T He Language of Faith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

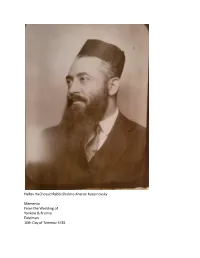

Shlomo Aharon Kazarnovsky 1

HaRav HaChossid Rabbi Sholmo Aharon Kazarnovsky Memento From the Wedding of Yankele & Frumie Eidelman 10th Day of Tammuz 5781 ב״ה We thankfully acknowledge* the kindness that Hashem has granted us. Due to His great kindness, we merited the merit of the marriage of our children, the groom Yankele and his bride, Frumie. Our thanks and our blessings are extended to the members of our family, our friends, and our associates who came from near and far to join our celebration and bless our children with the blessing of Mazal Tov, that they should be granted lives of good fortune in both material and spiritual matters. As a heartfelt expression of our gratitude to all those participating in our celebration — based on the practice of the Rebbe Rayatz at the wedding of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin of giving out a teshurah — we would like to offer our special gift: a compilation about the great-grandfather of the bride, HaRav .Karzarnovsky ע״ה HaChossid Reb Shlomo Aharon May Hashem who is Good bless you and all the members of Anash, together with all our brethren, the Jewish people, with abundant blessings in both material and spiritual matters, including the greatest blessing, that we proceed from this celebration, “crowned with eternal joy,” to the ultimate celebration, the revelation of Moshiach. May we continue to share in each other’s simchas, and may we go from this simcha to the Ultimate Simcha, the revelation of Moshiach Tzidkeinu, at which time we will once again have the zechus to hear “Torah Chadashah” from the Rebbe. -

TORAH Weeklyparshat Beshalach 13 - 19 January, 2019 the Torah Finds It Necessary to Too Would Make Their Own 7 - 13 Shevat, 5779 the BONES of Mention Explicitly

בס״ד TORAH WEEKLYParshat Beshalach 13 - 19 January, 2019 the Torah finds it necessary to too would make their own 7 - 13 Shevat, 5779 THE BONES OF mention explicitly. Why? transition successfully. JOSEPH The answer is that Ever since leaving Torah : They say adapt or die. Joseph was unique. While Egypt, we’ve been wandering. Exodus 13:17 - 17:16 But must we jettison the old his brothers were simple And every move has brou- to embrace the new? Is the shepherds tending to their ght with it its own challen- Haftorah: choice limited to modern or flocks, Joseph was running ges. Whether from Poland the affairs of state of the mi- to America or Lithuania to Judges 4:4 - 5:31 antiquated, or can one be a contemporary traditionalist? ghtiest superpower of the day. South Africa, every transition Do the past and present ever To be a practicing Jew while has come with culture shocks CALENDARS co-exist? blissfully strolling through to our spiritual psyche. How We have Jewish At the beginning the meadows is not that com- do you make a living and still plicated. Alone in the fields, keep the Shabbat you kept in Calendars, if you would of this week’s Parshah we communing with nature, and the shtetl when the factory like one, please send us read that Moses himself was occupied with a special away from the hustle and bu- boss says “Cohen, if you don’t a letter and we will send mission as the Jews were stle of city life, one can more come in on Saturday, don’t you one, or ask the Rab- leaving Egypt. -

Unfazed Program Companion

PROGRAM COMPANION Art: Sefira Ross THIS PUBLICATION CONTAINS SACRED CONTENT. PLEASE TREAT IT WITH RESPECT. 2 YOU CAN OVERCOME! A Letter From The Rebbe By the Grace of G‑d of the person." 21 Cheshvan, 5737 Unlike a human who, when delegating a job to Greetings and Blessings! someone or something, can err in his calculation, I have received your letter, and I will mention it is not possible for G‑d to err, G‑d forbid, and to you in a Prayer that G‑d, blessed be He, Who demand the impossible. watches over everyone and Who sustains and It is only that something can be easy for one provides for the entire world with his Goodness person to achieve, while the other person has to and Kindness, will find your livelihood and will overcome difficulties and challenges in order to improve your situation with everything that you achieve that same thing, but it's clear that everyone and your family need. receives the strength to fulfil G‑d's Mitzvot in their It is certainly unnecessary to explain at length totality. that daily behavior according to G‑d's will is the Even more so, when one person is given extra way to receive G‑d's blessing, and it is understood difficulties and challenges, it is a sign that he was that it is not proper to give conditions to G‑d. given more strength, and with patience and a firm However, it is important to emphasize that every resolve to withstand the challenges, and with faith single Jew was given the strength to live according in G‑d, blessed be He, he will see that the obstacles to G‑d's will. -

