Micnsilms Intemationcil 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silence and Writing in La Vie De Saint Alexis, Le Conte Du Graal, and Le Roman De Silence Evan J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Reticent romans: silence and writing in La Vie de Saint Alexis, Le Conte du Graal, and Le Roman de Silence Evan J. Bibbee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bibbee, Evan J., "Reticent romans: silence and writing in La Vie de Saint Alexis, Le Conte du Graal, and Le Roman de Silence" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3768. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3768 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. RETICENT ROMANS: SILENCE AND WRITING IN LA VIE DE SAINT ALEXIS, LE CONTE DU GRAAL, AND LE ROMAN DE SILENCE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of French Studies by Evan J. Bibbee B.A., Albion College, 1992 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 August, 2003 © Copyright 2003 Evan J. Bibbee All rights reserved ii Epigraph For if when I speak I am unable to make myself intelligible, then I am not speaking – even though I were to talk uninterruptedly day and night. — Søren Kirkegaard, Fear and Trembling Silence itself is defined in relationship to words, as the pause in music receives its meaning from the group of notes around it. -

Jurupa Unified School District Board of Education Regular Meeting Agenda

JURUPA UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT BOARD OF EDUCATION REGULAR MEETING AGENDA SLOGAN Learning Without Limits PROMISE STATEMENT By fostering a growth mindset in every child, Jurupa Unified School District empowers each child to unlock his or her potential and succeed in career, in school, and in life. We call this Learning Without Limits; the promise we make and pledge to uphold to our students, their families and our community. BOARD OF EDUCATION: Robert Garcia, President Linda Chard, Clerk Karen Bradford Memo Mendez Silvia Ortega SUPERINTENDENT: Elliott Duchon MONDAY, OCTOBER 15, 2018 BENITA B. ROBERTS EDUCATION CENTER 4850 Pedley Road Jurupa Valley, CA Call to Order in Hearing Session - President Garcia Roll Call Board Members HEARING SESSION - 5:00 p.m. PUBLIC VERBAL COMMENTS This communication opportunity is included on the agenda to allow members of the public to comment on matters listed on the Agenda for Closed Session. A second opportunity for public comments is included on the Public Session agenda as well. California law states that there shall be no action on items not shown on the published Board agenda. In compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act and Government Code Section 54954.2, if you need special assistance to participate in a district meeting or other services offered by the District, please contact the Superintendent's Office at 951-360-4168. Notification at least 48 hours prior to the meeting or time when services are needed will assist district staff in assuring that reasonable arrangements can be made to provide accessibility to the meeting or service. Agendas of public meetings and any other writings distributed to all, or a majority of, District Board Members in connection with a matter subject to discussion or consideration at an open meeting of the Board are public records. -

Don't Lose Your Mind

Making the Most of Madness in the Mad City MIND your lose This one’s for Erick. one’s This DON’T Writing • Benjamin Baugh Editing • Ryan Macklin • Fred Hicks Layout and Original System Design • Fred Hicks Art • George Cotronis • Fred Hicks ©2008 Evil Hat Productions, LLC ACS A is for ANTS 2CS B is for BREATH 3CS C is for CABBIE 4CS D is for DINO 5CS E is for EAR 6CS F is for FUCK 7CS G is for GOBLINS 8CS H is for HANDS 9CS I is for INNARDS 10CS J is for JUNGLE JCS K is for KNIFE QCS L is for LANGUAGE KCS M is for MOUTHS Red 130 Red A S is for ANTS crawling under your skin. See them burst out and creep back within! I got clean enough to add up my life, and without the junkie math scrambling my brain, it totaled rehab. Calling in the last favor I had, I got me a bed at St. Vic’s. After stripping in the intake room and taking the paper robe off, I felt pretty fucking virtuous flip-flopping down the beige hall to my room. But by the time I got there, the creepy crawlers had woken up and started nibbling and stretching under my skin. A Scratch scratch scratch When I walked in, my roomie--a guy that looked like a jello mold made in a hot tub--was in watching TV. I wondered if he had marshmallows in him. Considering his size, he probably had at least a few in there. -

