The Kenya 1997 General Elections in Maasailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Motions Tracker 2016

REPUBLIC OF KENYA THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY ELEVENTH PARLIAMENT (FOURTH SESSION) MOTIONS TRACKER 2016 The Motions Tracker provides an overview of the current status of all Motions before the National Assembly during the year. NO. SUBJECT NOTICE OF PROPOSER SECONDER DIVISION DEBATED REMARKS MOTION AND CONCLUDED 1. THAT pursuant to the provisions of Standing 9/2/2016 Hon. Katoo Ole Hon. Thomas 9/2/2016 Adopted Order No. 171(1)(d), this House approves the Metito, MP Mwadeghu, appointment of Members to the House Business (Majority Party MP (Minority Committee in addition to the Members specified Whip) Party Whip) under paragraph (a) (b) & (c). 2. THAT, notwithstanding the provisions of 10/2/2016 Hon. Aden Hon. Chris 10/2/2016 Adopted Standing Order 97(4), this House orders that, Duale, MP Wamalwa, each speech in a debate on Bills sponsored by (Leader of the MP (Deputy a Committee, the Leader of the Majority Majority Party) Minority Party or the Leader of the Minority Party be Party Whip) limited as follows:- A maximum of forty five (45) minutes for the Mover, in moving and fifteen minutes (15) in replying, a maximum of thirty (30) minutes for the Chairperson of the relevant Committee (if the Bill is not sponsored by the relevant Committee), and a maximum of ten (10) minutes for any other Member Status as at Thursday, 22nd December, 2016 The National Assembly 1 NO. SUBJECT NOTICE OF PROPOSER SECONDER DIVISION DEBATED REMARKS MOTION AND CONCLUDED speaking, except the Leader of the Majority Party and the Leader of the Minority Party, who shall be limited to a maximum of fifteen Minutes (15) each (if the Bill is not sponsored by either of them); and that priority in speaking be accorded to the Leader of the Majority Party, the Leader of the Minority Party and the Chairperson of the relevant Departmental Committee, in that Order. -

Race for Distinction a Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya

Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 09 December 2015 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Stephen Smith (EUI Supervisor) Prof. Laura Lee Downs, EUI Prof. Romain Bertrand, Sciences Po Prof. Daniel Branch, Warwick University © Connan, 2015 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Race for Distinction. A Social History of Private Members’ Clubs in Colonial Kenya This thesis explores the institutional legacy of colonialism through the history of private members clubs in Kenya. In this colony, clubs developed as institutions which were crucial in assimilating Europeans to a race-based, ruling community. Funded and managed by a settler elite of British aristocrats and officers, clubs institutionalized European unity. This was fostered by the rivalry of Asian migrants, whose claims for respectability and equal rights accelerated settlers' cohesion along both political and cultural lines. Thanks to a very bureaucratic apparatus, clubs smoothed European class differences; they fostered a peculiar style of sociability, unique to the colonial context. Clubs were seen by Europeans as institutions which epitomized the virtues of British civilization against native customs. In the mid-1940s, a group of European liberals thought that opening a multi-racial club in Nairobi would expose educated Africans to the refinements of such sociability. -

