WWC Single-Case Design Technical Documentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TUTORIAL in BIOSTATISTICS: the Self-Controlled Case Series Method

STATISTICS IN MEDICINE Statist. Med. 2005; 0:1–31 Prepared using simauth.cls [Version: 2002/09/18 v1.11] TUTORIAL IN BIOSTATISTICS: The self-controlled case series method Heather J. Whitaker1, C. Paddy Farrington1, Bart Spiessens2 and Patrick Musonda1 1 Department of Statistics, The Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK. 2 GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rue de l’Institut 89, B-1330 Rixensart, Belgium. SUMMARY The self-controlled case series method was developed to investigate associations between acute outcomes and transient exposures, using only data on cases, that is, on individuals who have experienced the outcome of interest. Inference is within individuals, and hence fixed covariates effects are implicitly controlled for within a proportional incidence framework. We describe the origins, assumptions, limitations, and uses of the method. The rationale for the model and the derivation of the likelihood are explained in detail using a worked example on vaccine safety. Code for fitting the model in the statistical package STATA is described. Two further vaccine safety data sets are used to illustrate a range of modelling issues and extensions of the basic model. Some brief pointers on the design of case series studies are provided. The data sets, STATA code, and further implementation details in SAS, GENSTAT and GLIM are available from an associated website. key words: case series; conditional likelihood; control; epidemiology; modelling; proportional incidence Copyright c 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 1. Introduction The self-controlled case series method, or case series method for short, provides an alternative to more established cohort or case-control methods for investigating the association between a time-varying exposure and an outcome event. -

Supplementary File

Supplementary file Table S1. Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review. Authors, reference Type of article Number of patients Type of stroke Valderrama [1] case report 1 AIS Oxley [2] case series 5 AIS Morassi [3] case series 6 AIS (n = 4), HS (n = 2) Tunc [4] case series 4 AIS Avula [5] case series 4 AIS (n = 3), TIA (n = 1) Oliver [6] case report 1 AIS Beyrouti [7] case series 6 AIS Al Saiegh [8] case series 2 AIS (n = 1), SAH (n = 1) Gunasekaran [9] case report 1 AIS Goldberg [10] case report 1 AIS Viguier [11] case report 1 AIS Escalard [12] case series/ case control 10 AIS Wang [13] case series 5 AIS Fara [14] case series 3 AIS Moshayedi [15] case report 1 AIS Deliwala [16] case report 1 AIS Sharafi-Razavi [17] case report 1 HS retrospective cohort study (case Jain [18] 35 AIS (n = 26) HS (n = 9) control) retrospective cohort study (case Yaghi [19] 32 AIS control) AIS (n = 35), TIA (n = 5), HS Benussi [20] retrospective cohort study 43 (n = 3) Rudilosso [21] case report 1 AIS Lodigiani [22] retrospective cohort study 9 AIS Malentacchi [23] case report 1 AIS J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, x; doi: FOR PEER REVIEW www.mdpi.com/journal/jcm J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, x FOR PEER REVIEW 2 of 8 retrospective cohort study/case Scullen [24] 2 HS + AIS (n = 1), AIS (n = 1) series retrospective cohort study/ case AIS (n = 17), ST (n = 2), HS Sweid [25] 22 series (n = 3) AIS – acute ischemic stroke; HS – haemorrhagic stroke; SAH – subarachnoid haemorrhage; ST – sinus thrombosis; TIA-transient ischemic attack. -

Case Series: COVID-19 Infection Causing New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus?

Endocrinology & Metabolism International Journal Case Series Open Access Case series: COVID-19 infection causing new-onset diabetes mellitus? Abstract Volume 9 Issue 1 - 2021 Objectives: This paper seeks to explore the hypothesis of the potential diabetogenic effect 1 2 of SARS-COV-2 (Severe Acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus). Rujuta Katkar, Narasa Raju Madam 1Consultant Endocrinologist at Yuma Regional Medical Center, Case series presentation: We present a case series of observation among 8 patients of age USA 2 group ranging from 34 to 74 years with a BMI range of 26.61 to 53.21 Kilogram/square Hospitalist at Yuma Regional Medical Center, USA meters that developed new-onset diabetes after COVID-19 infection. Correspondence: Rujuta Katkar, MD, Consultant Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-COV-2), commonly known as Endocrinologist at Yuma Regional Medical Center, 2851 S Coronavirus or COVID-19(Coronavirus infectious disease), gains entry into the cells by Avenue B, Bldg.20, Yuma, AZ-85364, USA, Tel 2034359976, binding to the Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2(ACE-2) receptors located in essential Email metabolic tissues including the pancreas, adipose tissue, small intestine, and kidneys. Received: March 25, 2021 | Published: April 02, 2021 The evidence reviewed from the scientific literature describes how ACE 2 receptors play a role in the pathogenesis of diabetes and the plausible interaction of SARS-COV-2 with ACE 2 receptors in metabolic organs and tissues. Conclusion: The 8 patients without a past medical history of diabetes admitted with COVID-19 infection developed new-onset diabetes mellitus due to plausible interaction of SARS-COV-2 with ACE 2 receptors. -

