Migration, Refraction, and Black Masculine Performance in Austin Clarke’S the Question Pedro M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15962-4 — The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature This fully revised second edition of The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature offers a comprehensive introduction to major writers, genres, and topics. For this edition several chapters have been completely re-written to relect major developments in Canadian literature since 2004. Surveys of ic- tion, drama, and poetry are complemented by chapters on Aboriginal writ- ing, autobiography, literary criticism, writing by women, and the emergence of urban writing. Areas of research that have expanded since the irst edition include environmental concerns and questions of sexuality which are freshly explored across several different chapters. A substantial chapter on franco- phone writing is included. Authors such as Margaret Atwood, noted for her experiments in multiple literary genres, are given full consideration, as is the work of authors who have achieved major recognition, such as Alice Munro, recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature. Eva-Marie Kröller edited the Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature (irst edn., 2004) and, with Coral Ann Howells, the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (2009). She has published widely on travel writing and cultural semiotics, and won a Killam Research Prize as well as the Distin- guished Editor Award of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals for her work as editor of the journal Canadian -

Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury

1/13/2020 Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury Subscribe Past Issues Translate RS View this email in your browser Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury January 13, 2020 (Toronto, Ontario) – Elana Rabinovitch, Executive Director of the Scotiabank Giller Prize, today announced the five-member jury panel for the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize. This year marks the 27th anniversary of the Prize. The 2020 jury members are: Canadian authors David Chariandy, Eden Robinson and Mark Sakamoto (jury chair), British critic and Editor of the Culture segment of the Guardian, Claire Armitstead, and Canadian/British author and journalist, Tom Rachman. Some background on the 2020 jury: https://mailchi.mp/50144b114b18/introducing-the-2020-scotiabank-giller-prize-jury?e=a8793904cc 1/7 1/13/2020 Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury Subscribe Past Issues Translate RS Claire Armitstead is Associate Editor, Culture, at the Guardian, where she has previously acted as arts editor, literary editor and head of books. She presents the weekly Guardian books podcast and is a regular commentator on radio, and at live events across the UK and internationally. She is a trustee of English PEN. David Chariandy is a writer and critic. His first novel, Soucouyant, was nominated for 11 literary prizes, including the Governor General’s Award and the Scotiabank https://mailchi.mp/50144b114b18/introducing-the-2020-scotiabank-giller-prize-jury?e=a8793904cc 2/7 1/13/2020 Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury Brother Subscribe GillerPast Prize. His Issues second novel, , was nominated for fourteen prizes, winningTranslate RS the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, and the Toronto Book Award. -

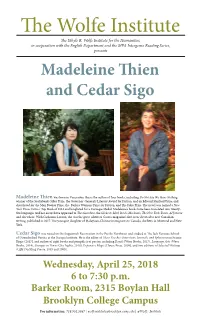

The Wolfe Institute the Ethyle R

The Wolfe Institute The Ethyle R. Wolfe Institute for the Humanities, in cooperation with the English Department and the MFA Intergenre Reading Series, presents Madeleine Thien and Cedar Sigo Madeleine Thien was born in Vancouver. She is the author of four books, including Do Not Say We Have Nothing, winner of the Scotiabank Giller Prize, the Governor-General’s Literary Award for Fiction, and an Edward Stanford Prize; and shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, and The Folio Prize. The novel was named a New York Times Critics’ Top Book of 2016 and longlisted for a Carnegie Medal. Madeleine’s books have been translated into twenty- five languages and her essays have appeared in The Guardian, the Globe & Mail, Brick, Maclean’s, The New York Times, Al Jazeera and elsewhere. With Catherine Leroux, she was the guest editor of Granta magazine’s first issue devoted to new Canadian writing, published in 2017. The youngest daughter of Malaysian-Chinese immigrants to Canada, she lives in Montreal and New York. Cedar Sigo was raised on the Suquamish Reservation in the Pacific Northwest and studied at The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute. He is the editor of There You Are: Interviews, Journals, and Ephemera on Joanne Kyger (2017), and author of eight books and pamphlets of poetry, including Royals (Wave Books, 2017), Language Arts (Wave Books, 2014), Stranger in Town (City Lights, 2010), Expensive Magic (House Press, 2008), and two editions of Selected Writings (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2003 and 2005). Wednesday, April 25, 2018 6 to 7:30 p.m. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Canada's Façade of Equality: Austin Clarke's More Mary Ma

