The Impact of New Highways Upon Wilderness Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gwich'in Land Use Plan

NÀNHÀNH’ GEENJIT GWITRWITR’IT T’T’IGWAAIGWAA’IN WORKING FOR THE LAND Gwich’in Land Use Plan Gwich’in Land Use Planning Board August 2003 NÀNH’ GEENJIT GWITR’IT T’IGWAA’IN / GWICH’IN LAND USE PLAN i ii NÀNH’ GEENJIT GWITR’IT T’IGWAA’IN / GWICH’IN LAND USE PLAN Ta b le of Contents Acknowledgements . .2 1Introduction . .5 2Information about the Gwich’in Settlement Area and its Resources . .13 3 Land Ownership, Regulation and Management . .29 4 Land Use Plan for the Future: Vision and Land Zoning . .35 5 Land Use Plan for the Future: Issues and Actions . .118 6Procedures for Implementing the Land Use Plan . .148 7Implementation Plan Outline . .154 8Appendix A . .162 NÀNH’ GEENJIT GWITR’IT T’IGWAA’IN / GWICH’IN LAND USE PLAN 1 Acknowledgements The Gwich’in are as much a part of the land as the land is a part of their culture, values, and traditions. In the past they were stewards of the land on which they lived, knowing that their health as people and a society was intricately tied to the health of the land. In response to the Berger enquiry of the mid 1970’s, the gov- ernment of Canada made a commitment to recognize this relationship by estab- lishing new programmes and institutions to give the Gwich’in people a role as stewards once again. One of the actions taken has been the creation of a formal land use planning process. Many people from all communities in the Gwich’in Settlement Area have worked diligently on land use planning in this formal process with the government since the 1980s. -

Yukon & the Dempster Highway Road Trip

YUKON & THE DEMPSTER HIGHWAY ROAD TRIP Yukon & the Dempster Highway Road Trip Yukon & Alaska Road Trip 15 Days / 14 Nights Whitehorse to Whitehorse Priced at USD $1,642 per person INTRODUCTION The Dempster Highway road trip is one of the most spectacular self drives on earth, and yet, many people have never heard of it. It’s the only road in Canada that takes you across the Arctic Circle, entering the land of the midnight sun where the sky stays bright for 24 hours a day. Explore subarctic wilderness at Tombstone National Park, witness wildlife at the Yukon Wildlife Preserve, see the world's largest non-polar icefields and discover the "Dog Mushing Capital of Alaska." In Inuvik, we recommend the sightseeing flight to see the Arctic Ocean from above. Itinerary at a Glance DAY 1 Whitehorse | Arrival DAY 2 Whitehorse | Yukon Wildlife Preserve DAY 3 Whitehorse to Hains Junction | 154 km/96 mi DAY 4 Kluane National Park | 250 km/155 mi DAY 5 Haines Junction to Tok | 467 km/290 mi DAY 6 Tok to Dawson City | 297 km/185 mi DAYS 7 Dawson City | Exploring DAY 8 Dawson City to Eagle Plains | 408 km/254 mi DAY 9 Eagle Plains to Inuvik | 366 km/227 mi DAY 10 Inuvik | Exploring DAY 11 Inuvik to Eagle Plains | 366 km/227 mi DAY 12 Eagle Plains to Dawson City | 408 km/254 mi Start planning your vacation in Canada by contacting our Canada specialists Call 1 800 217 0973 Monday - Friday 8am - 5pm Saturday 8.30am - 4pm Sunday 9am - 5:30pm (Pacific Standard Time) Email [email protected] Web canadabydesign.com Suite 1200, 675 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC, V6B 1N2, Canada 2021/06/14 Page 1 of 5 YUKON & THE DEMPSTER HIGHWAY ROAD TRIP DAY 13 Dawson City to Mayo | 230 km/143 mi DAY 14 Mayo to Whitehorse | 406 km/252 mi DAY 15 Whitehorse | Departure MAP DETAILED ITINERARY Day 1 Whitehorse | Arrival Welcome to the “Land of the Midnight Sun”. -

