Language Subareas in Ethiopia Reconsidered1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

519 Ethiopia Report With

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Ethiopia: A New Start? T • ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY KJETIL TRONVOLL ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully © Minority Rights Group 2000 acknowledges the support of Bilance, Community Aid All rights reserved Abroad, Dan Church Aid, Government of Norway, ICCO Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- and all other organizations and individuals who gave commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- financial and other assistance for this Report. mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. For further information please contact MRG. This Report has been commissioned and is published by A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the ISBN 1 897 693 33 8 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the ISSN 0305 6252 author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in Published April 2000 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. Typset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR KJETIL TRONVOLL is a Research Fellow and Horn of Ethiopian elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1994, Africa Programme Director at the Norwegian Institute of and the Federal and Regional Assemblies in 1995. -

High Vowel Fricativization As an Areal Feature of the Northern Cameroon Grassfields

High vowel fricativization as an areal feature of the northern Cameroon Grassfields Matthew Faytak WOCAL 8, | August 23, 2015 Overview High vowel fricativization is an areal or contact feature of the northern Grassfields, which carries implications for Niger-Congo reconstructions 1. What is (not) a fricativized vowel? 2. Where are they (not)? 3. Why is this interesting? Overview High vowel fricativization is an areal or contact feature of the northern Grassfields, which carries implications for Niger-Congo reconstructions 1. What is (not) a fricativized vowel? 2. Where are they (not)? 3. Why is this interesting? Fricative vowels Vowels with a fricative-like supralaryngeal constriction, which may or may not consistently result in audible fricative noise Not intended to encompass: • Devoiced or voiceless vowels Smith (2003) • Pre-/post-aspirated vowels Helgason (2002) Mortensen (2012) • Articulatory overlap at high speech rate • Wall noise sources in high vowels Shadle (1990) Prior mention Vowels that do fit one or both of the given definitions: • Apical vowels in Chinese Lee (2005) Feng (2007) Lee-Kim (2014) • Viby-i, G¨oteborges-i, etc. in Swedish Holmberg (1976) Engstrand et al. (2000) Sch¨otzet al. (2011) • Fricative vowels in Bantoid Medjo Mv´e(1997) Connell (2007) Articulatory evidence of constriction Olson and Meynadier (2015) Articulatory evidence of constriction z v " " High vowel fricativization (HVF) Fricative vowels arise from normal high vowels /i u/, often in tandem with raising of the next-lowest vowels Faytak (2014) i u e o i -

East Sudanic ʽtreeʼ on the East Sudanic Tree

Russian State University for the Humanities Institute for Oriental and Classical Studies Center of Comparative Linguistics 10th Annual Conference on Comparative-Historical Linguistics (in memory of Sergei Starostin) George Starostin (Center for Comparative Linguistics, Institute for Oriental and Classical Studies, Russian State University for the Humanities; Laboratory of Oriental and Comparative Studies, School for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, Russian Presidential Academy) Proto-East Sudanic ʽtreeʼ on the East Sudanic tree 1 General map of Nilo-Saharan and Eastern Sudanic languages (http://www.languagesgulper.com/eng/Nilo.html) 2 «Conservative»1 lexicostatistical classification of East Sudanic with glottochronological dates (based on etymological and distributional analysis of 50-item wordlists) 1 «Conservative» implies that cognate matchings are mostly based on known phonetic correspondences or on direct consonantal class matchings between potential cognates, as opposed to a more permissive understanding of phonetic similarity («à la Greenberg»). Datings given according to Sergei Starostin's glotto- chronological formula. Tree produced by StarLing software. All wordlists compiled by G. Starostin and gradually becoming available at the Global Lexicostatistical Database (http://starling.rinet.ru/new100). 3 «Tree» in particular branches of East Sudanic2 (A) Western Nilotic Singular Plural Singular Plural Acholi yàːt -í Shilluk yɛ Dho Alur — Päri yàː Lango yàt yèn Anywa ɟ ɟ - Luo Jur Luo yen Kumam yàt yàːt-á ~ yàt-ná Belanda Bor Dop Adhola yà yèn Proto-Northern Luo *yà- *yɛ-n Proto-Southern Luo *yà- *yɛ-n Kurmuk Burun Nuer ɟiat ɟen Mayak Burun yʌn Jumjum ɟâːn ɟ - Mabaan ɟâːn- ɟân- Proto-Mabaan-Burun *ya- *yʌ-n Proto-West Nilotic *ya- *yɛ-n 2 Note: the signs - and = denote easily segmented affixes (suffixes and prefixes); italicized forms denote transparent morphological innovations by analogy. -

