An Interview with Barney Rosset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall2011.Pdf

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta Fall 201 1 NOW AVAILABLE Complete and updated coverage by The New York Times about WikiLeaks and their controversial release of diplomatic cables and war logs OPEN SECRETS WikiLeaks, War, and American Diplomacy The New York Times Introduction by Bill Keller • Essential, unparalleled coverage A New York Times Best Seller from the expert writers at The New York Times on the hundreds he controversial antisecrecy organization WikiLeaks, led by Julian of thousands of confidential Assange, made headlines around the world when it released hundreds of documents revealed by WikiLeaks thousands of classified U.S. government documents in 2010. Allowed • Open Secrets also contains a T fascinating selection of original advance access, The New York Times sorted, searched, and analyzed these secret cables and war logs archives, placed them in context, and played a crucial role in breaking the WikiLeaks story. • online promotion at Open Secrets, originally published as an e-book, is the essential collection www.nytimes.com/opensecrets of the Times’s expert reporting and analysis, as well as the definitive chronicle of the documents’ release and the controversy that ensued. An introduction by Times executive editor, Bill Keller, details the paper’s cloak-and-dagger “We may look back at the war logs as relationship with a difficult source. Extended profiles of Assange and Bradley a herald of the end of America’s Manning, the Army private suspected of being his source, offer keen insight engagement in Afghanistan, just as into the main players. Collected news stories offer a broad and deep view into the Pentagon Papers are now a Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the messy challenges facing American power milestone in our slo-mo exit from in Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. -

Barney Rosset by Win Mccormack

A Conversation with Barney Rosset by Win McCormack its heyday, the most influential alternative book press in the history of American publishing. Grove—and Grove’s magazine, the Evergreen Review, launched in 1957—published, among other writers, most of the French avant-garde of the era, including Alain Robbe-Grillet, Jean Genet, and Eugene Ionesco; most of the American Beats of the fifties, including Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg; and most of the key radical political thinkers of the six- ties, including Malcolm X, Frantz Fanon, and Regis Debray. He pub- lished Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot after it had been scorned by more mainstream publishers—and sold two million copies of it in the bargain. He made a specialty of Japanese literature, and intro- duced the future Nobel Prize winner Kenzaburo Oe to an American public. He published the first unexpurgated edition of D. H. Law- A CONVERSATION WITH rence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the first edition of Henry Miller’s BARNEY ROSSET Tropic of Cancer in America, partly to deliberately provoke the censors. Through his legal victories in the resulting obscenity cases, as well as in one brought on by I Am Curious (Yellow), a sexually explicit Swedish Win McCormack documentary film he distributed, he was probably more responsible than any other single individual for ending the censorship of litera- ture and film in the United States. In bestowing on Barney Rosset the honorific of Commandeur dans Grove Press was sold in 1985; its backlist is now part of Grove/ l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1999, the French Ministry of Cul- Atlantic Inc. -

University of Cincinnati

! "# $ % & % ' % !" #$ !% !' &$ &""! '() ' #$ *+ ' "# ' '% $$(' ,) * !$- .*./- 0 #!1- 2 *,*- Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2010 by Wolfgang Lueckel B.A. (equivalent) in German Literature, Universität Mainz, 2003 M.A. in German Studies, University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: Sara Friedrichsmeyer, Ph.D. Committee Members: Todd Herzog, Ph.D. (second reader) Katharina Gerstenberger, Ph.D. Richard E. Schade, Ph.D. ii Abstract In my dissertation “Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture,” I investigate the portrayal of the nuclear age and its most dreaded fantasy, the nuclear apocalypse, in German fictionalizations and cultural writings. My selection contains texts of disparate natures and provenance: about fifty plays, novels, audio plays, treatises, narratives, films from 1946 to 2009. I regard these texts as a genre of their own and attempt a description of the various elements that tie them together. The fascination with the end of the world that high and popular culture have developed after 9/11 partially originated from the tradition of nuclear fiction since 1945. The Cold War has produced strong and lasting apocalyptic images in German culture that reject the traditional biblical apocalypse and that draw up a new worldview. In particular, German nuclear fiction sees the atomic apocalypse as another step towards the technical facilitation of genocide, preceded by the Jewish Holocaust with its gas chambers and ovens. -

