Some Aspects of the Hindu-Muslim Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication the Hindu Date 24 June 2009 Edition Visakhapatnam Headline Concern Over Maternal, Infant Mortality Rate

NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The Hindu Date 24 June 2009 Edition Visakhapatnam Headline Concern over maternal, infant mortality rate NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The New Indian Express Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Minister assures adequate supply of medicines NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication Dharitri Date 23 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Engagement NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication Dharitri Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Objective should be not to reduce maternal deaths, but stop it NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The Samaya Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline We are not able to utilise Centre and World Bank funds: Prasanna Acharys NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The Pragativadi Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline 67% maternal deaths occur in KBK region NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The Anupam Bharat Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Free medicines to be given to pregnant women: Minister Ghadei NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The Odisha Bhaskar Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Deliver Now for Women+Children campaign NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication Khabar Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Government hospitals not to give prescriptions for delivery cases NEWS CLIPPING Client -

Chapter 9. the Programme and Achievements of the Early Nationalist

Chapter 9. The Programme and Achievements of the Early Nationalist Very Short Questions Question 1: Name the sections into which the Congress was divided from its very inception. Answer: The Moderates and the Assertives. Question 2: During which period did the Moderates dominate the Congress? Answer: The Moderates dominated the Congress from 1885 to 1905. Question 3: Name any three important leaders of the Moderates. Or Name two leaders of the Moderates. Answer: The three important leaders of the moderates were: (i) Dadabhai Naoroji (ii) Surendra Nath Banerjee (iii) Gopal Krishna Gokhale. Question 4: What were the early nationalists called? Answer: They were called the ‘Moderates’. Question 5: Why were the early nationalists called ‘Moderates’? Answer: The early nationalists had full faith in the sense of justice of the British. For this reason their demands as well as there methods help them in winning the title of ‘Moderates’. Question 6: Who were the Moderates ? Answer: They were the early nationalists, who believed that the British always show a sense of justice in all spheres of their Government. Question 7: State any two demands of the Moderates in respect of economic reforms. Answer: (i) Protection of Indian industries. (ii) Reduction of land revenue. Question 8: State any two demands of the Moderates in respect of political reforms. Answer: (i) Expansion of Legislative Councils. (ii) Separation between the Executive and the Judiciary. Question 9: Mention two demands of the Moderates in respect of administrative reforms. Answer: (i) Indianisation of Civil Services. (ii) Repeal of Arms Act. Question 10: What did the Moderates advocate in the field of civil rights? Answer: The Moderates opposed the curbs imposed on freedom of speech, press and association. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

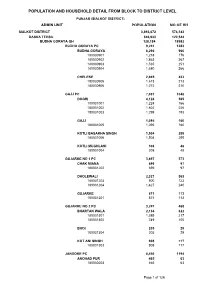

Sialkot Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH SIALKOT DISTRICT 3,893,672 574,143 DASKA TEHSIL 846,933 122,544 BUDHA GORAYA QH 128,184 18982 BUDHA GORAYA PC 9,241 1383 BUDHA GORAYA 6,296 960 180030901 1,218 176 180030902 1,863 267 180030903 1,535 251 180030904 1,680 266 CHELEKE 2,945 423 180030905 1,673 213 180030906 1,272 210 GAJJ PC 7,031 1048 DOGRI 4,124 585 180031001 1,224 166 180031002 1,602 226 180031003 1,298 193 GAJJ 1,095 160 180031005 1,095 160 KOTLI BASAKHA SINGH 1,504 255 180031006 1,504 255 KOTLI MUGHLANI 308 48 180031004 308 48 GUJARKE NO 1 PC 3,897 573 CHAK MIANA 699 97 180031202 699 97 DHOLEWALI 2,327 363 180031203 900 123 180031204 1,427 240 GUJARKE 871 113 180031201 871 113 GUJARKE NO 2 PC 3,247 468 BHARTAN WALA 2,134 322 180031301 1,385 217 180031302 749 105 BHOI 205 29 180031304 205 29 KOT ANI SINGH 908 117 180031303 908 117 JANDOKE PC 8,450 1194 ANOHAD PUR 465 63 180030203 465 63 Page 1 of 126 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JANDO KE 2,781 420 180030206 1,565 247 180030207 1,216 173 KOTLI DASO SINGH 918 127 180030204 918 127 MAHLE KE 1,922 229 180030205 1,922 229 SAKHO KE 2,364 355 180030201 1,250 184 180030202 1,114 171 KANWANLIT PC 16,644 2544 DHEDO WALI 6,974 1092 180030305 2,161 296 180030306 1,302 220 180030307 1,717 264 180030308 1,794 312 KANWAN LIT 5,856 854 180030301 2,011 290 180030302 1,128 156 180030303 1,393 207 180030304 1,324 201 KOTLI CHAMB WALI -