Special Issue the Kenya Gazette

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXV_No. 64 NAIROBI, 19th April, 2013 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 5381 THE ELECTIONS ACT (No. 24 of 2011) THE ELECTIONS (PARLIAMENTARY AND COUNTY ELECTIONS) PETITION RULES, 2013 ELECTION PETITIONS, 2013 IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 75 of the Elections Act and Rule 6 of the Elections (Parliamentary and County Elections) Petition Rules, 2013, the Chief Justice of the Republic of Kenya directs that the election petitions whose details are given hereunder shall be heard in the election courts comprising of the judges and magistrates listed and sitting at the court stations indicated in the schedule below. SCHEDULE No. Election Petition Petitioner(s) Respondent(s) Electoral Area Election Court Court Station No. BUNGOMA SENATOR Bungoma High Musikari Nazi Kombo Moses Masika Wetangula Senator, Bungoma Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition IEBC County Muthuku Gikonyo No. 3 of 2013 Madahana Mbayah MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT Bungoma High Moses Wanjala IEBC Member of Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Lukoye Bernard Alfred Wekesa Webuye East Muthuku Gikonyo No. 2 of 2013 Sambu Constituency, Bungoma Joyce Wamalwa, County Returning Officer Bungoma High John Murumba Chikati I.E.B.C Member of Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Returning Officer Tongaren Constituency, Muthuku Gikonyo No. 4 of 2013 Eseli Simiyu Bungoma County Bungoma High Philip Mukui Wasike James Lusweti Mukwe Member of Parliament, Justice Hellen A. Bungoma Court Petition IEBC Kabuchai Constituency, Omondi No. 5 of 2013 Silas Rotich Bungoma County Bungoma High Joash Wamangoli IEBC Member of Parliament, Justice Hellen A. -

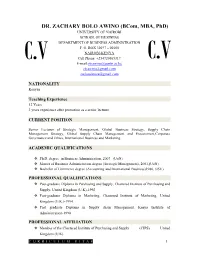

DR. ZACHARY BOLO AWINO (Bcom, MBA, Phd) UNIVERSITY of NAIROBI SCHOOL of BUSINESS DEPARTMENT of BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION P

DR. ZACHARY BOLO AWINO (BCom, MBA, PhD) UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI SCHOOL OF BUSINESS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION P. O. BOX 30197 – 00100 NAIROBI-KENYA Cell Phone: +254720565317 E-mail:[email protected] [email protected] [email protected] NATIONALITY Kenyan Teaching Experience 12 Years 3 years experience after promotion as a senior lecturer CURRENT POSITION Senior Lecturer of Strategic Management, Global Business Strategy, Supply Chain Management Strategy, Global Supply Chain Management and Procurement,Corporate Governance and Ethics, International Business and Marketing. ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS Ph.D. degree in Business Administration, 2007 –(UoN) Master of Business Administration degree (Strategic Management), 2001,(UoN). Bachelor of Commerce degree (Accounting and International Business)1986, (JSU) PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS Post-graduate Diploma in Purchasing and Supply, Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply, United Kingdom (U.K)-1992 Post-graduate Diploma in Marketing, Chartered Institute of Marketing, United Kingdom (U.K.)-1994 Post graduate Diploma in Supply chain Management, Kenya Institute of Administration-1990 PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATION Member of the Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply (CIPS) United Kingdom (U.K) C U R R I C U L U M V I T A E 1 Member of the Chartered Institute of Marketing (CIM) United Kingdom (U.K) Member of Marketing Society of Kenya (MSK) Member of the International Purchasing and Supply Education and Research Association (IPSERA) Coventry, United Kingdom (U.K) Member -

International Journal of Innovative Research and Knowledge Volume-6 Issue-5, May 2021

International Journal of Innovative Research and Knowledge Volume-6 Issue-5, May 2021 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE ISSN-2213-1356 www.ijirk.com A HISTORY OF CONFLICT BETWEEN NYARIBARI AND KITUTU SUB-CLANS AT KEROKA IN NYAMIRA AND KISII COUNTIES, KENYA, 1820 - 2017 Samuel Benn Moturi (MA-History), JARAMOGI OGINGA ODINGA, UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY GESIAGA SECONDARY SCHOOL, P.O Box 840-40500 Nyamira-Kenya Dr. Isaya Oduor Onjala (PhD-History), JARAMOGI OGINGA ODINGA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, P.O Box 210-40601, Bondo-Kenya Dr. Fredrick Odede (PhD-History), JARAMOGI OGINGA ODINGA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, P.O Box 210-40601, Bondo-Kenya ABSTRACT A lot of research done on conflict and disputes between communities, nations and organized groups across the globe. Little, however done on conflicts involving smaller groups are within larger communities. The overall image that emerges, therefore, is that conflicts and disputes only occur between communities, nations, and specially organized groups, a situation which is not fully correct, as far as the occurrence of conflict is concerned. This study looked at a unique situation of conflict between Nyaribari and Kitutu who share the same origin, history and cultural values yet have been engaged in conflict since the 19th century. The purpose of this study was to trace the history of the Sweta Clan and relationship between Nyaribari and Kitutu sub-clans. Examine the nature, source and impact of the disputes among the Sweta at Keroka town and its environ, which www.ijirk.com 57 | P a g e International Journal of Innovative Research and Knowledge ISSN-2213-1356 forms the boundary between the two groups and discuss the strategies employed to cope with conflicts and disputes between the two parties. -

