Machu Picchu.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F.!F.F AREQUIPA - PER No Ej

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE SAN AGUSTÍN DE AREQUIPA FACULTAD DE GEOLOGÍA, GEOFÍSICA Y MINAS ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE INGENIERÍA GEOLÓGICA "GEOLOGÍA, PROFUNDIZACIÓN Y PROYECTO DE EXPLORACIÓN DE LA VETA MIRTHA" COMPAÑIA DE MINAS BUENAVENTURA S.A.A. DISTRITO DE TAPAY, PROVINCIA DE CAYLLOMA Y DEPARTAMENTO DE AREQUIPA" TESIS PRESENTADA POR EL BACHILLER: ALEX SAUL CALAPUJA CONDORI PARA OPTAR EL TITULO PROFESIONAL DE: INGENIERO GEOLOGO. UNSA- SAOI No. Doc ...fl:?.: .. !f:.f..:f.!f.f_ AREQUIPA - PER No Ej. __________ QL.~ .. f.~fhª!.-E? .13../.U2•. 2014 Firma Registrador. ....... ....... .. ... -......... DEDICATORIA A Dios, por concederme la dicha de la vida y todo lo que soy, por brindarme la sabiduría y el conocimiento de su palabra. Con todo mi cariño y amor, por inculcarme sus valores y sabios consejos en todo momento, a mi queridos padres Braulio y Juana. A mi adorable esposa Beatriz, por su apoyo incondicional y a mi hijo por su fuerza y energía, el que me hizo comprender lo maravilloso que es la vida de ser padre A mis queridos hermanos: Hilda, Wilber, Braulio y Ruby; Gracias por su paciencia y amor. AGRADECIMIENTOS El estudio de tesis titulado: " Geología, Profundización y proyecto de exploración de la Veta Mirtha en el proyecto Tambomayo" Distrito TAPA Y Provincia CA YLLOMA, Departamento AREQUIP A", no habría sido posible sin el apoyo de Compañía de Minas Buenaventura S.A.A. Por ello, mi mayor agradecimiento al Presidente de Directorio Ing. Roque Benavides Gamoza y al Gerente General de Geología Mes Ing. Julio Meza Paredes, al Gerente General de Tambomayo Ing. Renzo Macher Carmelino, y al Superintendente de Geología Tambomayo Ing. -

Machu Picchu & the Sacred Valley

Machu Picchu & The Sacred Valley — Lima, Cusco, Machu Picchu, Sacred Valley of the Incas — TOUR DETAILS Machu Picchu & Highlights The Sacred Valley • Machu Picchu • Sacred Valley of the Incas • Price: $1,995 USD • Vistadome Train Ride, Andes Mountains • Discounts: • Ollantaytambo • 5% - Returning Volant Customer • Saqsaywaman • Duration: 9 days • Tambomachay • Date: Feb. 19-27, 2018 • Ruins of Moray • Difficulty: Easy • Urumbamba River • Aguas Calientes • Temple of the Sun and Qorikancha Inclusions • Cusco, 16th century Spanish Culture • All internal flights (while on tour) • Lima, Historic Old Town • All scheduled accommodations (2-3 star) • All scheduled meals Exclusions • Transportation throughout tour • International airfare (to and from Lima, Peru) • Airport transfers • Entrance fees to museums and other attractions • Machu Picchu entrance fee not listed in inclusions • Vistadome Train Ride, Peru Rail • Personal items: Laundry, shopping, etc. • Personal guide ITINERARY Machu Picchu & The Sacred Valley - 9 Days / 8 Nights Itinerary - DAY ACTIVITY LOCATION - MEALS Lima, Peru • Arrive: Jorge Chavez International Airport (LIM), Lima, Peru 1 • Transfer to hotel • Miraflores and Pacific coast Dinner Lima, Peru • Tour Lima’s Historic District 2 • San Francisco Monastery & Catacombs, Plaza Mayor, Lima Cathedral, Government Palace Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner Ollyantaytambo, Sacred Valley • Morning flight to Cusco, The Sacred Valley of the Incas 3 • Inca ruins: Saqsaywaman, Rodadero, Puca Pucara, Tambomachay, Pisac • Overnight: Ollantaytambo, Sacred -

