Fair Courts: Setting Recusal Standards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iron County Heads to Polls Today

Mostly cloudy High: 49 | Low: 32 | Details, page 2 DAILY GLOBE yourdailyglobe.com Tuesday, April 4, 2017 75 cents Iron County TURKEY STRUT heads to polls today By RICHARD JENKINS sor, three candidates — incum- [email protected] bent Jeff Stenberg, Tom Thomp- HURLEY — Iron County vot- son Jr. and James Schmidt — ers head to the polls today in a will be vying for two town super- series of state and local races. visor seats. Mercer Clerk Chris- At the state level, voters will tan Brandt and Treasurer Lin decide between incumbent Tony Miller are running unopposed. Evers and Lowell Holtz to see There is also a seat open on who will be the state’s next the Mercer Sanitary Board, how- superintendent of public instruc- ever no one has filed papers to tion. Annette Ziegler is running appear on the ballot. unopposed for another term as a The city of Montreal also has justice on the Wisconsin two seats up for election. In Supreme Court. Ward 1, Joan Levra is running Iron County Circuit Court unopposed to replace Brian Liv- Judge Patrick Madden is also ingston on the council, while running unopposed for another Leola Maslanka is being chal- term on the bench. lenged by Bill Stutz for her seat Iron County’s local municipal- representing Ward 2. ities also have races on the ballot The other town races, all of — including contested races in which feature unopposed candi- Kimball, Mercer and Montreal. dates, are as follows: In Kimball, Town Chairman —Anderson: Edward Brandis Ron Ahonen is being challenged is running for chairman, while by Joe Simonich. -

National Association of Women Judges Counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3

national association of women judges counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Poverty’s Impact on the Administration of Justice / 1 President’s Message / 2 Executive Director’s Message / 3 Cambridge 2012 Midyear Meeting and Leadership Conference / 6 MEET ME IN MIAMI: NAWJ 2012 Annual Conference / 8 District News / 10 Immigration Programs News / 20 Membership Moments / 20 Women in Prison Report / 21 Louisiana Women in Prison / 21 Maryland Women in Prison / 23 NAWJ District 14 Director Judge Diana Becton and Contra Costa County native Christopher Darden with local high school youth New York Women in Prison / 24 participants in their November, 2011 Color of Justice program. Read more on their program in District 14 News. Learn about Color of Justice in creator Judge Brenda Loftin’s account on page 33. Educating the Courts and Others About Sexual Violence in Unexpected Areas / 28 NAWJ Judicial Selection Committee Supports Gender Equity in Selection of Judges / 29 POVERTY’S IMPACT ON THE ADMINISTRATION Newark Conference Perspective / 30 OF JUSTICE 1 Ten Years of the Color of Justice / 33 By the Honorable Anna Blackburne-Rigsby and Ashley Thomas Jeffrey Groton Remembered / 34 “The opposite of poverty is justice.”2 These words have stayed with me since I first heard them Program Spotlight: MentorJet / 35 during journalist Bill Moyers’ interview with civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson. In observance News from the ABA: Addressing Language of the anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, they were discussing what Dr. Access / 38 King would think of the United States today in the fight against inequality and injustice. -

