•Mt Mtumtzmm Op Jwhjh Zx Csmm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5: Ceylon: Trade Or Territory?

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/59468 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Odegard, Erik Title: Colonial careers : Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen, Rijckloff Volckertsz. van Goens and career-making in the Seventeenth-Century Dutch Empire Date: 2018-01-18 121 5. Ceylon: Trade or Territory? Van Goens and Ceylon as a challenge to Batavia’s dominance, 1655 -1670 In 1655-1656 Van Goens briefly returned in the Netherlands for the first time in twenty-seven years. Using his previous experience as a diplomat, merchant and soldier, he was able to convince the VOC directors to change course towards a more aggressive expansionist policy in South Asia. By 1656 he was set to return to Asia at the head of a large fleet, with the aim of finally ejecting the Portuguese from Ceylon, Malabar and, if at all possible, Diu. This proved to be the start of an entanglement with Ceylon that would last until 1675, when he returned to Batavia. Ceylon captivated Van Goens and, even in Batavia, the major debates centered on what place the island should take in the VOC’s now sizable Asian domains, and what th e official policy should be in relation to the interior kingdom of Kandy. This chapter will focus on the first fifteen years of this period, 1655-1670, when Van Goens was to a large extent able to dictate the VOC’s policies on Ceylon and Southern India. While on Ceylon, Van Goens faced three questions: how should the VOC rule its parts of the island? What should be the relationship between the Ceylon government and the surrounding polities, both on Ceylon with Kandy, as well as with the neighboring states in Southern India? Thirdly, how should Ceylon relate to the neighboring VOC commands of Surat, Vengurla, Coromandel and Bengal? Van Goens came up with answers to all these questions and attempted to put them into practice, thus shaping the VOC’s posture in the area for the next century and more. -

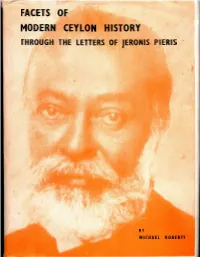

Facets-Of-Modern-Ceylon-History-Through-The-Letters-Of-Jeronis-Pieris.Pdf

FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS BY MICHAEL ROBERT Hannadige Jeronis Pieris (1829-1894) was educated at the Colombo Academy and thereafter joined his in-laws, the brothers Jeronis and Susew de Soysa, as a manager of their ventures in the Kandyan highlands. Arrack-renter, trader, plantation owner, philanthro- pist and man of letters, his career pro- vides fascinating sidelights on the social and economic history of British Ceylon. Using Jeronis Pieris's letters as a point of departure and assisted by the stock of knowledge he has gather- ed during his researches into the is- land's history, the author analyses several facets of colonial history: the foundations of social dominance within indigenous society in pre-British times; the processes of elite formation in the nineteenth century; the process of Wes- ternisation and the role of indigenous elites as auxiliaries and supporters of the colonial rulers; the events leading to the Kandyan Marriage Ordinance no. 13 of 1859; entrepreneurship; the question of the conflict for land bet- ween coffee planters and villagers in the Kandyan hill-country; and the question whether the expansion of plantations had disastrous effects on the stock of cattle in the Kandyan dis- tricts. This analysis is threaded by in- formation on the Hannadige- Pieris and Warusahannadige de Soysa families and by attention to the various sources available to the historians of nineteenth century Ceylon. FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS MICHAEL ROBERTS HANSA PUBLISHERS LIMITED COLOMBO - 3, SKI LANKA (CEYLON) 4975 FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 This book is copyright. -

