Hermann Hesse on Lake Constance Lecture Given by Volker Michels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Federal State of Hesse

Helaba Research REGIONAL FOCUS 7 August 2018 Facts & Figures: The Federal State of Hesse AUTHOR The Federal Republic of Germany is a country with a federal structure that consists of 16 federal Barbara Bahadori states. Hesse, which is situated in the middle of Germany, is one of them and has an area of just phone: +49 69/91 32-24 46 over 21,100 km2 making it a medium-sized federal state. [email protected] EDITOR Hesse in the middle of Germany At 6.2 million, the population of Hesse Dr. Stefan Mitropoulos/ Population in millions, 30 June 2017 makes up 7.5 % of Germany’s total Anna Buschmann population. In addition, a large num- PUBLISHER ber of workers commute into the state. Dr. Gertrud R. Traud As a place of work, Hesse offers in- Chief Economist/ Head of Research Schleswig- teresting fields of activity for all qualifi- Holstein cation levels, for non-German inhabit- Helaba 2.9 m Mecklenburg- West Pomerania ants as well. Hence, the proportion of Landesbank Hamburg 1.6 m Hessen-Thüringen 1.8 m foreign employees, at 15 %, is signifi- MAIN TOWER Bremen Brandenburg Neue Mainzer Str. 52-58 0.7 m 2.5 m cantly higher than the German aver- 60311 Frankfurt am Main Lower Berlin Saxony- age of 11 %. phone: +49 69/91 32-20 24 Saxony 3.6 m 8.0 m Anhalt fax: +49 69/91 32-22 44 2.2 m North Rhine- Apart from its considerable appeal for Westphalia 17.9 m immigrants, Hesse is also a sought- Saxony Thuringia 4.1 m after location for foreign direct invest- Hesse 2.2 m 6.2 m ment. -

Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann

Naharaim 2014, 8(2): 210–226 Uri Ganani and Dani Issler The World of Yesterday versus The Turning Point: Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann “A turning point in world history!” I hear people saying. “The right moment, indeed, for an average writer to call our attention to his esteemed literary personality!” I call that healthy irony. On the other hand, however, I wonder if a turning point in world history, upon careful consideration, is not really the moment for everyone to look inward. Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man1 Abstract: This article revisits the world-views of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann by analyzing the diverse ways in which they shaped their literary careers as autobiographers. Particular focus is given to the crises they experienced while composing their respective autobiographical narratives, both published in 1942. Our re-evaluation of their complex discussions on literature and art reveals two distinctive approaches to the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as two alternative concepts of authorial autonomy within society. Simulta- neously, we argue that in spite of their different approaches to political involve- ment, both authors shared a basic understanding of art as an enclave of huma- nistic existence at a time of oppressive political circumstances. However, their attitudes toward the autonomy of the artist under fascism differed greatly. This is demonstrated mainly through their contrasting portrayals of Richard Strauss, who appears in both autobiographies as an emblematic genius composer. DOI 10.1515/naha-2014-0010 1 Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, trans. -

Investigations on the Caesium–137 Household of Lake Lugano, Switzerland

Caesium–137 Household of Lake Lugano INVESTIGATIONS ON THE CAESIUM–137 HOUSEHOLD OF LAKE LUGANO, SWITZERLAND J. DRISSNER, E. KLEMT*), T. KLENK, R. MILLER, G. ZIBOLD FH Ravensburg Weingarten, University of Applied Sciences, Center of Radioecology, P. O. Box 1261, D 88241 Weingarten, Germany M. BURGER, A. JAKOB GR, AC Laboratorium Spiez, Sektion Sicherheitsfragen, Zentrale Analytik und Radiochemie, CH 3700 Spiez, Switzerland *) [email protected] SedimentCaesium–137J. Drissner, E. HouseholdKlemt, TH. of Klenk Lake et Lugano al. samples were taken from different basins of Lake Lugano, and the caesium 137 inventory and vertical distribution was measured. In all samples, a distinct maximum at a depth of 5 to 10 cm can be attributed to the 1986 Chernobyl fallout. Relatively high specific activities of 500 to 1,000 Bq/kg can still be found in the top layer of the sediment. 5 step extraction experiments on sediment samples resulted in percentages of extracted caesium which are a factor of 2 to 8 higher than those of Lake Constance, where caesium is strongly bound to illites. The activity concentration of the water of 3 main tributaries, of the outflow, and of the lake water was in the order of 5 to 10 mBq/l. 1 Introduction Lake Lugano with an area of 48.9 km2 and a mean depth of 134 m is one of the large drinking water reservoirs of southern Switzerland, in the foothills of the southern Alps. The initial fallout of Chernobyl caesium onto the lake was about 22,000 Bq/m2 [1], which is similar to the initial fallout of about 17, 000 Bq/m2 onto Lake Constance, which is located in the prealpine area of southern Germany (north of the Alps). -

Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature Melanie Jessica Adley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Adley, Melanie Jessica, "Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 729. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/729 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/729 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature Abstract How fragile is the femme fragile and what does it mean to shatter her fragility? Can there be resistance or even strength in fragility, which would make it, in turn, capable of shattering? I propose that the fragility embodied by young women in fin-de-siècle Vienna harbored an intentionality that signaled refusal. A confluence of factors, including psychoanalysis and hysteria, created spaces for the fragile to find a voice. These bourgeois women occupied a liminal zone between increased access to opportunities, both educational and political, and traditional gender expectations in the home. Although in the late nineteenth century the femme fragile arose as a literary and artistic type who embodied a wan, ethereal beauty marked by delicacy and a passivity that made her more object than authoritative subject, there were signs that illness and suicide could be effectively employed to reject societal mores. -

Around the Lake Constance in One Week Arrival

Around the Lake Constance in one week Individual tour Category: bike tour Duration: 7 days Offer: 2021 Meals: breakfasts Accommodation: hotels and pensions, rooms with bathrooms Difficulty: easy Distance by bike: 230 - 250 km The tour around Lake Constance is one of cycling classics. It is among the biggest lakes of Central Europe, along the Balaton and Lake Geneva. It is located at the border of Switzerland, Germany and Austria. At the same time, it is a very interestingly located one, surrounded by the Alpine mountains, allowing to observe many peaks, and numerous castles if the weather allows. The lake is encircled by a cycling route, making the trip a safe and comfortable one. Due to minor elevations we recommend the tour even for beginners and families with children. Arrival: By plane – the easiest way is coming by plane to Friedrichshafen, Stuttgart or Zurich. Most flights can be booked to Zurich, often at a reasonable price. From there, one should take a train to Constance. Places to see: Constance Over 600 years ago, the ecumenical council ending the Western schism took place in Constande. During the council, pope Martin V was elected, and the Czech reformer Jan Hus was burned at the stake at the same time. The statue of Imperia by Peter Lenk commemorates these events. Erected in 1993, weighing over 18 tons and 9 meters tall is one of the city’s symbols. It resembles a courtesan with her hands risen up, holding two naked men. One of them is wearing a crown and holds a sphere – the symbol of Holy Roman Empire. -