National Assembly

October 5, 2016 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES 1 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL REPORT Wednesday, 5th October, 2016 The House met at 9.30 a.m. [The Deputy Speaker (Hon. (Dr.) Laboso) in the Chair] PRAYERS QUORUM Hon. Deputy Speaker: Can we have the Quorum Bell rung? (The Quorum Bell was rung) Hon. Deputy Speaker: Okay Members. Let us settle down. We are now ready to start. We have a Petition by Hon. Njuki. POINT OF ORDER PETITION ON ALLEGED MISAPPROPRIATION OF FUNDS BY THE KENYA SWIMMING FEDERATION Hon. Njuki: Thank you, Hon. Deputy Speaker for giving me the opportunity this morning to air my sentiment on the issue of petitions. According to Standing Order No.227 on the committal of petitions, a petition is supposed to take, at least, 60 days to be dealt with by a Committee. Hon. Deputy Speaker: Hon. Njuki, I am just wondering whether whatever you are raising was approved or not. Hon. Njuki: Hon. Deputy Speaker, I do not have a petition. I just have a concern about a petition I brought to this House on 12th November, 2015. It touches on a very serious issue. It is a petition on the alleged mismanagement and misappropriation of funds by the Kenya Swimming Federation. That was in November 2015. This Petition has not been looked into. Considering what happened during the Rio de Janeiro Olympics, there were complaints about the Federation taking people who were not qualified to be in the swimming team. To date nothing has happened. I know the Committee is very busy and I do not deny that, but taking a whole year to look at a petition when the Standing Orders say it should be looked into in 60 days is not right. -

Changing Kenya's Literary Landscape

CHANGING KENYA’S LITERARY LANDSCAPE CHANGING KENYA’S LITERARY LANDSCAPE Part 2: Past, Present & Future A research paper by Alex Nderitu (www.AlexanderNderitu.com) 09/07/2014 Nairobi, Kenya 1 CHANGING KENYA’S LITERARY LANDSCAPE Contents: 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 4 2. Writers in Politics ........................................................................................................ 6 3. A Brief Look at Swahili Literature ....................................................................... 70 - A Taste of Culture - Origins of Kiswahili Lit - Modern Times - The Case for Kiswahili as Africa’s Lingua Franca - Africa the Beautiful 4. JEREMIAH’S WATERS: Why Are So Many Writers Drunkards? ................ 89 5. On Writing ................................................................................................................... 97 - The Greats - The Plot Thickens - Crime & Punishment - Kenyan Scribes 6. Scribbling Rivalry: Writing Families ............................................................... 122 7. Crazy Like a Fox: Humour Writing ................................................................... 128 8. HIGHER LEARNING: Do Universities Kill by Degrees? .............................. 154 - The River Between - Killing Creativity/Entreprenuership - The Importance of Education - Knife to a Gunfight - The Storytelling Gift - The Colour Purple - The Importance of Editors - The Kids are Alright - Kidneys for the King -