Altea Gallery

Front cover: item 32 Back cover: item 16 Altea Gallery Limited Terms and Conditions: 35 Saint George Street London W1S 2FN Each item is in good condition unless otherwise noted in the description, allowing for the usual minor imperfections. Tel: + 44 (0)20 7491 0010 Measurements are expressed in millimeters and are taken to [email protected] the plate-mark unless stated, height by width. www.alteagallery.com (100 mm = approx. 4 inches) Company Registration No. 7952137 All items are offered subject to prior sale, orders are dealt Opening Times with in order of receipt. Monday - Friday: 10.00 - 18.00 All goods remain the property of Altea Gallery Limited Saturday: 10.00 - 16.00 until payment has been received in full. Catalogue Compiled by Massimo De Martini and Miles Baynton-Williams To read this catalogue we recommend setting Acrobat Reader to a Page Display of Two Page Scrolling Photography by Louie Fascioli Published by Altea Gallery Ltd Copyright © Altea Gallery Ltd We have compiled our e-catalogue for 2019's Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Fair in two sections to reflect this year's theme, which is Firsts The catalogue starts with some landmarks in printing history, followed by a selection of highlights of the maps and books we are bringing to the fair. This year the fair will be opened by Stephen Fry. Entry on that day is £20 but please let us know if you would like admission tickets More details https://www.firstslondon.com On the same weekend we are also exhibiting at the London Map Fair at The Royal Geographical Society Kensington Gore (opposite the Albert Memorial) Saturday 8th ‐ Sunday 9th June Free admission More details https://www.londonmapfairs.com/ If you are intending to visit us at either fair please let us know in advance so we can ensure we bring appropriate material. -

Jan Van Riebeeck, De Stichter Van GODEE MOLSBERGEN Hollands Zuid-Afrika

Vaderlandsche cuituurgeschiedenis PATRIA in monografieen onder redactie van Dr. J. H. Kernkamp Er is nagenoeg geen Nederlander, die niet op een of andere wijze door zijn levensonderhoud verbonden is met ons koloniaal rijk overzee, en die niet belang- stelling zou hebben voor de mannen, die dit rijk hielpen stichten. Dr. E. C. Een deter is Jan van Riebeeck, de Stichter van GODEE MOLSBERGEN Hollands Zuid-Afrika. Het zeventiende-eeuwse avontuurlijke leven ter zee en te land, onder Javanen, Japanners, Chinezen, Tonkinners, Hotten- Jan van Riebeeck totten, de koloniale tijdgenoten, hun voortreffelijke daden vol moed en doorzicht, hun woelen en trappen en zijn tijd oxn eer en geld, het zeemans lief en leed, dat alles Een stuk zeventiende-eeuws Oost-Indie maakte hij mee. Zijn volharding in het tot stand brengen van wat van grote waarde voor ons yolk is, is spannend om te volgen. De zeventiende-eeuwer en onze koloniale gewesten komen door dit boek ons nader door de avonturen. van de man, die blijft voortleven eeuwen na zijn dood in zijn Stichting. P. N. VAN KAMPEN & LOON N.V. AMSTERDAM MCMXXXVII PAT M A JAN VAN RIEBEECK EN ZIJN TIJD PATRIA VADERLANDSCHE CULTUURGESCHIEDENIS IN MONOGRAFIEEN ONDER REDACTIE VAN Dr. J. H. KERNKAMP III Dr. E. C. GODEE MOLSBERGEN JAN VAN RIEBEECK EN ZIJN TIJD Een stuk zeventiende-eeuws Oost-Indie 1937 AMSTERDAM P. N. VAN KAMPEN & ZOON N.V. INHOUD I. Jeugd en Opvoeding. Reis naar Indio • • . 7 II. Atjeh 14 III. In Japan en Tai Wan (= Formosa) .. .. 21 IV. In Tonkin 28 V. De Thuisreis 41 VI. Huwelijk en Zeereizen 48 VII. -