September 2009 • Vol

43085-1 AlaBar:Layout 1 9/21/09 2:16 PM Page 313 SEPTEMBER 2009 • VOL. 70, NO. 5 2009-10 ASBASB PresidentPresident ThomasThomas J.J. MethvinMethvin andand FamilyFamily CelebrateCelebrate ProPro BonoBono WeekWeek OctoberOctober 25-31,25-31, 20092009 43085-1 AlaBar:Layout 1 9/21/09 2:16 PM Page 314 43085-1 AlaBar:Layout 1 9/22/09 2:51 PM Page 315 43085-1 AlaBar:Layout 1 9/21/09 2:16 PM Page 316 43085-1 AlaBar:Layout 1 9/21/09 2:16 PM Page 317 On the SEPTEMBER 2009 • VOL. 70, NO. 5 Cover In This Issue ASB President Thomas J. Methvin and family—Pictured are Amy and Tom Methvin, center, and their two sons, 334 ASB Spring 2009 Admittees Rucker, left, and Slade, right. Tom and Amy met when he was in law ASB LEADERSHIP FORUM: school at Cumberland and have been 338 Update and General Selection Criteria married for over 18 years. Their children By Sam David Knight attend St. James School in Montgomery, 340 where Rucker is in the 11th grade and on Class 5 Graduates the basketball team, and 8th-grader Slade 341 A Perspective on the ASB’s 2009 Leadership Forum–Class 5 is on the football and basketball teams. By Lisa Darnley Cooper –Photo by Kenneth Boone Photography 344 2009 ASB Annual Meeting Awards and Highlights 350 Celebrate Alabama’s Pro Bono Week Departments By Phil D. Mitchell 319 President’s Page Access to Justice– 352 Alabama Law Foundation Announces Now More than Ever Kids’ Chance Scholarship Recipients 321 Executive 353 State Bar LRS Offers Discounts to Military Personnel Director’s Report Rendering Service to Those 354 Outside the Courtroom and Inside the Classroom: from Another Continent Career Attorney Discovers Joy of Teaching 325 Memorials By Kimberly L. -

2010 April Montana Lawyer

April 2010 THE MONTANA Volume 35, No. 6 awyerTHE STATE BAR OF MONTANA SpecialL issue on Montana courts Tweeting Supreme Court docket is now a major viewable to all on the web trial Developments in the 2 biggest UM’s discipline cases student The trouble Grace Case with money in Project changes judicial elections the landscape for media coverage Chopping down the backlog Changes in procedures at the Supreme Court cuts the deficit Ethics opinion on the new in the caseload notary rule THE MONTANA LAWYER APRIL INDEX Published every month except January and July by the State Bar of Montana, 7 W. Sixth Ave., Suite 2B, P.O. Box 577, Helena MT 59624. Phone (406) 442-7660; Fax (406) 442-7763. Cover Story E-mail: [email protected] UM’s Grace Case Project: trial coverage via Internet 6 STATE BAR OFFICERS President Cynthia K. Smith, Missoula President-Elect Features Joseph Sullivan, Great Falls Secretary-Treasurer Ethics Opinion: notary-rule compliance 12 K. Paul Stahl, Helena Immediate Past President Money floods campaigns for judgeships 22 Chris Tweeten, Helena Chair of the Board Shane Vannatta, Missoula Commentary Board of Trustees Pam Bailey, Billings President’s Message: Unsung heroes 4 Pamela Bucy, Helena Darcy Crum, Great Falls Op-Ed: A nation of do-it-yourself lawyers 25 Vicki W. Dunaway, Billings Jason Holden, Great Falls Thomas Keegan, Helena Jane Mersen, Bozeman State Bar News Olivia Norlin, Glendive Mark D. Parker, Billings Ryan Rusche, Wolf Point Lawyers needed to aid military personnel 14 Ann Shea, Butte Randall Snyder, Bigfork Local attorneys and Law Day events 15 Bruce Spencer, Helena Matthew Thiel, Missoula State Bar Calendar 15 Shane Vannatta, Missoula Lynda White, Bozeman Tammy Wyatt-Shaw, Missoula Courts ABA Delegate Damon L. -

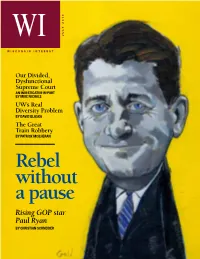

Rebel Without a Pause Rising GOP Star Paul Ryan by Christian Schneider Editor > Charles J