Permafrost Terrain Dynamics and Infrastructure Impacts Revealed by UAV Photogrammetry and Thermal Imaging

remote sensing Article Permafrost Terrain Dynamics and Infrastructure Impacts Revealed by UAV Photogrammetry and Thermal Imaging Jurjen van der Sluijs 1 , Steven V. Kokelj 2,*, Robert H. Fraser 3 , Jon Tunnicliffe 4 and Denis Lacelle 5 1 NWT Centre for Geomatics, Government of Northwest Territories, Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9, Canada; [email protected] 2 Northwest Territories Geological Survey, Government of Northwest Territories, Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9, Canada 3 Canada Centre for Mapping and Earth Observation, Natural Resources Canada, Ottawa, ON K1A 0E4, Canada; [email protected] 4 School of Environment, University of Auckland, Auckland 1142, New Zealand; [email protected] 5 Department of Geography, Environment and Geomatics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON K1N 6N5, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-867-767-9211 (ext. 63214) Received: 9 July 2018; Accepted: 12 October 2018; Published: 3 November 2018 Abstract: Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) systems, sensors, and photogrammetric processing techniques have enabled timely and highly detailed three-dimensional surface reconstructions at a scale that bridges the gap between conventional remote-sensing and field-scale observations. In this work 29 rotary and fixed-wing UAV surveys were conducted during multiple field campaigns, totaling 47 flights and over 14.3 km2, to document permafrost thaw subsidence impacts on or close to road infrastructure in the Northwest Territories, Canada. This paper provides four case studies: (1) terrain models and orthomosaic time series revealed the morphology and daily to annual dynamics of thaw-driven mass wasting phenomenon (retrogressive thaw slumps; RTS). Scar zone cut volume estimates ranged between 3.2 × 103 and 5.9 × 106 m3. -

7 Day Yukon and NWT - Self Drive to the Arctic Sea

Tour Code 7YNWT 7 Day Yukon and NWT - Self Drive to the Arctic Sea 7 days Created on: 27 Sep, 2021 Day 1: Arrive in Whitehorse, Yukon Welcome to Whitehorse nestled on the banks of the famous Yukon River surrounded by mountains and pristine lakes. Whitehorse makes the perfect base for exploring Canada's Great North. It is a city that blends First Nations culture, gold rush history, interesting museums and an energetic, creative vibe all with a stunning wilderness backdrop. Overnight: Whitehorse Day 2: Whitehorse, Yukon The capital of the Yukon, Whitehorse, offers a charming inside to the history of the North. We visit the Visitor Centre to learn about the different regions of the Yukon, the SS Klondike, a paddle wheeler ship and the Old Log Church, both restored relicts used in the Goldrush and not to forget the world's longest wooden fish ladder and a Log Skyscraper. To finish with an inspiration from the North we will have a guided tour through the MacBride Museum. The afternoon is set aside to explore the capital of the Yukon on foot. We suggest a trip to the Visitor Centre to learn about the different regions of the Yukon and pick up some maps. We suggest a walk to the riverfront Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre. This award-winning building celebrates the heritage, culture and contemporary way of life of Yukon's Kwanlin Dün First Nations people. Whitehorse has great shops, galleries and museums that are open all year. Take a stroll down Main Street or spend time with the locals in the lively cafés. -

Dempster Highway... Dempster Highway

CANADA’S For further Our natural The Taiga Plains – DempsterDempster taiga, a Russian word, information... regions refers to the northern Please contact: One of the most edge of the great boreal Tourism and Parks – appealing aspects of the forest and describes Highway...Highway... Industry, Tourism and Investment, trip up the Dempster is much of the Mackenzie Government of the Northwest Territories, the contrast between the Weber Wolfgang River watershed, Northwest Territories Bag Service #1 DEM, Inuvik NT X0E 0T0 Canada natural regions encountered. Canada’s largest. The e-mail: [email protected] Mountains, valleys, plateaus river valley acts as Phone: (867) 777-7196 Fax: (867) 777-7321 and plains and the arctic a migratory corridor for the hundreds of thousands of Northwest Territories Campground Reservations – tundra are all to be waterfowl that breed along the arctic coast in summer. www.campingnwt.ca discovered along the way. Typical animals found include moose, wolf, black bear, Community Information – We have identified the marten and lynx. The barren ground caribou that migrate www.inuvikinfo.com five principal natural regions onto the tundra to the north in the summer months, retreat www.inuvik.ca or “ecozones” by colour on to the taiga forest to over-winter. NWT Arctic Tourism – the map for you: The Southern Arctic – Phone Toll Free: 1-800-661-0788 The Boreal Cordillera – labelled as the ’Barren www.spectacularnwt.com mountain ranges with Lands’ by early European National Parks – numerous high peaks visitors, because of the Canadian Heritage, Parks Canada, and extensive plateaus, lack of trees. Trees do Western Arctic District Office, separated by wide valleys in fact grow here, but Box 1840, Inuvik NT X0E 0T0 and lowlands. -

