Thematic Evaluation of MYHF in Ethiopia Formative Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Somali Region

Federalism and ethnic conflict in Ethiopia. A comparative study of the Somali and Benishangul-Gumuz regions Adegehe, A.K. Citation Adegehe, A. K. (2009, June 11). Federalism and ethnic conflict in Ethiopia. A comparative study of the Somali and Benishangul-Gumuz regions. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13839 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13839 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 8 Inter-regional Conflicts: Somali Region 8.1 Introduction The previous chapter examined intra-regional conflicts within the Benishangul-Gumuz region. This and the next chapter (chapter 9) deal with inter-regional conflicts between the study regions and their neighbours. The federal restructuring carried out by dismantling the old unitary structure of the country led to territorial and boundary disputes. Unlike the older federations created by the union of independent units, which among other things have stable boundaries, creating a federation through federal restructuring leads to controversies and in some cases to violent conflicts. In the Ethiopian case, violent conflicts accompany the process of intra-federal boundary making. Inter-regional boundaries that divide the Somali region from its neighbours (Oromia and Afar) are ill defined and there are violent conflicts along these borders. In some cases, resource conflicts involving Somali, Afar and Oromo clans transformed into more protracted boundary and territorial conflicts. As will be discussed in this chapter, inter-regional boundary making also led to the re-examination of ethnic identity. -

OCHA Weekly Humanitarian Bulletin

Weekly Humanitarian Bulletin Ethiopia 27 June 2017 Following poor performing spring rains, the number of people receiving humanitarian assistance has increased from 5.6 million to 7.8 million in the first quarter of the year, and is expected to heighten further in the second half of the year. Increased funding is needed Key Issues urgently, in particular to address immediate requirements for food and nutrition, as well as clean drinking water, much of which is being delivered long distances by truck as regular The Fall wells have dried up. Armyworm infestation Fall Armyworm threaten to destroy up to 2 million hectares of meher crops across Ethiopia continues to The Fall Armyworm infestation destroy meher continues to destroy meher crops crops across 233 across 233 woredas in six regions, woredas in six and it is spreading at an alarming regions, and it is rate. The pest has already affected spreading at an more than 145,000 hectares of alarming rate. maize cropland, mostly in traditionally surplus producing and First quarter densely populated areas. With the Therapeutic current pace, up to 2 million Feeding Program hectares of meher cropland are at admissions risk, leading to between 3 to 4 exceeded HRD million metric tons of grain loss. projections. The implication of this loss is multi- layered, impacting household food The number of security and national grain reserve irregular Ethiopian as well as potentially impacting migrants returning grain exports. from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia The Government, with support from (KSA) has the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and other partners, is taking several measures to reached 35,000 curb the spread of the infestations, but the need exceeds the ongoing response. -

Hum Ethio Manitar Opia Rian Re Espons E Fund D

Hum anitarian Response Fund Ethiopia OCHA, 2011 OCHA, 2011 Annual Report 2011 Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Humanitarian Response Fund – Ethiopia Annual Report 2011 Table of Contents Note from the Humanitarian Coordinator ................................................................................................ 2 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 2011 Humanitarian Context ........................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Map - 2011 HRF Supported Projects ............................................................................................. 6 2. Information on Contributors ................................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Donor Contributions to HRF .......................................................................................................... 7 3. Fund Overview .................................................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Summary of HRF Allocations in 2011 ............................................................................................ 8 3.1.1 HRF Allocation by Sector ....................................................................................................... -

The Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation Steering Group

Humanitarian Bulletin Ethiopia Issue #17| 23 Sept – 06 Oct. 2019 In this issue Ethiopia drought response evaluation P.1 Flooding in Gambella and Somali P.2 Fighting climate change P.2 Hope in the midst of crisis P.5 HIGHLIGHTS Humanitarian funding update P. 6 • On 30 September and on 3 October 2019, the inter- agency humanitarian evaluation steering group presented its evaluation findings on the drought response in The Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation Ethiopia (2015- 2018) to members Steering Group Presented its Evaluation of the Ethiopia Humanitarian Findings on the 2015-2018 Drought Response in Country Team (EHCT). Ethiopia • Based on the On 30 September and on 3 October 2019, the inter-agency humanitarian evaluation steering survey findings, the group presented its evaluation findings on the drought response in Ethiopia (2015-2018) to group put forth five members of the Ethiopia Humanitarian Country Team (EHCT). key Some of the major findings of the survey include, 1) while the drought responses were recommendation. effective in many respects, key lessons from past similar surveys were not learnt and implemented. Hence, findings and recommendations continued to be similar over the years; 2) the needs assessments were weak and there was weak formal accountability to affected population; 3) there was sufficient early warning information available, but it did not lead to enough early action in terms of preventing negative effects of the droughts such as on livelihood; 4) there was little success in restoring livelihoods and strengthening resilience; 5) the responses were well coordinated, with some remaining space for improvement, including the fact that there were few national NGOs accessing funding and partaking in the responses and the need for improvement in the coordination between clusters and for enhanced strategic decision making in the EHCT forums. -

Measles Outbreak Investigation and Response in Jarar Zone of Ethiopian Somali Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia

International Journal of Microbiological Research 8 (3): 86-91, 2017 ISSN 2079-2093 © IDOSI Publications, 2017 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.ijmr.2017.86.91 Measles Outbreak Investigation and Response in Jarar Zone of Ethiopian Somali Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia 12Yusuf Mohammed and Ayalew Niguse 1Ethiopian Somali Regional Health Bureau, Jigjiga, P.O. Box: 238, Jigjiga, Ethiopia 2Department of Microbiology and Public Health, Jigjiga University, P.O. Box: 1020, Jigjiga, Ethiopia Abstract: Suspected measles outbreak was notified from Degahbour hospital to the Emergency Management Team at the Regional Health Bureau. A team of experts was dispatched to the site with the objectives of confirming the existence of the outbreak, initiate measures and formulate recommendations based on the results of present outbreak investigation. We conducted descriptive cross sectional study from February to March 2016. We reviewed medical records of suspected cases; we interviewed the Health care workers, visited affected household and interviewed parents and guardians of cases. We used line list for describing measles cases interms of time, place and person. We collected five blood samples from patients for Lab confirmation. We entered and analyzed using Epi-Info7 version 7.1.0.6. During the investigation period, 406 measles cases with 5 deaths were reported with overall Attack Rate (AR) and Case Fatality Rate (CFR) was (28.2/10, 000 population, 1.2%) respectively. High AR (28.6/10000population) was reported from male. The CFR difference was not statistically significant (P value=0.66) by sex. High AR (127/10000population) was reported from age group < 1 years. When we compared AR by those < 5 years and >5 years, there was statistically significant difference (P-value= 0.00). -

Systematic Review Article the Impacts of El-Niño-Southern Oscillation

Systematic Review Article The Impacts of El-Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on Agriculture and Coping Strategies in Rural Communities of Ethiopia ABSTRACT The principal cause of drought in Ethiopia is asserted to be the fluctuation of the global atmospheric circulation, which is triggered by Sea Surface Temperature Anomaly (SSTA), occurring due to El Niño- Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events. It can make extreme weather events more likely in certain regions in Ethiopia. ENSO episodes and events, and related weather events have an impact on seasonal rainfall distribution and rainfall variability over Ethiopia. Thus, the main aim of this review was to identify and organize the major impacts of El-Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on agriculture and adaptation strategies of rural communities in Ethiopia. Most of the rural communities in the country depend on rain- fed agriculture, and millions of Ethiopians have lost their source of food, water, and livelihoods due to drought triggered by ENSO. The coping strategies against ENSO induced climate change are creating a collective risk analysis, and Climate-Resilient Green Economy (CRGE) at the national level. In addition, community-based coping strategies for ENSO are integrated with watershed management, livelihood diversification and land rehabilitation to better cope with erratic rainfall and drought risks in the country. Key words: El-Niño-Southern Oscillation, drought, coping strategies, Ethiopia 1. INTRODUCTION The evidence for climate variability or change is certain, and its impacts are already being felt globally [1]. Climate variability associated with El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a climactic event which has significant impacts on agricultural production, food security and rural livelihoods in many parts of the world [2]. -

