Double Lives : Rex Battarbee & Albert Namatjira

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

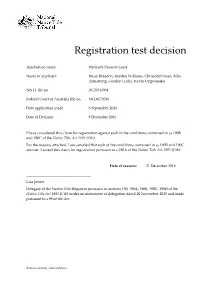

Registration Test Decision

Registration test decision Application name Henbury Pastoral Lease Name of applicant Bruce Breadon, Baydon Williams, Christobel Swan, Felix Armstrong, Gordon Lucky, Kevin Ungwanaka NNTT file no. DC2016/004 Federal Court of Australia file no. NTD47/2016 Date application made 6 September 2016 Date of Decision 9 December 2016 I have considered this claim for registration against each of the conditions contained in ss 190B and 190C of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). For the reasons attached, I am satisfied that each of the conditions contained in ss 190B and 190C are met. I accept this claim for registration pursuant to s 190A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). Date of reasons: 21 December 2016 ___________________________________ Lisa Jowett Delegate of the Native Title Registrar pursuant to sections 190, 190A, 190B, 190C, 190D of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) under an instrument of delegation dated 20 November 2015 and made pursuant to s 99 of the Act. Shared country, shared future. Reasons for decision Introduction [1] The Registrar of the Federal Court of Australia (the Court) gave a copy of the Henbury Pastoral Lease native title determination application (NTD44/2016) to the Native Title Registrar (the Registrar) on 1 September 2016 pursuant to s 63 of the Act1. This has triggered the Registrar’s duty to consider the claim made in the application for registration in accordance with s 190A: see subsection 190A(1). [2] Sections 190A(1A), (6), (6A) and (6B) set out the decisions available to the Registrar under s 190A. Subsection 190A(1A) provides for exemption from the registration test for certain amended applications and s 190A(6A) provides that the Registrar must accept a claim (in an amended application) when it meets certain conditions. -

Appendices 2011–12

Art GAllery of New South wAleS appendices 2011–12 Sponsorship 73 Philanthropy and bequests received 73 Art prizes, grants and scholarships 75 Gallery publications for sale 75 Visitor numbers 76 Exhibitions listing 77 Aged and disability access programs and services 78 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services 79 Multicultural policies and services plan 80 Electronic service delivery 81 Overseas travel 82 Collection – purchases 83 Collection – gifts 85 Collection – loans 88 Staff, volunteers and interns 94 Staff publications, presentations and related activities 96 Customer service delivery 101 Compliance reporting 101 Image details and credits 102 masterpieces from the Musée Grants received SPONSORSHIP National Picasso, Paris During 2011–12 the following funding was received: UBS Contemporary galleries program partner entity Project $ amount VisAsia Council of the Art Sponsors Gallery of New South Wales Nelson Meers foundation Barry Pearce curator emeritus project 75,000 as at 30 June 2012 Asian exhibition program partner CAf America Conservation work The flood in 44,292 the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit ANZ Principal sponsor: Archibald, Japan foundation Contemporary Asia 2,273 wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012 President’s Council TOTAL 121,565 Avant Card Support sponsor: general Members of the President’s Council as at 30 June 2012 Bank of America Merill Lynch Conservation support for The flood Steven lowy AM, Westfield PHILANTHROPY AC; Kenneth r reed; Charles in the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit Holdings, President & Denyse -

Comet and Meteorite Traditions of Aboriginal Australians

Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, 2014. Edited by Helaine Selin. Springer Netherlands, preprint. Comet and Meteorite Traditions of Aboriginal Australians Duane W. Hamacher Nura Gili Centre for Indigenous Programs, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, 2052, Australia Email: [email protected] Of the hundreds of distinct Aboriginal cultures of Australia, many have oral traditions rich in descriptions and explanations of comets, meteors, meteorites, airbursts, impact events, and impact craters. These views generally attribute these phenomena to spirits, death, and bad omens. There are also many traditions that describe the formation of meteorite craters as well as impact events that are not known to Western science. Comets Bright comets appear in the sky roughly once every five years. These celestial visitors were commonly seen as harbingers of death and disease by Aboriginal cultures of Australia. In an ordered and predictable cosmos, rare transient events were typically viewed negatively – a view shared by most cultures of the world (Hamacher & Norris, 2011). In some cases, the appearance of a comet would coincide with a battle, a disease outbreak, or a drought. The comet was then seen as the cause and attributed to the deeds of evil spirits. The Tanganekald people of South Australia (SA) believed comets were omens of sickness and death and were met with great fear. The Gunditjmara people of western Victoria (VIC) similarly believed the comet to be an omen that many people would die. In communities near Townsville, Queensland (QLD), comets represented the spirits of the dead returning home. -