The Making of Chicago Review: the Meteoric Years

EIRIK STEINHOFF The Making of Chicago Review: The Meteoric Years Chicago Review’s Spring 1946 inaugural issue lays out the magazine’s ambitions with admirable force: “rather than compare, condemn, or praise, the Chicago Review chooses to present a contemporary standard of good writing.” This emphasis on the contemporary comes with a sober assessment of “the problems of a cultural as well as an economic reconversion” that followed World War II, with particular reference to the consequences this instrumentalizing logic held for contemporary writing: “The emphasis in American universities has rested too heavily on the history and analysis of literature—too lightly on its creation.” Notwithstanding this confident incipit, cr was hardly an immediate success. It had to be built from scratch by student editors who had to negotiate a sometimes supportive, sometimes antagonistic relationship with cr’s host institution, the University of Chicago. The story I tell here focuses on the labors of F.N. Karmatz and Irving Rosenthal, the two editors who put cr on the map in the 1950s, albeit in different and potentially contradictory ways. Their hugely ambitious projects twice drove cr to the brink of extinction, but they also established two idiosyncratic styles of cultural engagement that continue to inform the Review’s practice into the twenty-first century. Rosenthal’s is the story that is usually told of cr’s early years: in 1957 and ’58 he and poetry editor Paul Carroll published a strong roster of emerging Beat writers, including several provocative excerpts from Naked Lunch, William S. Burroughs’s work-in-progress. -

2008 OAH Annual Meeting • New York 1

Welcome ear colleagues in history, welcome to the one-hundred-fi rst annual meeting of the Organiza- tion of American Historians in New York. Last year we met in our founding site of Minneap- Dolis-St. Paul, before that in the national capital of Washington, DC. On the present occasion wew meet in the world’s media capital, but in a very special way: this is a bridge-and-tunnel aff air, not limitedli to just the island of Manhattan. Bridges and tunnels connect the island to the larger metropolitan region. For a long time, the peoplep in Manhattan looked down on people from New Jersey and the “outer boroughs”— Brooklyn, theth Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island—who came to the island via those bridges and tunnels. Bridge- and-tunnela people were supposed to lack the sophistication and style of Manhattan people. Bridge- and-tunnela people also did the work: hard work, essential work, beautifully creative work. You will sees this work in sessions and tours extending beyond midtown Manhattan. Be sure not to miss, for example,e “From Mambo to Hip-Hop: Th e South Bronx Latin Music Tour” and the bus tour to my own Photo by Steve Miller Steve by Photo cityc of Newark, New Jersey. Not that this meeting is bridge-and-tunnel only. Th anks to the excellent, hard working program committee, chaired by Debo- rah Gray White, and the local arrangements committee, chaired by Mark Naison and Irma Watkins-Owens, you can chose from an abundance of off erings in and on historic Manhattan: in Harlem, the Cooper Union, Chinatown, the Center for Jewish History, the Brooklyn Historical Society, the New-York Historical Society, the American Folk Art Museum, and many other sites of great interest. -

Beat Generation Icon William S. Burroughs Found Love – and Loved Life – During His Years in Lawrence

FOR BURROUGHS, IT ALL ADDED UP BURROUGHS CREEK TRAIL & LINEAR PARK Beat Generation icon William S. Burroughs found love – and loved life – during his years in Lawrence William S. Burroughs, once hailed by In 1943, Burroughs met Allen Ginsberg America after charges of obscenity were 11th Street Norman Mailer as “the only American and Jack Kerouac. They became fast rejected by the courts. In the meantime, novelist living today who may conceivably friends, forming the nucleus of the Burroughs had moved to Paris in 1958, be possessed by genius,” lived in Lawrence nascent Beat Generation, a group of working with artist Brion Gysin, then on a few blocks west of this spot for the last 16 often experimental writers exploring to London in 1960, where he lived for 14 13th Street years of his life. Generally regarded as one postwar American culture. years, publishing six novels. of the most influential writers of the 20th century, his books have been translated Burroughs became addicted to narcotics In 1974, Burroughs returned to 15th Street into more than 70 languages. Burroughs in 1945. The following year, he New York City where he met James was also one of the earliest American married Joan Vollmer, the roommate Grauerholz, a former University of multimedia artists; his films, recordings, of Kerouac’s girlfriend. They moved Kansas student from Coffeyville, paintings and collaborations continue to to a farm in Texas, where their son Kansas, who soon became Burroughs’ venue venue A A inspire artists around the world. He is the Billy was born. In 1948, they relocated secretary and manager. -

