The Literature Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

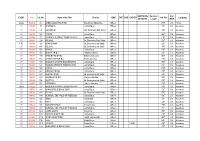

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15962-4 — The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature This fully revised second edition of The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature offers a comprehensive introduction to major writers, genres, and topics. For this edition several chapters have been completely re-written to relect major developments in Canadian literature since 2004. Surveys of ic- tion, drama, and poetry are complemented by chapters on Aboriginal writ- ing, autobiography, literary criticism, writing by women, and the emergence of urban writing. Areas of research that have expanded since the irst edition include environmental concerns and questions of sexuality which are freshly explored across several different chapters. A substantial chapter on franco- phone writing is included. Authors such as Margaret Atwood, noted for her experiments in multiple literary genres, are given full consideration, as is the work of authors who have achieved major recognition, such as Alice Munro, recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature. Eva-Marie Kröller edited the Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature (irst edn., 2004) and, with Coral Ann Howells, the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (2009). She has published widely on travel writing and cultural semiotics, and won a Killam Research Prize as well as the Distin- guished Editor Award of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals for her work as editor of the journal Canadian -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Canada's Façade of Equality: Austin Clarke's More Mary Ma

Ma, “Canada’s Façade of Equality” 11 Canada’s Façade of Equality: Austin Clarke’s More Mary Ma Canada is known as a haven for immigrants. Canadian migrants, their children, and their grandchildren live in the diaspora, a physical community who “acknowledge that ‘the old country’ […] always has some claim on their loyalty and emotions” (Cohen qtd. McLeod 237) and carry a fractured sense of identity through “living in one country but looking across time and space to another” (McLeod 237). Canada prides itself as a multicultural nation that champions inclusivity, diversity, and equality. However, it seems Canada’s often glorified multiculturalism is little more than “a media mask, […] a public advertising campaign” (McLeod 262). This façade seems to be promoted by Canadian media, government, and society to perpetuate an illusion of equality while concurrently “ignor[ing] the underlying and continuing inequalities and prejudices that blight the lives of diasporic peoples” (McLeod 262). In the novel More, Austin Clarke incisively exposes the implicit systemic and societal racism festering in Canada, while also exposing the psychological complexities of living in the diaspora. In More, Clarke unmasks Canada’s systemic discrimination which has long allowed Canadian employers to retain power while subjugating vulnerable immigrant workers. Clarke delineates this systemic racism by describing the limited employment opportunities immigrants, especially Black immigrants, have in Canada. In the novel, Bertram is an apprentice mechanic in Barbados. Upon his arrival in Canada, he earnestly pursues a job in his specialized field. However, “after two months of single-minded perusal of the pages that advertised hundreds of jobs, skilled and unskilled, that related to repairing cars” (Clarke 67), Bertram abandons his dream. -

General Studies Series

IAS General Studies Series Current Affairs (Prelims), 2013 by Abhimanu’s IAS Study Group Chandigarh © 2013 Abhimanu Visions (E) Pvt Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system or otherwise, without prior written permission of the owner/ publishers or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act, 1957. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claim for the damages. 2013 EDITION Disclaimer: Information contained in this work has been obtained by Abhimanu Visions from sources believed to be reliable. However neither Abhimanu's nor their author guarantees the accuracy and completeness of any information published herein. Though every effort has been made to avoid any error or omissions in this booklet, in spite of this error may creep in. Any mistake, error or discrepancy noted may be brought in the notice of the publisher, which shall be taken care in the next edition but neither Abhimanu's nor its authors are responsible for it. The owner/publisher reserves the rights to withdraw or amend this publication at any point of time without any notice. TABLE OF CONTENTS PERSONS IN NEWS .............................................................................................................................. 13 NATIONAL AFFAIRS .......................................................................................................................... -

Governor General's Literary Awards

Bibliothèque interculturelle 6767, chemin de la Côte-des-neiges 514.868.4720 Governor General's Literary Awards Fiction Year Winner Finalists Title Editor 2009 Kate Pullinger The Mistress of Nothing McArthur & Company Michael Crummey Galore Doubleday Canada Annabel Lyon The Golden Mean Random House Canada Alice Munro Too Much Happiness McClelland & Steward Deborah Willis Vanishing and Other Stories Penguin Group (Canada) 2008 Nino Ricci The Origins of Species Doubleday Canada Rivka Galchen Atmospheric Disturbances HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. Rawi Hage Cockroach House of Anansi Press David Adams Richards The Lost Highway Doubleday Canada Fred Stenson The Great Karoo Doubleday Canada 2007 Michael Ondaatje Divisadero McClelland & Stewart David Chariandy Soucoupant Arsenal Pulp Press Barbara Gowdy Helpless HarperCollins Publishers Heather O'Neill Lullabies for Little Criminals Harper Perennial M. G. Vassanji The Assassin's Song Doubleday Canada 2006 Peter Behrens The Law of Dreams House of Anansi Press Trevor Cole The Fearsome Particles McClelland & Stewart Bill Gaston Gargoyles House of Anansi Press Paul Glennon The Dodecahedron, or A Frame for Frames The Porcupine's Quill Rawi Hage De Niro's Game House of Anansi Press 2005 David Gilmour A Perfect Night to Go to China Thomas Allen Publishers Joseph Boyden Three Day Road Viking Canada Golda Fried Nellcott Is My Darling Coach House Books Charlotte Gill Ladykiller Thomas Allen Publishers Kathy Page Alphabet McArthur & Company GovernorGeneralAward.xls Fiction Bibliothèque interculturelle 6767, -

