Registration Decision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Tatts Finke Desert Race

2014 TATTS FINKE DESERT RACE PARTICIPANTS DECLARATION reasonably fit for any particular purpose or might reasonably be WARNING! THIS IS AN IMPORTANT DOCUMENT WHICH AFFECTS expected to achieve any result you have made known to the YOUR LEGAL RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS, PLEASE READ IT supplier. CAREFULLY AND DO NOT SIGN IT UNLESS YOU ARE SATISFIED YOU UNDERSTAND IT. Under section 32N of the Fair Trading Act 1999, the supplier is entitled to ask you to agree that these conditions do not apply to you. If you sign this 1. WE THE UNDERSIGNED acknowledge and agree that: form, you will be agreeing that your rights to sue the supplier under the Fair Trading Act 1999 if you are killed or injured because the services DEFINITIONS were not rendered with due care and skill or they were not reasonably fit 2. In this declaration: for their purpose, are excluded, restricted or modified in the way set out in a) “Claim” means and includes any action, suit, proceeding, claim, this form. demand, damage, cost or expense however arising including but not limited to negligence but does not include a claim against a NOTE: The change to your rights, as set out in this form, does not apply if Motorcycling Organisation under any right expressly conferred by its your death or injury is due to gross negligence on the supplier's part. constitution or regulation; "Gross negligence" is defined in the Fair Trading (Recreational Services) b) “MA” means Motorcycling Australia Limited; Regulations 2004. c) “State Controlling Body” (SCB) means a state or territory motorcycling association affiliated as a member of MA; For the purposes of the clause 4, “the Supplier” shall mean and include the d) “Motorcycling Activities” means performing or participating in any Motorcycling Organisations. -

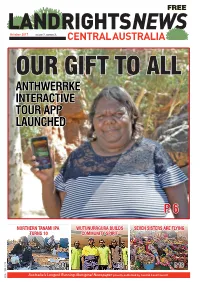

P. 6 Anthwerrke Interactive Tour App Launched

FREE October 2017 VOLUME 7. NUMBER 3. OUR GIFT TO ALL ANTHWERRKE INTERACTIVE TOUR APP LAUNCHED P. 6 NORTHERN TANAMI IPA WUTUNURRGURA BUILDS SEVEN SISTERS ARE FLYING TURNS 10 COMMUNITY SPIRIT P. 14 PG. # P. 4 PG. # P. 19 ISSN 1839-5279ISSN NEWS EDITORIAL Land Rights News Central Bush tenants need NT rental policy overhaul Australia is published by the THE TERRITORY’S Aboriginal Central Land Council three peak organisations have called times a year. on the NT Government to The Central Land Council review its rental policy in remote communities and 27 Stuart Hwy come clean on tenants’ alleged Alice Springs debts following a test case NT 0870 in the Supreme Court that tel: 89516211 highlighted rental payment chaos. www.clc.org.au At stake is whether remote email [email protected] community tenants will have Contributions are welcome to pay millions of dollars worth of rental debts. APO NT’s comments The housing department is pursuing Santa Teresa tenants over rental debts they didn’t know they owed. respond to the test case and SUBSCRIPTIONS reports since at least 2012 that several changes of landlord. half the Santa Teresa tenants that their houses be repaired, the NT Housing Department The department countersued owe an estimated $1 million in that they tell them about all Land Rights News Central has trouble working out who 70 of Santa Teresa’s 100 unpaid rent. this debt. It’s disgraceful.” Australia subscriptions are has paid what rent and when, households who took it to the When Justice Southwood With over 6000 houses $22 per year. -

Rainfall-Linked Megafires As Innate Fire Regime Elements in Arid

fevo-09-666241 July 5, 2021 Time: 15:55 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 05 July 2021 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.666241 Rainfall-Linked Megafires as Innate Fire Regime Elements in Arid Australian Spinifex (Triodia spp.) Grasslands Boyd R. Wright1,2,3*, Boris Laffineur4, Dominic Royé5, Graeme Armstrong6 and Roderick J. Fensham4,7 1 Department of Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Science, The University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia, 2 School of Agriculture and Food Science, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, QLD, Australia, 3 The Northern Territory Herbarium, Department of Land Resource Management, Alice Springs, NT, Australia, 4 Queensland Herbarium, Toowong, QLD, Australia, 5 Department of Geography, University of Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña, Spain, 6 NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, Broken Hill, NSW, Australia, 7 School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, QLD, Australia Edited by: Large, high-severity wildfires, or “megafires,” occur periodically in arid Australian spinifex Eddie John Van Etten, (Triodia spp.) grasslands after high rainfall periods that trigger fuel accumulation. Edith Cowan University, Australia Proponents of the patch-burn mosaic (PBM) hypothesis suggest that these fires Reviewed by: Ian Radford, are unprecedented in the modern era and were formerly constrained by Aboriginal Conservation and Attractions (DBCA), patch burning that kept landscape fuel levels low. This assumption deserves scrutiny, Australia as evidence from fire-prone systems globally indicates that weather factors are the Christopher Richard Dickman, The University of Sydney, Australia primary determinant behind megafire incidence, and that fuel management does not *Correspondence: mitigate such fires during periods of climatic extreme. We reviewed explorer’s diaries, Boyd R. -

