Bennett, Breen and the Birdman of Alcatraz: a Case Study of Collaborative Censorship Between the Production Code Administration and the Federal Bureau of Prisons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Economics of Educational Rehabilitation Jon M

The Economics of Educational Rehabilitation Jon M. Taylor Washington, D.C., December 1, 1988 - The Criminal Justice system is starvedfor resources and it is the lack ofadequate funding, rather than constitutional safeguards like the exclusionary rule or the Miranda warning, that is hindering law enforcement efforts, according to a study released today by the American Bar Associa- tion ... The report points out that the public should understand and accept that the Criminal Justice system alone cannot eliminate the crime problem. However, the principal complaint ofCriminal Justice of- ficials was that "they were not given the resources to do what they could do well ... " It warns that the answers to this growing problem are not "so simple as merely making more arrests and imposing longer prison sentences" and urges immediate action be taken "to rethink our strategies ... " Over the past few years, several national surveys conducted by news or- ganizations have reported that an overwhelming number of Americans feel that drugs/crime is the nation's most serious problem. In fact, the fear of crime has been reported to be ournation' s most pressing social problem for nearly a decade. Society's demand for action has, in part, resulted in the rewriting of sentencing laws anq probation guidelines in most states. This has further resulted in longer prison sentences for those incarcerated, and a bulging, growing, and recycling national prison population. America is rethinking its prison system. The impetus is cold, hard economics: the growing expense of corrections has ballooned out of control. But in the search for ways to cut costs, corrections authorities also are exploring new means of punishing lawbreakers that may achieve a long-elusive social goal as well: a greater degree of rehabilitation. -

Waterbirds of Alcatraz (PDF)

National Park Service Waterbirds of Alcatraz U. S. Department of Interior Golden Gate National Recreation Area The Birds Return Alcatraz takes its name from the word, alcatraces, or seabirds, from the early Spanish explorers. Generations of seabirds occupied the island until it became a military fortress in the 1850’s. For the next hundred years, hardly any birds remained as the human activities of the fortress, military prison, and then federal penitentiary kept them away. Even The Birdman of Alcatraz, Robert Stroud, didn’t have any birds here. When the cellhouse closed in 1963, the lack of human disturbance and land predators, as well as island topography and location, led to the return of the birds. Today, this National Historic Landmark is a haven for over 5,000 nesting birds. Creating Their Niche When the U.S. Army dynamited the island to build the fortress, the resulting steep cliffs and tide pools gradually became wildlife habitat. Garden plants that had been tended during the federal penitentiary years grew into dense thickets of cover for sensitive birds. Nests are even tucked within the rubble and concrete pipes left over from the era when correctional officers and their families lived here. A diversity of wildlife Bancroft Library, Eadweard Muybridge Collection finds their niche within these man-made U.S. Army soldiers, Alcatraz 1869 habitats. Birds of Warning Alcatraz waterbirds feed nearby when alert us to impacts to the ecosystem their chicks are helpless and growing that may affect our health as well. On fast. Most dive in the bay or wade along Alcatraz, National Park Service and PRBO shorelines and tide pools. -

Issue 12.Pdf

w Welcome This is issue twelve LPM has entered its third year of existence and there are some changes this year. Instead of releasing an issue every two months we are now a quarterly magazine, so a new issue is released every three months. We also are happy to welcome Annie Weible to our writing staff, we are psyched that she has joined our team. We will continue to bring you interesting articles and amazing stories. Paranormal - true crime- horror In this Issue The Legends of Alcatraz 360 Cabin Update Part two The Dybbuk Box The Iceman Aleister Crowley The Haunting of Al Capone Horror Fiction The visage of Alcatraz conjures visions of complete and utter isolation. The forlorn wails of intrepid seagulls beating against the craggy shore. A stoic reminder of the trials of human suffering, the main prison rises stark against the roiling San Francisco Bay. The Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary began its storied history in 1910 as a United States Army prison before transforming into a federal prison in 1934. Since its inception, Alcatraz held the distinction of being one of America’s toughest prisons, often being touted as “escape proof”. During its time as an active prison, Alcatraz held some of the most problematic prisoners. Notable characters held in Alcatraz includes; Al Capone, Machine Gun Kelley and Robert Stroud, among just a few. Alphonse Gabriel Capone, also known as Scarface, was an American gangster. Scarface was known for his brutality following the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago in which seven rival gang members were gunned down by Capone’s men. -

Neurobehavioral Disorders Locked in Alcatraz: Case Reports on Three Famous Inmates

