Reforming Public Enterprises: Switzerland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Constance Regional Projects Take Shape

News analysis Lake Constance regional projects take shape Several projects are in the pipeline or already underway to upgrade rail links in the regional triangle between Germany, Austria and Switzerland, not to mention Liechtenstein a little further south. Anitra Green takes a look at the current state of play. N March this year an coherent vision for the their own benefit but also in stations re-opened, and I international group set up regional rail network. anticipation of cross-border existing stations upgraded. In to promote the development of Swiss engineer and cooperation projects designed addition, there would be a an S-Bahn network encircling transport planner Mr Paul to bring the various elements need to construct many more Lake Constance wrote to the Stopper, one of the initiators of together into a coherent, passing loops in Germany and governments of Switzerland, IBSB, says that with strong functional system. on the single-track lines in Austria, and Germany urging and organised backing at a An added motivation to Austria and Switzerland. them to invest in a programme local level, governments in develop the Lake Constance Part of this project is the of track-doubling and Brussels, Berlin, Vienna and S-Bahn is the three-month “Gürtelbahn” (belt line) electrification as a prerequisite Bern are more likely to lend “Nature in the City” garden initiative in Germany. This for regular-interval high- their support. show in Lindau in 2021, which involves electrifying the quality regional services. With passenger figures is expected to attract large Lindau - Friedrichshafen - The Lake Constance S-Bahn showing a steady increase at numbers of visitors. -

Postal Markings and Cancellations in Switzerland & Liechtenstein

Postal Markings and Cancellations in Switzerland & Liechtenstein Forward Shortly after this document was completed, a separate handbook on Swiss Railway Postmarks, by Alfred Müller and Roy Christian was published in 1977. In this more recent publication, Müller and Christian list the Travelling Post Office (TPO) cancellations according to the groupings recorded in the earlier handbook of Swiss Postal Cancellations “Grosses Handbuch der Schweizer Abstemplungen”, by Andres & Emmenegger. In recent years this latter publication has become known in its abbreviated form “Abstempelungs-Werk”, or simply “AW”. Felix Ganz, the author of the edited version you are about to read, used his own numbering system to describe the various different Key Types and Sub-Types of railway post office cancellations he had encountered. For the benefit of student philatelists interested in the Swiss Travelling Post Office, I have included the corresponding AW Group and Type alongside Felix’s original recordings. These appear in parentheses, in red bold type, e.g. (AW 83C/1) Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy from the original article, with additional information inserted wherever appropriate. The Helvetia Philatelic Society would welcome comments on this and any other article published on their website www.swiss-philately.co.uk Please address your correspondence to the Society’s webmaster at: [email protected] Published by the Helvetia Philatelic Society (Great Britain) Page 1 Postal Markings and Cancellations in Switzerland & Liechtenstein RAILWAY & STATION MARKINGS By Felix Ganz A coverage of several aspects of rail cancellations in Switzerland (there are none to speak of in Liechtenstein except for the Austrian railway from Buchs in Switzerland to Feldkirch in Austria that once upon a time stopped in Liechtenstein to pick up mail posted at the three stations, and then cancelled them with the Austrian TPO marks in use at that time) has been attempted and successfully achieved, but a complete picture of ALL aspects is yet to be written. -

