A Beginning Guide to Acting While Singing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History T-0001 Interviewees: Chick Finney and Martin Luther Mackay Interviewer: Irene Cortinovis Jazzman Project April 6, 1971

ORAL HISTORY T-0001 INTERVIEWEES: CHICK FINNEY AND MARTIN LUTHER MACKAY INTERVIEWER: IRENE CORTINOVIS JAZZMAN PROJECT APRIL 6, 1971 This transcript is a part of the Oral History Collection (S0829), available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Today is April 6, 1971 and this is Irene Cortinovis of the Archives of the University of Missouri. I have with me today Mr. Chick Finney and Mr. Martin L. MacKay who have agreed to make a tape recording with me for our Oral History Section. They are musicians from St. Louis of long standing and we are going to talk today about their early lives and also about their experiences on the music scene in St. Louis. CORTINOVIS: First, I'll ask you a few questions, gentlemen. Did you ever play on any of the Mississippi riverboats, the J.S, The St. Paul or the President? FINNEY: I never did play on any of those name boats, any of those that you just named, Mrs. Cortinovis, but I was a member of the St. Louis Crackerjacks and we played on kind of an unknown boat that went down the river to Cincinnati and parts of Kentucky. But I just can't think of the name of the boat, because it was a small boat. Do you need the name of the boat? CORTINOVIS: No. I don't need the name of the boat. FINNEY: Mrs. Cortinovis, this is Martin McKay who is a name drummer who played with all the big bands from Count Basie to Duke Ellington. -

Senior Focus: Mary Ann Erickson

Vol. 21 No. 3 • Fall 2016 www.tclifelong.org Senior Circle www.tompkinscounty.org/cofa A circle is a group of people in which everyone has a front seat. same time, we are still challenged Senior Focus: Mary Ann Erickson by many of the same issues that Gerontologist and the New Board President of Lifelong aging humans have always faced like declines in health and losses in our social network. I think it’s sometimes hard for us Baby Mary Ann Erickson became the new President of was a pivotal time for me, as I was Boomers to walk the line between the Board of Lifelong at the end of May. Recently involved with this research at every overconfident optimism about aging we had the opportunity to ask her a few questions stage, from developing the interview and unwarranted pessimism. We about her connection to Lifelong and her interest instrument to entering and using the need to prepare for both the in gerontology. data. I did some of the interviews possibilities and the challenges.” for this study, some of which I This is Mary Ann’s sixth year on the board having Any advice for the sandwich been recommended by colleagues from Ithaca remember quite clearly more than 10 years later. I used the Retirement generation? “Most of my peers are College’s Gerontology Institute. Mary Ann is an in this group, caring both for and Well-Being Study data for my Mary Ann Erickson, Associate Professor and Chair, Gerontology children and for aging dissertation.” Lifelong Board President Faculty, Planned Studies Program. -

View of the Related Literature

72-4684 WALLDREN, Allan Wade, 1934- THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN INSTRUMENT TO ANALYZE STUDENT QUESTIONS DURING PROBLEM SOLVING. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Education, general University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Allan Wade Walldren 1971 THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN INSTRUMENT TO ANALYZE STUDENT QUESTIONS DURING PROBLEM SOLVING DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Allan Wade Walldren, B.S., M.A.T * * it it it The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by ’~”1 Adviser Faculty■ of Curriculu and Foundations PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages have indistinct p rin t. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As author of this study I wish to publicly acknowledge and thank several people for their assistance, guidance and support in this investigation. First and foremost is Louise, my wife, who shared equally in all of the rigors and frustra tions of this investigation. She has been sounding board and colleague, critical editor and typist, and most of all an understanding and sensitive friend. I also wish to acknowledge Dr. Charles M. Galloway, who not only supported the study and assisted in its design, but also encouraged me to bring my past experiences into a new focus and to report them in a style that was comfortable. Dr. Paul R. Klohr not only supported the study but sensitively encouraged the investigator at the most appro priate times. Constructive criticism was always blended with a twinkle of humor. Both the study and the investigator were significantly strengthened by Dr. -