Travel Manual

Travel Manual 2017-2018 Confidential Rates ECS TRAVEL Your one-stop Travel Supplier for Peru 1 Welcome Thanks for your interest in working with ECS Travel. Since 2001, ECS Travel has been a leading full-service Tour Operator specialized in providing high quality customized tours that cover all Peru’s unique destinations: Cusco, Machu Picchu, Lake Titicaca, Nasca Lines, The Amazon, Lima and other highlights. We are a fully licensed Inca Trail Operator, we can guarantee your clients’ Inca Trail permits, and thanks to our local bilingual Guides and crew of native Quechua Porters we can provide you with only the best memorable experiences for your clients. Your clients will receive full attention to detail in every step of their travel experience. From the moment, they touch down at Lima International Airport until they board their flight to return home, you can be assured that they are in our safe and knowledgeable hands. 2 Contents ➢ Hiking Tours ➢ Classic Tours ➢ Tour Extensions ➢ Airport/Hotel Transfer services ➢ Hotels ➢ How to Book ➢ Terms and Conditions 3 INDEX Welcome ...................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Contents ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 I) Hiking Tours ........................................................................................................................................................... -

PROJECT REPORT MACHU PICCHU SANCTUARY VOLUNTEER TRIP November 2-11, 2016

PROJECT REPORT MACHU PICCHU SANCTUARY VOLUNTEER TRIP November 2-11, 2016 Figure 1. November 2016 ConservationVIP Volunteers on terraces overlooking the Urubamba River Executive Summary Conservation Volunteers International Program (ConservationVIP) organized and led a volunteer trip to the Historical Sanctuary of Machu Picchu in November 2016, in collaboration with Peru’s Ministry of Culture, and the Ministry of Environment (National Service for Protected Area Management, SERNANP). The project was authorized by Doctor Vidal Pino Zambrano, Director de la Direccion Desconcentrada de Cultura Cusco - Ministry of Culture, and by engineer José Carlos Nieto Navarrete, Jefe of the Historical Sanctuary of Machu Picchu for SERNANP. The projects were discussed with anthropologist José Fernando Astete Victoria, Jefe del Parque Arqueológico Nacional de Machupicchu. Twenty volunteers, including the two trip leaders, John Hollinrake and Dr. Bill Sapp, ConservationVIP Board Members, and el Licenciado Santiago Carrasco Bellota, performed 500 hours of volunteer work related to the following projects: Machu Picchu November 2016 Volunteer Trip Report Page 2 1. On Sunday, November 6, 2017, volunteers cleared Melinis minutiflora, known colloquially as pasto gordura, from 1.35 kilometers of Inca Trail between the Guard House and the Sun Gate, from 0.16 kilometers of the 50-steps portion of the Inca Trail between Wiñay Wayna and the Sun Gate, and from an approximately 1 meter buffer on either side of the trail. Total area cleared of approximately 5,205 square meters. One group of volunteers dug 35 holes for planting native trees along the trail. 2. On Monday, November 7, 2017, one group of volunteers cleared Melinis minutiflora from 750 sq. -

The Amazon River Without Secrets

Geographic Society of Lima Jr. Puno 450, Lima; post office box 100-1176 Lima, Peru; phone (511) 4273723; (511) 4269930 e-mail: [email protected]; http://socgeolima.org Press Release THE AMAZON RIVER WITHOUT SECRETS Geographic Society of Lima resolves controversial hypotheses concerning the source of the Queen of all Rivers The mystery concerning the sources of the Amazon River, similar to the one concerning those of the Nile, has long been subject to never-ending speculations and academic disputes. The identification of the main river’s source section poses many difficulties for researchers, as all the hydrological criteria are rarely met at the same time. In the case of such a vast hydrographical system and such an important water artery as the Amazon River, the complications increase even more. Hydrologists believe that the stream which runs the most water, which is the longest, and who’s source lies highest above the sea level should be considered the main river. Equally important are criteria concerning the riverbed gradient, the basin activity or the morphology of the terrain. Also, the importance of culture is unquestionable. Sometimes the traditions preserved through history and the culture of a region are arguments influencing the choice of the main river. Since the time of Humboldt, the Marañón has been considered the source tributary of the Amazon River. In 1934 the geodesist Colonel Gerardo Dianderas formulated the insight that it would rather be the Ucayali as it is longer, of higher importance to the history of the region, navigable to a greater extend, and as it plays a more important economic role. -