Double Lives : Rex Battarbee & Albert Namatjira

Double Lives Double Lives : Rex Battarbee & Albert Namatjira Martin Edmond Thesis for a Doctorate of Creative Arts The University of Western Sydney July 26, 2013 Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree in this or any other institution. signed: ……………………………………… Acknowledgments I would like to thank Nigel Roberts for the generous gift of his archive of research materials; Ivor Indyk for wise supervision; Nick Jose for intelligent readings; Gayle Quarmby for the conversations; Stephen Williamson at the Araluen Centre and Nic Brown at Flinders University Art Musuem for showing me the works; all those at Ngarrutjuta / Many Hands; Maggie Hall for her constant support. Abstract This thesis consists of a creative component which is a dual biography of the two water colour painters, Rex Battarbee and Albert Namatjira, whose relationship was to have a decisive impact on Australian art; and an exegesis which describes the process of the making of that biography in such a way as to illuminate the issues, contentious or otherwise, that may arise during the progress of a biographical inquiry. The dual biography is focussed upon the public lives of the two men, one white Australian, the other Indigenous Australian of the Arrernte people, and especially upon their professional activities as painters. It is not an exercise in psychological inquiry nor an attempt to disclose the private selves of the two artists; rather, my interest is in describing the means by which each man found his calling as an artist; the relationship, life-long, which developed between them; the times in which they lived and how this affected the courses of their lives; and the results of their work in the public sphere. -

Western Queensland Homelands Project

PEOPLE WORKING WITH TECHNOLOGY IN REMOTE COMMUNITIES NUMBER 34 WESTERN QUEENSLAND HOMELANDS PROJECT JEANNIE LIDDLE: EDUCATOR AND CAT BOARD MEMBER RAINWATER HARVESTING POWER UP WITH E–TOOLS INVESTING IN THE OUTBACK BUSH TECHS: COOLER LIVING IN ARID AREAS • USING A MOBILE PHONE OR SATELLITE PHONE IN REMOTE AUSTRALIA NUMBER 34 ISSN: 1325–7684 Jeannie Our Place Magazine is printed on a 55% recycled paper and Liddle BUSH TECHS are printed Educator and CAT Board member. on a certified green paper. Printed by Colmans Printing using a Jeannie Liddle has a passion for chemical free plate process and vegetable Indigenous education and has worked as based inks. an Educator for many years. She is also a Centre For Appropriate Technology (CAT) 3 bushliFE Board member. JeaNNie LIDDle: EDUcatoR AND CAT boaRD MEMBER. Story by COLLEEN DANZIC 5 NEWS Our Place is published three times a eannie Liddle’s life Jeannie was born in Adelaide Grammar School. She took it all in 7 projEcTS year by the centre for Appropriate is interwoven with around the end of WWII. When her stride, believing that ‘this is just Technology, an Indigenous science and WESTERN QUEENSLAND HOMELANDS PROJECT technology organisation, which seeks to institutions that revolved she was two years old, Jeannie, her what happens to Aboriginal people’. Members of the North Queensland CAT office visit Marmanya to kick secure sustainable livelihoods through off a new project designed to provide support for looking after housing around the removal of mother, uncle and aunt returned to But she was very concerned by what appropriate technology. infrastructure and services. -

Part Ii the Question Paper

PART II THE QUESTION PAPER An index to questions appears at the end of Part II. Numerical references are to Question Paper page numbers. An asterisk preceding an entry in the index indicates that an answer has not yet been received. QUESTIONS ON NOTICE - NOT ANSWERED BY 2 JUNE 1983 NOTICE GIVEN ON DATE SHOWN From 15 March 1983 Karguru Bush Camp - Lease 795 Mr BELL to MINISTER for LANDS, INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT and TOURISM 1. Will he grant a special purposes lease to the Karguru bush camp, Tennant Creek, to enable the provision of adequate ablution faci,lities? 2. Was an applicaton for a special purposes lease for the Karguru bush camp lodged with his department in January 1982 and rejected by him in October 1982? 3. On what date did he inform the applicants of his decision to reject the application? Apprentices 800 Mr MacFARLANE to MINISTER for EDUCATION 1. Is he aware that only 5 panelbeating firms in Darwin employ apprentices? 2. Do the Territory Insurance Office and other government authorities give preference to firms employing apprentices? 3. Are corporations such as Telecom encouraged to employ and apprentice local youths in their Northern Territory operations? Aboriginal Land Claims 810 Mr MacFARLANE to CHIEF MINISTER Is it a fact that under the Aboriginal Land (Northern Territory) Act (a) water is a mineral, and (b) river banks and river beds can be claimed? Timber Creek - Land Claim 811 Mr MacFARLANE to CHIEF MINISTER 1. Is it a fact that the township of Timber Creek is under land claim? 2. If the claim is successful, will the -