06.22.21 Approved Minutes

MINUTES OF THE BUCKSKIN FIRE DEPARTMENT DISTRICT FIRE BOARD 06/22/21-Open Meeting: Minutes to be approved at open public meeting on Tuesday, 07/20/2021. A Budget Workshop and Public Hearing of the Buckskin Fire Board convened on June 22, 2021, that started at 6:00 pm in the classroom of the Buckskin Fire District, located at: 8500 Riverside Drive, Parker, AZ 85344 that convened at 6:00 pm. The following matters were discussed at the Open Meeting Public Hearing 1. Call to Order: Budget Hearing open at 6:00 pm 2. Roll Call. Members Present: Chairman Jeff Daniel, Don Rountree, John Mihelich, Jeff McCormack, and Wayne Posey. Staff Present: Chief Maloney, Barbara Cole, Captain Weatherford, Captain Chambers, Lt. Fernandes, FF Maxwell, and FF Anderson. Public Present: Amanda Weatherford 3. (Discussion): Open to the Public for Comments. No Comments from the Public 4. Adjourn: Budget Hearing Closed: Public Budget Hearing closed at 6:02 pm Agenda Open Meeting 5. Convene into Open Meeting: 6:03 pm 6. Call to the Public. Consideration and discussion of comments from the public. Those wishing to address the Buckskin Fire District Board need not request permission in advance Pursuant to A.R.S. § 38-431.01(G), the Fire District Board is not permitted to discuss or take any action on items raised in the call to the public that is not specifically identified on the Agenda. However, individual Board members may be permitted to respond to criticism directed to them. Otherwise, the Board may direct that staff review the matter or ask that the matter be placed on a future agenda. -

August-September

Portland Peace Choir Newsletter Volume 2 No. 8, August/September 2017 PEAA VolunteCer Effort Eof the PoMrtland PeaEce ChoirAL TMhIeS PSoIOrtlNan Sd TPAeTacEe MChEoNir T strives to exemplify the principles of peace, Meet Our New equality, justice, It’s been an interesting summer for the stewardship of the Earth, DPortlainrd ePeace Cthooir, wr ith one change after unity and cooperation. another looming and forcing us out of our We sing music from comfort zone. We’re starting our new sea - diverse cultures and son off with a new director, in a new loca - traditions to inspire peace tion, and we will be singing music chosen in ourselves, our families, in a new way. our communities, and the world. We were all a bit uneasy about the prospect of finding a new director, but the search, interviewing, auditioning and selection processes all went surprisingly smoothly and we In This Issue were able to find a very talented and capable Director to lead us into the future with energy, optimism and enthusiasm. • Meet Our New Director! • Where In the World is the Kristin Gordon George is a musician, teacher, and the Artistic Di - rector of Resonate Choral Arts, an intergenerational womens’ choir. PPC? She also served as Music Director of the Metropolitan Community • Ready ... Set ... Sing! Church of Portland for nine years, where she directed the choir and • Beat the Heat band and arranged musical works for large group ensembles. She’s been writing music since childhood, and her repertoire now in - cludes contemporary songs, musical theater, cantatas and award- winning choral music. -

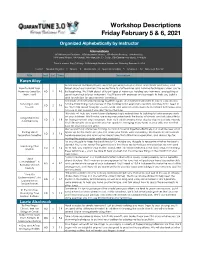

Workshop Descriptions Friday February 5 & 6, 2021

Workshop Descriptions Friday February 5 & 6, 2021 Organized Alphebetically by Instructor Abbreviations: HD=Hammered Dulcimer, MD=Mountain Dulcimer, BP=Bowed Psaltery, AH=Autoharp, PW=Penny Whistle, UK=Ukulele, MA=Mandolin, G= Guitar, CB+Clawhammer Banjo, FI=Fiddle Time is shown: Day (F=Friday, S=Saturday)-Session Number ex: Saturday Session 4 = S-4 Levels:1 = Absolute Beginner 2 = Novice 3 = Intermediate 4 = Upper Intermediate 5 = Advanced All = Non-Level Specific Title Inst. Lvl. Time Description Karen Alley As hammered dulcimer players, we often get wrapped up in notes and chords and tunes, and How to Hold Your forget about our hammers! The easiest time to start learning solid hammer technique is when you’re Hammers (and Use HD 1 F-3 first beginning. We’ll talk about different types of hammers, holding your hammers, and getting a Them, Too!) good sound out of your instrument. You’ll leave with exercises and concepts to help you build a solid foundation for your hammer technique. Someday soon we will be playing together again, and everyone will want to join in! Jam sessions Surviving a Jam can be intimidating if you’re new to the dulcimer (and even if you’re not!), but they don’t need to HD 2 F-4 Session be. We’ll talk about how jam sessions work, and work on simple melody and chord techniques you can use to join in even if you don’t know the tune. This class will help you move beyond playing single melody lines to building full solo arrangements on your dulcimer. -