Ma, “Canada’s Façade of Equality” 11 Canada’s Façade of Equality: Austin Clarke’s More Mary Ma Canada is known as a haven for immigrants. Canadian migrants, their children, and their grandchildren live in the diaspora, a physical community who “acknowledge that ‘the old country’ […] always has some claim on their loyalty and emotions” (Cohen qtd. McLeod 237) and carry a fractured sense of identity through “living in one country but looking across time and space to another” (McLeod 237). Canada prides itself as a multicultural nation that champions inclusivity, diversity, and equality. However, it seems Canada’s often glorified multiculturalism is little more than “a media mask, […] a public advertising campaign” (McLeod 262). This façade seems to be promoted by Canadian media, government, and society to perpetuate an illusion of equality while concurrently “ignor[ing] the underlying and continuing inequalities and prejudices that blight the lives of diasporic peoples” (McLeod 262). In the novel More, Austin Clarke incisively exposes the implicit systemic and societal racism festering in Canada, while also exposing the psychological complexities of living in the diaspora. In More, Clarke unmasks Canada’s systemic discrimination which has long allowed Canadian employers to retain power while subjugating vulnerable immigrant workers. Clarke delineates this systemic racism by describing the limited employment opportunities immigrants, especially Black immigrants, have in Canada. In the novel, Bertram is an apprentice mechanic in Barbados. Upon his arrival in Canada, he earnestly pursues a job in his specialized field. However, “after two months of single-minded perusal of the pages that advertised hundreds of jobs, skilled and unskilled, that related to repairing cars” (Clarke 67), Bertram abandons his dream. -

Fall 2013 / Winter 2014 Titles

INFLUENTIAL THINKERS INNOVATIVE IDEAS GRANTA PAYBACK THE WAYFINDERS RACE AGAINST TIME BECOMING HUMAN Margaret Atwood Wade Davis Stephen Lewis Jean Vanier Trade paperback / $18.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 ANANSIANANSIANANSI 978-0-88784-810-0 978-0-88784-842-1 978-0-88784-753-0 978-0-88784-809-4 PORTOBELLO e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 978-0-88784-872-8 978-0-88784-969-5 978-0-88784-875-9 978-0-88784-845-2 A SHORT HISTORY THE TRUTH ABOUT THE UNIVERSE THE EDUCATED OF PROGRESS STORIES WITHIN IMAGINATION FALL 2013 / Ronald Wright Thomas King Neil Turok Northrop Frye Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $14.95 978-0-88784-706-6 978-0-88784-696-0 978-1-77089-015-2 978-0-88784-598-7 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $14.95 WINTER 2014 978-0-88784-843-8 978-0-88784-895-7 978-1-77089-225-5 978-0-88784-881-0 ANANSI PUBLISHES VERY GOOD BOOKS WWW.HOUSEOFANANSI.COM Anansi_F13_cover.indd 1-2 13-05-15 11:51 AM HOUSE OF ANANSI FALL 2013 / WINTER 2014 TITLES SCOTT GRIFFIN Chair NONFICTION ... 1 SARAH MACLACHLAN President & Publisher FICTION ... 17 ALLAN IBARRA VP Finance ASTORIA (SHORT FICTION) ... 23 MATT WILLIAMS VP Publishing Operations ARACHNIDE (FRENCH TRANSLATION) ... 29 JANIE YOON Senior Editor, Nonfiction ANANSI INTERNATIONAL ... 35 JANICE ZAWERBNY Senior Editor, Canadian Fiction SPIDERLINE .. -

Governor General's Literary Awards

Bibliothèque interculturelle 6767, chemin de la Côte-des-neiges 514.868.4720 Governor General's Literary Awards Fiction Year Winner Finalists Title Editor 2009 Kate Pullinger The Mistress of Nothing McArthur & Company Michael Crummey Galore Doubleday Canada Annabel Lyon The Golden Mean Random House Canada Alice Munro Too Much Happiness McClelland & Steward Deborah Willis Vanishing and Other Stories Penguin Group (Canada) 2008 Nino Ricci The Origins of Species Doubleday Canada Rivka Galchen Atmospheric Disturbances HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. Rawi Hage Cockroach House of Anansi Press David Adams Richards The Lost Highway Doubleday Canada Fred Stenson The Great Karoo Doubleday Canada 2007 Michael Ondaatje Divisadero McClelland & Stewart David Chariandy Soucoupant Arsenal Pulp Press Barbara Gowdy Helpless HarperCollins Publishers Heather O'Neill Lullabies for Little Criminals Harper Perennial M. G. Vassanji The Assassin's Song Doubleday Canada 2006 Peter Behrens The Law of Dreams House of Anansi Press Trevor Cole The Fearsome Particles McClelland & Stewart Bill Gaston Gargoyles House of Anansi Press Paul Glennon The Dodecahedron, or A Frame for Frames The Porcupine's Quill Rawi Hage De Niro's Game House of Anansi Press 2005 David Gilmour A Perfect Night to Go to China Thomas Allen Publishers Joseph Boyden Three Day Road Viking Canada Golda Fried Nellcott Is My Darling Coach House Books Charlotte Gill Ladykiller Thomas Allen Publishers Kathy Page Alphabet McArthur & Company GovernorGeneralAward.xls Fiction Bibliothèque interculturelle 6767, -