WI 2010 JULY WISCONSIN INTEREST Our Divided, Dysfunctional Supreme Court AN INVESTIGATIVE REPORT BY MIKE NICHOLS UW’s Real Diversity Problem BY DAVID BLASKA The Great Train Robbery BY PATRICK MCILHERAN Rebel without a pause Rising GOP star Paul Ryan BY CHRISTIAN SCHNEIDER Editor > CHARLES J. SYKES Hard choices WI WISCONSIN INTEREST For a rising political star, Paul Ryan remains a nation’s foremost celebrity wonk, asking: remarkably lonely political figure. For years, “What’s so damn special about Paul Ryan?” under both Democrats and Republicans, he More than his matinee-idol looks. has warned about the need to avert a fiscal “Ryan is a throwback,” writes Schneider, Publisher: meltdown, but even though his detailed “he could easily have been a conservative Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, Inc. “Roadmap” for restraining government politician in the era before cable news. He spending was widely praised, it was embraced has risen to national stardom by taking the Editor: Charles J. Sykes by very few. path least traveled by modern politicians: He Despite lip-service praise from President knows a lot of stuff.” Managing Editor: Marc Eisen Obama, Democrats have launched serial Also in this issue, Mike Nichols examines Art Direction: attacks against the plan, while GOP leaders Wisconsin’s dysfunctional, divided Supreme Stephan & Brady, Inc. have made themselves scarce, avoiding being Court and the implications for law in the state. Contributors: yoked to the specificity of Ryan’s hard choices. Patrick McIlheran deconstructs the state’s David Blaska But Ryan’s warnings have taken on new signature boondoggle, the billion-dollar not- Richard Esenberg urgency as Europe’s debt crisis unfolds, and so-fast train from Milwaukee to somewhere Patrick McIlheran the U.S. -

Studzr 2/2006

_St_u_dz_·R________________________________________________ セRセQMセ_PセPV@ 285 Dr. Mattbias S. Fifka::· Party and Ioterest Group Involvement in U.S. Judicial Elections Abstract In 2004, a race for a seat on the Illinois Supreme Court cost $ 9.3 million, which exceeded the cxpenditurcs made in 18 U.S. Senate races in the same year. Overall, candidates for state Supreme Courts spent $47 million on their campaigns in 2004, and parties and interest groups invested another $ 12 million to influence the electoral outcome. In the following paper it is argued that judicial elections in thc United Statcs havc bccomc incrcasing- ly similar to political elections and that money is a crucial determinant for winning a judicial election. It is also argued that the increasing dependence of judges on campaign contributions severely endangers judicial impartia- lity. When making decisions on the bench judges now more than ever not \ only have to take into consideration the facts presented, but also the will of their supporters. ::- Dr. Matthias S. Fzfka is assistant professor for American and Interna- tional Politics at the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürn- berg. He has published numerous articles and books on interest groups and the political process in the United States. 2/2006 286 sセエセエエ、セzセrセMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM I. Introduction Th mere idea of "judicial elections" may sound somewhat odd to the European ear be:,.tUse it is uncommon in the Old World that judges are elcctcd dircctly by the citi- . ns. Even in Great Britain, whose common-law systemwas one of the foundations コセ@ American legal system was built upon, judges are appointed by authorities, in セョセウエ@ cascs the Queen hcrsclf. -

Honorable Nathan L. Hecht Chief Justice of Texas PRESIDENT-ELECT

Last Revised June 2021 PRESIDENT: Honorable Nathan L. Hecht Chief Justice of Texas PRESIDENT-ELECT: Honorable Paul A. Suttell Chief Justice of Rhode Island ALABAMA ARKANSAS Honorable Tom Parker Honorable John Dan Kemp Chief Justice Chief Justice Alabama Supreme Court Supreme Court of Arkansas 300 Dexter Avenue Justice Building Montgomery, AL 36104-3741 625 Marshall St. (334) 229-0600 FAX (334) 229-0535 Little Rock, AR 72201 (501) 682-6873 FAX (501) 683-4006 ALASKA CALIFORNIA Honorable Joel H. Bolger Chief Justice Honorable Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye Alaska Supreme Court Chief Justice 303 K Street, 5th Floor Supreme Court of California Anchorage, AK 99501 350 McAllister Street (907) 264-0633 FAX (907) 264-0632 San Francisco, CA 94102 (415) 865-7060 FAX (415) 865-7181 AMERICAN SAMOA COLORADO Honorable F. Michael Kruse Chief Justice Honorable Brian D. Boatright The High Court of American Samoa Chief Justice Courthouse, P.O. Box 309 Colorado Supreme Court Pago Pago, AS 96799 2 East 14th Avenue 011 (684) 633-1410 FAX 011 (684) 633-1318 Denver, CO 80203-2116 (720) 625-5410 FAX (720) 271-6124 ARIZONA CONNECTICUT Honorable Robert M. Brutinel Chief Justice Honorable Richard A. Robinson Arizona Supreme Court Chief Justice 1501 W. Washington Street, Suite 433 State of Connecticut Supreme Court Phoenix, AZ 85007-3222 231 Capitol Avenue (602) 452-3531 FAX (602) 452-3917 Hartford, CT 06106 (860) 757-2113 FAX (860) 757-2214 1 Last Revised June 2021 DELAWARE HAWAII Honorable Collins J. Seitz, Jr. Honorable Mark E. Recktenwald Chief Justice Chief Justice Supreme Court of Delaware Supreme Court of Hawaii The Renaissance Centre 417 South King Street 405 N. -

Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court

2011 Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court Prepared by: WISCONSIN CIVIL JUSTICE COUNCIL, INC. JANUARY 2011 2011 Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court By Andrew Cook and Jim Hough The Hamilton Consulting Group, LLC January 2011 The Wisconsin Civil Justice Council, Inc. (WCJC) was formed in early 2009 to represent Wisconsin business interests on civil litigation issues before the Legislature and courts. Our goal is to achieve fairness and equity, reduce costs, and enhance Wisconsin‘s image as a place to live and work. The Wisconsin Civil Justice Council Board is proud to present its first biennial Judicial Evaluation of the Wisconsin Supreme Court. The purpose of the Judicial Evaluation is to educate WCJC‘s members and the public by providing a summary of the most important decisions issued by the Court which have had an effect on Wisconsin business interests. Officers and Board Members President - Bill Smith Vice President - James Buchen National Federation of Independent Business Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce Treasurer-Andy Franken Secretary - Pat Stevens Wisconsin Insurance Alliance Wisconsin Builders Association John Mielke James Boullion Associated Builder & Contractors Associated General Contractors of Wisconsin Michael Crooks Beata Kalies Wisconsin Defense Counsel Electric Cooperatives Gary Manke Nickolas George Midwest Equipment Dealers Association Midwest Food Processors Association Mary Ann Gerrard Peter Thillman Wisconsin Automobile & Truck Dealers Assn. Wisconsin Economic Development Assn. Eric Borgerding Mark Grapentine -

The Third Branch, Summer 2002

Vol 10 No 3 H I G H L I G H T S Summer 2 Court financing to be studied 7 Volunteers in the Courts 2002 4 Eau Claire launches restorative justice 10 Wisconsin judges help to reform Chinese courts program 12 Three new judges take the bench 6 Sesquicentennial projects planned 14 People Budget reform act Truth-in-Sentencing, part II means cuts for courts by Judge Michael B. Brennan, Milwaukee County Circuit Court by Deborah Salm, budget officer n 1998, the Wisconsin Legislature 2, page 18). The MR converter was n July 26, Governor Scott Ipassed, and the governor signed into chosen to maintain consistency in the OMcCallum signed into law 2001 law, 1997 Act 283, which brought maximum time an inmate can serve in Act 109, the budget reform act. The act Truth-in-Sentencing to our state for prison prior to first release. After took effect on July 30. McCallum intro- crimes committed on and after Dec. 31, applying the MR converter to initially place a crime in one of the new A-I duced the budget reform bill in 1999. The act provided the basic structure for determinate sentencing, but classes, the CPSC made adjustments so February in order to address an esti- a publication of the Wisconsin Judiciary a publication of the Wisconsin none of the details. Parole was abolished that crimes of similar severity are mated $1.1 billion deficit in the state's and felony sentences were restructured classified together. The exact placement general fund during the 2001-2003 bien- as bifurcated sentences consisting of a of each crime is discussed in the nium. -