Skain's Domain - Episode 13

Skain's Domain - Episode 13 Skain's Domain Episode 13 - June 22, 2020 0:00:00 Adam Meeks: Alright. Hey guys, thanks for joining us again this week. You're tuning into Skain's Domain with Wynton Marsalis, and I'm Adam Meeks your technical host for the evening. Tonight, we're joined by members of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra including Chris Crenshaw, Kenny Rampton, Elliot Mason, Camille Thurman, Ted Nash, Paul Nedzela, Walter Blanding, Dan Nimmer, and Carlos Henriquez. If you have a question you'd like to ask, we will have you use the raise hand feature. To do this, click participants on the bottom of your Zoom window, and then in the participants tab, press the raise hand button. Please also just make sure that your full name appears as your user name so we can call you when it's your turn. And before we do that, I'd like to hand the mic over to Mr. Wynton Marsalis to kick things off. Go ahead, Wynton. 0:00:47 Wynton Marsalis: Alright. Thank you very much, Adam. Welcome everybody back again this week for Skain's Domain where we discuss issues significant and trivial, and the more trivial they are, the more we... More impassioned we are about it. Today, I have the blessing of having the members of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. I missed them so much. And we spent so many times, so many years playing each other's music on bandstands. For our younger members, some started as students, for our older members, we've been here and I just wanna.. -

HENRY and LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL of MUSIC SPRING 2017 Fanfare

HENRY AND LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC SPRING 2017 fanfare 124488.indd 1 4/19/17 5:39 PM first chair A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN One sign of a school’s stature is the recognition received by its students and faculty. By that measure, in recent months the eminence of the Bienen School of Music has been repeatedly reaffirmed. For the first time in the history of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, this spring one of the contestants will be a Northwestern student. EunAe Lee, a doctoral student of James Giles, is one of only 30 pianists chosen from among 290 applicants worldwide for the prestigious competition. The 15th Van Cliburn takes place in May in Ft. Worth, Texas. Also in May, two cello students of Hans Jørgen Jensen will compete in the inaugural Queen Elisabeth Cello Competition in Brussels. Senior Brannon Cho and master’s student Sihao He are among the 70 elite cellists chosen to participate. Xuesha Hu, a master’s piano student of Alan Chow, won first prize in the eighth Bösendorfer and Yamaha USASU Inter national Piano Competition. In addition to receiving a $15,000 cash prize, Hu will perform with the Phoenix Symphony and will be presented in recital in New York City’s Merkin Concert Hall. Jason Rosenholtz-Witt, a doctoral candidate in musicology, was awarded a 2017 Northwestern Presidential Fellowship. Administered by the Graduate School, it is the University’s most prestigious fellowship for graduate students. Daniel Dehaan, a music composition doctoral student, has been named a 2016–17 Field Fellow by the University of Chicago. -

Name Music Department: Live Chat with Faculty and Students Hi Y’All, Thank You for Joining Us Today

Name Music Department: Live Chat with Faculty and Students Hi y’all, thank you for joining us today. We have Amy Dodds, Senior Lecturer of Music and Director of String Studies, Doug Scarborough, Associate Professor of Music, Jackie Wood, Senior Lecturer of Music and Director of Collaborative Piano, and WC: Madison Hollenbeck current student Yana Miakshyla '21 Hi, my name is Doug Scarborough. So nice to talk today to you all! I am the director of the top jazz band and jazz combos here at Whitman. I also enjoy teaching private lessons on trombone and improvisation, as well as classes in music theory, the Beatles, and songwriting. I believe strongly in helping students develop their creativity in music, whether that’s via improvisation, composition, or interpretation. I came to Whitman ten years ago from Mississippi, where I grew up immersed in the blues and R’ WC: Doug Scarborough n’B. Currently, the music I write blends jazz with Middle Eastern music Hello, everyone! Looking forward to hearing from you today. I organize all the string applied music, teach chamber music, music WC: Amy Dodds theory, and a course on women's compositions. Welcome! I am Jackie Wood and I teach piano and Collaborative Piano and play for Chamber Singers and Chorale! I've been at WC: Jackie Wood Whitman for about 30 years and love teaching students who represent every discipline at Whitman. Hi! My name is Yana Miakshyla. I am a rising senior (fourth-year student) majoring in Music (Standard track). I am also an WC: Yana Miakshyla '21 international student from Belarus. -