Observational Clinical Research

E REVIEW ARTICLE Clinical Research Methodology 2: Observational Clinical Research Daniel I. Sessler, MD, and Peter B. Imrey, PhD * † Case-control and cohort studies are invaluable research tools and provide the strongest fea- sible research designs for addressing some questions. Case-control studies usually involve retrospective data collection. Cohort studies can involve retrospective, ambidirectional, or prospective data collection. Observational studies are subject to errors attributable to selec- tion bias, confounding, measurement bias, and reverse causation—in addition to errors of chance. Confounding can be statistically controlled to the extent that potential factors are known and accurately measured, but, in practice, bias and unknown confounders usually remain additional potential sources of error, often of unknown magnitude and clinical impact. Causality—the most clinically useful relation between exposure and outcome—can rarely be defnitively determined from observational studies because intentional, controlled manipu- lations of exposures are not involved. In this article, we review several types of observa- tional clinical research: case series, comparative case-control and cohort studies, and hybrid designs in which case-control analyses are performed on selected members of cohorts. We also discuss the analytic issues that arise when groups to be compared in an observational study, such as patients receiving different therapies, are not comparable in other respects. (Anesth Analg 2015;121:1043–51) bservational clinical studies are attractive because Group, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists they are relatively inexpensive and, perhaps more Anesthesia Quality Institute. importantly, can be performed quickly if the required Recent retrospective perioperative studies include data O 1,2 data are already available. -

The Value of Case Reports in Systematic Reviews from Rare Diseases

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article The Value of Case Reports in Systematic Reviews from Rare Diseases. The Example of Enzyme Replacement Therapy (ERT) in Patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II (MPS-II) Miguel Sampayo-Cordero 1,2,*, Bernat Miguel-Huguet 3, Andrea Malfettone 1,2, José Manuel Pérez-García 1,2,4, Antonio Llombart-Cussac 1,2,5, Javier Cortés 1,2,4,6, Almudena Pardo 7 and Jordi Pérez-López 8 1 Medica Scientia Innovation Research (MedSIR), Ridgewood, NJ 07450, USA; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (J.M.P.-G.); [email protected] (A.L.-C.); [email protected] (J.C.) 2 Medica Scientia Innovation Research (MedSIR), 08018 Barcelona, Spain 3 Department of Surgery, Hospital de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, 08907 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 4 Institute of Breast Cancer, Quiron Group, 08023 Barcelona, Spain 5 Hospital Arnau de Vilanova, Universidad Católica de Valencia “San Vicente Mártir”, 46015 Valencia, Spain 6 Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 08035 Barcelona, Spain 7 Albiotech Consultores y Redacción Científica S.L., 28035 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 8 Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Vall d’Hebron, 08035 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 3 August 2020; Accepted: 7 September 2020; Published: 10 September 2020 Abstract: Background: Case reports are usually excluded from systematic reviews. Patients with rare diseases are more dependent on novel individualized strategies than patients with common diseases. We reviewed and summarized the novelties reported by case reports in mucopolysaccharidosis type II (MPS-II) patients treated with enzyme replacement therapy (ERT). -

Download, And

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/19002121; this version posted July 15, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Evaluation of Indicators of Reproducibility and Transparency in Published Cardiology Literature Short Title: Anderson et al.; Indicators of Reproducibility in Cardiology J. Michael Anderson, B.S.1, Bryan Wright, B.G.S.1, Daniel Tritz, B.S.1, Jarryd Horn, B.S.1, Ian Parker, D.O.2, Daniel Bergeron, D.O.2, Sharolyn Cook, D.O.2, Matt Vassar, PhD1 1. Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA 2. Oklahoma State University Medical Center - Department of Cardiology, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA Corresponding Author: Mr. J. Michael Anderson, Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences, 1111 W 17th St Tulsa, OK 74107, United States; Fax: 918-561-8428; Telephone: 918-521-8774; Email: [email protected] Word Count: 7041 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/19002121; this version posted July 15, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract: Background The extent of reproducibility in cardiology research remains unclear. Therefore, our main objective was to determine the quality of research published in cardiology journals using eight indicators of reproducibility. -