Complexity As L2-Difficulty : Implications for Syntactic Change

Erschienen in: Theoretical Linguistics ; 45 (2019), 3-4. - S. 183-209 https://dx.doi.org/10.1515/tl-2019-0012 Theoretical Linguistics 2019; 45(3-4): 183–209 George Walkden* and Anne Breitbarth Complexity as L2-difficulty: Implications for syntactic change https://doi.org/10.1515/tl-2019-0012 Abstract: Recent work has cast doubt on the idea that all languages are equally complex; however, the notion of syntactic complexity remains underexplored. Taking complexity to equate to difficulty of acquisition for late L2 acquirers, we propose an operationalization of syntactic complexity in terms of uninterpret- able features. Trudgill’s sociolinguistic typology predicts that sociohistorical situations involving substantial late L2 acquisition should be conducive to simplification, i.e. loss of such features. We sketch a programme for investigat- ing this prediction. In particular, we suggest that the loss of bipartite negation in the history of Low German and other languages indicates that it may be on the right track. Keywords: sociolinguistic typology, syntactic change, L2 acquisition, simplification, Interpretability Hypothesis 1 Context and big picture 1.1 Typology, complexity, and language change The traditional notion that all languages are equally complex, as expressed in Hockett (1958), has recently come under attack from a number of quarters. Notably, in his seminal work Sociolinguistic Typology, Trudgill (2011) has sug- gested that different types of sociolinguistic situation lead to differential sim- plification and complexification: for instance, long-term co-territorial language contact is predicted to lead to additive complexification, whereas short-term contact involving extensive adult second-language (L2) use is predicted to lead to simplification. -

Proposal for Ethiopic Script Root Zone LGR

Proposal for Ethiopic Script Root Zone LGR LGR Version 2 Date: 2017-05-17 Document version:5.2 Authors: Ethiopic Script Generation Panel Contents 1 General Information/ Overview/ Abstract ........................................................................................ 3 2 Script for which the LGR is proposed ................................................................................................ 3 3 Background on Script and Principal Languages Using It .................................................................... 4 3.1 Local Languages Using the Script .............................................................................................. 4 3.2 Geographic Territories of the Language or the Language Map of Ethiopia ................................ 7 4 Overall Development Process and Methodology .............................................................................. 8 4.1 Sources Consulted to Determine the Repertoire....................................................................... 8 4.2 Team Composition and Diversity .............................................................................................. 9 4.3 Analysis of Code Point Repertoire .......................................................................................... 10 4.4 Analysis of Code Point Variants .............................................................................................. 11 5 Repertoire .................................................................................................................................... -

Similative Morphemes As Purpose Clause Markers in Ethiopia and Beyond Yvonne Treis

Similative morphemes as purpose clause markers in Ethiopia and beyond Yvonne Treis To cite this version: Yvonne Treis. Similative morphemes as purpose clause markers in Ethiopia and beyond. Yvonne Treis; Martine Vanhove. Similative and Equative Constructions: A cross-linguistic perspective, 117, John Benjamins, pp.91-142, 2017, Typological Studies in Language, ISBN 9789027206985. hal-01351924 HAL Id: hal-01351924 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01351924 Submitted on 4 Aug 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Similative morphemes as purpose clause markers in Ethiopia and beyond Yvonne Treis LLACAN (CNRS, INALCO, Université Sorbonne Paris-Cité) Abstract In more than 30 languages spoken at the Horn of Africa, a similative morpheme ‘like’ or a noun ‘manner’ or ‘type’ is used as a marker of purpose clauses. The paper first elaborates on the many functions of the enclitic morpheme =g ‘manner’ in Kambaata (Highland East Cushitic), which is used, among others, as a marker of the standard in similative and equative comparison (‘like’, ‘as’), of temporal clauses of immediate anteriority (‘as soon as’), of complement clauses (‘that’) and, most notably, of purpose clauses (‘in order to’). -