Capacity Limitations. 1 Maintenance Windows

Appendix 3.5.2 to the Network Statement 2020 by SBB Infrastructure, Thurbo, Sensetalbahn and Hafenbahn Schweiz Version 1.0 Capacity limitations. This appendix lists the capacity limitations for the 2020 timetable year known at the time of the Network Statement 2020 going to print. They have been divided into the categories "renewals" and "expansions". The right to make changes is expressly reserved. Detailed information on capacity limitations is provided in good time in accordance with the FOT guideline on route closures according to Art. 11b of the Rail Network Access Ordinance (RailNAO). BLS Netz AG publishes the capacity limitations that apply to its network in its own Network Statement. 1 Maintenance windows 1.1 Basel–Brugg: maintenance at Bözberg Complete closure for focused maintenance on the route Pratteln–Stein-Säckingen–Brugg– Othmarsingen (excl.): 20 nights (4 weeks of 5 nights each, Sunday/Monday–Thursday/Friday), 21:30 to 05:30. Half capacity from 21:00 (single-track operation to permit overtaking). Limited diversion options via Olten VL (capacity). 1.2 Gotthard panoramic route Complete closure for maintenance and expansion work overnight on Sunday/Monday with flexible period of five hours. North-south guideline times: Erstfeld from 23:00 to 06:00, Airolo from 23:30 to 06:00, Bodio from 23:30 to 06:00. South-north guideline times: Bodio from 23:30 to 06:00, Airolo from 23:30 to 06:00, Erstfeld from 23:30 to 06:00. 1.3 Gotthard Base Tunnel Closure of one of the two tunnel tubes on Saturday/Sunday and Sunday/Monday night from 22:00 to 06:00. -

5. Und 6. August 2017 2 Freitag, 4

Jahrgang 2017 Freitag, den 4. August 2017 Nummer 31-33 5. und 6. August 2017 2 Freitag, 4. August 2017 Mitteilungsblatt Eriskirch NOTRUFE – BEREITSCHAFTSDIENST DER ÄRZTE / APOTHEKEN NOTRUF 110 RETTUNGSDIENST U. FEUERWEHR 112 ÄRZTLICHER BEREITSCHAFTSDIENST Telefon 116117; Montag, Dienstag, Donnerstag 18-8 Uhr, Mittwoch 13-8 Uhr, Freitag 16-8 Uhr. Samstag, Sonntag, Feiertage 8-8 Uhr Notfallpraxis am Klinikum Tettnang (ohne Anmeldung): Samstag, Sonntag und Feiertage: 8-21 Uhr. Kinderärztlicher Notdienst: 01801 - 929 290 Werktags 18.00 - 22.00 Uhr, danach Weiterleitung Kinderklinik Wochenende 8.00 - 20.00 Uhr, danach Weiterleitung Kinderklinik HNO-ärztl. Notdienst 01806 - 077211 Augenärztl. Notdienst 01801 - 929346 Zahnärztlicher Notdienst 01805 - 911620 Apothekennotdienst 0800 0022833 oder Handy 22833 Krankentransport 19222 Frauen helfen Frauen e.V. Klinikum Friedrichshafen (07541) 96-0 Tel.: (07541) 21800 NACHBARSCHAFTSHILFE Klinik Tettnang (07542) 5310 Frauenhaus Bodenseekreis, Organisierte Nachbarschaftshilfe Wasserschutzpolizei (07541) 28930 Notrufnummer (07541) 4893626 Rathaus (07541) 9708-0 Langenargen-Eriskirch-Kressbronn Weißer Ring Monika Baumann AIDS-BERATUNG Gemeinnütziger Verein zur Unterstützung Sprechzeiten: jeden 1. Freitag des Monats Gesundheitsamt (07541) 204-5860 von Kriminalitätsopfern und zur Verhütung von 13.30 - 15.30 Uhr im Bürgertreff, Sprechstunden: von Straftaten e.V., Greuther Straße 5 Mi. 15.00 - 17.00 Uhr Tel. (0180) 3343434 oder nach Vereinbarung unter der Betreuungsgruppe für Demenzkran- Kreuzbundgruppe Telefonnummer: 07543/96 42 67 ke des Deutschen Roten Kreuzes: mon- Selbsthilfegruppe für Suchtkranke und tags und mittwochs von 14-17 Uhr in der Angehörige DRK-Geschäftsstelle, Rotkreuzstr. 2, Fried- Treffen jeden Donnerstag, ab 19.30 Uhr, im SOZIALSTATION richshafen. Tel.: 07541/504-126 Pfarrgemeinde saal Mariabrunn. Kranken- und Altenpflege Selbsthilfe Tettnanger Zuckerle Kirchliche Besuchsdienste Klosterstr. -