Memoria Anual 2013

MINISTERIO DE CULTURA MEMORIA ANUAL 2013 INDICE PRESENTACIÓN I. INTRODUCCIÓN I.1 La Cultura I.2 Breve historia del Ministerio I.3 El Marco normativo II. PANORAMA GENERAL II.1 Cultura en el Perú, sus condicionantes II.2 A dónde queremos ir II.3 Ejes de la Política Cultural III. ALTA DIRECCIÓN III.1 Las relaciones con el Legislativo III.2 Presencia en el país III.3 Representando al Perú en el Mundo IV. PATRIMONIO CULTURAL MATERIAL E INMATERIAL IV.1 La milenaria herencia andina IV.2 Los aportes coloniales y republicanos IV.3 Cerámica, tejidos y pinturas en vitrina IV.4 Lenguas, tradiciones y costumbres IV.5 Valorando el paisaje cultural IV.6 Cultura peruana en el mundo IV.7 Defensa del patrimonio Cultural V. INDUSTRIAS CULTURALES V.1 Audiovisual, fonografía y los nuevos medios V.2 Libro y lectura VI. CREACIÓN CULTURAL Y ARTES VIVAS VI.1 Alentando la creación artística VI.2 Difundiendo cultura VII. PERÚ, MULTICULTURAL Y MULTIÉTNICO VIII. PRESENCIA DEL MINISTERIO EN LAS REGIONES IX. SOPORTE DE LA GESTIÓN IX.1 Organización IX.2 Avances institucionales IX.3 Estados Financieros PRESENTACIÓN La presente Memoria describe los avances realizados por el Ministerio de Cultura en el año. Resaltamos la continuidad del trabajo institucional, pese a que el período fue cubierto por dos gestiones. Con improntas lógicamente diferenciadas, ambos equipos de trabajo contribuyeron al proceso de institucionalización de un Ministerio joven, permitiendo afrontar los desafíos de las áreas programáticas que la ley le asigna, tener voz en las máximas instancias de decisión política del país y hacer las coordinaciones intersectoriales que le corresponden por su rol rector en el campo de la cultura. -

Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ

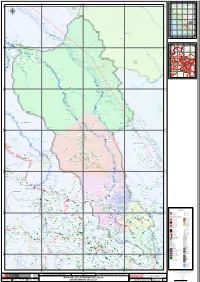

81° W 78° W 75° W 72° W 69° W 800000 820000 840000 ° ° 0 0 R 0 í 0 o 0 C 0 COLOMBIA a 0 l 0 l a n 0 0 ECUADOR Victoria g a 2 2 6 Sacramento Santuario 6 8 8 S S 560 Nacional ° ° Esmeralda Megantoni 3 3 TUMBES LORETO PIURA AMAZONAS S S ° ° R 6 LAMBAYEQUECAJAMARCA BRASIL 6 ío 565 M a µ e SAN MARTIN Quellouno st ró Trabajos n LA LIBERTAD Rosario S S Bellavista ° ° 9 ANCASH 9 HUANUCO UCAYALI 570 PASCO R Mesapata 1 ío P CUSCO a u c Monte Cirialo a Ocampo r JUNIN ta S S m CALLAOLIMA ° b ° o MADRE DE DIOS 2 2 1 Rí CUSCO 1 Paimanayoc o M ae strón HUANCAVELICA OCÉANO PACÍFICO Chaupimayo AYACUCHOAPURIMAC 575 ICA PUNO S S Mapitonoa ° ° Chaupichullo Lacco 1 5 5 Qosqopata Quellomayo 1 1 Emp. CU-104. Mameria AREQUIPA Llactapata MOQUEGUA Huaynapata Emp. CU-104. Miraflores MANU Alto Serpiyoc. BOLIVIA S S TACNA Cristo Salvador Achupallayoc ° Emp. CU-698 ° Larco 580 8 8 Emp. CU-104. 1 1 Quesquento Alto. Yanamayo CU Limonpata CU «¬701 81° W 78° W 75° W 72° W 69° W CU Campanayoc Alto Emp. CU-698 Chunchusmayo Ichiminea «¬695 Kcarun 693 Antimayo «¬ Dos De Mayo Santa Rosa Serpiyoc Cerpiyoc Serpiyoc Alto Mision Huaycco Martinesniyoc San Jose de Sirphiyoc Emp. CU-694 (Serpiyoc) CU Emp. CU-696 CU Cosireni Paititi Quimsacocha Emp. CU-105 (Chancamayo) 694 Limonpata Santa C¬ruz 698 Emp. CU-104 585 R « R ¬ « Emp. CU-104 (Lechemayo). í ío CU o U Ur ru ub 697 Emp. -

“El Señor De Viñaka: El Pongo De La Yunka”