150 Canadian Books to Read

150 CANADIAN BOOKS TO READ Books for Adults (Fiction) 419 by Will Ferguson Generation X by Douglas Coupland A Better Man by Leah McLaren The Girl who was Saturday Night by Heather A Complicated Kindness by Miriam Toews O’Neill A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood Across The Bridge by Mavis Gallant Helpless by Barbara Gowdy Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood Home from the Vinyl Café by Stuart McLean All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews Indian Horse by Richard Wagamese And The Birds Rained Down by Jocelyne Saucier The Island Walkers by John Bemrose Anil’s Ghost by Michael Ondaatje The Jade Peony by Wayson Choy Annabel by Kathleen Winter jPod by Douglas Coupland As For Me and My House by Sinclair Ross Late Nights on Air by Elizabeth Hay The Back of the Turtle by Thomas King Lives of the Saints by Nino Ricci Barney’s Version by Mordecai Richler Love and Other Chemical Imbalances by Adam Beatrice & Virgil by Yann Martel Clark Beautiful Losers by Leonard Cohen Luck by Joan Barfoot The Best Kind of People by Zoe Whittall Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese The Best Laid Plans by Terry Fallis Mercy Among The Children by David Adams The Birth House by Ami McKay Richards The Bishop’s Man by Linden MacIntyre No Great Mischief by Alistair Macleod Black Robe by Brian Moore The Other Side of the Bridge by Mary Lawson Blackfly Season by Giles Blunt The Outlander by Gil Adamson The Book of Negroes by Lawrence Hill The Piano Man’s Daughter by Timothy Findley The Break by Katherena Vermette The Polished Hoe by Austin Clarke The Cat’s Table by Michael Ondaatje Quantum Night by Robert J. -

Indian Film Week Tydzień Kina Indyjskiego

TYDZIEń KINA INDYJSKIEGO 100-lecie kina w indiach kino kultura, warszawa 5–10 listopada 2012 INDIAN FILM WEEK 100 years of indian cinema kino kultura, warsaw 5–10 november 2012 W tym roku obchodzimy 100-lecie Kina Indyjskiego. This year we celebrate 100 years of Indian Cinema. Wraz z powstaniem pierwszego niemego filmu With the making of the first silent film ‘Raja Harish- „Raja Harishchandra” w 1913 roku, Indyjskie Kino chandra’ in 1913 , Indian Cinema embarked on an ex- wyruszyło w pasjonującą i malowniczą podróż, ilu- citing and colourful journey, reflecting a civilization strując przemianę narodu z kolonii w wolne, demokra- in transition from a colony to a free democratic re- tyczne państwo o bogatym dziedzictwie kulturowym public with a composite cultural heritage and plural- oraz wielorakich wartościach i wzorcach. istic ethos. Indyjska Kinematografia prezentuje szeroki Indian Cinema showcases a rich bouquet of lov- wachlarz postaci sympatycznych włóczęgów, ponad- able vagabonds, evergreen romantics, angry young czasowych romantyków, młodych buntowników, men, dancing queens and passionate social activists. roztańczonych królowych i żarliwych działaczy spo- Broadly defined by some as ‘cinema of interruption’, łecznych. Typowe Kino Indyjskie, zwane bollywoodz- complete with its song and dance ritual, thrills and ac- kim, przez niektórych określane szerokim mianem tion, melodrama, popular Indian cinema, ‘Bollywood’, „cinema of interruption” – kina przeplatanego pio- has endeared itself to global audiences for its enter- senką, tańcem, emocjami i akcją, teatralnością, dzięki tainment value. Aside from all the glitz and glamour walorowi rozrywkowemu, zjednało sobie widzów na of Bollywood, independent art house cinema has been całym świecie. Oprócz pełnego blichtru i przepy- a niche and has made a seminal contribution in en- chu Bollywood, niszowe niezależne kino artystyczne hancing the understanding of Indian society. -