Model Ifp-100/Ecs

MODEL IFP-100/ECS Analog/Addressable Fire Control Panel ECN: 11-0317 Installation and Document 151458 12/13/2011 Rev: A Operations Manual 151458:A ECN: 11-0317 Installation Procedure Installation Precautions - Adherence to the following will aid in problem-free installation with long-term reliability: WARNING - Several different sources of power can be connected to the fire alarm control panel. Disconnect all sources of power before servicing. Control unit and associated equipment may be damaged by removing and/or inserting cards, modules, or interconnecting cables while the unit is energized. Do not attempt to install, service, or operate this unit until manuals are read and understood. CAUTION - System Re-acceptance Test after Software Changes: To ensure proper system operation, this product must be tested in accordance with NFPA 72 after any programming operation or change in site-specific software. Re-acceptance testing is required after any change, addition or deletion of system components, or after any modification, repair or adjustment to system hardware or wiring. All components, circuits, system operations, or software functions known to be affected by a change must be 100% tested. In addition, to ensure that other operations are not inadvertently affected, at least 10% of initiating devices that are not directly affected by the change, up to a maximum of 50 devices, must also be tested and proper system operation verified. This system meets NFPA requirements for operation within the range of 0°C-49°C (32°F-120°F) or humidity within the range of 10%-93% at 30°C (86°F) noncondensing. However, the useful life of the system's standby batteries and the electronic components may be adversely affected by extreme temperature ranges and humidity. -

Catalogo ARTISTA TITULO for ANO OBS STOCK PVP

Catalogo ARTISTA TITULO FOR ANO OBS STOCK PVP 1927 ISH +2 CD 1989 20 th Anniversary Edition X 27,00 1927 THE OTHER SIDE CD 1990 AOR X 22,95 21 GUNS KNEE DEEP CDS 1992 Melodic Rock X 5,00 220 VOLT 220 VOLT CD Japanese Edition X 25,00 220 VOLT EYE TO EYE -Japan Edt.- CD 1988 Japan reissue remastered +2 tracks X 20,99 24 K PURE CD 2000 X 7,50 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS CD X 17,95 38 SPECIAL FLASHBACK CD 1987 Best of 16,95 38 SPECIAL ICON CD 2011 Best of X 10,95 38 SPECIAL ROCK & ROLL STRATEGY CD 20,95 38 SPECIAL STRENGTH IN NUMBERS CD 1986 X 11,99 38 SPECIAL TOUR DE FORCE CD 1983 X 10,95 38 SPECIAL WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS CD 1978 10,95 38 SPECIAL WILD-EYED SOUTHERN../SPECIAL FORCES CD 1978 1980 & 1982 2013 reissue 2 Albums 1 CD X 12,99 AB/CD CUT THE CRAO CD 12,95 AB/CD THE ROCK 'N''ROLL DEVIL CD 12,95 ABC THE CLASSIC MASTERS COLLECTION CD Best of X 12,95 AC/DC BACK IN BLACK CD 1980 2003 remastered X 14,95 AC/DC BACK IN BLACK -LTD 180G- CD 1980 2009 LTD 180G X 22,95 AC/DC BALLBREAKER CD 12,95 AC/DC BLACK ICE CD 2008 Remasters digipack X 17,95 AC/DC BONFIRE 5CD X 27,95 AC/DC DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 4DVD X 25,00 AC/DC DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP CD 1976 Remasters digipack 9,95 AC/DC FLICK OF THE SWITCH CD 12,95 AC/DC FLY ON THE WALL CD 12,95 AC/DC HELL AIN'T A BAD PLACE TO BE BOOK X 8,95 AC/DC HIGHWAY TO HELL CD 12,95 ARTISTA TITULO FOR ANO OBS STOCK PVP AC/DC HIGHWAY TO HELL -180G- LP 1979 2009 ltd 180G X 22,95 AC/DC IF YOU WANT BLOOD YOU'VE GOT IT CD 12,95 AC/DC IN CONCERT BLRY 2012 98 min X 12,95 AC/DC IT''S A LONG WAY TO THE TOP DVD X 7,50 AC/DC LET THERE BE ROCK DVD X 10,95 AC/DC LIVE 92 2LP 1992 Live X 25,95 AC/DC LIVE 92 2CD 1992 Live X 24,95 AC/DC NO BULL DVD X 12,95 AC/DC POWERAGE CD 10,95 AC/DC RAZOR'S EDGE CD 1990 Remasters digipack X 14,95 AC/DC STIFF UPPER LIP CD Remasters digipack 10,95 AC/DC T.N.T. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