18 Korach Email Draft

ה“ב ע ר ש “ ק פ ר ש ת ק ר ח “כ, ב ס י ו ן , ת ש ע א“ VOLUME 1, ISSUE 18 INSIDE THIS A Visit to the Ohel - Rostov 5685 I S S U E : As Gimmel Tammuz approaches, we found it Leben Miten Rebben 1 The Rebbe handed me a packet of Panim and appropriate to quote the following section from the memoirs instructed that I only place them on the Ohel of Horav Yisroel Jacobson . It was in the year 5685 without reading them at all beforehand. Whereas Serpa Pinto 2 (1925), shortly after the rise of the Communist regime in his own personal Pan , I was to read only once and Russia when the Frierdiker Rebbe appointed him as his only upon reaching the Ohel, no earlier. I was personal Shliach to visit the Ohel of the Rebbe Rashab in Niggun — 3 absolutely forbidden to show it to anyone else or Alter Rebbe’s Niggunim Rostov on his Yahrtzei, Beis Nissan. From the words of the Frierdiker Rebbe in that Yechidus, we learn much about the to copy it down; no exceptions! (When I did read Biography - 3 significance of a Chossid visiting the Rebbe's Ohel, in it's it, I noticed that in the first section he requested Reb Berke Chein – 5 being not merely a stop at Kivrei Tzadikim (Chas Brochos for himself personally as a Rebbe, and Q&A - 4 V'Sholom), but an actual Yechidus with the Rebbe. (In the later as a leader of world Jewry, he mentioned and Learning Gemara following excerpt, "the Rebbe" refers to the Frierdiker articulated many of the problems encountering the Rebbe). -

Pessi and Dovie Levy ט‘ אלול ה‘תשפ“א the 17Th of August, 2021 © 2021

לזכות החתן הרה"ת שלום דובער Memento from the Wedding of והכלה מרת פעסיל ליווי Pessi and Dovie ולזכות הוריהם Levy מנחם מענדל וחנה ליווי ט‘ אלול ה‘תשפ“א הרב שלמה זלמן הלוי וחנה זיסלא The 17th of August, 2021 פישער שיחיו לאורך ימים ושנים טובות Bronstein cover 02.indd 1 8/3/2021 11:27:29 AM בס”ד Memento from the Wedding of שלום דובער ופעסיל שיחיו ליווי Pessi and Dovie Levy ט‘ אלול ה‘תשפ“א The 17th of August, 2021 © 2021 All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof, in any form, without prior permission, in writing. Many of the photos in this book are courtesy and the copyright of Lubavitch Archives. www.LubavitchArchives.com [email protected] Design by Hasidic Archives Studios www.HasidicArchives.com [email protected] Printed in the United States Contents Greetings 4 Soldiering On 8 Clever Kindness 70 From Paris to New York 82 Global Guidance 88 Family Answers 101 Greetings ,שיחיו Dear Family and Friends As per tradition at all momentous events, we begin by thanking G-d for granting us life, sustain- ing us, and enabling us to be here together. We are thrilled that you are able to share in our simcha, the marriage of Dovie and Pessi. Indeed, Jewish law high- lights the role of the community in bringing joy to the chosson and kallah. In honor of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin’s wedding in 1928, the Frierdiker Rebbe distributed a special teshurah, a memento, to all the celebrants: a facsimile of a letter written by the Alter Rebbe. -

RABBI COHEN - Mishmor Joins International Chidon

בס“ד FORMER CHIEF RABBI VISIT On his recent visit to Melbourne, Rabbi Shlomo Amar (former Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Israel) The Rabbinical College of Australia & NZ Newsletter visited the Rabbinical College. Arriving just before the conclusion of Friday’s study session, he addressed the student body. The Shluchim presented Rabbi Amar with a collection of Chidushei Torah thoughts published Forty years at the helm by Yeshivah-Gedolah over the course of the current Kinusim at YG year. Lag B’Omer with YG RABBI COHEN - Mishmor joins International Chidon 5774—2014 GROUP PHOTO YG Shabbaton FORTY YEARS AT THE HELM Former Chief Rabbi Visit 4 Menachem‐Av this year marks 40 years since Rabbi students. They come not only from Melbourne and Binyomin Cohen arrived in Melbourne to serve as Sydney, but from all around the world. Annual Photo Rosh Yeshivah of the Rabbinical College of Australia Rabbi Cohen is known far and wide as a ‘no nonsense’ and New Zealand. Rosh Yeshivah by whose schedule one can set a clock. Born and raised in London, Rabbi Cohen entered “My adherence to me is a natural thing for me, and Gateshead Yeshivah rather than university aer gives me a sense of order and stability,” he says. Shluchim and students of Yeshiva compleng his secondary schooling. While at Gedolah recently produced a His adherence to order has made its mark in the unique Ha- Gateshead, he studied some of the Lubavitcher gadah Shel Rebbe’s early Sichos (talks) and became aracted to internaonal Yeshivah world. According to the college’s Pesach enti- Lubavitch. -