Indian National Congress Sessions

Indian National Congress Sessions INC sessions led the course of many national movements as well as reforms in India. Consequently, the resolutions passed in the INC sessions reflected in the political reforms brought about by the British government in India. Although the INC went through a major split in 1907, its leaders reconciled on their differences soon after to give shape to the emerging face of Independent India. Here is a list of all the Indian National Congress sessions along with important facts about them. This list will help you prepare better for SBI PO, SBI Clerk, IBPS Clerk, IBPS PO, etc. Indian National Congress Sessions During the British rule in India, the Indian National Congress (INC) became a shiny ray of hope for Indians. It instantly overshadowed all the other political associations established prior to it with its very first meeting. Gradually, Indians from all walks of life joined the INC, therefore making it the biggest political organization of its time. Most exam Boards consider the Indian National Congress Sessions extremely noteworthy. This is mainly because these sessions played a great role in laying down the foundational stone of Indian polity. Given below is the list of Indian National Congress Sessions in chronological order. Apart from the locations of various sessions, make sure you also note important facts pertaining to them. Indian National Congress Sessions Post Liberalization Era (1990-2018) Session Place Date President 1 | P a g e 84th AICC Plenary New Delhi Mar. 18-18, Shri Rahul Session 2018 Gandhi Chintan Shivir Jaipur Jan. 18-19, Smt. -

History of the Court in Avadh from 1856 A. D. up to Present Time Compiled by SRI H

History of the Court in Avadh from 1856 A. D. up to Present Time Compiled by SRI H. K. GHOSE, Bar-at-Law President, Avadh Bar Association, Lucknow BRIEF HISTORY OF OUDH Oudh was annexed to the territories of the British East India Company by Lord Dalhousie, Governor General in 1856; and twelve districts: Lucknow, Bara Banki, Faizabad, Sultanpur, Hardoi, Rae Bareli, Pratapgarh, Unnao, Gonda, Bahraich, Sitapur and Kheri were constituted into a separate Province of Oudh, under a Chief Commissioner. After some time the Civil Administration of Avadh was united under one Local Government with the districts administered by the Lt. -Governor of the NorthWestern Provinces; and the territories thus united became known as the North-Western Provinces and Oudh. Subsequently, by Act VII of 1902 passed by the Governor-General-in-Council [United Provinces (Designation) Act], the designation was changed into the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh. COURTS Ever since the said Annexation, there were separate courts to administer the laws in Oudh (Avadh) and the laws were codified by Act XVIII of 1876 (The Oudh Laws Act) passed by the Governor-General-in- Council. The Judiciary, including the highest court of appeal, was distinct from courts of the sister province of the North-Western Provinces and there were separate cadres of subordinate courts until the year 1948. JUDICIAL COMMISSIONER'S COURT After the Annexation, the highest court of appeal was established in Lucknow in 1856 with a Judicial Commissioner for the disposal of Civil and Criminal Cases. It continued to function for nearly 7 decades except for a short interregnum during the Mutiny of 1857-58. -