The Silver Chair. (First Published 1953) by C.S

The Silver Chair C. S. L e w i s Samizdat The Silver Chair. (first published 1953) by C.S. Lewis (1895-1963) Edition used as base for this ebook: London: Geoffrey Bles, 1965 [sixth printing] Source: Project Gutenberg Canada, Ebook #1156 Ebook text was produced by Al Haines Warning : this document is for free distribution only. Ebook Samizdat 2017 (public domain under Canadian copyright law) Disclaimer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost. Copyright laws in your country also govern what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in a constant state of flux. If you are outside Canada, check the laws of your country before down- loading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or creating derivative works based on this Samizdat Ebook. Samizdat makes no claims regarding the copyright status of any work in any country outside Canada. To Nicholas Hardie Table Of Contents CHAPTER I Behind the Gym 1 CHAPTER II Jill is Given a Task 9 CHAPTER III The Sailing of the King 17 CHAPTER IV A Parliament of Owls 26 CHAPTER V Puddleglum 34 CHAPTER VI The Wild Waste Lands of the North 42 CHAPTER VII The Hill of the Strange Trenches 51 CHAPTER VIII The House of Harfang 59 CHAPTER IX How They Discovered Something Worth Knowing 67 The Silver Chair iii CHAPTER X Travels Without the Sun 75 CHAPTER XI In the Dark Castle 84 CHAPTER XII The Queen of Underland 92 CHAPTER XIII Underland Without the Queen 100 CHAPTER XIV The Bottom of the World 108 CHAPTER XV The Disappearance of Jill 116 CHAPTER XVI The Healing of Harms 124 Chapter I Behind the Gym t was a dull autumn day and Jill Pole was crying behind the gym. -

MODEL IFP-2000/ RPS-2000 Analog/Addressable Fire System

MODEL IFP-2000/ RPS-2000 Analog/Addressable Fire System Installation and Operations Manual Part Number 151430 Rev A Installation Procedure Adherence to the following will aid in problem-free installation with long-term reliability: Installation Precautions - Adherence to the following will aid in problem-free installation with long-term reliability: WARNING - Several different sources of power can be connected to the fire alarm control panel. Disconnect all sources of power before servicing. Control unit and associated equipment may be damaged by removing and/or inserting cards, modules, or interconnecting cables while the unit is energized. Do not attempt to install, service, or operate this unit until manuals are read and understood. CAUTION - System Re-acceptance Test after Software Changes: To ensure proper system operation, this product must be tested in accordance with NFPA 72 after any programming operation or change in site-specific software. Re-acceptance testing is required after any change, addition or deletion of system components, or after any modification, repair or adjustment to system hardware or wiring. All components, circuits, system operations, or software functions known to be affected by a change must be 100% tested. In addition, to ensure that other operations are not inadvertently affected, at least 10% of initiating devices that are not directly affected by the change, up to a maximum of 50 devices, must also be tested and proper system operation verified. This system meets NFPA requirements for operation within the range of 0°C-49°C (32°F-120°F) or humidity within the range of 10%-93% at 30°C (86°F) noncondensing. -

Download Marvel

DONNY CATES • RYAN OTTLEY INTERIOR ART FROM HULK #1 1 3 HULK #1 DONNY CATES (W) • RYAN OTTLEY (A/C) VARIANT COVER BY SIMONE BIANCHI VARIANT COVER BY ARTHUR ADAMS VARIANT COVER BY PEACH MOMOKO DESIGN VARIANT COVER BY RYAN OTTLEY VARIANT COVER BY TBA VARIANT COVER BY DAN JURGENS HIDDEN GEM VARIANT COVER BY HERB TRIMPE INFINITY SAGA PHASE 1 VARIANT COVER BY JOE BENNETT PURPLE VARIANT COVER ALSO AVAILABLE BLANK VARIANT COVER ALSO AVAILABLE VARIANT COVER BY PEACH MOMOKO VARIANT COVER BY SIMONE BIANCHI IMMORTAL NO LONGER! CATES & OTTLEY DELIVER INFINITY SAGA PHASE 1 VARIANT COVER A NEW, COLOSSAL-SIZED ERA! BY JOE BENNETT “MAD SCIENTIST” PART 1 OF 6 The uncontrollable rage of the Hulk has reached an all-new level, and nobody – including the Avengers – is prepared to handle it. But is it really the Hulk that people should be afraid of, or is there something missing to this puzzle? Join the superstar creative team of Donny Cates and Ryan Ottley as they look to the stars for the next era of HULK! 40 PGS./RATED T+ …$4.99 VARIANT COVER BY PEACH MOMOKO INFINITY SAGA PHASE 1 VARIANT COVER BY JOE BENNETT 5 VENOM #2 RAM V (W) • BRYAN HITCH (A/C) VARIANT COVER BY ED MCGUINNESS VARIANT COVER BY LEINIL FRANCIS YU INTERIOR ART FROM ISSUE #2 • The tour de force of comics awesomeness brought to you by the dynamite new creative team on VENOM continues! VENOM #1 shocked, intrigued and terrified you! • With Ram V and Al Ewing weaving a mind-bending story that will push Eddie and Dylan Brock to their limits, and Bryan Hitch doing some of the most action-packed -