Image Brochure Thurgau

We are Contact | General information on Thurgau and further addresses: Verwaltung des Kantons Thurgau | Thurgau Regierungsgebäude | CH-8510 Frauenfeld | Schweiz | Tel. +41 52 724 11 11 | Fax +41 52 724 29 93 | Internet: www.tg.ch | E-Mail: [email protected] The information brochure of Thurgau canton Impressum Publishers: The state chancellery of Thurgau canton | Executive Manager: 2 | 3 Introduction & Contents Walter Hofstetter, information office | Text: departments, information office, VetschCom | Editor, Realization: Hanspeter Vetsch, VetschCom, Frauenfeld | 4 | 5 Geography & Location Graphical Design: Barbara Ziltener, Visuelle Gestaltung, Frauenfeld | Photos: 6 | 7 Landscape & Residents Susann Basler, Müllheim | Translation: Betty Fahrni-Jones | Proofreader: 8 | 9 Life & Mobility Brigitte Ackermann, Maienfeld | Print and Lithography: Sonderegger Druck, 10 | 11 Economics & Work Weinfelden | Source of Supply: Informationsdienst Kanton Thurgau, 12 | 13 Education & Research Regierungs gebäude, 8510 Frauenfeld, Tel. +41 52 724 25 16, [email protected] 14 | 15 Culture & Leisure 16 | 17 State & Politics 18 | 19 History & Impressum The orchard of Switzerland Thurgau canton is the number one fruit-growing area in Switzer land. Every third apple is from here and is either for the table or for apple We are Thurgau – and we are proud of it. We explain why on the following pages. juice and cider. In Rogg wil there is Concise, colourful and with affection we present our canton to you. Take your time, an orchard containing trees with 300 different sorts of apples. The because Thurgau is often perceived on the second look, and then you get the drift. origin of all these various brands The gentle beauty of the softly rolling landscape with the lovely Lake Constance is an of apples is said to be the wild crab apple which was on the menu invitation to live, to work, to relax and to enjoy just being here. -

Neukirch Finden 2016

Treats from Switzerland. Swiss 100% plant-based gourmet Vegi-Service AG Bahnhofstrasse 52 CH-9315 Neukirch T: 071 470 04 04 F: 071 470 04 39 www.vegusto.ch [email protected] How to find us in Neukirch By car Singen Memmingen In the centre of Neukirch, take the roundabout towards Germany Bodensee/Lake Constance (Romanshorn). You will now be on Konstanz Bahnhofstrasse. After approx. 500 metres you will see a bakery Kreuzlingen Friedrichshafen on the right-hand side of the road. Romanshorn Fähre Our office building is 100 metres further on, on the opposite Winterthur Weinfelden Lake Constance side of the street. Amriswil Arbon A distinctive feature of our building is its glass front. Neukirch Altenrhein Zurich A1.1 Short-term parking is located in front of the building. If you are A1 Bregenz visiting us for longer, please park beyond the entrance to the St. Margrethen underground car park. St. Gallen A13 Austria railway station Neukirch-Egnach Lake Constance St. Gallen - Romanshorn railway car park entrance next to the underground car Bahnhofstrasse 52 park entrance Amriswil bus stop Bahnhofstrasse Amriswilerstrasse Volg Raiffeisenbank Post Neukirch Arbonerstrasse St. Gallerstrasse Arbon By public transit The Neukirch-Egnach railway station is on the Romanshorn - St. Gallen line. From Zurich, the fastest and least expensive way is to take the train to Amirswil and then take a coach to Neukirch Dorf . From the Neukirch Dorf stop, follow Bahnhofstrasse downhill (towards the lake) for about 500 metres to reach us. From Neukirch-Egnach station, take Bahnhofstrasse uphill (slight incline) towards Neukirch. Note: Please do not disembark at Egnach station. -