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL MAYOR DE SAN MARCOS FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES UNIDAD DE POSGRADO “EL SEÑOR DE VIÑAKA: EL PONGO DE LA YUNKA” TESIS Para optar el grado académico de Magister en Antropología AUTOR Carmen Cazorla Zen ASESOR Ladislao Landa Vásquez Lima – Perú 2015 2IIII II “EL SEÑOR DE VIÑAKA; EL PONGO DE LA YUNKA” 3 III Para: Mayu, José Víctor y Gabriela Mis hermosos hijos 4 IV AGRADECIMIENTO A mi familia por el apoyo incondicional y el empuje para continuar con esta investigación. A los Kamayoq. Pedro Anyosa, Germán Carrera y Mariano Huillca, por sus testimonios tan importantes en la investigación. 5 V Contenido INTRODUCCION .............................................................................................................................. 9 CAPITULO I ..................................................................................................................................... 13 CONSIDERACIONES TEÓRICAS Y METODOLÓGICAS ...................................................... 13 1.1 Justificación ......................................................................................................................... 13 1.2 Algunos puntos de partida................................................................................................ 14 1.3 Problemática ......................................................................................................................... 16 1.4 Objetivo General ................................................................................................................ -

Lista De Proyectos Validados Como Aptos En El Marco Del Primer Concurso De Proyectos 2020

ANEXO N° 01: LISTA DE PROYECTOS VALIDADOS COMO APTOS EN EL MARCO DEL PRIMER CONCURSO DE PROYECTOS 2020 CÓDIGO DEL PROYECTO CÓDIGO ÚNICO DE ORGANISMO APORTE TOTAL DEL N° UNIDAD ZONAL DEPARTAMENTO PROVINCIA DISTRITO NOMBRE DEL PROYECTO EMPLEOS PROGRAMADOS ESTADO DE APTO VALIDACIÓN "TRABAJA PERÚ" INVERSIONES PROPONENTE PROGRAMA S/ MUNICIPALIDAD MEJORAMIENTO DEL SERVICIO DE TRANSITABILIDAD EN CALLES ALEDAÑAS AL PARQUE PRINCIPAL DE LA LOCALIDAD DE 1 AMAZONAS AMAZONAS CHACHAPOYAS MAGDALENA 3000000266 2208674 DISTRITAL DE 140,336.00 44 APTO VALIDADOS MAGDALENA, DISTRITO DE MAGDALENA - CHACHAPOYAS - AMAZONAS MAGDALENA MUNICIPALIDAD CREACION DE LA LOSA DEPORTIVA EN LA CC.NN. KAWIT, SECTOR MARAÑON, DISTRITO DE NIEVA - PROVINCIA DE CONDORCANQUI - 2 AMAZONAS AMAZONAS CONDORCANQUI NIEVA 3000000384 2456840 PROVINCIAL DE 125,211.00 33 APTO VALIDADOS DEPARTAMENTO DE AMAZONAS CONDORCANQUI MUNICIPALIDAD CREACION DE LA LOSA DEPORTIVA EN LA CC.NN. ALTO KUIT, SECTOR DOMINGUSA, DISTRITO DE NIEVA - PROVINCIA DE 3 AMAZONAS AMAZONAS CONDORCANQUI NIEVA 3000000399 2456949 PROVINCIAL DE 124,271.00 32 APTO VALIDADOS CONDORCANQUI - DEPARTAMENTO DE AMAZONAS CONDORCANQUI CREACION DE ESCALINATAS DEL ANEXO DE COLLACRUZ DISTRITO DE LEVANTO - PROVINCIA DE CHACHAPOYAS - DEPARTAMENTO DE MUNICIPALIDAD 4 AMAZONAS AMAZONAS CHACHAPOYAS LEVANTO 3000000352 2468179 160,703.00 42 APTO VALIDADOS AMAZONAS DISTRITAL DE LEVANTO MUNICIPALIDAD CREACION DE LA LOSA DEPORTIVA EN LA CC.NN. NUEVO KUIT, SECTOR DOMINGUSA, DISTRITO DE NIEVA - PROVINCIA DE 5 AMAZONAS AMAZONAS CONDORCANQUI NIEVA 3000000391 2456978 PROVINCIAL DE 127,105.00 33 APTO VALIDADOS CONDORCANQUI - DEPARTAMENTO DE AMAZONAS CONDORCANQUI MUNICIPALIDAD CREACION DE LOSA DEPORTIVA EN LA CC.NN. JEMPETS, SECTOR DOMINGUSA, DISTRITO DE NIEVA - PROVINCIA DE CONDORCANQUI - 6 AMAZONAS AMAZONAS CONDORCANQUI NIEVA 3000000383 2456976 PROVINCIAL DE 126,437.00 33 APTO VALIDADOS DEPARTAMENTO DE AMAZONAS CONDORCANQUI MUNICIPALIDAD CREACION DE LA LOSA DEPORTIVA EN LA CC.NN. -