DOI: 10.1590/0004-282X20150075 ARTICLEHISTORICAL NOTE Neurobehavioral disorders locked in Alcatraz: case reports on three famous inmates Distúrbios neurocomportamentais presos em Alcatraz: relatos de caso em três famosos presidiários Hélio A. G. Teive, Luciano de Paola ABSTRACT The Alcatraz prison, with its picturesque surroundings and fascinating life stories of its inmates, has been the subject of a number of films and publications. The authors take a closer look at the biographies of “Al Capone”, Robert “Birdman” Stroud and “Mickey” Cohen. These legendary American mobsters shared not only a history at “The Rock”, but also a history of neuropsychiatric diseases, ranging from neurosyphilis to anti-social, borderline and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Keywords: neurosyphilis, personality disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, criminal behavior. RESUMO A prisão de Alcatraz, com sua atmosfera pitoresca e as fascinantes histórias de seus prisioneiros, foi objeto de vários filmes e publicações. Os autores focam nas biografias de “Al Capone”, Robert “Birdman” Stroud and “Mickey” Cohen. Estes legendários gangsteres americanos tem em comum não apenas suas penas cumpridas no “Rochedo”, mas também uma história de doenças neuropsiquiátricas, de neurosífilis a personalidades anti-sociais, “borderline” e obsessivo-compulsivas. Palavras-chave: neurosífilis, transtorno de personalidade, distúrbio obsessivo-compulsivo, comportamento criminal. Criminal behavior and violence are considered as world- including the very notorious American gangsters Alphonse wide public health problems1. Criminal behavior has neuro- “Scarface” Capone, Robert “Birdman” Stroud, and Meyer H. biological basis. Recent studies have focused in this issue, M. “Mickey” Cohen6,7. emphasizing biological and psycho social deficits1,2. Different types of personality disorders, as borderline and antisocial personality disorder, have been related to violence and crimi- ALPHONse “AL” CaPONE nal behavior1,2,3,4,5. -

Statement of Significance

Alcatraz Island Golden Gate National Recreation Area Statement Of Significance Alcatraz Island was listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in 1976 and was designated a National Historic Landmark (NHL) in 1986. The National Register nomination describes the significance of Alcatraz Island: “Alcatraz is an island in San Francisco Bay which is of national historical significance in the categories of military history and social history (penology). During the mid-19th Century it was an impressive fortress guarding, along with Fort Point and, later, Angel Island, the entrance to San Francisco Bay. As a fortress, it was as nearly impregnable as technology of the time could make it – an “American Gibraltar” – and it was crowned with a brick/masonry “Citadel” which may have been unique in the annals of American military architecture. In later years it served as a military prison, and in more recent times became a Federal penitentiary and one of America’s most famous penal institutions, with a reputation rivaling France’s Devil’s Island. As a Federal prison, it housed some of America’s most dangerous criminals, those whom it was believed were too unmanageable for incarceration in other Federal prisons. Its location in the Bay rendered Alcatraz nearly escape-proof” (Chappell 1976). The statement of significance included with the NHL nomination states: “Alcatraz Island has been the site of events that have had an important impact on the nation as a whole from before the Civil War through an Indian Occupation of the 1970s. Its significance in the area of military history, social history (penology), and maritime commerce is enhanced by the integrity of the resource which follows from the fact that access to the island has been strictly limited by the U.S. -

ALCATRAZ – by Jane Bouterse an ISLAND CALLED HOME

ALCATRAZ – by Jane Bouterse AN ISLAND CALLED HOME ou know about it. The legends began Pelican / Mockingbird / Raven / is usually defined as meaning “pelican” or in 1850 and have only grown, so Nightingale “strange bird.” Ywhether by word of mouth, printed page, internet screen, mass media or Your discoveries will be many and The Alcatraz Island, before it became personal visit—you know about that 12 surprising. You will be even more amazed at home to a prison, was used as what? acre, “mystery-cloaked” rock in the middle of how “close to home” this legendary location San Francisco Bay—ALCATRAZ. But how happens to be to some Texarkana residents. Airport / Military site / Holiday resort / much do you really know? Just for fun, grab To understand completely requires starting National park a pen or pencil, circle your answers to the at the beginning—1775. That was the year questions , then read to learn the accuracy Spanish explorer Juan Manual de Ayala What was the prison’s nickname? of your choices: first sailed into what became known as San Francisco Bay. Ayala and company mapped The Bridge / The Brick / The Rock / The The name of the prison comes from a the bay and named one of its three islands Stone Spanish word Alcatraces. What does the Alcatraces, which has become Anglicized word mean? to Alcatraz. Although the exact meaning of According to the internet’s “A Brief the word remains controversial, Alcatraz History of Alcatraz,” in 1850 when California Rubble that remained after Indian occupation. 34 ALT Magazine For over 80 years, 1850 until was booming, a presidential order set the 1933, the U. -