Study Types Transcript

Study Types in Epidemiology Transcript Study Types in Epidemiology Welcome to “Study Types in Epidemiology.” My name is John Kobayashi. I’m on the Clinical Faculty at the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, at the School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of Washington in Seattle. From 1982 to 2001, I was the state epidemiologist for Communicable Diseases at the Washington State Department of Health. Since 2001, I’ve also been the foreign adviser for the Field Epidemiology Training Program of Japan. About this Module The modules in the epidemiology series from the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice are intended for people working in the field of public health who are not epidemiologists, but who would like to increase their understanding of the epidemiologic approach to health and disease. This module focuses on descriptive and analytic epide- miology and their respective study designs. Before you go on with this module, we recommend that you become familiar with the following modules, which you can find on the Center’s Web site: What is Epidemiology in Public Health? and Data Interpretation for Public Health Professionals. We introduce a number of new terms in this module. If you want to review their definitions, the glossary in the attachments link at the top of the screen may be useful. Objectives By now, you should be familiar with the overall approach of epidemiology, the use of various kinds of rates to measure disease frequency, and the various ways in which epidemiologic data can be presented. This module offers an overview of descriptive and analytic epidemiology and the types of studies used to review and investigate disease occurrence and causes. -

Overview of Epidemiological Study Designs

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS PEER Liberia Project UMass Medical School Collaborations in Liberia 2018-11 Overview of Epidemiological Study Designs Richard Ssekitoleko Yale University Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/liberia_peer Part of the Clinical Epidemiology Commons, Epidemiology Commons, Family Medicine Commons, Infectious Disease Commons, Medical Education Commons, and the Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons Repository Citation Ssekitoleko R. (2018). Overview of Epidemiological Study Designs. PEER Liberia Project. https://doi.org/ 10.13028/fp3z-mv12. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/liberia_peer/5 This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in PEER Liberia Project by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Overview of Epidemiological study Designs Richard Ssekitoleko Department of Global Health Yale University 1.1 Objectives • Understand the different epidemiological study types • Get to know what is involved in each type of study • Understand the strengths and Limitations of each study type Key terms • Population • Consists of all elements and is the group from which a sample is drawn • A sample is a subset of a population • Parameters • Summary data from a population • Statistics • Summary data from a sample • Validity • Extent to which a conclusion or statistic is well-founded and likely corresponds accurately to the parameter. Hierarchy of Evidence Study type Observational Interventional Descriptive Experiment Ecological Randomized Controlled Trial Cross-sectional Case-control Cohort Overview of Epidemiologic Study Designs Validity *anecdotes Cost Understanding What Physicians Mean: In my experience … once. -

Letter to the Editor Concerning “Low Virulence Bacterial Infections in Cervical Intervertebral Discs: a Prospective Case Series” by Chen Y, Wang X, Zhang X, Et Al

European Spine Journal (2019) 28:1242–1245 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-018-5671-4 LETTER TO THE EDITOR Letter to the Editor concerning “Low virulence bacterial infections in cervical intervertebral discs: a prospective case series” by Chen Y, Wang X, Zhang X, et al. (Eur Spine J; 2018: doi:10.1007/ s00586‑018‑5582‑4) Manu N. Capoor1,4 · Andrew McDowell2 · Assaf Raz1 · Peter Lambert3 · Ondrej Slaby4 Received: 22 May 2018 / Accepted: 17 June 2018 / Published online: 23 June 2018 © The Author(s) 2018 Dear Editor, by homogenization with a mortar and pestle, with the option of a short sonication step. In contrast, there was We have read with great interest the manuscript by Chen no evidence of CoNS present in disc tissue as a bioflm. et al., which provides an interesting and potentially impor- The process of disrupting P. acnes bioflm is a recog- tant perspective into low virulence infections in cervical nized approach to maximize the detection of P. acnes intervertebral discs [1]. Given our experience in relation to and CoNS organisms associated with other infections, the study of infection amongst patients undergoing lumbar notably those associated with prosthetic joints [3]. microdiscectomy surgery [2], we would like to highlight 2. The study population is underpowered based on a sample what we consider to be some methodological and data analy- size calculation: Two meta-analyses of previous studies sis limitations within the study that could impact on the fnal addressing infection of intervertebral discs reported a results and conclusion. These are: pooled prevalence of bacteria at 34 and 36.2%, respec- tively, with P. -