Northern Connections

NORTHERN CONNECTIONS A Multi-Modal Transportation Blueprint for the North FEBRUARY 2008 Government of Yukon Photos and maps courtesy of: ALCAN RaiLink Inc. Government of British Columbia Government of Northwest Territories Government of Nunavut Government of Yukon Designed and printed in Canada’s North Copyright February 2008 ISBN: 1-55362-342-8 MESSAGE FROM MINISTERS It is our pleasure to present Northern Connections: A Multi-Modal Transportation Blueprint for the North, a pan-territorial perspective on the transportation needs of Northern Canada. This paper discusses a vision for the development of northern transportation infrastructure in the context of a current massive infrastructure decit. Research has proven that modern transportation infrastructure brings immense benets. The northern transportation system of the future must support economic development, connect northern communities to each other and to the south, and provide for enhanced sovereignty and security in Canada’s north. This document complements a comprehensive national transportation strategy – Looking to the Future: A Plan for Investing in Canada’s Transportation System – released under the auspices of the Council of the Federation in December 2005. The three territories support the details contained in Looking to the Future that call for a secure, long-term funding framework for transportation infrastructure that will benet all Canadians. Equally important, northern territories stress that this national strategy – and any subsequent funding mechanisms that follow – must account for unique northern needs and priorities, which would be largely overlooked using nation-wide criteria only. This paper is also consistent with A Northern Vision: A Stronger North and a Better Canada, the May 2007 release of a pan-territorial vision for the north. -

Yukon Wildlife Viewing Guide Safe Wildlife Viewing

Capital letters and common names: the common names of animals begin with capital letters to allow the reader to distinguish between species. For example, a Black Bear is a species of bear, not necessarily a bear that is black. All photos © Yukon government unless otherwise credited. ©Government of Yukon 2019 (13th edition); first printed 1995 ISBN 978-1-55362-814-9 For more information on viewing Yukon wildlife, contact: Government of Yukon Wildlife Viewing Program Box 2703 (V-5R) Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6 Phone: 867-667-8291 Toll free in Yukon: 1-800-661-0408, ext. 8291 [email protected] Yukon.ca Find us on Facebook at “Yukon Wildlife Viewing” Cover photo: Wilson’s Warbler, Ben Schonewille; Moose, YG; Least Weasel, Gord Court. Aussi disponible en français comme <<Guide d’observation de la faune et de la flore du Yukon>> Diese Broschüre ist als auch auf Deutsch erhältlich When we say “Yukon wildlife,” many Table of contents people envision vast herds of caribou, a majestic Moose, or a Grizzly Bear fishing How to use this guide 4 in a pristine mountain stream. However, Safe wildlife viewing 5 there is far more to wildlife than large, showy mammals. Wildlife viewing tips 6 Take a moment to quietly observe a Alaska Highway 8 pond, rest on a sunny slope, or relax Highway #1 under a canopy of leaves, and you might catch a glimpse of the creatures big and South Klondike Highway 26 small that call Yukon home. The key to Highway #2 successful wildlife viewing is knowing North Klondike Highway 28 where and how to look. -