Encounters on the Opposite Coast European Expansion and Indigenous Response

Encounters on the Opposite Coast European Expansion and Indigenous Response Editor-in-Chief George Bryan Souza (University of Texas, San Antonio) Editorial Board Catia Antunes (Leiden University) Joao Paulo Oliveira e Costa (Cham, Universidade Nova de Lisboa) Frank Dutra (University of California, Santa Barbara) Kris Lane (Tulane University) Pedro Machado (Indiana University, Bloomington) Malyn Newitt (King’s College, London) Michael Pearson (University of New South Wales) VOLUME 17 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/euro Encounters on the Opposite Coast The Dutch East India Company and the Nayaka State of Madurai in the Seventeenth Century By Markus P.M. Vink LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Skirmishes between the Dutch and Nayaka troops at Tiruchendur during the ‘punitive expedition’ of 1649. Mural painting by Sri Ganesan Kalaikkoodam. Photo provided by Patrick Harrigan. Sri Subrahmanya Swamy Devasthanam, Tiruchendur. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vink, Markus P. M. Encounters on the opposite coast : the Dutch East India Company and the Nayaka State of Madurai in the seventeenth century / by Markus P.M. Vink. pages cm. -- (European expansion and indigenous response, ISSN 1873-8974 ; volume 17) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-27263-7 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-27262-0 (e-book) 1. Nederlandsche Oost-Indische Compagnie--History--17th century. 2. Netherlands--Commerce--India--Madurai (District)-- History--17th century. 3. Madurai (India : District)--Commerce--Netherlands--History--17th century. 4. Netherlands--Relations--India--Madurai (District) 5. Madurai (India : District)--Relations--Netherlands. 6. Acculturation--India--Madurai (District)--History--17th century. 7. Culture conflict--India--Madurai (District)--History--17th century. -

CONTENTS Chapter Preface Introduction 1

CONTENTS Chapter Preface Introduction 1. Sri Lanka 2. Prehistoric Lanka; Ravana abducts Princess Sita from India.(15) 3 The Mahawamsa; The discovery of the Mahawamsa; Turnour's contribution................................ ( 17) 4 Indo-Aryan Migrations; The coming of Vijaya...........(22) 5. The First Two Sinhala Kings: Consecration of Vijaya; Panduvasudeva, Second king of Lanka; Princess Citta..........................(27) 6 Prince Pandukabhaya; His birth; His escape from soldiers sent to kill him; His training from Guru Pandula; Battle of Kalahanagara; Pandukabhaya at war with his uncles; Battle of Labu Gamaka; Anuradhapura - Ancient capital of Lanka.........................(30) 7 King Pandukabhaya; Introduction of Municipal administration and Public Works; Pandukabhaya’s contribution to irrigation; Basawakulama Tank; King Mutasiva................................(36) 8 King Devanampiyatissa; gifts to Emporer Asoka: Asoka’s great gift of the Buddhist Doctrine...................................................(39) 9 Buddhism established in Lanka; First Buddhist Ordination in Lanka around 247 BC; Mahinda visits the Palace; The first Religious presentation to the clergy and the Ordination of the first Sinhala Bhikkhus; The Thuparama Dagoba............................ ......(42) 10 Theri Sanghamitta arrives with Bo sapling; Sri Maha Bodhi; Issurumuniya; Tissa Weva in Anuradhapura.....................(46) 11 A Kingdom in Ruhuna: Mahanaga leaves the City; Tissaweva in Ruhuna. ...............................................................................(52) -

The Interface Between Buddhism and International Humanitarian Law (Ihl)