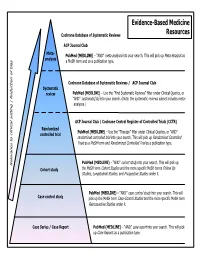

Common Types of Questions: Types of Study Designs

Evidence-Based Medicine Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Resources ACP Journal Club Meta- is as PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” meta-analysis into your search. This will pick up Meta-Analys analysis s a MeSH term and as a publication type. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews / ACP Journal Club Systematic review PubMed (MEDLINE) – Use the ”Find Systematic Reviews” filter under Clinical Queries, or “AND” systematic[sb] into your search. (Note: the systematic reviews subset includes meta- analyses.) tting | Reduction of bia ACP Journal Club / Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCTR) Randomized PubMed (MEDLINE) – Use the “Therapy” filter under Clinical Queries, or “AND” controlled trial randomized controlled trial into your search. This will pick up Randomized Controlled Trials as a MeSH term and Randomized Controlled Trial as a publication type. PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” cohort study into your search. This will pick up Relevance to clinical se Cohort study the MeSH term Cohort Studies and the more specific MeSH terms Follow Up Studies, Longitudinal Studies, and Prospective Studies under it. PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” case control study into your search. This will Case control study pick up the MeSH term Case-Control Studies and the more specific MeSH term Retrospective Studies under it. Case Series / Case Report PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” case report into your search. This will pick up Case Reports as a publication type. COMMON TYPES OF QUESTIONS: TYPES OF STUDY DESIGNS: Therapy -- how to select treatments to offer patients that do more good A Meta-analysis takes a systematic review one step further by than harm and that are worth the efforts and costs of using them combining all the results using accepted statistical methodology. -

Choosing the Right Study Design Conflicts of Interest

Choosing the right study design Conflicts of interest I have received funding for the membership of Data Safety and Monitoring Boards, Advisory Boards and for the preparation of educational materials from: • Gilead Sciences • ViiV Healthcare • Janssen‐Cilag Main types of study design BEST QUALITY Randomised controlled trial (RCT) EVIDENCE Cohort study Case‐control study Cross‐sectional study Case series/case note review ‘Expert’ opinion WORST QUALITY EVIDENCE Experimental vs. Observational Experimental study Investigator intervenes in the care of the patient in a pre‐planned, experimental way and records the outcome Observational study Investigator does not intervene in the care of a patient in any way, other than what is routine clinical care; investigator simply records what happens Cross‐sectional vs. Longitudinal Cross‐sectional study Patients are studied at a single time‐point only (e.g. patients are surveyed on a single day, patients are interviewed at the start of therapy) Longitudinal study Patients are followed over a period of time (days, months, years…) Assessing causality (Bradford Hill criteria) Cause should precede effect Association should be plausible (i.e. biologically sensible) Results from different studies should be consistent Association should be strong Should be a dose‐response relationship between the cause and effect Removal of cause should reduce risk of the effect Incidence vs. prevalence Incidence: proportion of patients without the event of interest who develop the event over the study period ‐ Can only estimate from a longitudinal study ‐ Must exclude those who have the event at start of study from the calculation Prevalence: proportion of all patients in study who have the event at a particular point in time ‐ Can estimate prevalence from longitudinal or cross‐sectional studies ‐ Generally include all patients in calculation Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) Experimental and longitudinal Comparative –comparison of two or more treatment strategies (e.g. -

Levels of Evidence

Levels of Evidence PLEASE NOTE: Evidence levels are only used for research involving human subjects. Basic science and animal studies should be listed as NA. Level Therapy/Prevention or Etiology/Harm Prognosis Study Study 1a Systematic review of randomized Systematic review of prospective cohort controlled trials studies 1b Individual randomized controlled trial Individual prospective cohort study 2a Systematic review of cohort studies Systematic review of retrospective cohort studies 2b Individual cohort study Individual retrospective cohort study 2c “Outcomes research” “Outcomes research” 3a Systematic review of case-control studies 3b Individual case-control study 4 Case series (with or without comparison) Case series (with or without comparison) 5 Expert opinion Expert opinion NA Animal studies and basic research Animal studies and basic research Case-Control Study. Case-control studies, which are always retrospective, compare those who have had an outcome or event (cases) with those who have not (controls). Cases and controls are then evaluated for exposure to various risk factors. Cases and controls generally are matched according to specific characteristics (eg, age, sex, or duration of disease). Case Series. A case series describes characteristics of a group of patients with a particular disease or patients who had undergone a particular procedure. A case series may also involve observation of larger units such as groups of hospitals or municipalities, as well as smaller units such as laboratory samples. Case series may be used to formulate a case definition of a disease or describe the experience of an individual or institution in treating a disease or performing a type of procedure. A case series is not used to test a hypothesis because there is no comparison group.