Radgeber Im Landkreis Konstanz Sehr Geehrte Leserin, Sehr Geehrter Leser

Aufsatteln mit dem RadGEBER im Landkreis Konstanz Sehr geehrte Leserin, sehr geehrter Leser, Sie halten den ersten „Rad“- Geber des Landkreises Konstanz in Ihren Händen. Mit diesem Heft möchten wir Sie für das Radfahren im Alltag und in der Freizeit begeistern. Im RadGEBER finden Sie dazu praktische Infos für Ihre Fahrten. Fahrradfahren macht Spaß – und das wollen wir mit unserem RadGEBER vermitteln! Seit 2019 sind wir offizieller RadKULTUR-Kreis des Landes Baden-Württemberg und setzen uns als solcher für mehr Freude am Radfahren im Alltag ein. Denn egal ob auf dem Weg zur Arbeit oder zur Schule: Vor allem für kurze Wege ist das Fahrrad die ideale Wahl, um fit und flexibel von A nach B zu kommen. Ich lade Sie deshalb herzlich ein: Probieren Sie es aus und entdecken Sie das Radfahren für sich ! Viel Spaß mit dem RadGEBER und gute Fahrt! Ihr Zeno Danner Landrat des Landkreises Konstanz © Ulrike Sommer Portrait: 2 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis Radfahren? Na klar! 10 Gründe fürs Fahrrad / 6 Auf einen Blick: Nützliches fürs Radfahren im Landkreis Konstanz / 12 24h-Reparaturservice: Die RadSERVICE-Punkte / 22 Mit dem Radroutenplaner in Baden-Württemberg bequem ans Ziel / 25 Clever unterwegs: Fahrrad-Mitnahme im ÖPNV / 28 Radfahren in der Freizeit: Themenrouten im Landkreis Konstanz / 30 Serviceartikel: Fahrradpflege leicht gemacht / 34 4 5 10 Gründe fürs Radfahren im Alltag 1/ Radfahren macht Spaß 3/ Radfahren ist unkompliziert Viele Menschen erinnern sich noch an den Moment, als sie im Fahrradfahren ist nach dem Zufußgehen die einfachste aller Kindesalter zum ersten Mal im Fahrradsattel saßen. An das Möglichkeiten, um auf kurzen Wegen ohne viel Aufwand ans Gefühl der Freiheit, sobald man selbstständig in die Pedale Ziel zu kommen. -

Escaping Liberty: Western Hegemony, Black Fugitivity Barnor Hesse Political Theory 2014 42: 288 DOI: 10.1177/0090591714526208

Political Theory http://ptx.sagepub.com/ Escaping Liberty: Western Hegemony, Black Fugitivity Barnor Hesse Political Theory 2014 42: 288 DOI: 10.1177/0090591714526208 The online version of this article can be found at: http://ptx.sagepub.com/content/42/3/288 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Political Theory can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ptx.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ptx.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - May 14, 2014 What is This? Downloaded from ptx.sagepub.com by guest on May 20, 2014 PTXXXX10.1177/0090591714526208Political TheoryHesse 526208research-article2014 Article Political Theory 2014, Vol. 42(3) 288 –313 Escaping Liberty: © 2014 SAGE Publications Reprints and permissions: Western Hegemony, sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0090591714526208 Black Fugitivity ptx.sagepub.com Barnor Hesse1 Abstract This essay places Isaiah Berlin’s famous “Two Concepts of Liberty” in conversation with perspectives defined as black fugitive thought. The latter is used to refer principally to Aimé Césaire, W. E. B. Du Bois and David Walker. It argues that the trope of liberty in Western liberal political theory, exemplified in a lineage that connects Berlin, John Stuart Mill and Benjamin Constant, has maintained its universal meaning and coherence by excluding and silencing any representations of its modernity gestations, affiliations and entanglements with Atlantic slavery and European empires. This particular incarnation of theory is characterized as the Western discursive and hegemonic effects of colonial-racial foreclosure. Foreclosure describes the discursive contexts in which particular terms or references become impossible to formulate because the means by which they could be formulated have been excluded from the discursive context. -