At the Western Front 1918 - 2018

SALIENT CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS AT THE WESTERN FRONT 1918 - 2018 100 years on Polygon Wood 2 SALIENT CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS AT THE WESTERN FRONT New England Regional Art Museum (NERAM), Armidale 23 March – 3 June 2018 www.neram.com.au Bathurst Regional Art Gallery 10 August – 7 October 2018 www.bathurstart.com.au Anzac Memorial, Sydney October 2018 – 17 February 2019 www.anzacmemorial.nsw.gov.au Bank Art Museum Moree 5 March – 29 April 2019 DEIRDRE BEAN www.bamm.org.au HARRIE FASHER PAUL FERMAN Muswellbrook Regional Arts Centre MICHELLE HISCOCK 11 May – 30 June 2019 ROSS LAURIE www.muswellbrookartscentre.com.au STEVE LOPES EUAN MACLEOD Tweed Regional Gallery 21 November 2019 – 16 February 2020 IAN MARR artgallery.tweed.nsw.gov.au IDRIS MURPHY AMANDA PENROSE HART LUKE SCIBERRAS Opposite page: (Front row, left to right) Wendy Sharpe, Harrie Fasher, Euan Macleod, Steve Lopes, Amanda Penrose Hart George Coates, Australian official war artist’s 1916-18, 1920, oil on canvas (Middle row, left to right) Ian Marr, Deirdre Bean, Ross Laurie, Michelle Hiscock, Luke Sciberras Australian War Memorial collection WENDY SHARPE (Back row, left to right) Paul Ferman, Idris Murphy 4 Salient 5 Crosses sitting on a pillbox, Polygon Wood Pillbox, Polygon Wood 6 Salient 7 The Hon. Don Harwin Minister for the Arts, NSW Parliament Standing on top of the hill outside the village of Mont St Quentin, which Australian troops took in a decisive battle, it is impossible not to be captivated From a population of fewer than 5 million, almost 417,000 Australian men by the beauty of the landscape, but also haunted by the suffering of those enlisted to fight in the Great War, with 60,000 killed and 156,000 wounded, who experienced this bloody turning point in the war. -

Spencer Box 1 a Horn

Pitt Rivers Museum ms collections Spencer papers Box 1 A Horn correspondence Horn Letter 1 [The Adelaide Club] 17 Ap/ 94 Dear Mr. Spencer I am gradually getting things focussed here and think we can get a start on the 3d May [1] re photography I am having a small dark tent made one that can be suspended from the branch of a tree like a huge extinguisher about 4 ft in diameter I am going to take a 1/2 plate Camera with rapid rectilinear lens, and glass plates. You need not bring any rapid plates for your whole plate Camera as in the bright light up there one can get splendid instantaneous results with the Ordinary plate. Please make your Collecting plant as light as is consistent with efficiency as everything has to be carried on camels. Have you ever tried the “Tondeur” developer it is splendid for travelling as it is a one mixture solution and I find gives good results when used even a dozen times, it is a mixture of Hydrogen “Ersine” & can be had at Baker & Rouse’s I told Stirling [2] to write you to engage Keartland [3] Believe me Sincerely yrs WA Horn [4] Horn Letter 2 [The Adelaide Club] 9 June / 94 My dear Spencer, The photos of Ayers Chambers Pillar turned out fairly but a little light fogged & over exposed I got a very good one of a Tempe Downs blackfellow in the act of throwing a spear and another throwing a boomerang. if Gillen [5] has any really good [sic] you might try and get the negatives – When you are turning through the Gibber country get Harry [6] to shew you the hoards made by the ants they really seem to have moved stones by a pound in weight in order to get a clear track— I had a very rough trip by the mail it is really something to remember especially over the Gibbers and the dust was awful I hope you will be able to get Ayers rock as it would be a great addition to the book Sincerely thine [?] W A Horn Horn Letter 3 New University Club St James St. -