REDUCING SUFFERING DURING CONFLICT: THE INTERFACE BETWEEN BUDDHISM AND INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW (IHL) Exploratory position paper as background for 4th to 6th September 2019 conference in Dambulla, Sri Lanka Peter Harvey (University of Sunderland, Emeritus), with: Kate Crosby (King’s College, London), Mahinda Deegalle (Bath Spa University), Elizabeth Harris (University of Birmingham), Sunil Kariyakarawana (Buddhist Chaplain to Her Majesty’s Armed Forces), Pyi Kyaw (King’s College, London), P.D. Premasiri (University of Peradeniya, Emeritus), Asanga Tilakaratne (University of Colombo, Emeritus), Stefania Travagnin (University of Groningen). Andrew Bartles-Smith (International Committee of the Red Cross). Though he should conquer a thousand men in the battlefield, yet he, indeed, is the nobler victor who should conquer himself. Dhammapada v.103 AIMS AND RATIONALE OF THE CONFERENCE This conference, organized by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in collaboration with a number of universities and organizations, will explore correspondences between Buddhism and IHL and encourage a constructive dialogue and exchange between the two domains. The conference will act as a springboard to understanding how Buddhism can contribute to regulating armed conflict, and what it offers in terms of guidance on the conduct of, and behavior during, war for Buddhist monks and lay persons – the latter including government and military personnel, non-State armed groups and civilians. The conference is concerned with the conduct of armed conflict, and not with the reasons and justifications for it, which fall outside the remit of IHL. In addition to exploring correspondences between IHL and Buddhist ethics, the conference will also explore how Buddhist combatants and communities understand IHL, and where it might align with Buddhist doctrines and practices: similarly, how their experience of armed conflict might be drawn upon to better promote IHL and Buddhist principles, thereby improving conduct of hostilities on the ground. -

Maps in De Heere's Journal

Maps in De Heere’s Journal Cartographic Reflections of VOC Policy on Ceylon, 1698 Clemens Deimann Research Master Thesis 1351052 Prof. Dr. Michiel van Groesen [email protected] 13-07-2018 Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................ iii List of Figures and Tables .................................................................................................. iv Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 Historiography ................................................................................................................. 1 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1 – A Mighty Island ............................................................................................... 9 Ceylon and its position in the VOC ............................................................................... 10 The Territorial Ambitions of Van Goens ....................................................................... 12 The VOC in the Late Seventeenth Century ................................................................... 20 Policy on Sri Lanka ....................................................................................................... 22 Chapter 2 – The Journal .................................................................................................... -

GEOGRAPHY Grade 11 (For Grade 11, Commencing from 2008)

GEOGRAPHY Grade 11 (for Grade 11, commencing from 2008) Teachers' Instructional Manual Department of Social Sciences Faculty of Languages, Humanities and Social Sciences National Institute of Education Maharagama. 2008 i Geography Grade 11 Teachers’ Instructional Manual © National Institute of Education First Print in 2007 Faculty of Languages, Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Social Science National Institute of Education Printing: The Press, National Institute of Education, Maharagama. ii Forward Being the first revision of the Curriculum for the new millenium, this could be regarded as an approach to overcome a few problems in the school system existing at present. This curriculum is planned with the aim of avoiding individual and social weaknesses as well as in the way of thinking that the present day youth are confronted. When considering the system of education in Asia, Sri Lanka was in the forefront in the field of education a few years back. But at present the countries in Asia have advanced over Sri Lanka. Taking decisions based on the existing system and presenting the same repeatedly without a new vision is one reason for this backwardness. The officers of the National Institute of Education have taken courage to revise the curriculum with a new vision to overcome this situation. The objectives of the New Curriculum have been designed to enable the pupil population to develop their competencies by way of new knowledge through exploration based on their existing knowledge. A perfectly new vision in the teachers’ role is essential for this task. In place of the existing teacher-centred method, a pupil-centred method based on activities and competencies is expected from this new educa- tional process in which teachers should be prepared to face challenges. -

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert PhD 2016 Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, Politics and Philosophy Manchester Metropolitan University 2016 Abstract: The thesis argues that the telephone had a significant impact upon colonial society in Sri Lanka. In the emergence and expansion of a telephone network two phases can be distinguished: in the first phase (1880-1914), the government began to construct telephone networks in Colombo and other major towns, and built trunk lines between them. Simultaneously, planters began to establish and run local telephone networks in the planting districts. In this initial period, Sri Lanka’s emerging telephone network owed its construction, financing and running mostly to the planting community. The telephone was a ‘tool of the Empire’ only in the sense that the government eventually joined forces with the influential planting and commercial communities, including many members of the indigenous elite, who had demanded telephone services for their own purposes. However, during the second phase (1919-1939), as more and more telephone networks emerged in the planting districts, government became more proactive in the construction of an island-wide telephone network, which then reflected colonial hierarchies and power structures. Finally in 1935, Sri Lanka was connected to the Empire’s international telephone network. One of the core challenges for this pioneer work is of methodological nature: a telephone call leaves no written or oral source behind. -