S3-Ms Russel-English-Report

Hello S3, we have spent the last few weeks working through all these reading tasks on Alcatraz to build up quite a large body of knowledge about it. The final task is to write a report and as I think this would be tricky to do it live lessons, I would like you to do it as part of your home learning. If you have been attending the live classes, then skip to the end with instructions on how to write the report. If you have missed class, then slowly work through the reading tasks at a pace that suits you. There is a lot of work in here so I am not expecting you to complete it all. Email any completed work to me at [email protected] Hopefully see you soon! Ms Russell ALCATRAZ The Big Picture • As a class, we will read and work through this unit on ‘Alcatraz.’ • Once the unit is completed, you will have a lot of information on Alcatraz and you will be asked to write a report on this topic. • This report may be one of the essays chosen for your folio, so make sure you make it as detailed and interesting as possible. Skills During this unit you will develop your skills in Reading, Writing, Listening and Talking. Reading • Before and as I read, I can apply strategies and use resources independently to help me find the information I need. LIT 4-13a • Using what I know about the features of different types of texts, I can find, select, sort, summarise, link and use information from different sources. -

Working in the Belly of the Beast: the Productive Intellectual Labor of Us Prison Writers, 1929-2007

WORKING IN THE BELLY OF THE BEAST: THE PRODUCTIVE INTELLECTUAL LABOR OF US PRISON WRITERS, 1929-2007 by Nathaniel Zachery Heggins Bryant BA, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2005 MA, University of Tennessee, 2008 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathaniel Zachery Heggins Bryant It was defended on May 19, 2014 and approved by Sabine von Dirke, Associate Professor, Department of German Nicholas Coles, Associate Professor, Department of English David Bartholomae, Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Philip Smith, Associate Professor, Department of English ii Copyright © by Nathaniel Zachery Heggins Bryant 2014 iii WORKING IN THE BELLY OF THE BEAST: THE PRODUCTIVE INTELLECTUAL LABOR OF US PRISON WRITERS, 1929-2007 Nathaniel Zachery Heggins Bryant, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 This dissertation seeks to revise and expand notions of US prison writing beyond the normative categories of “literature” by examining the compositional and rhetorical efforts of US prison writers working from 1929 to 2007. I situate certain modes, discourses, and texts produced by prisoners—scientific research, jailhouse legal work, letter-writing, revolutionary polemic, and testimonial writing—within a larger rubric of what I call “productive intellectual labor.” The project draws on Marxist debates to define each part of that term and employs the work of Michel Foucault to contextualize prevailing historical notions regarding penal labor, the evolution of punishment, and discursive trends of those writing back to power. -

The Resistable Rise and Predictable Fall of the US Supermax

mo nt hlyreview.o rg http://monthlyreview.org/2009/11/01/the-resistable-rise-and-predictable-fall-of-the-u-s-supermax The Resistable Rise and Predictable Fall of the U.S. Supermax :: Monthly Review Stephen F. Eisenman Stephen F. Eisenman is prof essor of art history at Northwestern University and the editor and principle author of Nineteenth Century Art (New York: Thames & Hudson). Throughout 2008–09, Eisenman worked with a group of Chicago artists, activists, and lawyers to end torture at Tamms supermax prison. In a recent article entitled “The Penal State in an Age of Crisis ” (Monthly Review, June 2009), Hannah Holleman, Robert W. McChesney, John Bellamy Foster, and R. Jamil Jonna sought to account f or the surprising stability of civilian government spending (non-def ense government consumption and investment) as a percentage of GDP during a period, roughly 1970 to the present, when the power of capital over labor increased, inequality grew, and cuts in government programs f or the poor and working class continued more or less without abatement.1 One solution to the paradox, the authors persuasively argued, was the growth in spending f or “the penal state,” a political regime marked by the mass incarceration of the poor and the vulnerable who posed risks to the stability of the prevailing economic and social order. Indeed, the incarcerated population of the United States has grown markedly in the last three decades, f rom approximately 221 per 100,000 of population in 1980, to 762 per 100,000 in 2008. The United States now has by f ar the highest incarceration rate in the world (over six times higher than Britain’s or China’s and twelve times higher than Japan’s), an incarcerated population of 2.3 million, and a total correctional population (in prison or jail, or on probation) of 7.3 million.2 In other words, civilian government spending has remained constant during a period of capitalist-class consolidation, in part because an increasing proportion of that expenditure has gone to maintaining a penal state that disciplines the poor. -