150 Canadian Books to Read

150 CANADIAN BOOKS TO READ Books for Adults (Fiction) 419 by Will Ferguson Generation X by Douglas Coupland A Better Man by Leah McLaren The Girl who was Saturday Night by Heather A Complicated Kindness by Miriam Toews O’Neill A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood Across The Bridge by Mavis Gallant Helpless by Barbara Gowdy Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood Home from the Vinyl Café by Stuart McLean All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews Indian Horse by Richard Wagamese And The Birds Rained Down by Jocelyne Saucier The Island Walkers by John Bemrose Anil’s Ghost by Michael Ondaatje The Jade Peony by Wayson Choy Annabel by Kathleen Winter jPod by Douglas Coupland As For Me and My House by Sinclair Ross Late Nights on Air by Elizabeth Hay The Back of the Turtle by Thomas King Lives of the Saints by Nino Ricci Barney’s Version by Mordecai Richler Love and Other Chemical Imbalances by Adam Beatrice & Virgil by Yann Martel Clark Beautiful Losers by Leonard Cohen Luck by Joan Barfoot The Best Kind of People by Zoe Whittall Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese The Best Laid Plans by Terry Fallis Mercy Among The Children by David Adams The Birth House by Ami McKay Richards The Bishop’s Man by Linden MacIntyre No Great Mischief by Alistair Macleod Black Robe by Brian Moore The Other Side of the Bridge by Mary Lawson Blackfly Season by Giles Blunt The Outlander by Gil Adamson The Book of Negroes by Lawrence Hill The Piano Man’s Daughter by Timothy Findley The Break by Katherena Vermette The Polished Hoe by Austin Clarke The Cat’s Table by Michael Ondaatje Quantum Night by Robert J. -

Book Club Kit Discussion Guide Handmaid's Tale by Margaret

Book Club Kit Discussion Guide Handmaid’s Tale By Margaret Atwood Author: Margaret Atwood was born in 1939 in Ottawa, and grew up in northern Ontario and Quebec, and in Toronto. She received her undergraduate degree from Victoria College at the University of Toronto and her master’s degree from Radcliffe College. Margaret Atwood is the author of more than forty books of fiction, poetry, and critical essays. Her latest book of short stories is Stone Mattress: Nine Tales (2014). Her MaddAddam trilogy – the Giller and Booker prize- nominated Oryx and Crake (2003), The Year of the Flood (2009), and MaddAddam (2013) – is currently being adapted for HBO. The Door is her latest volume of poetry (2007). Her most recent non-fiction books are Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth (2008) and In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination (2011). Her novels include The Blind Assassin, winner of the Booker Prize; Alias Grace, which won the Giller Prize in Canada and the Premio Mondello in Italy; and The Robber Bride, Cat’s Eye, The Handmaid’s Tale – coming soon as a TV series with MGM and Hulu – and The Penelopiad. Her new novel, The Heart Goes Last, was published in September 2015. Forthcoming in 2016 are Hag-Seed, a novel revisitation of Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, for the Hogarth Shakespeare Project, and Angel Catbird – with a cat-bird superhero – a graphic novel with co-creator Johnnie Christmas. (Dark Horse.) Margaret Atwood lives in Toronto with writer Graeme Gibson. (From author’s website.) Summary: In the world of the near future, who will control women's bodies? Offred is a Handmaid in the Republic of Gilead. -