Ab Schaffhausen/Konstanz

Schiffsfahrplan 2019 Untersee und Rhein Radolfzell Insel Reichenau Iznang Schaffhausen Büsingen Gailingen Neuhausen Gaienhofen Untersee am Rheinfall Hemmen hofen Bodenseeforum Stein am Rhein Diessenhofen Wangen Konstanz Rheinfall Rhein Öhningen Berlingen Ermatingen Bodensee Steckborn Mannenbach Gottlieben Mammern Kreuzlingen Richtung Kreuzlingen Richtung Schaffhausen Kurse www.bsb.de CourseKurs | Schedule 525 533 543 551 CourseKurs | Schedule 528 536 550 558 Wichtige Informationen PrintempsFrühjahr • Spring 1 Schaffhausen 9.10 1 11.10 13.18 15.18 Kreuzlingen 9.00 11.00 14.27 1 16.27 Büsingen, Bodenseeforum : Halt auf Verlangen Büsingen 1 9.38 11.38 13.46 15.46 Konstanz 9.12 11.12 14.39 16.39 nicht alle Kurse / Haltestellen, z.T. nur Handrollstühle 13. 04. – 28. 04. 2019 1 Diessenhofen / Bodenseeforum 9.17 11.17 14.44 16.44 Restaurant auf allen Kursschiffen. « Schiffs-Frühstück » Do – So, allg. Feiertage Gailingen 10.10 12.10 14.18 16.18 auf den Kursen 525 und 528. Jeu – Dim, fêtes générales Gottlieben 9.32 11.32 14.59 16.59 Stein am Rhein 11.15 13.15 15.23 17.23 Allgemeine Feiertage: Karfreitag 19. April, Ostermontag 22. Thu – Sun, public holidays Ermatingen 9.52 11.52 15.19 17.19 April, Tag der Arbeit 1. Mai, Auffahrt 30. Mai, Pfingst montag 10. Juni, Fronleichnam 20. Juni Öhningen 11.32 13.32 15.40 17.40 Reichenau 10.06 12.06 15.33 17.33 Mammern 11.39 13.39 15.47 17.47 Fahrkarten an Bord der Schiffe erhältlich. 29. 04. – 21. 06. 2019 Mannenbach 10.13 12.13 15.40 17.40 Wangen 11.45 13.45 15.53 17.53 Gültig: GA, Halbtax ( 50 % ), Tageskarte zum Halbtax, täglich Berlingen 10.23 12.23 15.50 17.50 OSTWIND-Tageskarte Plus, Gemeinde-Tageskarte. -

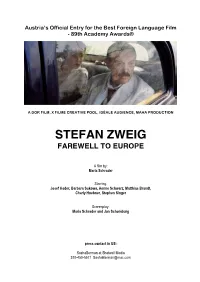

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

Grundlagenbericht Gesamtrevision [Pdf, 4.5

Politische Gemeinde Wagenhausen Gesamtrevision der Kommunalplanung Grundlagenbericht Situation – Ziele – Handlungsbedarf Entwurf vom 29. Oktober 2018, Version 1.2, mit Pendenzen (gelb) Bearbeitung (Nr. 2101): Winzeler + Bühl | Rheinweg 21 | 8200 Schaffhausen | Tel. 052 624 32 32 | [email protected] 2 Gesamtrevision Kommunalplanung Wagenhausen: Entwurf Grundlagenbericht vom 29.10.2018 Gesamtrevision Kommunalplanung Wagenhausen: Entwurf Grundlagenbericht vom 29.10.2018 3 Inhalt 1 Einleitung ..................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Ausgangslage .................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Gründe für eine Gesamtrevision ...................................................................................... 6 1.3 Revisionsziele ................................................................................................................. 6 1.4 Wichtige übergeordnete Planungsgrundlagen ................................................................. 7 2 Organisation ................................................................................................................ 8 2.1 Projektorganisation .......................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Planungsablauf, Zeitbedarf .............................................................................................. 9 2.3 Information- und Mitwirkung der Bevölkerung -