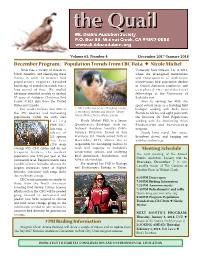

Duplicate Color Decc 17-Jan 18 Quail

Volume 63, Number 4 December 2017-January 2018 December Program : Population Trends from CBC Data ✦ Nicole Michel Birds face a variety of threats in University, New Orleans, LA, in 2012, North America, and identifying these where she investigated mechanisms threats in order to conserve bird and consequences of understory p opulations re quires detaile d insectivorous bird population decline knowledge of population trends over a in Central American rainforests, and long period of time. We studied c o m p l e t e d t w o p o s t d o c t o r a l advanced statistical models to analyze fellowships at the University of 52 years of Audubon Christmas Bird Saskatchewan. Count (CBC) data from the United Prior to earning her PhD, she States and Canada. spent several years as a traveling field Our results indicate that 60% of L: 2015 CBC; Top Center: Peregrine Falcon, biologist working with birds from the 497 species had increasing a recovering species; and Bottom Center: Florida to Alaska, and eight years with Nicole Michel, Nicole Michel photos populations within the study area the Institute for Bird Populations d u r i n g Nicole Michel, PhD, is a Senior working with the Monitoring Avian 1966–2017. Quantitative Ecologist with the Productivity and Sur vivorship A m o n g a National Audubon Society’s (NAS) program. s u b s e t o f Science Division, based in San Nicole loves travel, live music, 212 species Francisco, CA. Nicole joined NAS in Broadway shows, and hanging out that have December 2015, where she is with her (indoor) cat. -

Self-Guiding Information "You Are Entitled to Eood, Clothing and Medical Attention

ENGL SH SELF-GUIDING INFORMATION "YOU ARE ENTITLED TO EOOD, CLOTHING AND MEDICAL ATTENTION. ANYTHING H is A privilege; Number 5, Institution Rules & Regulations, USP Alcatraz I I " , SHELTER, ,SE YOU GET This rule was one of the realities of Ufe inside the walls of United States Penitentiary, Alcatraz Island. The subject of many movies and books. Alcatraz has become a symbol of America's dark side. From fiction rather than fact, we have stories of the prison and of some of . V the men who lived in its cells— ' • í • t Al "Scarface" Capone and Robert ' V'l.rMÍTii', • \f' V . Stroud, the "Birdman of Alcatraz," for example. The truth of Alcatraz has often been overlooked, lost in the fog of its myths. Use this brochure to discover some of Alcatraz s true stories. I r^i Ul ALCATRAZ FORT For thousands of years, Alcatraz was a lonely In 1850, a military board proposed island, occasionally visited, perhaps, by a three-point defensive strategy for San Ohlone and Miwokindians. Between the Francisco Bay. This approach required that a time the Spanish settled the Bay Area (1776) massive brick fort be built on each side of the and the Yankees took over from the Mexicans Golden Gate. Alcatraz, directly in line with (1846), the island was noted on maps but was ships entering the harbor, was selected as otherwise unused. The last Mexican governor the site of the third, smaller fortification. An of California planned to erect a lighthouse army Board of Engineers surveyed the island on Alcatraz, but before it could be built, in 1852, and by 1853, construction had begun. -

Commencement

Commencement Westlake High School 2021 Eanes Independent School District Westlake High School Commencement 2021 Frank Erwin Center University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas Monday, May 24, 2021 7:00 p.m. Class of 2021 Commencement Program MASTER OF CEREMONIES…………………….………………….….Audrey Lingan Student Body Vice President PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE…....................................Abhinav Rachakonda Senior Class Vice President NATIONAL ANTHEM…….....................Westlake High School Madrigals Ed Snouffer, Director WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS……….........................Audrey Lingan Student Body Vice President BOARD OF TRUSTEES’ MESSAGE…………...……...……...John Havenstrite Eanes ISD School Board President 2020-21 SUPERINTENDENT’S MESSAGE……..……………..………...Dr. Tom Leonard CONFIRMATION OF GRADUATES..………………...…..….…….Steve Ramsey Principal ACCEPTANCE OF THE CLASS...……………………………..….Dr. Tom Leonard Superintendent PRESENTATION OF GRADUATES Jocelyn Bixler, Teacher SALUTATORY ADDRESS……….………………………………..……Nolan Amblard Salutatorian Lee Bergen, Teacher James Baker, Teacher VALEDICTORY ADDRESS / CLASS OF 2021 MESSAGE..……….Felix Chen Valedictorian / Student Body President Melinda Darrow, Teacher Cathy Cluck, Teacher CONGRATULATIONS….....................................................Ellie Churchill Class of 2021 President ALMA MATER……..........Westlake High School Band and Class of 2021 Student messages offered at this evening’s graduation ceremony are private expressions of the students offering the messages, and are not endorsed or sponsored by the Eanes Independent