14 May IFOA Weekly Press Release

For Immediate Release IFOA WEEKLY PRESENTS BRILLIANT READINGS, STIMULATING ROUND TABLES AND CANADA’S LARGEST LITERARY EVENT FOR CHILDREN May participants include Heather O’Neill, David Adams Richards and Plum Johnson TORONTO, April 10, 2014 ---- IFOA Weekly ’s 40 th season continues next month with four exciting events: readings by acclaimed authors Shani Mootoo , Heather O’Neill and Alexi Zentner (May 7); Canada’s largest literary festival for children, Forest of Reading (May 14 –15); an evening with Canadian writers David Adams Richards , Nadia Bozak and Krista Foss (May 21) and a conversation with memoirists Plum Johnson , Lynn Thomson and Priscila Uppal (May 28). May 7 : Scotiabank Giller Prize nominee Shani Mootoo reads from her latest novel, Moving Forward Sideways like a Crab , a moving tale about the complex realities of love and family set in both the tropical landscape of Trinidad and the muted winter cityscape of Toronto. Governor General’s Literary Award finalist Heather O’Neill reads from her new book The Girl Who Was Saturday Night , an unforgettable coming-of-age story about twins, fame and heartache, set on the seedy side of Montreal's St. Laurent Boulevard. Critically acclaimed Canadian-born author Alexi Zentner shares The Lobster Kings , a novel of sibling rivalry, love lost and won, art history and the sometimes deadly adventure that is lobster fishing off the windswept Atlantic coast. May 14 –15: The Ontario Library Association’s (OLA) Forest of Reading ® and the Festival of Trees ™ is Canada’s largest literary event for children, with more than 8,000 in attendance. At this two-day awards celebration, the winners of each Forest of Reading ® category are announced and celebrated alongside young readers. -

Library Writer-In- Residence Wins Giller

2003 Operating Budget and 2003-2007 Security Guard Services – Award of Proposal Capital Budget Authority has been given to appropriate The Board approved and forwarded the Library officials to commence negotiations 2003 Operating Budget Submission to and, if successfully concluded, enter into the City for discussion and consideration. an agreement with The Inner-Tec Group The Library’s submission is prepared in for the supply of security guard services. accordance with the instructions issued by the City to all Departments, Agencies, Snow Removal Services – Award of Contract Boards and Commissions. Also approved Toronto Public Library will enter into was the 2003–2007 Capital Budget agreements with lowest bidders on snow TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY NEWS AND VIEWS VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 9 • OCTOBER 2002 including a complete summary of all removal. These are Jimrick’s Property projects. The Toronto Public Library’s Services in the east, north and south dis- Popular children's author Kenneth Oppel is 2003 portion of the capital budget is val- tricts and L. & J. Landscaping in the west. Library Writer-in- presented with the 2002 Toronto Public ued at $15.2 million gross and $12.4 mil- Library Celebrates Reading Award by lion net. Projects over the 2003–2007 Residence wins Giller Library Board Chair Gillian Mason at the period total $27.4 million gross and $23.9 Next Library Board meeting: THE PRESTIGIOUS Giller Prize was library's gala A Novel Afternoon fundrais- million net. Monday, November 25, 2002 awarded to Austin C. Clarke for his book, er, held November 3 at the Granite Club. The Polished Hoe, on November 5. -

Media Release After Hours Conversation with Marina Endicott and Jacqueline Baker: a Starfest Event

Media Release February 19, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE After Hours Conversation with Marina Endicott and Jacqueline Baker: a STARFest event St. ALBERT—Marina Endicott, local favourite and one of Canada’s most critically acclaimed and beloved storytellers, returns to STARFest with The Difference, a sweeping novel set on board a Nova Scotian merchant ship sailing through the South Pacific in 1912. Marina Endicott will be in conversation with Jacqueline Baker at this special STARFest event on Friday, March 13 at 7:00 p.m. in Forsyth Hall at the downtown St. Albert Public Library. The Difference opens with a three-masted barque from Nova Scotia sailing the trade winds to the South Pacific. On board, young Kay feels herself not wanted on her sister’s long-postponed honeymoon voyage. But Thea will not abandon her young sister, so Kay too embarks on a life-changing voyage to the other side of the world. At the heart of The Difference is a crystallizing moment in Micronesia: forming a sudden bond with a young boy from a remote island, Thea takes him away as her son. The repercussions of this act force Kay, who considers the boy her brother, to examine her own assumptions—increasingly at odds with those of society around her—about what is forgivable, and what is right. Madeleine Thien, Giller Prize-winning author of Do Not Say We Have Nothing, says this about The Difference: “Marina Endicott allows her characters to exist without being afraid of their (and our) moral dilemmas and failures, or the gap between our intentions and our understanding.