Erosion Hazards and Efficient Preservation Measures in Prehistoric Cultural Layers in the Littoral of Lake Constance (Germany, S

Erschienen in: Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites ; 18 (2016), 1-3. - S. 217-229 https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2016.1182757 Erosion Hazards and Efficient Preservation Measures in Prehistoric Cultural Layers in the Littoral of Lake Constance (Germany, Switzerland) Wolfgang Ostendorp,Frank Peeters and Hilmar Hofmann Limnologisches Institut der Universität Konstanz, Konstanz Helmut Schlichtherle Landesamt für Denkmalpflege (LAD) im Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart Gaienhofen-Hemmenhofen, Germany Hansjörg Brem Amt für Archäologie des Kantons Thurgau, Frauenfeld, Switzerland Many Neolithic and Bronze Age cultural layers and pile fields embedded in sediments at the shorelines of pre-alpine lakes in France, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, and Italy (in part UNESCO World Heritage Sites), are threatened by littoral erosion which is partly caused by human agency. Based on measurements of the wave field at four prehistoric sites on Lake Constance (Germany, Switzerland) we discuss the role of passenger ship navigation. We also review the stability and ecological compatibility of archaeological preservation control fills on the littoral platform of Lake Constance, and we make some recommendations for future preservation measures. KEYWORDS erosion markers, monitoring, sediments, UNESCO World Heritage, pile dwellings, waves, currents. Introduction The peri-alpine lake dwellings of the Neolithic and Bronze Age form the most prominent cluster of prehistoric wetland sites in Europe. From a total of 937 known sites, 111 were Konstanzer Online-Publikations-System (KOPS) URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-0-390198 218 FIGURE 1 Erosion at the prehistoric lake dwelling site of Sipplingen was triggered by retaining walls and harbour construction which have seriously affected cultural layers and wooden structures. -

Erosion and Archaeological Heritage Protection in Lake Constance And

conservation and mgmt of arch. sites, Vol. 14 Nos 1–4, 2012, 48–59 Erosion and Archaeological Heritage Protection in Lake Constance and Lake Zurich: The Interreg IV Project ‘Erosion und Denkmalschutz am Bodensee und Zürichsee’ Marion Heumüller Landesamt für Denkmalpfl ege, Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart, Germany Lake Constance and Lake Zürich contain important archaeological cultural assets. Above all the so-called pile dwellings of the fi fth to the fi rst millen- nium bc are widespread in the shallow water areas of the lakes, and in 2011 a total of twenty of these sites were included into the inscription of ‘Prehis- toric Pile Dwellings around the Alps’ on the UNESCO World Heritage List. However, construction in harbours and along the lakeshore, shipping traffi c, and recreational facilities as well as erosion processes all considerably endanger the stability of the underwater cultural assets. Since the 1980s the authorities concerned with the preservation of archaeological heritage in Baden-Württemberg and the cantons of Thurgau and Zürich have developed working techniques for the preservation of these special underwater cultural assets. Numerous questions about the causes of erosion, the technical installation and the effectivity of protective measures against erosion and the ecological tolerance of such measures, however, remain open. At this point the Interreg IV project ‘Erosion and Archaeological Heritage Protection on Lake Constance and Lake Zürich’, started in conjunction with various institutes concerned with lake research. Within the framework of this project the technical methods of mapping and surveillance of the site as a basis of an archaeological monitoring were refi ned and extended and meas- ures for the integration of protection against erosion were intensifi ed and checked. -