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

SALA Abstracts 12.12.2011

SALA 2012: Performing South Asia at Home and Abroad SALA 2012 Performing South Asia at Home and Abroad The 12th Annual Conference of The South Asian Literary Association January 4-5, 2012 Hyatt Place 110 6th Avenue North (at Denny Way) Seattle, WA CONFERENCE PAPER ABSTRACTS Umme Al-wazedi, Augustana College Performing Invisibility: Muslim Comedians/Comedies Waging Peace through Humor in North America Azhar Usman, a Chicago-based stand-up comedian, begins his stand-up routine by describing how his long hair and beard are perceived in the streets: a white male from a car shouted out, “What’s up Usama?” and another shouted, “Yes, what’s going on Gandhi?” Azhar was confused— “Can I simultaneously embody the characteristics of Gandhi, a pacifist and the world’s most wanted terrorist?” The works of comedians like Azhar attempt to normalize the dominant discourse which usually focuses on the depiction of the bad Muslim who is portrayed in Hollywood movies as either an oppressive patriarch or a terrorist. This paper attempts to examine and analyze a stand-up comedy and two sitcoms respectively, by focusing on two specific questions: How do their performances construct a sense of their own identity as Canadians or as Americans? What role does the genre of ethnic comedy or humor play in creating an anti-racist discourse? Meera Ashar, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Show or Tell? Performance as Instruction in Govardhanram’s Saraswatichandra This paper argues that the use of the literary form of the novel and the idiom of Reform are impelled by a similar drive towards re-presentation and pedagogy and away from an understanding of instruction that has its roots in action-knowledge. -

For Immediate Release MIRIAM TOEWS NAMED RECIPIENT OF

For Immediate Release MIRIAM TOEWS NAMED RECIPIENT OF $10,000 HARBOURFRONT FESTIVAL PRIZE Toronto, September 22, 2016 — IFOA announced at a luncheon today that Miriam Toews is this year’s recipient of the $10,000 Harbourfront Festival Prize. Toews of her win: “I'm thrilled to be chosen as this year's recipient of the Harbourfront Festival Prize! I saw the list of writers who've previously received this prize and it is truly an honour to be counted amongst those titans, people like Alice Munro, Nicole Brossard, Helen Humphreys and Margaret Atwood. I'm so grateful to the committee and the festival. Thank you!” Miriam Toews was chosen by a jury composed of Deborah Dundas (Books Editor, Toronto Star), Carol Off (Host, CBC’s As It Happens) and Geoffrey E. Taylor (Director, IFOA) who said: "Miriam Toews has contributed so much to Canada’s literary tradition through her own work, but also through the tireless (and often unsung) support she provides others. She is an advocate for the mentally ill, she is a stalwart support to young writers, often providing a place at her home for writers to stay. She makes it to book launches —not just for the big publishing houses but also for small independent presses. At home she is truly part of the writing community. She takes that commitment and translates it abroad: she travels the world taking part in writers' retreats, book fairs, readings, and other appearances — and in doing so becomes an ambassador for Canadian writing and culture." Past recipients of the Harbourfront Festival Prize, which was established in 1984, include Avie Bennett, Dionne Brand, Austin Clarke, Margaret MacMillan, Alice Munro, Michael Ondaatje, Paul Quarrington, Seth and Jane Urquhart. -

Trends in Collecting Blogg

copies of Runaway (2004) were signed, and they are TRENDS IN COLLECTING commanding prices of US$400 or more for mint copies. The Love of a Good Woman (1998) is an older book and will become even more difficult to find in The Scotiabank Giller Prize mint, signed condition. ALTHOUGH NOT AS widely collected or hyped The most difficult Giller winner to find over as the Man Booker Prize, the Scotiabank Giller the next few years will be the most recent, Lam's Prize (formerly called the Giller Prize) should not Bloodletting and Miraculous Cures. It was initially be underestimated for either its selection of top published in the spring of 2006 in a hardcover Canadian fiction or its difficulty for modern literary edition of 5,000 copies. It was then released in trade collectors. paperback format a few months later. The hardcover In brief, the Giller Prize was founded by Jack edition has vanished from sight; the publisher has no Rabinovitch in honour of his wife, Doris Giller, who more first primings, and there aren't any copies to be rose to a respected status within the literary and found in Chapters/Indigo or on www.abebooks.com. newspaper community before her death in 1993. The real mystery is, where did they go? One ofDoris's big accomplishments was establishing Although the Giller Prize has emphasized literary a new standard for book reviews for the Monrreal heavyweights, the prize has done an excellent job of Gazette. promoting some of the younger or newer literary M.G. Vassanji won the inaugural Giller Prize talent rising up in Canada.