Chapter 1 Lexicalization Patterns

Chapter 1 Lexicalization Patterns 1 INTRODUCTION This study addresses the systematic relations in language between mean- ing and surface expression.1 (The word ``surface'' throughout this chapter simply indicates overt linguistic forms, not any derivational theory.) Our approach to this has several aspects. First, we assume we can isolate ele- ments separately within the domain of meaning and within the domain of surface expression. These are semantic elements like `Motion', `Path', `Figure', `Ground', `Manner', and `Cause', and surface elements like verb, adposition, subordinate clause, and what we will characterize as satellite. Second, we examine which semantic elements are expressed by which surface elements. This relationship is largely not one-to-one. A combina- tion of semantic elements can be expressed by a single surface element, or a single semantic element by a combination of surface elements. Or again, semantic elements of di¨erent types can be expressed by the same type of surface element, as well as the same type by several di¨erent ones. We ®nd here a range of universal principles and typological patterns as well as forms of diachronic category shift or maintenance across the typological patterns. We do not look at every case of semantic-to-surface association, but only at ones that constitute a pervasive pattern, either within a language or across languages. Our particular concern is to understand how such patterns compare across languages. That is, for a particular semantic domain, we ask if languages exhibit a wide variety of patterns, a com- paratively small number of patterns (a typology), or a single pattern (a universal). -

Nilo-Saharan’

11 Linguistic Features and Typologies in Languages Commonly Referred to as ‘Nilo-Saharan’ Gerrit J. Dimmendaal, Colleen Ahland, Angelika Jakobi, and Constance Kutsch Lojenga 11.1 Introduction The phylum referred to today as Nilo- Saharan (occasionally also Nilosaharan) was established by Greenberg (1963). It consists of a core of language families already argued to be genetically related in his earlier classiication of African languages (Greenberg 1955:110–114), consisting of Eastern Sudanic, Central Sudanic, Kunama, and Berta, and grouped under the name Macrosudanic; this language family was renamed Chari- Nile in his 1963 contribution after a suggestion by the Africanist William Welmers. In his 1963 classiication, Greenberg hypothesized that Nilo- Saharan consists of Chari- Nile and ive other languages or language fam- ilies treated as independent units in his earlier study: Songhay (Songhai), Saharan, Maban, Fur, and Koman (Coman). Bender (1997) also included the Kadu languages in Sudan in his sur- vey of Nilo-Saharan languages; these were classiied as members of the Kordofanian branch of Niger-Kordofanian by Greenberg (1963) under the name Tumtum. Although some progress has been made in our knowledge of the Kadu languages, they remain relatively poorly studied, and there- fore they are not further discussed here, also because actual historical evi- dence for their Nilo- Saharan afiliation is rather weak. Whereas there is a core of language groups now widely assumed to belong to Nilo- Saharan as a phylum or macro- family, the genetic afiliation of families such as Koman and Songhay is also disputed (as for the Kadu languages). For this reason, these latter groups are discussed separately from what is widely considered to form the core of Nilo- Saharan, Central Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

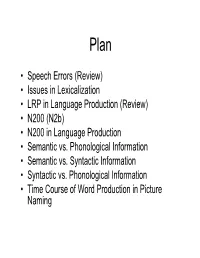

• Speech Errors (Review) • Issues in Lexicalization • LRP in Language Production (Review) • N200 (N2b) • N200 in Language Production • Semantic Vs

Plan • Speech Errors (Review) • Issues in Lexicalization • LRP in Language Production (Review) • N200 (N2b) • N200 in Language Production • Semantic vs. Phonological Information • Semantic vs. Syntactic Information • Syntactic vs. Phonological Information • Time Course of Word Production in Picture Naming Eech Sperrors • What can we learn from these things? • Anticipation Errors – a reading list Æ a leading list • Exchange Errors – fill the pool Æ fool the pill • Phonological, lexical, syntactic • Speech is planned in advance – Distance of exchange, anticipation errors suggestive of how far in advance we “plan” Word Substitutions & Word Blends • Semantic Substitutions • Lexicon is organized – That’s a horse of another color semantically AND Æ …a horse of another race phonologically • Phonological Substitutions • Word selection must happen – White Anglo-Saxon Protestant after the grammatical class of Æ …prostitute the target has been • Semantic Blends determined – Edited/annotated Æ editated – Nouns substitute for nouns; verbs for verbs • Phonological Blends – Substitutions don’t result in – Gin and tonic Æ gin and topic ungrammatical sentences • Double Blends – Arrested and prosecuted Æ arrested and persecuted Word Stem & Affix Morphemes •A New Yorker Æ A New Yorkan (American) • Seem to occur prior to lexical insertion • Morphological rules of word formation engaged during speech production Stranding Errors • Nouns & Verbs exchange, but inflectional and derivational morphemes rarely do – Rather, they are stranded • I don’t know that I’d -