True Story Exhibition Catalogue

VINCENT LINGIARI ART AWARD OUR COUNTRY – TRUE STORY VINCENT LINGIARI ART AWARD OUR COUNTRY – TRUE STORY The Vincent Lingiari Art Award David Frank, Our Future, 2016, acrylic on linen, 36cm x 51cm The Vincent Lingiari Art Award atrocious treatment of Aboriginal through which their members was established in 2016 to celebrate peoples and their campaign for could secure Aboriginal Freehold the 50th Anniversary of the historic land rights. Title to their traditional land. Wave Hill Walk Off and 40 years Today Aboriginal people own since the Aboriginal Land Rights Act After persistent struggle, lobbying almost half of the land in the (NT) 1976 was enacted by the and negotiation, the Gurindji Northern Territory. Australian Parliament. secured a lease over a small portion of their traditional lands The Vincent Lingiari Award On the 23 August 1966, Vincent for residential and cultural honours the leadership, courage Lingiari, Gurindji leader and head purposes. In 1975, Prime Minister and strength of Vincent Lingiairi stockman at Wave Hill Station led Gough Whitlam poured red dirt and all those who have fought workers and their families to walk into the hands of Vincent Lingiari for their land rights. off the cattle station in protest to symbolise the return of what has against unjust working and living always been, and always will be, conditions. The stockmen and their Aboriginal land. families relocated to Wattie Creek in a strike that was to last nine One year later, the Aboriginal Land years. The Walk Off and strike Rights Act (NT) returned Aboriginal became much more than a call for reserves and mission land in the equal rights; it soon became a fight Northern Territory to traditional for the return of Gurindji Lands. -

Key Stakeholder Perceptions of Feral Camels: Aboriginal Community Survey

54 Key stakeholder perceptions P Vaarzon-Morel Report of feral camels: 49 Aboriginal community survey 2008 Key stakeholder perceptions of feral camels: Aboriginal community survey P Vaarzon-Morel 2008 Contributing author information Enquiries should be addressed to: Petronella Vaarzon-Morel: Consulting anthropologist, PO Box 3561, Alice Springs, Northern Territory 0871, Australia. Desert Knowledge CRC Report Number 49 Information contained in this publication may be copied or reproduced for study, research, information or educational purposes, subject to inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. ISBN: 1 74158 096 X (Online copy) ISSN: 1832 6684 Citation Vaarzon-Morel P. 2008. Key stakeholder perceptions of feral camels: Aboriginal community survey. DKCRC Report 49. Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre, Alice Springs. Available at http://www.desertknowledgecrc.com. au/publications/contractresearch.html The Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre is an unincorporated joint venture with 28 partners whose mission is to develop and disseminate an understanding of sustainable living in remote desert environments, deliver enduring regional economies and livelihoods based on Desert Knowledge, and create the networks to market this knowledge in other desert lands. For additional information please contact Desert Knowledge CRC Publications Officer PO Box 3971 Alice Springs NT 0871 Australia Telephone +61 8 8959 6000 Fax +61 8 8959 6048 www.desertknowledgecrc.com.au © Desert Knowledge CRC 2008 The project was funded by Australian -

November 2011

November 2011 Alice Springs Field Naturalists Club Newsletter Photo by Barb Gilfedder This pretty sedge, Cyperus vaginatus Meetings are held on the second Wednesday of each month was growing in a small creek in Alice (except December & January) at 7:00 PM at Higher Education Valley. Building at Charles Darwin University. Visitors are welcome CONTENTS Meetings, Trips and Activities...p2 Climate Change Talk...p3 Postal Address: P.O. Box 8663 Alice Valley Trip…p5 Alice Valley Birds…p7 Alice Springs, Northern Territory Ellery Creek Geology trip…p7 Ellery Creek Big Hole Birds….p9 0871 Sue’s Visitor…p9 Web site : http://www.alicefieldnaturalists.org.au 1 NEXT NEWSLETTER The deadline for the next newsletter is Friday 18 November 2011 . This year we have an extra edition . Please send your contributions to Rhondda Tomlinson – [email protected] MEETINGS . Wed 9 Nov ASFNC - Meeting, 7:00pm at the lecture theatre in the Higher Education Building at Charles Darwin University. Speaker: Anthony Molyneux “Two good seasons – Camel Treks to Eyre Creek (2009) and Ethabuka Reserve (2011)” Wed 2 Nov APS – Members’ night. Jenny Purdie - pictures from a Beddome Ranges trip, Connie Spencer - plants of eastern Canada, Barb Gilfedder - pictures from a Kimberley trip, plus other members may bring photos. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- FIELD TRIPS / ACTIVITIES. Sun 6 Nov ASFNC – Trip to Annas Reservoir. It is located 160kms from Alice Springs and is a pretty place with historical interest too. 4WD recommended. We have permission from Gary Dann of Aileron Station. Meet at Sargent Street sign on north Stuart Highway at 7.00am. to avoid the worst of the heat. -