The Kenya General Election

AAFFRRIICCAA NNOOTTEESS Number 14 January 2003 The Kenya General Election: senior ministerial positions from 1963 to 1991; new Minister December 27, 2002 of Education George Saitoti and Foreign Minister Kalonzo Musyoka are also experienced hands; and the new David Throup administration includes several able technocrats who have held “shadow ministerial positions.” The new government will be The Kenya African National Union (KANU), which has ruled more self-confident and less suspicious of the United States Kenya since independence in December 1963, suffered a than was the Moi regime. Several members know the United disastrous defeat in the country’s general election on December States well, and most of them recognize the crucial role that it 27, 2002, winning less than one-third of the seats in the new has played in sustaining both opposition political parties and National Assembly. The National Alliance Rainbow Coalition Kenyan civil society over the last decade. (NARC), which brought together the former ethnically based opposition parties with dissidents from KANU only in The new Kibaki government will be as reliable an ally of the October, emerged with a secure overall majority, winning no United States in the war against terrorism as President Moi’s, fewer than 126 seats, while the former ruling party won only and a more active and constructive partner in NEPAD and 63. Mwai Kibaki, leader of the Democratic Party (DP) and of bilateral economic discussions. It will continue the former the NARC opposition coalition, was sworn in as Kenya’s third government’s valuable mediating role in the Sudanese peace president on December 30. -

The Kenya Gazette

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaperat the G.P.O.) Vol. CXV_No.68 NAIROBI, 3rd May, 2013 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE No. 6117 THE ELECTIONS ACT (No. 24 of 2011) THE ELECTIONS (PARLIAMENTARY AND COUNTY ELECTIONS) PETITION RULES, 2013 THE ELECTION PETITIONS,2013 IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 75 of the Elections Act and Rule 6 of the Elections (Parliamentary and County Elections) Petition Rules, 2013, the Chief Justice of the Republic of Kenya directs that the election petitions whose details are given hereunder shall be heard in the election courts comprising of the judges and magistrates listed andsitting at the court stations indicated in the schedule below. SCHEDULE No. Election Petition Petitioner(s) Respondent(s) Electoral Area Election Court Court Station No. BUNGOMA SENATOR Bungoma High Musikari Nazi Kombo Moses Masika Wetangula Senator, Bungoma County| Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition IEBC Muthuku Gikonyo No. 3 of 2013 Madahana Mbayah MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT Bungoma High Moses Wanjala IEBC Memberof Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Lukoye Bernard Alfred Wekesa Webuye East Muthuku Gikonyo No. 2 of 2013 Sambu Constituency, Bungoma Joyce Wamalwa, County Returning Officer Bungoma High John Murumba Chikati| LE.B.C Memberof Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Returning Officer Tongaren Constituency, Muthuku Gikonyo No. 4 of 2013 Eseli Simiyu Bungoma County Bungoma High Philip Mukui Wasike James Lusweti Mukwe Memberof Parliament, Justice Hellen A. Bungoma Court Petition IEBC Kabuchai Constituency, Omondi No. 5 of 2013 Silas Rotich Bungoma County Bungoma High Joash Wamangoli IEBC Memberof Parliament, Justice Hellen A. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: DR. RACHEL WANJIRU KAMAU-KANG’ETHE KENYATTA UNIVERSITY, DEPARTMENT OF EARLY CHILDHOOD STUDIES EDUCATION, P.O. BOX, 43844, NAIROBI. KENYA. DATE OF BIRTH: 20TH MAY, 1953. RELIGION: PROTESTANT, P.C.E.A. Toll-Ruiru FAMILY STATUS: THREE CHILDREN, 29, 28, 23. EMAIL ADDRESS: rachel.kamau368@gmail TELEPHONE: MOBILE +254 718722747 +254724622883 OFFICE 8109101 EX. 573537 EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: December, 2004: Doctor of Philosophy in Special Needs Education Topic: “A Study of Measures Used to Identify Gifted and Talented Children in Two Provinces of Kenya” Sept. 1986-1989: Master of Arts Degree in Special Education (Learning Disabled, Gifted and Talented) Ontario Institute for Studies in Education; University of Toronto - Canada. 1980-1982: Master of Education in Special Education (Education for the Visually Impaired and the Mentally Retarded) Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, U.S.A. 1992-1994: Diploma in Neuropsychology - Niilo Maki Institute, University of Jyvaskyla - Finland. 1974-1977: Bachelor of Education (History, Philosophy and Religious Studies). - University of Nairobi (Kenyatta University College), Kenya. 1 1972-1973: East African Advanced Certificate of Education (History, Literature and Divinity) Loreto High School, Limuru. 1968-1971: East African Certificate of Education - Kambui Girls' High School. 1961-1967: Kenya Certificate of Primary Education - Kambui Primary School. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: 1989-1990: Tutorial Fellow, Kenyatta University, Department of Educational Psychology 1991 - 1995: Lecturer: Department of Educational Psychology 1989-1995: Lectured in Educational Psychology Courses *Introduction to Psychology *Human Growth and Development *Educational Psychology 1995-2001: - Lecturer: Department of Educational Psychology. (Special Needs Education Section). - Participated in the development of Bachelor of Education (Special Needs Education) Degree Programme. -