The Diachronic Emergence of Retroflex Segments in Three Languages* 1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main The diachronic emergence of retroflex segments in three languages* Silke Hamann ZAS (Centre for General Linguistics), Berlin [email protected] The present study shows that though retroflex segments can be considered articulatorily marked, there are perceptual reasons why languages introduce this class into their phoneme inventory. This observation is illustrated with the diachronic developments of retroflexes in Norwegian (North- Germanic), Nyawaygi (Australian) and Minto-Nenana (Athapaskan). The developments in these three languages are modelled in a perceptually oriented phonological theory, since traditional articulatorily-based features cannot deal with such processes. 1 Introduction Cross-linguistically, retroflexes occur relatively infrequently. From the 317 languages of the UPSI database (Maddieson 1984, 1986), only 8.5 % have a voiceless retroflex stop [ˇ], 7.3 % a voiced stop [Í], 5.3 % a voiceless retroflex fricative [ß], 0.9 % a voiced fricative [¸], and 5.9 % a retroflex nasal [˜]. Compared to other segmental classes that are considered infrequent, such as a palatal nasal [¯], which occurs in 33.7 % of the UPSID languages, and the uvular stop [q], which occurs in 14.8 % of the languages, the percentages for retroflexes are strikingly low. Furthermore, typically only large segment inventories have a retroflex class, i.e. at least another coronal segment (apical or laminal) is present, as in Sanskrit, Hindi, Norwegian, Swedish, and numerous Australian Aboriginal languages. Maddieson’s (1984) database includes only one exception to this general tendency, namely the Dravidian language Kota, which has a retroflex as its only coronal fricative. -

The Ethiopian Language Policy: a Historical and Typological Overview1

Ethiopian Journal of Languages and Literature Vol. XII No. 2 June 2012 1 The Ethiopian Language Policy: A Historical and Typological Overview1 Zelealem Leyew Abstract: This paper describes the Ethiopian language policy from the historical and typological perspectives. In the historical overview, the different covert and overt language policies so far encountered are examined. A comparison is made among the language ideologies of the Imperial (1930-1974), the Derg(1974-1991) and the EPRDF (1991 – ) governments. In the typological overview, the language policies implemented by different governments are classified by type based on the existing literature on language policy. Issues surrounding language diversity, status and corpus planning and policy formulations are addressed. An attempt is made to assess and compare the Ethiopian experience with experiences of other multilingual countries. Ethiopia is not only a multilingual but also a biscriptual country in which the Ethiopic and Latin scripts are competing. Due to its historical trajectory, Ethiopia is neither Anglo-Phone nor Franco-phone in the strict sense of the terms. It promotes an endoglossic language policy with English playing an important role, but without connection to the colonial legacy. These and other complex sociolinguistic profiles make the prevalence of an optimal language policy in Ethiopia somewhat complex as compared to other Sub-Saharan African countries that promote exoglossic or mixed language policies. Key words: Language policy, Language planning, Language diversity, Linguistic human rights, Lingua-franca Assocaite Professor, Department of Linguistics, Addis Ababa University 1 I am deeply indebted to Ato Ayalew Shibeshi, Dr. Bekale Seyum and Fitsum Abate for their valuable comments on the first draft of this paper. -

Occasional Papers in the Study of Sudanese Languages No

OCCASIONAL PAPERS in the study of SUDANESE LANGUAGES No. 10 Phonology of Kakuwâ (Kakwa) Yuga Juma Onziga and Leoma Gilley......................................1 Laru Vowel Harmony Nabil Abdallah......................................................................17 Lexical and Postlexical Vowel Harmony in Fur Constance Kutsch Lojenga.....................................................35 Tennet Verb Paradigms Christine Waag and Eileen Kilpatrick....................................45 Negation Strategies in Tima Suzan Alamin........................................................................61 Number in Ama Verbs Russell Norton.......................................................................75 The Prefix /ɔ́-/ in Lumun Kinship Terms and Personal Names Heleen Smits.........................................................................95 Lumun Participant Reference in Narrative Discourse Timothy Stirtz.....................................................................115 Third Person Identification and Reference in Mündü Narrative Dorothea Jeffrey.................................................................141 OCCASIONAL PAPERS in the study of SUDANESE LANGUAGES No. 10 There are a number of institutions and individuals who are interested in research on languages in Sudan and there is a need to make research presently being done available to others. The purpose of these Occasional Papers is to serve as an outlet for work papers and other useful data which might otherwise remain in private files. We hope that Sudanese and