Found Poetry As Literary Cartography: Mapping Australia with Prose Poems

Joseph Literary cartography University of Technology Sydney Sue Joseph Found poetry as literary cartography: Mapping Australia with prose poems Abstract: Found poetry is lyrical collage, with rules. Borrowing from other writers – from different writings, artefacts, sources – it must always attribute and reference accurately. This paper is derived from the beginnings of a research project into Australian legacy newspaper stories and found poetry as prose poetry, explaining the rationale behind the bigger project. Ethnographic in texture at its edges, the research project sets out to create poetic renditions of regional news of the day, circumnavigating the continent. My aim is to produce a cadenced and lyrical nonfiction transcript of Australian life, inspired by and appropriated from regional legacy media, while it still exists. The beginning of the research was a recce journey to the centre of Australia in 2016. Currently, the outcomes of the recce are six poems, five of which are nonfiction prose poems. Contextualising found poetry within the prose poetry genre – a long debated and hybrid space – the theoretical elements of this paper underpin its creative offerings. Biographical note: Dr Sue Joseph has been a journalist for more than thirty five years, working in Australia and the UK. She began working as an academic, teaching print journalism at the University of Technology Sydney in 1997. As a Senior Lecturer, she now teaches journalism and creative writing, particularly creative nonfiction writing, in both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. Her research interests are around sexuality, secrets and confession, framed by the media; ethics and trauma narrative; memoir; reflective professional practice; ethical HDR supervision; and Australian creative nonfiction. -

Chapter 5 Stakeholder Engagement and Consultation

#HPEϱ ^ƚĂŬĞŚŽůĚĞƌŶŐĂŐĞŵĞŶƚ ĂŶĚŽŶƐƵůƚĂƚŝŽŶ This page has been left intentionally blank The proposed Chandler Facility – Draft Environmental Impact Statement Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... ii 5 Stakeholder Engagement And Consultation ........................................................................... 5-1 5.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 5-1 5.2 Regulatory requirements ......................................................................................... 5-1 5.3 Consultation objectives ........................................................................................... 5-1 5.4 Consultation methodology ...................................................................................... 5-2 5.5 Consultation activities undertaken .......................................................................... 5-3 5.6 Key issues raised during stakeholder consultation ................................................. 5-11 5.7 Ongoing consultation (next steps) ......................................................................... 5-24 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 5-1 A breakdown of the top ten issues raised during the preparation of the Chandler EIS ... 5-2 LIST OF TABLES Table 5-1 Summary of stakeholder consultation and engagement activities ................................... 5-4 Table 5-2 Stakeholders consulted and type -

DLRM Spatial Data FTP Links

List of links to download free spatial data bundles For further details about the data and information that is managed by this department, view the 2016 Product Catalogue (download via the Northern Territory Library). Introduction Spatial data bundles are available for free download from the FTP (file transfer protocol) server. Users can search for data by browsing the server or by using direct download links provided in this document. Each zipped bundle contains spatial data in an ESRI format (GDB and shapefiles), auxiliary data where relevant (for example LUT tables), metadata link, and available maps and reports in a pdf format. To access the FTP server directly: Address https://ftp-dlrm.nt.gov.au/ Account dlrmguest Password darwin Do not use “Remember me” option if you are on shared or public computer. Free data is stored in the folder outgoing / FREE_DLRM_DATA Files are named using the following conventions: Survey group prefix eg: LandSystems, LandUnits Survey ID 4-5 character survey code Survey scale eg: 15 = data scale 1:15 000 250 = data scale 1:250 000 We recommend that users download Northern Territory survey boundary compilations (survey extents) of natural resource datasets to review available information. There are 3 NT compilations; relating to LAND, VEGETATION and WATER resource surveys. Each boundary polygon contains 18 attributes describing a resource survey dataset and includes web links to the survey metadata, reports and download zip files. The compilation datasets are updated when a new dataset is completed or an existing dataset is amended. These NT compilations can be downloaded via links in the OVERVIEW section in this document.