Le Memorie Di Un Film Notfilm Di Ross Lipman

Venezia Arti [online] ISSN 2385-2720 Vol. 26 – Dicembre 2017 [print] ISSN 0394-4298 Le memorie di un Film Notfilm di Ross Lipman Martina Zanco Abstract It’s been five decades since Film was first shown at the 26th edition of the Venice International Film Festival. Yet the 1965 short film, directed by Alain Schneider and based on the only script written for the big screen by Samuel Beckett, enjoys a new wave of interest. Digitally restored in 4k by filmmaker, archivist, preservationist and performer Ross Lipman, Film has began to tour the world once again, showing in many theaters, festivals and Cinematheques thanks to the tireless work of newly founded distribution company Reading Bloom and, well established, Milestone Films. This has re-opened discussion on the enigmatic short feature that, inspired from the metaphysical doctrine of irish philosopher George Berkeley, esse est percipi, sees an ‘Object’ (that is, the main character portrayed by Buster Keaton ) shadowed by an ‘Eye’. The main interest though, is in part due to the kino-essay, which is not a simple documentary, by Ross Lipman. In Notfilm, a documentary showed after Film at every screening, the director shows us the unseen cuts, unreleased material, photos, notes and audio recordings he rediscovered during the restoration process of the short film that raise an array of new, challenging questions (is Beckett Keaton alter ego?). Furthermore, this cine-essay seems to have another hidden layer, seemingly more ambitious and personal, that tries to go beyond Film itself. This is an aspect that, I think, is worth investigating. -

Courier Gazette 74*76 Newbert

Issued, Tuesday Thursday Saturday The Courier-Gazette 6 Entered as Second Class Mall Mattes THREE CENTS A COPY V olum e 94 Number 76. Established January, 1846. By The Courier-Gazette, 465 Main St, Rockland, Maine, Tuesday, June 27, 1939 The Courier-Gazette [EDITORIAL] THREE-TIMES-A-WEEK NOT ALL PAPER TALK UNDER A RIVER AND OVER IT Thomaston Church Wedding 'B B B B B B » Editor • The crisis in China is not to be disposed of in the careless WM. O FULLER Jk remark "all paper talk.” Existing there is a very serious situ Associate Editor With “The Sleepy City” On One Side and Wide PRANK A. WINSLOW ation, and which, through the presence of the destroyer Pillsbury might very easily involve the United States, as well Subscriptions »3.(i0 oer year payable Awake World’s Fair On the Other |o advance, single copies three cents. as Great Britain. The cockiness of Japan's attitude looks Advertising rates baaed u|>on clrcula-1 not unlike somebody ready to start a quarrel not necessarily lion and very reasonable NEWSPAPER HISTORY with Uncle Sam, but with Uncle Sam displaying a firmness (By The Roving Reporter Fourth Installment) The Rockland Qazette was estab-' which somebody else should have used long ago In the melee llshcd in 1846 In 1874 the Courier was started the day right. established and consolidated with the suppose the Pillsbury should be attacked! Suppose there 1'aaet.te In 1882 The Free Press was, should be a repetition of the Battleship Maine tragedy in Watermelons are plenty cheap ea'abllahed lh 1855 and lh 1891 changed Its name to the Tr'hune These papers i Havana harbor. -

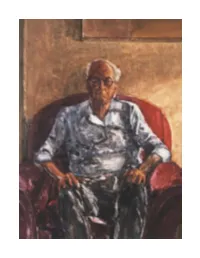

William Bronk

Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk David Clippinger Argotist Ebooks 2 * Cover image by Daniel Leary Copyright © David Clippinger 2012 All rights reserved Argotist Ebooks * Bill in a Red Chair, monotype, 20” x 16” © Daniel Leary 1997 3 The surest, and often the only, way by which a crowd can preserve itself lies in the existence of a second crowd to which it is related. Whether the two crowds confront each other as rivals in a game, or as a serious threat to each other, the sight, or simply the powerful image of the second crowd, prevents the disintegration of the first. As long as all eyes are turned in the direction of the eyes opposite, knee will stand locked by knee; as long as all ears are listening for the expected shout from the other side, arms will move to a common rhythm. (Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power) 4 Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk 5 Part I “So Large in His Singleness” By 1960 William Bronk had published a collection, Light and Dark (1956), and his poems had appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, Origin, and Black Mountain Review. More, Bronk had earned the admiration of George Oppen and Charles Olson, as well as Cid Corman, editor of Origin, James Weil, editor of Elizabeth Press, and Robert Creeley. But given the rendering of the late 1950s and early 1960s poetry scene as crystallized by literary history, Bronk seems to be wholly absent—a veritable lacuna in the annals of poetry. -