Agency Deyr/Karan 2012 Seasonal

Food Supply Prospects FOR THE YEAR 2013 ______________________________________________________________________________ Disaster Risk Management and Food Security Sector (DRMFSS) Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) March 2013 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Table of Contents Glossary ................................................................................................................. 2 Acronyms ............................................................................................................... 3 EXCUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 11 REGIONAL SUMMARY OF FOOD SUPPLY PROSPECT ............................................. 14 SOMALI ............................................................................................................. 14 OROMIA ........................................................................................................... 21 TIGRAY .............................................................................................................. 27 AMHARA ........................................................................................................... 31 AFAR ................................................................................................................. 34 BENISHANGUL GUMUZ ..................................................................................... 37 SNNP ............................................................................................................... -

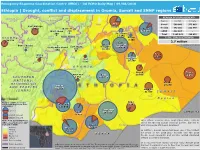

Drought, Conflict and Displacement in Oromia, Somali and SNNP Regions

Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) – DG ECHO Daily Map | 09/08/2018 Ethiopia | Drought, conflict and displacement in Oromia, Somali and SNNP regions REASON OF DISPLACEMENT* BENSHANGUL- GUMAZ AMAHARA Region Conflict Climate AFAR Siti Somali 500 003 373 663 East Wallega 78 687 Oromia 643 201 112 949 27 672 North Sheva Fafan West Sheva 220 113 593 SNNP 822 187 - 309 Dire Dawa Total 1 965 391 486 612 11 950 Kelem Wellega Harari TOTAL IDPs In ETHIOPIA 24 338 3 605 East 2.7 million West Bunno Bedele Hararghe *Excluding other causes East Sheva Hararghe 2 172 South West Sheva 169 860 180 678 40 030 Jimma Jarar 5 448 49 007 Arsi Erer zone SOMALIA 4 185 36 308 Source: Fews Net OROMIA Nogob Doolo West Arsi Bale 25 659 89 911 S O U T H E R N 4 454 121 772 NATIONS, Korahe NATIONALITIES 24 295 Gedeo A N D PEOPLES 822 187 (SNNP) Shabelle SOUTH 41 536 S O M A L I SUDAN R e g i o n Number of IDPs in Oromia Afder and Somali Region per Zone West Guji 55 963 (July 2018) 147 040 20 000 Dawa zone Guji 244 638 SOMALIA Conflict induced 51 682 Climate induced Source: Fews Net, IOM Acute Food Insecurity Phase Inter-ethnic violence since September 2017, namely DTM Round 11 | Source (IPC’s classification for July– along the Oromia-Somali regional border, has led to for Gedeo and West Guji: September 2018) Liben 500 000 people still being displaced. IOM Situation Report N.1 No Data 114 069 Borena 4-18 July 2018 Minimal 156 110 In addition, Somali region has been one of the hardest Stressed hit areas of the 2016-2017 drought and the 2018 Crisis KENYA floods. -

Somali Region: Multi – Agency Deyr/Karan 2012 Seasonal Assessment Report

SOMALI REGION: MULTI – AGENCY DEYR/KARAN 2012 SEASONAL ASSESSMENT REPORT REGION Somali Regional State November 24 – December 18, 2012 DATE ASSESSMENT STARTED & COMPLETED TEAM MEMBERS – Regional analysis and report NAME AGENCY Ahmed Abdirahman{Ali-eed} SCI Ahmed Mohamed FAO Adawe Warsame UNICEF Teyib Sheriff Nur FAO Mahado Kasim UNICEF Mohamed Mohamud WFP Name of the Agencies Participated Deyr 2012 Need Assessment Government Bureaus DRMFSS, DPPB,RWB,LCRDB,REB,RHB,PCDP UN – WFP,UNICEF,OCHA,FAO,WHO Organization INGO SCI,MC,ADRA,IRC,CHF,OXFAMGB,Intermon Oxfam, IR,SOS,MSFH,ACF LNGO HCS,OWDA,UNISOD,DAAD,ADHOC,SAAD,KRDA 1: BACKGROUND Somali Region is one of largest regions of Ethiopia. The region comprises of nine administrative zones which in terms of livelihoods are categorised into 17 livelihood zones. The climate is mostly arid/semi-arid in lowland areas and cooler/wetter in the higher areas. Annual rainfall ranges from 150 - ~600mm per year. The region can be divided into two broader rainfall regimes based on the seasons of the year: Siti and Fafan zones to the north, and the remaining seven zones to the south. The rainfall pattern for both is bimodal but the timings differ slightly. The southern seven zones (Nogob, Jarar, Korahe, Doollo, Shabelle, Afder, Liban and Harshin District of Fafan Zone) receive ‘Gu’ rains (main season) from mid April to end of June, and secondary rains known as ‘Deyr’ from early October to late December. In the north, Siti and Fafan zones excluding Harshin of Fafan zone receive ‘Dirra’ - Objectives of the assessment also known as ‘Gu’ rains from late March To evaluate the outcome of the Deyr/Karan to late May. -