2018 State Supreme Court Elections

2018 State Supreme Court Elections For real-time tracking of TV spending in this year’s state supreme court races, see the Brennan Center’s Buying Time. For data from candidate state campaign finance filings, see the National Institute on Money in Politics. Date of # of # of Date of General Type of Seats Contested # Of Names of Primary Election Names of General Election State Primary Election Election Available Seats Candidates Candidates Candidates Chief Justice Position: Chief Justice Position: Bob Vance Jr., Democrat Tom Parker, Republican Lyn Stewart, Republican* Bob Vance Jr., Democrat Tom Parker, Republican Place 1: Place 1: Sarah Hicks Stewart, Debra Jones, Republican Republican Brad Mendheim, Republican* Place 2: Sarah Hicks Stewart, Tommy Bryan, Republican* Republican Place 3: Place 4: Will Sellers, Republican* Donna Wesson Smalley, Place 4: Democrat Donna Wesson Smalley, John Bahakel, Republican Democrat Alabama 6/5/18 11/6/18 Partisan 5 3 11 Jay Mitchell, Republican Jay Mitchell, Republican General: David Sterling (advanced to 5/22/18 runoff) Kenneth Hixson Runoff: Courtney Goodson* Arkansas N/A 11/6/18 Nonpartisan 1 1 3 N/A (advanced to runoff) Harold D. Melton* John Ellington Michael P. Boggs* Nels Peterson* Georgia N/A 5/22/18 Nonpartisan 5 0 5 N/A Britt Cagle Grant* *—Incumbent Gray—Uncontested general election for all seats Green —Election has passed Bold—Winner Date of # of # of Date of General Type of Seats Contested # Of Names of Primary Election Names of General Election State Primary Election Election Available Seats Candidates Candidates Candidates Idaho 5/15/18 N/A Nonpartisan 1 0 1 G. -

August 6, 2020 Honorable Nathan L. Hecht President, Conference Of

August 6, 2020 Honorable Nathan L. Hecht President, Conference of Chief Justices c/o Association and Conference Services 300 Newport Avenue Williamsburg, VA 23185-4147 RE: Bar Examinations and Lawyer Licensing During the COVID-19 Pandemic Dear Chief Justice Hecht: On behalf of the American Bar Association (ABA), the largest voluntary association of lawyers and legal professionals in the world, I write to urge the Conference of Chief Justices (CCJ) to prioritize the development of a national strategy for bar examinations and lawyer licensing for the thousands of men and women graduating law school during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a temporary change and only as necessary to address the public health and safety issues presented during this crisis without closing the doors to our shared profession. In particular, we recommend that this national strategy urge each jurisdiction to cancel in-person bar examinations during the pandemic unless they can be administered in a safe manner; establish temporary measures to expeditiously license recent law school graduates and other bar applicants; and enact certain practices with respect to the administration of remote bar examinations. We appreciate that some jurisdictions may have already taken some action, such as modifying the bar examination dates or setting or temporarily modifying their admission or practice rules. But the failure of all jurisdictions to take appropriate action presents a crisis for the future of the legal profession that will only cascade into future years. Earlier this week, the ABA House of Delegates discussed this important subject and heard from many different stakeholders within the legal profession, including concerns from the National Conference of Bar Examiners. -

State Bar of Wisconsin Statement on New Chief Justice

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 14, 2021 State Bar of Wisconsin Statement on New Chief Justice KATHLEEN BROST, President, State Bar of Wisconsin LARRY J. MARTIN, Executive Director, State Bar of Wisconsin Madison, WI – The State Bar of Wisconsin welcomes Chief Justice Annette Ziegler as she begins her term as leader of the Wisconsin court system. We look forward to her leadership and continuing to work with all seven justices to further our common goal of strengthening the relationship between the bench and the bar, advancing public trust of the legal profession, and promoting a high-functioning justice system. We also extend our sincere thanks and gratitude to Chief Justice Patience Roggensack for her leadership during her three terms. In particular, Chief Justice Roggensack led the court system through the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic to keep it operational and justice moving forward. We also want to thank her for her advocacy in advancing research to ensure best practices are implemented including the use of business courts, and treatment courts across Wisconsin. We look forward to working with her in the years to come. ### The State Bar of Wisconsin is an integrated professional association, created by the Wisconsin Supreme Court, for attorneys who hold a Wisconsin law license. With more than 25,000 members, the State Bar aids the courts in improving the administration of justice, provides continuing legal education for its members to help them maintain their expertise, and assists Wisconsin lawyers in carrying out community service initiatives to educate the public about the legal system and the value of lawyers.