The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art

The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art: Arnhem Land Bark Painting, 1970-1990 By Marie Geissler The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art: Arnhem Land Bark Painting, 1970-1990 By Marie Geissler This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Marie Geissler All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5546-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5546-4 Front Cover: John Mawurndjul (Kuninjku people) Born 1952, Kubukkan near Marrkolidjban, Arnhem Land, Northern Territory Namanjwarre, saltwater crocodile 1988 Earth pigments on Stringybark (Eucalyptus tetrodonta) 206.0 x 85.0 cm (irreg) Collection Art Gallery of South Australia Maude Vizard-Wholohan Art Prize Purchase Award 1988 Accession number 8812P94 © John Mawurndjul/Copyright Agency 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................. vii Prologue ..................................................................................................... ix Theorizing contemporary Indigenous art - post 1990 Overview ................................................................................................ -

2014 Tatts Finke Desert Race

2014 TATTS FINKE DESERT RACE PARTICIPANTS DECLARATION reasonably fit for any particular purpose or might reasonably be WARNING! THIS IS AN IMPORTANT DOCUMENT WHICH AFFECTS expected to achieve any result you have made known to the YOUR LEGAL RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS, PLEASE READ IT supplier. CAREFULLY AND DO NOT SIGN IT UNLESS YOU ARE SATISFIED YOU UNDERSTAND IT. Under section 32N of the Fair Trading Act 1999, the supplier is entitled to ask you to agree that these conditions do not apply to you. If you sign this 1. WE THE UNDERSIGNED acknowledge and agree that: form, you will be agreeing that your rights to sue the supplier under the Fair Trading Act 1999 if you are killed or injured because the services DEFINITIONS were not rendered with due care and skill or they were not reasonably fit 2. In this declaration: for their purpose, are excluded, restricted or modified in the way set out in a) “Claim” means and includes any action, suit, proceeding, claim, this form. demand, damage, cost or expense however arising including but not limited to negligence but does not include a claim against a NOTE: The change to your rights, as set out in this form, does not apply if Motorcycling Organisation under any right expressly conferred by its your death or injury is due to gross negligence on the supplier's part. constitution or regulation; "Gross negligence" is defined in the Fair Trading (Recreational Services) b) “MA” means Motorcycling Australia Limited; Regulations 2004. c) “State Controlling Body” (SCB) means a state or territory motorcycling association affiliated as a member of MA; For the purposes of the clause 4, “the Supplier” shall mean and include the d) “Motorcycling Activities” means performing or participating in any Motorcycling Organisations. -

Registration Decision

Registration Decision Amended Application name Maryvale Pastoral Lease Name of applicant Desmond Jack, Reggie Kenny, Jeanette Ungwanaka and Eric Braedon on behalf of the members of the family groups with responsibility for the Imarnte, Titjikala and Idracowra estates Amended Application 25 September 2017 Received by Registrar Federal Court of Australia No. NTD35/2015 NNTT No. DC2015/005 Date of Decision 19 January 2018 Date of Reasons 25 January 2018 Decision: Claim accepted for registration I considered the claim in the Maryvale Pastoral Lease amended application for registration as required by ss 190A, 190B and 190C the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).1 I decided the claim satisfies all of the conditions required and so I must accept the claim for registration (s 190A(6)). The Register of Native Title Claims must be amended (s 190(2)(a)). __________________________ Angie Underwood Delegate of the Native Title Registrar 1 All legislative references in this decision are to the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) unless otherwise stated. Cases cited: De Rose v State of South Australia (No 2) [2005] FCAFC 110 (‘De Rose’) Gudjala People #2 v Native Title Registrar [2007] FCA 1167 (‘Gudjala (2007)’) Gudjala People No 2 v Native Title Registrar (2008) 171 FCR 317; [2008] FCAFC 157 (‘Gudjala (2008)’) Gudjala People #2 v Native Title Registrar [2009] FCA 1572(‘Gudjala (2009)’) Martin v Native Title Registrar [2001] FCA 16 (‘Martin’) Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422; [2002] HCA 58 (‘Yorta Yorta’) Mundraby v Queensland -