Hermann Hesse Sein Leben Und Sein Werk

Hermann Hesse Sein Leben und sein Werk Hugo Ball Das Vaterhaus Hermann Hesse ist geboren am 2. Juli 1877 in dem württembergischen Städtchen Calw an der Nagold. Beide Eltern waren nicht Schwaben von Geburt. Johannes Hesse, der Vater des Dichters, war seinen Papieren nach russischer Untertan, aus Weißenstein in Estland; seine Familie kam dorthin aus Dorpat und hat baltisches Gepräge; der älteste nachweisbare Familienahn kam aus Lübeck und war hanseatischer Soldat. Die Mutter des Dichters, Marie Gundert-Dubois, Tochter von Dr. Hermann Gundert-Dubois, wurde als Missionarstochter geboren in Talatscheri (Ostindien). Dem Blute und Temperamente nach kommt ihre Mutter, eine geborene Dubois, aus der Gegend von Neuchâtel und aus calvinistischer Winzerfamilie. Die von dem hanseatischen Soldaten Barthold Joachim stammenden Hesses (Vater und Sohn) zeigen einen schmalen, eher schmächtigen Typus von zartem Gliederbau; sie haben blaue, scharfe Augen und helles Haar; angespannte, habichtartige Gesichtszüge und in der Erregung spitzige, rückwärtsfliehende Ohren. Sie zeigen gefaßte Haltung, bei seelischer Berührung Schüchternheit, die sich überraschend in jähen Zorn wandeln kann; zähes, stilles, geduldig zuwartendes Wesen und Neigung zu einer edlen, ritterlichen Geselligkeit. Die Dubois (Mutter und Tochter) sind klein und schmal von Statur. Sie haben engsitzende, feurig-dunkle Augen; lebhaftes, nervöses, sanguinisches Temperament. Sie sind religiös verschwärmt und von innerer Glut verzehrt: heroische Frauen in ihren Vorsätzen und Zielen, in ihrer Hingabe und Leidenschaft; hochgemut bis zum Empfinden ihrer Überlegenheit und ihres Isoliertseins, milde aber und gütig in ihrem Werben um die ihnen Anvertrauten, worunter sie keineswegs nur die eigene Familie verstehen, sondern weit darüber hinaus die Familie der Menschenbrüder und -schwestern, die Gemeinde der gleich ihnen Opferbereiten, der Auserwählten und Heiligen. -

Prehistoric Pile Dwellings Around the Alps

Prehistoric Pile Dwellings around the Alps World Heritage nomination Switzerland, Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Slovenia Executive Summary Volume I 2 – Executive Summary Volume I Executive Summary Countries Switzerland (CH) Austria (AT) France (FR) Germany (DE) Italy (IT) Slovenia (SI) State, Province or Region Switzerland Cantons of Aargau (AG), Berne (BE), Fribourg (FR), Geneva (GE), Lucerne (LU), NeucHâtel (NE), Nidwalden (NW), ScHaffHausen (SH), ScHwyz (SZ), SolotHurn (SO), St. Gall (SG), THurgau (TG), Vaud (VD), Zug (ZG), Zurich (ZH). Austria — Federal state of CarintHia (Kärnten, KT): administrative district (Verwaltungsbezirk) of Klagenfurt-Land; — Federal state of Upper Austria (OberösterreicH, OÖ): administrative district (Verwaltungsbezirk) of Vöcklabruck. France — Region of RHône-Alpes: Départements of Savoie (73), Haute-Savoie (74); — Region of Franche-Comté: Département of Jura (39). Germany — Federal state of Baden-Württemberg (BW): administrative districts (Landkreise) of Alb-Donau-Kreis (UL), BiberacH (BC), Bodenseekreis (FN), Konstanz (KN), Ravensburg (RV); — Free State of Bavaria (BY): administrative districts (Landkreise) of Landsberg am Lech (LL); Starnberg (STA). 3 Volume I Italy — Region of Friuli Venezia Giulia (FV): Province of Pordenone (PN); — Region of Lombardy (LM): Provinces of Varese (VA), Brescia (BS), Mantua (MN), Cremona (CR); — Region of Piedmont (PM): Provinces of Biella (BI), Torino (TO); — Trentino-South Tyrol / Autonomous Province of Trento (TN); — Region of Veneto (VN): Provinces of Verona (VR), Padua (PD). Slovenia Municipality of Ig Name of Property PreHistoric Pile Dwellings around the Alps Sites palafittiques préHistoriques autour des Alpes Geographical coordinates to the nearest second The geograpHical coordinates to the nearest second are sHown in ÿ Figs. 0.1–0.6 . Switzerland Component Municipality Place name Coordinates of Centre Points UTM Comp.