Focus on Stamps, the Collector's Magazine

9102/e 2uIss 9102/e Focus on stamps The Collector’s Magazine Land art + EUROPA – Birds + Fête des Vignerons 2019 (Winegrowers Festival) + 50 years manned Moon landing + much more SPECIAL OFFER for all “Focus on stamps” readers PREMIUM stockbooks Padded leather cover3, clear interleaves, black card with 9 clear strips per page Clear interleaves Black card with clear strips Special offer: CHF 49.90 instead of CHF 64.90 Cover colour / Ref. Stockbook Size Pages Binding Red Green Vlack Blue Excl. slipcase PREMIUM S64 A41 64 DLH2 337 807 332 495 319 358 301 419 1) The format corresponds approximately to A4 format. The precise A4 measures are 230 x 305 mm. 2) Double hinge binding. 3) LEFA = leather fi bre, consisting of leather fi bres and other renewable natural raw materials. ✁ Order form please send to: Tel. 0848 66 55 44 · Fax 058 667 62 68 Post CH Ltd – PostalNetwork – Retail Logistics – Werkstrasse 41 – 3250 Lyss K ___ Ref. 337 807, stockbook, red CHF 49.90 K ___ Ref. 319 358, stockbook, black CHF 49.90 K ___ Ref. 332 495, stockbook, green CHF 49.90 K ___ Ref. 301 419, stockbook, blue CHF 49.90 Delivery only in Switzerland Customer: Method of payment (for new customers - please select only one payment method) If you are already a customer, your usual method of payment will be applied. Last name/First name: Switzerland ❑ with invoice ❑ debit from postal account (IBAN): Street/No.: C H Postcode/City: Credit cards ❑ American Express ❑ VISA ❑ Diners Club ❑ Eurocard/Mastercard® Date of birth: Credit card no. -

Hermann Hesse on Lake Constance Lecture Given by Volker Michels

“As far away from Berlin as I can get!” Hermann Hesse on Lake Constance Lecture given by Volker Michels Hermann Hesse was 27 when he came to Gaienhofen, and 35 when he moved away again. He thus lived there for just under 8 years (from 1904 to 1912), a period equivalent to a bare tenth of his life. Yet it was a period that was to prove formative both in terms of his own future development and also for the Untersee region, the part of the “Swabian Sea” where the Rhine flows out of the lake, and the area that has remained the most beautiful and quietest section of Lake Constance (“Bodensee” in German) right up to the present day. For this stretch of country, as later in the case of southern Switzerland, Hesse’s decision to settle there marked the beginning of a period in which many other artists were drawn to the region. Yet it never became a homogenous artists’ colony - not a Worpswede on Lake Constance, in other words - no matter how numerous the motivations shared by the fellow writers and artists that lived there, a community seeking to live an alternative lifestyle far away from the devastations of civilization and industrialization in countryside that had remained intact and unspoilt. And they knew why they decided to do so. None of them came to the region from the provinces but from big cities: Hesse from Basel, Otto Dix from Berlin and Düsseldorf, Erich Heckel from Dresden and Berlin. Where, after all, is one more aware of the disparities, and better able to depict them, than when confronted with the unspoilt obverse of the denaturization -