In Tune with MS

SUMMER 2014 www.narcoms.org Vol. 3, Issue 3 In Tune With MS GOLD GOLD AWARD WINNER a Summer 2014 NARCOMS NOW Congratulations to NARCOMS Now Photo Contest Summer 2014 Winner Joe M. — Columbus, OH “The Beat Goes On” What does the photo represent in your “MS Life”? “Live your passion.” — Joe M. A project of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers Summer 2014 / IN THIS ISSUE » 02 Letter from the Director: Summer’s Here with Country Music All-Stars 03 NARCOMS Info Corner 04 Feature Focus: Musicians Julie Roberts and Clay Walker 10 Survey 101: MS and Marijuana - A New Survey 12 MS Reflections: Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) 14 NARCOMS Messenger: World MS Day 2014 & NN Photo Contest 15 NARCOMS Snapshot: Early MS Symptoms 16 MS News: Medical Marijuana & MS, Birth Control Pills & Obesity 18 Q&A: NARCOMS results & “Old” Language on Surveys 19 New MS Apps & Blogs Feature 20 Play: Find the following words... 21 Faces of NARCOMS: Balancing the Tilt S T A F F Robert Fox, MD Ruth Ann Marrie, MD, PhD Gary R Cutter, PhD Managing Director Scientific Director Coordinating Center Director Stacey S Cofield, PhD Christina Crowe, MA Shawn Avery Stokes Executive Editor Managing Editor & Media Specialist Creative Director NARCOMS Now acknowledges and appreciates the companies listed below who have provided unrestricted educational grants through the Foundation of the CMSC toward production costs of NARCOMS Now, including printing and mailing. None of these companies have any control or influence over the content of NARCOMS Now and are not provided access to NARCOMS data in return for their support. -

Meet Singer-Songwriter Dana Countryman

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW Meet Singer-Songwriter Dana Countryman: Writing Songs in a Time-Warp In an age when most albums are Dana Countryman in his home re- slapped together like a poor excuse for a cording studio in Everett, Washington. hook (sandwiched between two pieces of Here, in this music and memento-filled cheap plywood), this album is an extraor- dinary accomplishment. Painstaking crafts- space, Countryman has recorded manship of both music and lyrics is what numerous albums over the past Dana is all about. To him, the song is every- decade-plus. thing. And it shows. The following interview was conducted long-distance, with me in Phoenix, Arizo- na, and Dana in his home studio in Everett, Washington, a suburb of Seattle. But it’s as intimate as if we were casually conversing in the same room. I do need to provide one disclaimer. I am the co-writer of one of the songs on Dana’s new album: “Then She Smiles.” But this in no way affects my journalistic objec- tivity regarding Dana. Even if you never listened to this one particular song, his new album would still be amazing. (Of course, I do hope you listen to all the tracks, because they are all worthy of your attention). (As an aside, I was quite honored when Dana asked me to work with him on the lyrics to his song. And I couldn’t be happi- er with the way the song turned out). So, Dana, tell me: what is “Vocal Retro Pop” all about, photo by Frank M. -

"If You're Reading This": Patriotic Themes in Country Music Between 2000-2010 Claire S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 From "courtesy of the red, white, and blue" to "if you're reading this": patriotic themes in country music between 2000-2010 Claire S. Carville Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Carville, Claire S., "From "courtesy of the red, white, and blue" to "if you're reading this": patriotic themes in country music between 2000-2010" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 3985. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3985 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM “COURTESY OF THE RED, WHITE, AND BLUE” TO “IF YOU’RE READING THIS”: PATRIOTIC THEMES IN COUNTRY MUSIC BETWEEN 2000-2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Mass Communication in The Manship School of Mass Communication by Claire Carville B.A., The University of Alabama, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my committee chair, Dr. Lisa Lundy, whose constant guidance, insight, and encouragement was appreciated every step of the writing process of this thesis. Next, thanks to committee member and fellow country music fan, Bob Mann, for being excited about this project from the very beginning.