been surprisingly well served by print media since the first les: tollxspe{ successful colony was established some 140 years ago. Despite remoteness from the The main population centres of Australia and the wider world, and of its communities from -' except tb each other, small and large newspapers have repeatedly sprung up, most fleetingly, some rvith lare, with greater tenacity. The dominance of a Murdoch paper (the NT News, as it now The armr styles itself), perhaps unique among the stable in being left largely to pursue its own its suppo (albeit generally conservative) editorial line, has meant that since the mid-twentieth in Febru; century the Territory has had a loud local voice, one if of a tabloid stridency easily and the mocked by southern critics. -

UQFL102 Hilda Tuxworth Papers

FRYER LIBRARY Manuscript Finding Aid UQFL102 Hilda Tuxworth Collection Size 29 boxes, 1 parcel, 1 tube, 1 album Contents Correspondence, personal papers, newspaper cuttings, photographs, diaries of Banka Banka station (1928 to 1929, 1934 to 1936, 1941 to 1943). Collection reflects Mrs Tuxworth's interest in the local history of the Northern Territory. Biography Hilda Tuxworth, MBE, was a long term resident of Tennant Creek. She was the author of several books on the Northern Territory, particularly the Tennant Creek area. She was an interviewer for the Northern Territory Oral History Committee and a contributor to the Northern Territory Dictionary of Biography. One of her contributions was on Mary Ward, the "Missus of Banka Banka" station. Mrs Tuxworth was the mother of a former Chief Minister of the Northern Territory and MLA for Barkly, the Hon. Ian Tuxworth. "Banka Banka" cattle station, ninety miles north of Tennant Creek, was bought in 1940 by Mary and James Ward and sold to American interests in 1969. The Aboriginal employees on the station were mainly of the Warrumungu peoples. Notes Open access This collection may contain culturally sensitive words or descriptions, some of which might not normally be used in certain public or community contexts. Box 1 Davison, Patricia, The Manga-Manda Settlement, Phillip Creek: an historical reconstruction from written, oral and material evidence, parts 1 and 2, Dec 1979 Folder 1 Newell, KW, ‘Health by the people’, WHO Chronicle, Vol 29, p161-167, 1975, 10pp Hamilton, A, Socio-Cultural Factors -

One Pound Jimmy’, Escaped the ‘Stone Age’

Resisting the captured image: how Gwoja Tjungurrayi, ‘One Pound Jimmy’, escaped the ‘Stone Age’ Jillian E Barnes A cultural courtesy The language used in this story is quoted directly from tourism marketing material. These tourism images and the language used to create them are important historical records. They both reflect and help shape attitudes and aspirations. Some of these images are now considered unacceptable. My purpose is to highlight historical sensibilities. By referring to them I seek to critique rather than endorse their usage. Aboriginal readers are warned that this paper includes names and images of deceased persons. I thank Gabriel Possum and Isobel Hagan for kindly granting their permission to reproduce images of their grandfather, Gwoja Tjungurrayi. Figure 5.1: ‘Definitive’ Commonwealth stamp 1950. Design Nicholas Freeman, Freeman Design Partners. 83 Transgressions Figure 5.2: Bamboro-Kain 1839. Navy Art Gallery, Naval Historical Centre, Washington DC, [detail, image reversed]. Figure 5.3: Photograph of Gwoja Tjungurrayi 1935. Walkabout, September 1950 cover [detail]. Reproduced with permission from Tjungurrayi's granddaughters Gabriel Possum and Isobel Hagan. 84 Resisting the captured image: how Gwoja Tjungurrayi, ‘One Pound Jimmy’, escaped the ‘Stone Age’ A snapshot A chance encounter took place in the remote, rocky desert-scape east of Alice Springs sometime in the 1930s between an ambitious young tourism executive from Melbourne and a young Warlpiri-Anmatyerre man.1 The Melbourne man was touring Australia by car, searching for spectacular pictures and adventure stories for a new tourism magazine. The Aboriginal man was walking south to a large ceremonial gathering of clans with a senior companion.