CBD First National Report

BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN PERU __________________________________________________________ LIMA-PERU NATIONAL REPORT December 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................ 6 1 PROPOSED PROGRESS REPORT MATRIX............................................... 20 I INTRODUCTION......................................................................................... 29 II BACKGROUND.......................................................................................... 31 a Status and trends of knowledge, conservation and use of biodiversity. ..................................................................................................... 31 b. Direct (proximal) and indirect (ultimate) threats to biodiversity and its management ......................................................................................... 36 c. The value of diversity in terms of conservation and sustainable use.................................................................................................................... 47 d. Legal & political framework for the conservation and use of biodiversity ...................................................................................................... 51 e. Institutional responsibilities and capacities................................................. 58 III NATIONAL GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ON THE CONSERVATION AND SUSTAINABLE USE OF BIODIVERSITY.............................................................................................. 77 -

ICAHM Final Program

FINAL CONFERENCE PROGRAM EL PROGRAMA FINAL DEL CONGRESO WITH PAPER ABTRACTS/CON LOS RESUMENES 27-30 NOVEMBER/NOVIEMBRE, 2012 CUZCO, PERU THANK YOU TO OUR HOSTS GRACIAS A NUESTROS ANFITRIONES UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL SAN ANTONIO ABAD DEL CUSCO 1 Monday, November 26 Inauguración en la Municipalidad del Cuzco Words from: Mayor of Cuzco: Economista Luis Florez García Rector of the National University of Cuzco: Dr. Germán Zecenarro Madueño Drs. Douglas Comer and Willem Willems, Co-Presidents of ICAHM Dr. Alberto Martorell, President of ICOMOS-PERU Musical performance: Sylvia Falcón Welcome Cocktail Party in the Museo Machu Picchu, Casa Concha Words from: Dr. Jean-Jacques Decoster, Director of the Museo Machu Picchu Tuesday, November 27 9:00-10:30 Participants pick up their registration materials at Municipalidad del Cuzco 10:30-12:30 KEYNOTE TALKS LOCATION: MUNICIPALIDAD DEL CUZCO MODERATOR: WILLEM WILLEMS 10:30 Doug Comer (Co-President, ICAHM) 11:00 Fritz Lüth (President, European Association of Archaeologists) 11:30 Ruth Shady (Former President, ICOMOS-Peru) 12:00 Nuria Sanz (UNESCO) (read by Willem Willems) 12:30 -2:30 LUNCH BREAK 2:30-5:15 Management and Policy LOCATION: MUNICIPALIDAD DEL CUZCO MODERATOR: HELAINE SILVERMAN 2:30-2:45 Neale Draper: “Managing Archaeological Heritage in the Pilbara Resources Boom” 2:45-3:00 Elin Dalen: “Cultural and Natural Heritage-A New Policy for World Heritage in Norway” 3:00-3:15 Alejandro Camino Diez Canseco: “Making Heritage sites conservation sustainable: the experience of the Global Heritage Fund” 3:15-3:30 -

Mathematics and Architecture of the Incas in Peru

AC 2011-2240: MATHEMATICS AND ARCHITECTURE OF THE INCAS IN PERU Cheri Shakiban, University of St. Thomas I am a professor of mathematics at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, where I have been a faculty member since 1983. I received my Ph.D. in 1979 from Brown University in Formal Cal- culus of Variations. My recent area of research is mostly in computer vision, with applications to object recognition. My publications are in diverse areas of mathematics and engineering. I love to work with undergraduate students, in particular, underrepresented students, to get them involved in doing research in mathematics and encourage them to give conference presentations/posters and submit their work for publication. In addition to teaching regular math courses, I also like to create and teach innovative courses such as ”Mathematical symmetry of Southern Spain” and ”Mathematics and Architecture of the Incas in Peru”, which I have taught as study abroad courses several times. Michael P. Hennessey, University of St. Thomas Michael P. Hennessey (Mike) joined the full-time faculty as an Assistant Professor fall semester 2000. He is an expert in machine design, computer-aided-engineering, and in the kinematics, dynamics, and control of mechanical systems, along with related areas of applied mathematics. Presently, he has published 41 technical papers (published or accepted), in journals (9), conferences (31), or magazines (1). In 2006 he was tenured and promoted to the rank of Associate Professor. Mike gained 10 years of industrial and academic research lab experience at 3M, FMC, and the University of Minnesota prior to embarking on an academic career at Rochester Institute of Technology (3 years) and Minnesota State University, Mankato (2 years).