Surendranath Banerjee

An Illustrious Life 1 2 Surendranath Banerjee Surendranath Banerjee An Illustrious Life 3 Contents Preface vii 1. An Illustrious Life 1 Introduction • The Profile • Birth and Early Life • Beginning of the Career • Career in Education • Stint in Journalism • First Political Platform • The Demise 2. Many Faceted Personality 7 Great Man in the Making • New Career • Fighting against All Odds • Great Orator • Social and Religious Services • Message Across the Country • Uncrowned King of Bengal • Foremost in Politics • Great Reformer • Educationist and Journalist • The Unsung Hero 3. Political Journey 13 In Political Arena • Journey to Prison • Formation of Congress • President of Congress • As Legislator • Mission to England • End of Political Career 4. Political Thought 17 Traditionalist View • Ethical Politics • Faith in Human Nature • Constitutional Methods • Advocacy of Self-government • Advocacy of Liberty • Championing of National Unity • Social Reforms 4 Surendranath Banerjee • Crusade against Poverty • Negating Students’ Participation in Politics 5. Speeches at Congress Sessions 25 Presidential Address at Poona Session • Presidential Address at Ahmedabad Session • Speech at Bombay Session • Speech at Calcutta Session • Speech at Madras Session • Speech at Ahmedabad Session • Speech at Lucknow Session • Speech at Banaras Session • Speech at Lahore Session • Speech at Calcutta Session • Speech at Special Session at London 6. Addresses to the Imperial Council 145 Press Act • Separation of Judicial and Executive Functions • University and Secondary Education • Calcutta University • Decentralisation Commission • Defence of India Act • In Bengal Legislative Council 7. Lectures in England 199 Indian Press • Situation in India • Meeting in Finsbury • Debate at the Oxford Union • India and English Literature 8. Miscellaneous Speeches 243 Indian Unity • Vernacular Press Act • Appeal to the Mohammedan Community • Government and Municipalities • On Social Reforms • Swadeshism • Dacca Conference 9. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Wilson, J. E. (2016). The Temperament of Empire: Law and Conquest in Late Nineteenth Century India. In G. Cederlof, & S. Das Gupta (Eds.), Subjects, Citizens and Law: Colonial and Postcolonial India Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Subjects-Citizens-and-Law-Colonial-and-independent-India/Cederlof-Das- Gupta/p/book/9781138228443 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

The Tibetan Book of the Dead

The Tibetan Book of the Dead THE GREAT LIBERATION THROUGH HEARING IN THE BARDO BY GURU RINPOCHE ACCORDING TO KARMA LINGPA Translated with commentary by Francesca Fremantle & Chögyam Trungpa SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2010 SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com © 1975 by Francesca Fremantle and Diana Mukpo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Library of Congress catalogues the original edition of this work as follows: Karma-glin-pa, 14th cent. The Tibetan book of the dead: the great liberation through hearing in the Bardo/by Guru Rinpoche according to Karma Lingpa: a new translation with commentary by Francesca Fremantle and Chögyam Trungpa.— Berkeley: Shambhala, 1975. XX,119p.: ill.; 24 cm.—(The Clear light series) Translation of the author’s Bar do thos grol. Bibliography: p. 111–112. / Includes index. eISBN 978-0-8348-2147-7 ISBN 978-0-87773-074-3 / ISBN 978-1-57062-747-7 ISBN 978-1-59030-059-6 1. Intermediate state—Buddhism. 2. Funeral rites and ceremonies, Buddhist—Tibet. 3. Death (Buddhism). I. Fremantle, Francesca. II. Chögyam Trungpa, Trungpa Tulku, 1939–1987. III. Title. BQ4490.K3713 294.3′423 74-29615 MARC DEDICATED TO His Holiness the XVI Gyalwa Karmapa Rangjung Rigpi Dorje CONTENTS List of Illustrations Foreword, by Chögyam Trungpa, -

The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES Eurasian Center for Big History & System Forecasting SOCIAL EVOLUTION Studies in the Evolution & HISTORY of Human Societies Volume 19, Number 2 / September 2020 DOI: 10.30884/seh/2020.02.00 Contents Articles: Policarp Hortolà From Thermodynamics to Biology: A Critical Approach to ‘Intelligent Design’ Hypothesis .............................................................. 3 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin Social Evolution as an Integral Part of Universal Evolution ............. 20 Daniel Barreiros and Daniel Ribera Vainfas Cognition, Human Evolution and the Possibilities for an Ethics of Warfare and Peace ........................................................................... 47 Yelena N. Yemelyanova The Nature and Origins of War: The Social Democratic Concept ...... 68 Sylwester Wróbel, Mateusz Wajzer, and Monika Cukier-Syguła Some Remarks on the Genetic Explanations of Political Participation .......................................................................................... 98 Sarwar J. Minar and Abdul Halim The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism .......................................................... 115 Uwe Christian Plachetka Vavilov Centers or Vavilov Cultures? Evidence for the Law of Homologous Series in World System Evolution ............................... 145 Reviews and Notes: Henri J. M. Claessen Ancient Ghana Reconsidered .............................................................. 184 Congratulations -