The End of Obscenity by Charles Rembar

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 57 | Issue 2 Article 13 1968 The ndE of Obscenity by Charles Rembar Paul Leo Oberst University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Oberst, Paul Leo (1968) "The ndE of Obscenity by Charles Rembar," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 57 : Iss. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol57/iss2/13 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1969] BOOK REviws THE END OF OBSCENITY. By Charles Rembar. New York: Random House, 1968. Pp. 528. $8.95. The End of Obscenity was written, the author tells us, in "an at- tempt to offer an insight, to those who are not a part of it, into how our legal system works."' This slows the book considerably for the legal reader,2 but should not dissuade him. It offers insights of other sorts to lawyers and to law students, since it is one of those all-too-rare books in which a lawyer unfolds the history of an important piece of litigation. The book begins with the author's retention by Grove Press in 1959 to defend Lady Chatterley's Lover3 and ends in 1966 with his successful defense of Fanny Hill4 for Putnam before the Supreme Court. -

Amy S. Wyngaard TRANSLATING SADE

Translating Sade Amy S. Wyngaard TRANSLATING SADE: THE GROVE PRESS EDITIONS, 1953–1968 n the last paragraph of their foreword to the 1965 Grove Press edition of IThe Complete Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom, and Other Writings, the translators Richard Seaver and Austryn Wainhouse quote the marquis de Sade’s wish, expressed in his last will and testament, that acorns be scattered over his grave, “in order that, the spot become green again, and the copse grown back thick over it, the traces of my grave may disappear from the face of the earth, as I trust the memory of me shall fade out of the minds of men” (xiv). Seaver and Wainhouse, who believed in the importance of Sade’s writings and were deeply invested in their efforts to produce the frst unexpurgated American translations of his works, express doubt that this prophecy would ever come to pass. The success of the Grove Press translations, however, has in fact caused certain aspects of Sade’s (critical) history to be forgotten. Five decades after their original publication in the 1960s, and two decades after their reissue in the early 1990s, these once-controversial editions of Sade’s works can now be considered mainstream. Widely referenced and readily available, they are more or less an accepted part of the American literary landscape, with only their original prefatory materials left to bear witness to what was one of the most fraught and revolutionary moments in the history of American publishing, not to mention Sade studies. Grove Press publisher Barney Rosset saw the publication of Sade’s works as integral to his fght for the freedom of the press. -

Writing Communities: Aesthetics, Politics, and Late Modernist Literary Consolidation

WRITING COMMUNITIES: AESTHETICS, POLITICS, AND LATE MODERNIST LITERARY CONSOLIDATION by Elspeth Egerton Healey A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor John A. Whittier-Ferguson, Chair Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Associate Professor Joshua L. Miller Assistant Professor Andrea Patricia Zemgulys © Elspeth Egerton Healey _____________________________________________________________________________ 2008 Acknowledgements I have been incredibly fortunate throughout my graduate career to work closely with the amazing faculty of the University of Michigan Department of English. I am grateful to Marjorie Levinson, Martha Vicinus, and George Bornstein for their inspiring courses and probing questions, all of which were integral in setting this project in motion. The members of my dissertation committee have been phenomenal in their willingness to give of their time and advice. Kali Israel’s expertise in the constructed representations of (auto)biographical genres has proven an invaluable asset, as has her enthusiasm and her historian’s eye for detail. Beginning with her early mentorship in the Modernisms Reading Group, Andrea Zemgulys has offered a compelling model of both nuanced scholarship and intellectual generosity. Joshua Miller’s amazing ability to extract the radiant gist from still inchoate thought has meant that I always left our meetings with a renewed sense of purpose. I owe the greatest debt of gratitude to my dissertation chair, John Whittier-Ferguson. His incisive readings, astute guidance, and ready laugh have helped to sustain this project from beginning to end. The life of a graduate student can sometimes be measured by bowls of ramen noodles and hours of grading.