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: the Political Situation

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: The political situation Conducted 16 September 2019 to 20 September 2019 Published 10 February 2020 This project is partly funded by the EU Asylum, Migration Contentsand Integration Fund. Making management of migration flows more efficient across the European Union. Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 Background ............................................................................................................ 5 Purpose of the mission ........................................................................................... 5 Report’s structure ................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 6 Identification of sources .......................................................................................... 6 Arranging and conducting interviews ...................................................................... 6 Notes of interviews/meetings .................................................................................. 7 List of abbreviations ................................................................................................ 8 Executive summary .................................................................................................. 9 Synthesis of notes ................................................................................................ -

Ethiopia: Administrative Map (August 2017)

Ethiopia: Administrative map (August 2017) ERITREA National capital P Erob Tahtay Adiyabo Regional capital Gulomekeda Laelay Adiyabo Mereb Leke Ahferom Red Sea Humera Adigrat ! ! Dalul ! Adwa Ganta Afeshum Aksum Saesie Tsaedaemba Shire Indasilase ! Zonal Capital ! North West TigrayTahtay KoraroTahtay Maychew Eastern Tigray Kafta Humera Laelay Maychew Werei Leke TIGRAY Asgede Tsimbila Central Tigray Hawzen Medebay Zana Koneba Naeder Adet Berahile Region boundary Atsbi Wenberta Western Tigray Kelete Awelallo Welkait Kola Temben Tselemti Degua Temben Mekele Zone boundary Tanqua Abergele P Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Tsegede Tselemt Mekele Town Special Enderta Afdera Addi Arekay South East Ab Ala Tsegede Mirab Armacho Beyeda Woreda boundary Debark Erebti SUDAN Hintalo Wejirat Saharti Samre Tach Armacho Abergele Sanja ! Dabat Janamora Megale Bidu Alaje Sahla Addis Ababa Ziquala Maychew ! Wegera Metema Lay Armacho Wag Himra Endamehoni Raya Azebo North Gondar Gonder ! Sekota Teru Afar Chilga Southern Tigray Gonder City Adm. Yalo East Belesa Ofla West Belesa Kurri Dehana Dembia Gonder Zuria Alamata Gaz Gibla Zone 4 (Fantana Rasu ) Elidar Amhara Gelegu Quara ! Takusa Ebenat Gulina Bugna Awra Libo Kemkem Kobo Gidan Lasta Benishangul Gumuz North Wello AFAR Alfa Zone 1(Awsi Rasu) Debre Tabor Ewa ! Fogera Farta Lay Gayint Semera Meket Guba Lafto DPubti DJIBOUTI Jawi South Gondar Dire Dawa Semen Achefer East Esite Chifra Bahir Dar Wadla Delanta Habru Asayita P Tach Gayint ! Bahir Dar City Adm. Aysaita Guba AMHARA Dera Ambasel Debub Achefer Bahirdar Zuria Dawunt Worebabu Gambela Dangura West Esite Gulf of Aden Mecha Adaa'r Mile Pawe Special Simada Thehulederie Kutaber Dangila Yilmana Densa Afambo Mekdela Tenta Awi Dessie Bati Hulet Ej Enese ! Hareri Sayint Dessie City Adm.