Journal of J. G. Macdonald on an Expedition from Port Denison to The

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

Building an Implementation Framework for Agreements with Aboriginal Landowners: a Case Study of the Granites Mine

Building an Implementation Framework for Agreements with Aboriginal Landowners: A Case Study of The Granites Mine Rodger Donald Barnes BSc (Geol, Geog) Hons James Cook University A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Architecture Abstract This thesis addresses the important issue of implementation of agreements between Aboriginal people and mining companies. The primary aim is to contribute to developing a framework for considering implementation of agreements by examining how outcomes vary according to the processes and techniques of implementation. The research explores some of the key factors affecting the outcomes of agreements through a single case study of The Granites Agreement between Newmont Mining Corporation and traditional Aboriginal landowners made under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (NT) 1976. This is a fine-grained longitudinal study of the origins and operation of the mining agreement over a 28-year period from its inception in 1983 to 2011. A study of such depth and scope of a single mining agreement between Aboriginal people and miners has not previously been undertaken. The history of The Granites from the first European contact with Aboriginal people is compiled, which sets the study of the Agreement in the context of the continued adaption by Warlpiri people to European colonisation. The examination of the origins and negotiations of the Agreement demonstrates the way very disparate interests between Aboriginal people, government and the mining company were reconciled. A range of political agendas intersected in the course of making the Agreement which created an extremely complex and challenging environment not only for negotiations but also for managing the Agreement once it was signed. -

Australian Aboriginal Verse 179 Viii Black Words White Page

Australia’s Fourth World Literature i BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Australia’s Fourth World Literature iii BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Adam Shoemaker THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS iv Black Words White Page E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Previously published by University of Queensland Press Box 42, St Lucia, Queensland 4067, Australia National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Black Words White Page Shoemaker, Adam, 1957- . Black words white page: Aboriginal literature 1929–1988. New ed. Bibliography. Includes index. ISBN 0 9751229 5 9 ISBN 0 9751229 6 7 (Online) 1. Australian literature – Aboriginal authors – History and criticism. 2. Australian literature – 20th century – History and criticism. I. Title. A820.989915 All rights reserved. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organization. All electronic versions prepared by UIN, Melbourne Cover design by Brendon McKinley with an illustration by William Sandy, Emu Dreaming at Kanpi, 1989, acrylic on canvas, 122 x 117 cm. The Australian National University Art Collection First edition © 1989 Adam Shoemaker Second edition © 1992 Adam Shoemaker This edition © 2004 Adam Shoemaker Australia’s Fourth World Literature v To Johanna Dykgraaf, for her time and care -

NEWSLETTER 1/2010 APRIL 2010 Graduating Class December 2009

NEWSLETTER 1/2010 APRIL 2010 Graduating Class December 2009 The Duntroon Society Newsletter Editor Associate Editors Dr M.J. (Mike) Ryan Colonel R.R. (Ross) Harding (Retd) School of Engineering and IT 37 QdQuandong St. UNSW@ADFA O’CONNOR ACT 2602 Australian Defence Force Academy Telephone: (02) 6248 5494 Northcott Drive E-mail: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6268 8200 Fax: (02) 6268 8443 Colonel C.A. (Chris) Field E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Cover: photographs courtesy of Defence Publishing Service AudioVisual, Duntroon (Photographers: Phillip Vavasour and Grace Costa) From the Commandant DHA Retains Harrison Road’s Brigadier M.J. Moon, DSC, AM Heritage I trust that you have all had a good break over the Christmas [Newsletter 2/2000 included an article headed Heritage and New Year period. I would like to provide the following Housing Project—Parnell Road, Duntroon. It dealt with the update on the College’s Duntroon-based activities for the skilled and meticulous major restoration of two of the five last six months or so. married quarters on Parnell Road. The work on Sinclair- You would be aware we graduated the December MacLagan House and Gwynn House was done under the Class in good shape last year. There were around 150 careful direction of the Defence Housing Authority, now graduates of all nations. They were a strong mob and should Defence Housing Australia (DHA), which manages all do well in their chosen Corps. Of course, by now, they Defence housing. In that article the Captains Cottages on should be largely on their various Regimental Officer Basic Harrison Road were listed as part of the ten or so heritage Courses around the country.