Dempster Road Map Page 1.Ai

N INFORMATIO ANALYSIS RESEARCH 1 folded map. folded 1 Geological Survey, NWT Open Report 2007-009 & YGS Open File 2007-11, File Open YGS & 2007-009 Report Open NWT Survey, Geological ESINEOFFICE GEOSCIENCE most northwestern road; Northwest Territories Geoscience Office and Yukon and Office Geoscience Territories Northwest road; northwestern most Highway, Northwest Territories & Yukon, A geological roadmap for Canada’s for roadmap geological A Yukon, & Territories Northwest Highway, OTWS TERRITORIES NORTHWEST Jones, A.L. & Pyle, L.J. (compilers), 2007. Roadside Geology of the Dempster the of Geology Roadside 2007. (compilers), L.J. Pyle, & A.L. Jones, Citation locally if certain sites are critical to your visit. Enjoy the geology and the drive! the and geology the Enjoy visit. your to critical are sites certain if locally a result some distances recorded on this map will be inexact. Please check Please inexact. be will map this on recorded distances some result a the old route at Chapman Lake (Km 116). (Km Lake Chapman at route old the the kilometre posts (northern section) are periodically moved or re-placed. As re-placed. or moved periodically are section) (northern posts kilometre the www.explorenwt.com www.travelyukon.com www.explorenwt.com McPherson. The patrols were discontinued in 1921 and the highway intersects highway the and 1921 in discontinued were patrols The McPherson. quarries are opened and closed by highway maintenance crews. Furthermore, crews. maintenance highway by closed and opened are quarries planning your trip, please consult the following websites and links therein: links and websites following the consult please trip, your planning annual mid-winter dogsled excursions of the Dawson RNWMP to Fort to RNWMP Dawson the of excursions dogsled mid-winter annual parts of the road are re-constructed, and various borrow (gravel) pits and pits (gravel) borrow various and re-constructed, are road the of parts halfway) at Km 369, to Inuvik at Km 717. -

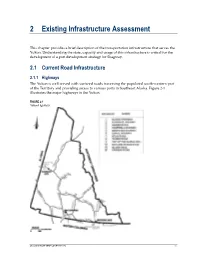

2 Existing Infrastructure Assessment

2 Existing Infrastructure Assessment This chapter provides a brief description of the transportation infrastructure that serves the Yukon. Understanding the state, capacity and usage of this infrastructure is critical for the development of a port development strategy for Skagway. 2.1 Current Road Infrastructure 2.1.1 Highways The Yukon is well served with surfaced roads traversing the populated south-western part of the Territory and providing access to various ports in Southeast Alaska. Figure 2-1 illustrates the major highways in the Yukon. FIGURE 2-1 Yukon Highways SKAGWAY PORT DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2-1 2. EXISTING INFRASTRUCTURE ASSESSMENT The main highway across the Yukon is the Alaska Highway. It originates in Dawson Creek, BC and runs for 909 kilometres (km) through the Yukon from the BC border east of Watson Lake to the Interior Alaska border at Beaver Creek. The Alaska Highway and the Haines Road were built in 1943 as military pioneer roads. They were improved during the 1950s and substantially upgraded in the 1980s. These two principal highways are well-paved and well-maintained. Other Yukon highways include the Klondike Highway from Skagway through Whitehorse to Dawson City and the Dempster Highway from east of Dawson City to Inuvik. The South Klondike Highway parallels the old White Pass trail between Skagway and Log Cabin. Whitehorse is the centre of travel in the Yukon. Table 2-1 summarizes distances to the nearest ports and centers from Whitehorse, indicating the remote nature of the Yukon. TABLE 2-1 Distances from Whitehorse -

Wildlife Viewing Guide

WILDLIFE VIEWING YUKON WILDLIFE VIEWING GUIDE ALONG MAJOR HIGHWAYS Knowing where and how to look Beaufort Sea (Arctic Ocean) Tintina Trench D Shakwak Trench YUKON A NATIONAL PARKS A Ivvavik National Park C Kluane National Park & Reserve WILDLIFE VIEWING GUIDE B B Vuntut National Park M a c T k TERRITORIAL PARKS e n Old Crow z D Herschel Island - Qikiqtaruk H Asi Keyi i e E Tombstone I Coal River Springs Porcupine R V R iv i e v F Agay Mene J Ni’iinlii Njik (Fishing Branch) ALONG MAJOR HIGHWAYS r e r G Kusawa HABITAT PROTECTION AREAS J K Ddhaw Ghro P Tagish Narrows L Tsâwnjik Chu (Nordenskiold) Q Devil’s Elbow r M Łútsäw Wetland R Pickhandle Lakes e v N Horseshoe Slough S Ta’Tla Mun Ri 5 Peel O Lewes Marsh T Old Crow Flats NATIONAL WILDLIFE AREAS U Nisutlin Delta YUKON HIGHWAYS E Alaska 1 Alaska Highway 9 2 South & North Klondike Highways Dawson Keno 3 Haines Road 4 Robert Campbell Highway Mayo N 5 Dempster Highway 11 o Q r 6 South & North Canol Roads N t Stewart Crossing h r K Atlin Road e w 7 v i Y u e Tagish Road R k Pelly Crossing s 8 on t Riv M P Beaver Creek er e T 9 Top of the World Highway lly 6 e 2 R r S i Nahanni Range Road e v r 10 t e i i r t h Faro o R 4 r 11 Silver Trail W Carmacks i es Kluane Lake L Ross River 1 H Burwash Landing T 4 e s Destruction Bay l 6 in 10 L R ia rd C R i 1 ve Haines Junction WHITEHORSE r O 2 P G Teslin Watson Lake I 3 Carcross 8 F 7 U 1 Tatshenshini River B.C. -