Lake Constance Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

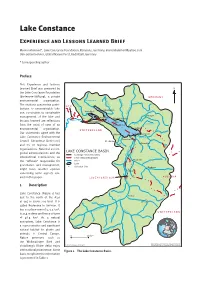

Lake Constance Experience and Lessons Learned Brief Marion Hammerl*, Lake Constance Foundation, Konstanz, Germany, [email protected] Udo Gattenloehner, Global Nature Fund, Radolfzell, Germany * Corresponding author Preface This Experience and Lessons Learned Brief was prepared by 1 the Lake Constance Foundation (Bodensee-Stiftung), a private *(50$1< 6HHIHOGHU5 5 RWDFK5 environmental organization. 5 6WRFNDFKHU5 DGROI]HOOHU5 The sections concerning contri- *(5 butions to unsustainable lake 8EHUOLQJHU6HH 8EHUOLQJHQ use, constraints to sustainable 5DGROI]HOO 6FKXVVHQ5 =HOOHU :DQJHQ management of the lake and 6HH .RQVWDQ] )ULHGULFKVKDIHQ lessons learned are refl ections 5KHLQ5 .UHX]OLQJHQ /DNH $UJHQ5 /HLEODFK5 from the point of view of an &RQVWDQFH environmental organization. /LQGDX 6:,7=(5/$1' Our statements agree with the $UERQ %UHJHQ] % UH Lake Constance Environmental JHQ]HU5 5RUVFKDFK Council (Umweltrat Bodensee) 6W*DOOHQ and its 18 regional member 'RUQELUQ organizations. National and re- gional administrations and the /$.(&2167$1&(%$6,1 5KHLQ5 'UDLQDJH%DVLQ%RXQGDU\ $OWHU5KHLQ5 international commissions, as ,QWHUQDWLRQDO%RXQGDU\ the “offi cials” responsible for 5LYHU )HOGNLUFK governance and management, /DNH 6HOHFWHG&LW\ %OXGHQ] might have another opinion 9DGX] concerning some aspects cov- ered in this paper. /,(&+7(167(,1 $8675,$ 5KHLQ5 1. Description Lake Constance (Figure 1) lies just to the north of the Alps &KXU at 395 m above sea level. It is 'DYRV called Bodensee in German. It 2 $ has a surface area of 571.5 km , O 9RUGHUUKHLQ5 EX OD5 6:,7=(5/$1' is 254 m deep and has a volume *ORJQ5 3 of 48.5 km . As a natural DELXVD5 5 ecosystem, Lake Constance is a representative and signifi cant natural habitat for plants and +LQWHUUKHLQ5 animals in Central Europe. -

INVITATION 10 YEARS of RE/MAX SWITZERLAND FRIDAY, 25 JUNE 2010 R Welcome Aboard!

INVITATION 10 YEARS OF RE/MAX SWITZERLAND FRIDAY, 25 JUNE 2010 R Welcome aboard! Valued RE/MAX colleagues, Please make yourselves at home and enjoy the great speakers in one of the most extraordinary event locations. The exclusive event ship «MS Sonnenkönigin» offers a unique space to celebrate our 10-year anniversary. Thanks to your daily dedication and the success it has pro- duced, RE/MAX Switzerland has become the market leader. We‘ve laid a strong foundation in the last 10 years, and this is an ideal time to move on to new pastures. We‘re on track towards our next goal of a 10% market share. At our 10-year anniversary on 25 June 2010, we will navi- gate you through an exciting day and an unforgettable evening. Please make yourselves comfortable and discover on the next few pages all that awaits you. The unique ambiance gives you the opportunity to expand your network with new contacts, foster existing relationships and get inspired through enthusi- asm, focus and performance as well as through precision and a readiness to act. We look forward to personally welcoming you to this one-of-a-kind, special class event! Teddy Keifer Marco Röllin CEO RE/MAX Switzerland Managing Director RE/MAX Switzerland Schedule Friday, 25 June 2010, 9:00 a.m. 09:00 Boarding, Rorschach Harbour 09:30 B/O Meeting → Main deck 12:00 Stand-up buffet lunch → Upper deck I+II 13:00 Boarding, Welcome Apéro → Upper deck I+II 14:00 Convention for agents, Broker/Owner and guests → Main deck 17:00 Apéro, World Cup match 2nd half Portugal–Brazil → Upper deck II, Sun deck 19:00 Dinner → Main deck, Upper deck I+II 20:30 Live broadcast, match Switzerland–Honduras → Upper deck II 21:00 Party → All decks 23:00 Highlight 02:00 Closing Our contributors, speakers Teddy Keifer (1) CEO RE/MAX Switzerland Teddy Keifer signed the master franchise agreement in 1999 – The fi rst offi ce was opened in autumn 2000 – He signed the hundredth broker in 2003 – In 2004 he opened the hundredth offi ce.