Faith Within Reason, and Without Adam Friedmann the Parshah Introduces Us to the He Began to Stray in His Thinking (From Was Never Destined to Have Children

בס“ד Parshat Lech Lecha 11 Cheshvan, 5777/November 12, 2016 Vol. 8 Num. 10 This issue is sponsored by Jeffrey and Rochel Silver in memory of their dear friend, Moe Litwack z”l Faith Within Reason, and Without Adam Friedmann The parshah introduces us to the he began to stray in his thinking (from was never destined to have children. spiritual greatness of Avraham Avinu the idolatry of his surroundings) while However, Ramban (ibid. 15:2) notes that and recounts many of the trials that he was still small and began thinking part of Avraham’s concern stemmed he faced, as well as several day and night… And his heart strayed from his advanced age. Perhaps he interactions that he had with G-d. and understood until he comprehended didn’t merit the miracle required to have Only in the penultimate encounter, the path of truth and understood the a child at that stage. And yet, G-d which describes the brit bein habetarim route of justice using his correct promises that a direct child of Avraham (covenant between the parts) does intellect. And he knew that there is only will inherit him. It is in this moment Avraham speak. Responding to a one G-d and He conducts the spheres that the rational nature of Avraham’s promise from G-d, “I am your and He created everything, and there faith is challenged. In order to maintain protector, your reward is very isn’t any G-d in existence except Him.” his belief in G-d’s promise, Avraham great” (Bereishit 15:1), Avraham It was based on this awareness and the would need to abandon, at least in this expresses concern about his lack of conviction in the truth of his detail, his rational assumptions and progeny: “My Lord G-d, what can you philosophical analyses that Avraham move forward purely on the basis of his give me? I go childless…” (ibid. -

לתקן עולם במלכות ש-ד-י a Light Unto The

לתקן עולם במלכות ש-ד-י A Light unto the NationsOUR DUTY OF TEACHING SHEVA MITZVOS B’NEI NOACH Celebration 40 In the Presence YUD SHEVAT 5750 of Royalty PERSONAL ENCOUNTERS WITH THE REBBETZIN $4.99 SHEVAT 5777 ISSUE 53 (130) DerherContents SHEVAT 5777 ISSUE 53 (130) Shabbos at the Tavern 04 DVAR MALCHUS Celebration 40 06 YUD SHEVAT 5750 The Rebbe’s Life 15 KSAV YAD KODESH A Light unto the Nations 16 SHEVA MITZVOS B’NEI NOACH Junk Mail 30 THE WORLD REVISITED Days of Meaning 34 SHEVAT To the Last Detail About the Cover: DARKEI HACHASSIDUS Illuminating the world: In this month's magazine we feature the story 36 of the Rebbe's call to spread the moral education and observance of sheva Mitzvos b’nei Noach, for the benefit of all people. In the Presence of Royalty PERSONAL ENCOUNTERS 40 WITH THE REBBETZIN DerherEditorial “The nature of a nosi is, as determined by the meaning Seeing and recognizing hashgacha pratis has always been of the word itself, to uplift and elevate the people of his an integral part of darkei haChassidus, but the Rebbe made it generation. As the Torah says about Moshe Rabbeinu, who all the more real and teaches us how to live day-by-day with .lit. count heads this perspective in mind]—”נשא את ראש בני ישראל“ ,was commanded of the Jewish people] uplift the heads of the Jewish people… In this issue, we explore this subject in various sources Meaning, in addition to a nosi filling all the needs of the and see how it is illuminated in the Rebbe’s Torah (see people of his generation, feeling distressed when they’re in “Darkei HaChassidus” and “The World Revisited” columns). -