DISCOVER the YUKON - SELF DRIVE (11834) Grizzly Bear Near Alaska Highway Near Haines Junction Credit: Sheena Greenlaw

VIEW PACKAGE PEACE OF MIND BOOKING PLAN DISCOVER THE YUKON - SELF DRIVE (11834) Grizzly bear near Alaska Highway near Haines Junction Credit: Sheena Greenlaw Discover the Yukon on this 15 day Self Drive adventure. There's over 350,000 square kilometres of mountain vistas, boreal forests, wild rivers and crystal blue lakes. Yukon's natural splendour is Duration truly jaw-dropping. 14 nights Canada Destinations SELF-DRIVE WILDLIFE Canada INDEPENDENT HOLIDAY PACKAGES Travel Departs Whitehorse Highlights Travel Ends See the grizzly bears in Kluane National Park Cross the Artic Circle on the iconic Whitehorse and the Dall sheep grazing on Sheep Dempster Highway Mountain. Experiences Explore the historical sights of Dawson City Visit the Yukon Wildlife Preserve Self-Drive, Wildlife at your leisure Travel Style Independent Holiday Packages Your discovery of the Yukon starts in Whitehorse. Explore the Main Street ambience, shopping, restaurants and nature on its doorstep. The Yukon has 10 times more moose, bears, wolves, caribou, goats and sheep than people. Enjoy the unique wildlife experience on your visit to Yukon Wildlife Preserve. A two hour drive along the historical Alaska Highway takes you to Haines Junction, a picture- postcard village and the gateway to exploring the the pristine Kluane National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It's a dramatic landscape of broad, lush valleys and monumental mountain ranges, where wildlife is plentiful. On your way to Tok look out for the Dall sheep gracing alongside the mountain slopes. Continue onto Dawson City, where the lure of gold drew thousands of men, and some women to this region. -

Dempster Highway Grand Tour from Whitehorse to the Arctic Ocean! June 16-21, 2019 August 25-30, 2019

Dempster Highway Grand Tour from Whitehorse to the Arctic Ocean! June 16-21, 2019 August 25-30, 2019 Fly one way/Drive one way 6-day Yukon/NWT Package Tour $3,290 per person plus GST. This package offers you the opportunity to see the remote and wild countryside from Whitehorse all the way north to the Arctic Ocean. You will travel on the North Klondike Highway or fly to Dawson City. In Dawson City you get a tour of this charming unique town. Itinerary Sunday You will fly from Whitehorse to Dawson City and Olav will meet you there for a tour of Dawson City in the afternoon. You will also have a chance to do some gold panning. You will have to pay an extra $135 pp to fly to Dawson City instead of driving with Olav who will already be in Whitehorse that Sunday dropping another group off. Monday Olav will pick you up at your hotel at 9 am. Today you will start your drive up the Dempster Highway where you will see the Tombstone and Ogilvie Mountains and continue on to Eagle Plains, the half-way point on the Dempster Highway. You will spend the night there. There will be time to stop and take pictures at inspiring view points periodically during the drive. Tuesday Today you will travel on to the Arctic Circle Crossing where you will have the chance to walk around and take some pictures at the sign with a spectacular backdrop of the mountains. We will spend most of our time in the beautiful Richardson Mountains looking for wildlife and taking in the spectacular scenery of this wild and remote wilderness.