History of Pakistan 1857-1947

Paper Code 2015 (A) ___________ gzw Number: 6101 ( , ƒgHŠk¯ ) I - ^g*0yJZ$fzÚZ HISTORY OF PAKISTAN (1857-1947) PAPER-I ª X p,6 (1857-1947) yÎ*0õg*@ TIME ALLOWED: 30 Minutes OBJECTIVE èzcz 430 = ‰Ü z MAXIMUM MARKS: 20 20 = À ½Ð à *c ™gâÃ{,]ZŠ´._Æ[Z„gŠÐ~Vz,]ZŠ‰ØŠt‚ÆwZÎCÙ ,68»!Z X÷‰ØŠ D gzZ C ÔB ÔA ]*!ZÂgeÆwZÎCÙ X^â kS XÇñY*cŠ7ðÃ~]gßÅä™:æF%N Bubbles Xǃg¦ß[Z{gÃè~]gßÅä™æF%N ™^» *c ä™æF%NÃVz,]ZŠ{Š*ciÐ-qZ X£Š Note: You have four choices for each objective type question as A, B, C and D. X,™:i/¦CÙ ]ÑZÎ,6p,6DZÎ The choice which you think is correct, fill that circle in front of that question number. Use marker or pen to fill the circles. Cutting or filling two or more circles will result in zero mark in that question. Attempt as many questions as given in objective type question paper and leave others blank. No credit will be awarded in case BUBBLES are not filled. Do not solve question on this sheet of OBJECTIVE PAPER. Q.No.1 X1 wZÎ (1) The real name of Queen of Jhansi was:- Xåx*ÝZ»ãgZ Å´Ä (1) (A) Jodha Bai ð*!JŠ (B) Lakshmi Bai ð*!$ (C) Shereen Bai ð*!,è (D) Mithi Bai ð*!¯ (2) Nadwa-tul-Ulma was established in:- XHŠHì‡! z>Z +0 (2) (A) Luckhnow ~ (B) Calcutta ® (C) Hyderabad Š*! gW© (D) Dehli ‹Š (3) The father of Shah Wali Ullah was:- Xåx*»− zZ Æ òvZà {z ÷á (3) (A) Shah Alam ݬ{÷á (B) Shah Hussain @{÷á (C) Shah Raheem ° {g ÷á (D) Shah Muhammad ·{÷á (4) The magazine Tehzeeb-ul-Akhlaq was issued by:- XH g~ YtÜÑZ$d!‚g (4) (A) Muhammad Ali Johar CÙ Z· (B) Azad Š WiZ (C) Sir Syed Ahmad Khan V{£Z¦u (D) Suleman Nadvi z~ +0yÑ (5) Muhammadan Educational Conference was established in:- Xˆ¿gŠCãÅ÷лå yZ t (5) (A) 1885 (B) 1886 (C) 1887 (D) 1888 (6) _____ is the author of "Al-Fauz-ul-Kabeer". -

Moreh-Namphalong Borders Trade

Moreh-Namphalong Borders Trade Marchang Reimeingam ISBN 978-81-7791-202-9 © 2015, Copyright Reserved The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) is engaged in interdisciplinary research in analytical and applied areas of the social sciences, encompassing diverse aspects of development. ISEC works with central, state and local governments as well as international agencies by undertaking systematic studies of resource potential, identifying factors influencing growth and examining measures for reducing poverty. The thrust areas of research include state and local economic policies, issues relating to sociological and demographic transition, environmental issues and fiscal, administrative and political decentralization and governance. It pursues fruitful contacts with other institutions and scholars devoted to social science research through collaborative research programmes, seminars, etc. The Working Paper Series provides an opportunity for ISEC faculty, visiting fellows and PhD scholars to discuss their ideas and research work before publication and to get feedback from their peer group. Papers selected for publication in the series present empirical analyses and generally deal with wider issues of public policy at a sectoral, regional or national level. These working papers undergo review but typically do not present final research results, and constitute works in progress. MOREH-NAMPHALONG BORDER TRADE Marchang Reimeingam∗ Abstract Level of border trade (BT) taking place at Moreh-Namphalong markets along Indo-Myanmar border is low but significant. BT is immensely linked with the third economies like China which actually supply goods. Moreh BT accounts to two percent of the total India-Myanmar trade. It is affected by the bandh and strikes, insurgency, unstable currency exchange rate and smuggling that led to an economic lost for traders and economy at large.