View Sample of This Item

Praise for Turning Judaism Outward “Wonderfully written as well as intensely thought provoking, Turning Judaism Outward is the most in-depth treatment of the life of the Rebbe ever written. !e author has managed to successfully reconstruct the history of one of the most important Jewish religious leaders of the 20th century, whose life has up to now been shrouded in mystery. A compassionate, engaging biography, this magni"cent work will open up many new avenues of research.” —Dana Evan Kaplan, author, Contemporary American Judaism: Transformation and Renewal; editor, !e Cambridge Companion to American Judaism “In contrast to other recent biographies of the Rebbe, Chaim Miller has availed himself of all the relevant textual sources and archival docu- ments to recount the details of one of the more fascinating religious leaders of the twentieth century. !rough the voice of the author, even the most seemingly trivial aspect of the Rebbe’s life is teeming with interest.... I am con"dent that readers of Miller’s book will derive great pleasure and receive much knowledge from this splendid and compel- ling portrait of the Rebbe.” —Elliot R. Wolfson, Abraham Lieberman Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, New York University “Only truly great biographers have been able to accomplish what Chaim Miller has with this book... I am awed by his work, and am now even more awed than ever before by the Rebbe’s personality and prodi- gious accomplishments.” —Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb, Executive Vice President Emeritus, Orthodox Union; Editor-in-Chief, Koren-Steinsaltz Talmud “A fascinating account of the life and legacy of a spiritual master. -

Exporting Zionism

Exporting Zionism: Architectural Modernism in Israeli-African Technical Cooperation, 1958-1973 Ayala Levin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Ayala Levin All rights reserved ABSTRACT Exporting Zionism: Architectural Modernism in Israeli-African Technical Cooperation, 1958-1973 Ayala Levin This dissertation explores Israeli architectural and construction aid in the 1960s – “the African decade” – when the majority of sub-Saharan African states gained independence from colonial rule. In the Cold War competition over development, Israel distinguished its aid by alleging a postcolonial status, similar geography, and a shared history of racial oppression to alleviate fears of neocolonial infiltration. I critically examine how Israel presented itself as a model for rapid development more applicable to African states than the West, and how the architects negotiated their professional practice in relation to the Israeli Foreign Ministry agendas, the African commissioners' expectations, and the international disciplinary discourse on modern architecture. I argue that while architectural modernism was promoted in the West as the International Style, Israeli architects translated it to the African context by imbuing it with nation-building qualities such as national cohesion, labor mobilization, skill acquisition and population dispersal. Based on their labor-Zionism settler-colonial experience, -

Fine Judaica, to Be Held May 2Nd, 2013

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts & autograph Letters including hoLy Land traveL the ColleCtion oF nathan Lewin, esq. K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, m ay 2nd, 2013 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 318 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . PRINTED BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, & AUTOGRAPH LETTERS INCLUDING HOLY L AND TR AVEL THE COllECTION OF NATHAN LEWIN, ESQ. ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, May 2nd, 2013 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, April 28th - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, April 29th - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Tuesday, April 30th - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, May 1st - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Pisgah” Sale Number Fifty-Eight Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. Insel Client Accounts: S. Rivka Morris Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. (Consultant) Printed Books & Manuscripts: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial & Graphic Art: Abigail H. -

Appendices (1936-1937)

ANNIVERSARIES AND OTHER CELEBRATIONS UNITED STATES July 7, 1935. New York City: Seventy-fifth anniversary of birth of ABRAHAM CAHAN, editor of Jewish Daily Forward. July 7, 1935. Seattle, Wash.: Celebration of eightieth anniversary of birth of SAMUEL R. STERN, judge, veteran member of B'nai B'rith. July 9, 1935. Brooklyn, N. Y.: Sixty-fifth birthday anniversary of MITCHELL MAY, New York State Supreme Court Judge. July 12, 1935. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Celebration of seventy-fifth anniver- sary of birth of HENRY KAUFMANN, philanthropist. July 28, 1935. Portland, Ore.: Eightieth anniversary of birth of I. BROMBERG, communal worker. October 1, 1935. Cincinnati, Ohio: Celebration of seventy-fifth an- niversary of birth of N. HENRY BECKMAN, communal leader. October 18-19, 1935. Baltimore, Md.: Celebration of twentieth anniversary of ministry of MORRIS S. LAZARON, as rabbi of Baltimore Hebrew Congregation. October 24, 1935. Cincinnati, Ohio: Celebration of eighty-fifth an- niversary of birth of CHARLES SHOHL, communal leader. October 24, 1935. Chicago, 111.: Twentieth anniversary of service on the bench of SAMUEL ALSCHULER, Judge of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals, celebrated by the Chicago Bar Association. October 25, 1935. Brooklyn, N. Y.: Celebration of twentieth anniver- sary of the JEWISH COMMUNAL CENTER OF FLATBUSH. October 25, 1935. Jackson, Mich.: Celebration of seventy-fifth an- niversary of founding of TEMPLE BETH ISRAEL. October, 1935. Minneapolis, Minn.: Celebration of eightieth anniver- sary of birth of MRS. HENRY WEISKOPF, communal worker. November 12, 1935. New York City: Sixtieth anniversary of birth of NATHAN RATNOFF, medical director of Beth Israel Hospital and of Jewish Maternity Hospital.