Country Report 2Nd Quarter 1998 © the Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1998

COUNTRY REPORT Kenya 2nd quarter 1998 The Economist Intelligence Unit 15 Regent Street, London SW1Y 4LR United Kingdom The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit is a specialist publisher serving companies establishing and managing operations across national borders. For over 50 years it has been a source of information on business developments, economic and political trends, government regulations and corporate practice worldwide. The EIU delivers its information in four ways: through subscription products ranging from newsletters to annual reference works; through specific research reports, whether for general release or for particular clients; through electronic publishing; and by organising conferences and roundtables. The firm is a member of The Economist Group. London New York Hong Kong The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit 15 Regent Street The Economist Building 25/F, Dah Sing Financial Centre London 111 West 57th Street 108 Gloucester Road SW1Y 4LR New York Wanchai United Kingdom NY 10019, US Hong Kong Tel: (44.171) 830 1000 Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Tel: (852) 2802 7288 Fax: (44.171) 499 9767 Fax: (1.212) 586 1181/2 Fax: (852) 2802 7638 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.eiu.com Electronic delivery EIU Electronic Publishing New York: Lou Celi or Lisa Hennessey Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Fax: (1.212) 586 0248 London: Jeremy Eagle Tel: (44.171) 830 1007 Fax: (44.171) 830 1023 This publication is available on the following electronic and other media: Online databases Microfilm FT Profile (UK) NewsEdge Corporation (US) World Microfilms Publications (UK) Tel: (44.171) 825 8000 Tel: (1.781) 229 3000 Tel: (44.171) 266 2202 DIALOG (US) Tel: (1.415) 254 7000 CD-ROM LEXIS-NEXIS (US) The Dialog Corporation (US) Tel: (1.800) 227 4908 SilverPlatter (US) M.A.I.D/Profound (UK) Tel: (44.171) 930 6900 Copyright © 1998 The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. -

Al-Shabaab and Political Volatility in Kenya

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs EVIDENCE REPORT No 130 IDSAddressing and Mitigating Violence Tangled Ties: Al-Shabaab and Political Volatility in Kenya Jeremy Lind, Patrick Mutahi and Marjoke Oosterom April 2015 The IDS programme on Strengthening Evidence-based Policy works across seven key themes. Each theme works with partner institutions to co-construct policy-relevant knowledge and engage in policy-influencing processes. This material has been developed under the Addressing and Mitigating Violence theme. The material has been funded by UK aid from the UK Government, however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies. AG Level 2 Output ID: 74 TANGLED TIES: AL-SHABAAB AND POLITICAL VOLATILITY IN KENYA Jeremy Lind, Patrick Mutahi and Marjoke Oosterom April 2015 This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are clearly credited. First published by the Institute of Development Studies in April 2015 © Institute of Development Studies 2015 IDS is a charitable company limited by guarantee and registered in England (No. 877338). Contents Abbreviations 2 Acknowledgements 3 Executive summary 4 1 Introduction 6 2 Seeing like a state: review of Kenya’s relations with Somalia and its Somali population 8 2.1 The North Eastern Province 8 2.2 Eastleigh 10 2.3