A Bibliography of 17Th Century German Imprints in Denmark and the Duchies of Schleswig-Holstein

A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF 17TH CENTURY GERMAN IMPRINTS IN DENMARK AND THE DUCHIES OF SCHLESWIG-HOLSTEIN By P. M. MITCHELL Volume 1 UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES 1969 UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS PUBLICATIONS Library Series, 28 A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF 17TH CENTURY GERMAN IMPRINTS IN DENMARK AND THE DUCHIES OF SCHLESWIG^HOLSTEIN By P. M. MITCHELL Volume 1 UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES 1969 COPYRIGHT 1969 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES Library of Congress catalog card number : 66-64214 PRINTED IN LAWRENCE, KANSAS, U.S.A. BY THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS PRINTING SERVICE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IN PREPARING THIS BIBLIOGRAPHY I HAVE BENEFITED FROM THE ASSISTANCE AND GOOD OFFICES OF MANY INDIVIDUALS AND INSTITUTIONS. MY GREATEST DEBT IS TO THE ROYAL LIBRARY IN COPENHAGEN, WHERE, FROM FIRST TO LAST, I HAVE DRAWN ON THE COUNSELS AND ENVIABLE HISTORICAL KNOWLEDGE OF DR. RICHARD PAULLI. MESSRS. PALLE BIRKE- LUND, ERIK DAL, AND MOGENS HAUGSTED AS WELL AS MANY OTHER MEMBERS OF THE STAFF OF THE ROYAL LIBRARY CHEERFULLY SOUGHT TO MEET MY SPECIAL NEEDS FOR A DECADE. THE COOPERATION OF DR. OTFRIED WEBER, MR. WOLFGANG MERCKENS, AND MR. KARL-HEINZ TIEDEMANN OF THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF KIEL HAS BEEN EXEM• PLARY. DR. OLAF KLOSE OF THE SCHLESWIG-HOLSTEINISCHE LANDESBIBLIOTHEK KINDLY ARRANGED MY VISITS TO SEVERAL PRIVATE LIBRARIES, WHERE I WAS HOSPITABLY RECEIVED. I HAVE ENJOYED SPECIAL PRIVILEGES NOT ONLY IN COPENHAGEN AND KIEL BUT ALSO AT THE LIBRARY OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM, THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF COPEN• HAGEN, THE HERZOG AUGUST BIBLIOTHEK IN WOLFENBÜTTEL, THE ROYAL LIBRARY IN STOCKHOLM, AND THE STAATSBIBLIOTHEK IN MUNICH. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal Philips Galle (1537-1612): engraver and print publisher in Haarlem and Antwerp Sellink, M.S. 1997 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Sellink, M. S. (1997). Philips Galle (1537-1612): engraver and print publisher in Haarlem and Antwerp. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 08. Oct. 2021 MANFRED SELLINK PHILIPS GALLE (1537-1612) ENGRAVER AND PRINT PUBLISHER IN HAARLEM AND ANTWERP li NOTES/APPENDICES Notes Introduction 1. &igg5 1971, For further references on our knowledge of Netherlandish printmaking m general and Philips Galle in particular, see chapter 1, notes 32-33 and chapter 4, note 1. 2. Van den Bemden 1863. My research of a print acquired by the Rijksprentenkabinet in 1985 resulted in ail article on the collaboration between the Galle family and Johannes Stradanus on an abortive attempt to pro• duce a series of engraved illustrations for Dante's Divina Commedia (Seliink 1987) 3.