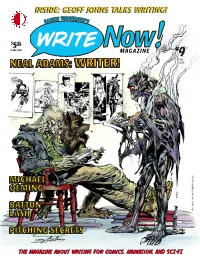

Geoff Johns Talks Writing!

IINNSSIIDDEE:: GGEEOOFFFF JJOOHHNNSS TTAALLKKSS WWRRIITTIINNGG!! $595 In the USA MAGAZINE #9 Feb 20020055 s m a d A l a e N 5 0 0 2 © s r e t s n o M ’ s m a d A l a e N TThhee MMaaggaazziinnee AAbboouutt WWrriittiinngg FFoorr CCoommiiccss,, AAnniimmaattiioonn,, aanndd SSCCII--FFII MAGAZINE Issue #9 February 2005 Read Now! Message from the Editor-in-Chief . .page 2 On Writing and Life: Interview with Neal Adams . .page 3 Master of the Universes Interview with Geoff Johns . .page 26 Counselor of the Macabre Interview with Batton Lash . .page 41 A Decent Proposal Conceived by DANNY FINGEROTH Christos N. Gage , writer of Deadshot , tells the tale of how his Editor-in-Chief proposal became a series . .page 57 Designer Feedback JOHN M cCARTHY Letters from Write Now! ’s Readers . .page 65 Transcriber STEVEN TICE Publisher JOHN MORROW Nuts & Bolts Department: COVER by Script to Finished Art: TEEN TITANS #17 NEAL ADAMS Pages from “Big Brothers and Sisters,” by Geoff Johns, Cover coloring by Mike McKone and Marlo Alquiza . .page 30 J. DAVID SPURLOCK and CORY ADAMS Neal Adams] Script to Finished Art: GREEN LANTERN: REBIRTH #1 [Neal Adams Monsters ©2005 Pages from “Blackest Night,” by Geoff Johns and Special Thanks To Ethan Van Sciver . .page 36 CORY ADAMS KRIS ADAMS Notes to Thumbnails to Layouts to Script to Finished Art: NEAL ADAMS SUPERNATURAL LAW #40 ZEEA ADAMS “13 Court Street,” by Batton Lash . .page 50 DAN BERMAN ALISON BLAIRE Script to Pencils to Finished Art: DEADSHOT #1 Pages from “Urban Renewal: Strings” by Christos N. -

INTELLIKNIGHT 5820XL 5820XL-EVS Addressable Fire System Emergency Voice System

INTELLIKNIGHT 5820XL 5820XL-EVS Addressable Fire System Emergency Voice System Document LS10061-001SK-E Installation and 01/29/2015 Rev: F Operations Manual P/N LS10061-001SK-E:F ECN: 14-0574 Installation Procedure Installation Precautions - Adherence to the following will aid in problem-free installation with long-term reliability: WARNING - Several different sources of power can be connected to the fire alarm control panel. Disconnect all sources of power before servicing. Control unit and associated equipment may be damaged by removing and/or inserting cards, modules, or interconnecting cables while the unit is energized. Do not attempt to install, service, or operate this unit until manuals are read and understood. CAUTION - System Re-acceptance Test after Software Changes: To ensure proper system operation, this product must be tested in accordance with NFPA 72 after any programming operation or change in site-specific software. Re-acceptance testing is required after any change, addition or deletion of system components, or after any modification, repair or adjustment to system hardware or wiring. All components, circuits, system operations, or software functions known to be affected by a change must be 100% tested. In addition, to ensure that other operations are not inadvertently affected, at least 10% of initiating devices that are not directly affected by the change, up to a maximum of 50 devices, must also be tested and proper system operation verified. This system meets NFPA requirements for operation within the range of 0°C-49°C (32°F-120°F) or humidity within the range of 10%-93% at 30°C (86°F) non- condensing. -

151174D, 01/03 Content

SILENT KNIGHT 5000 Series Entry System Installation and Operation Manual Part Number 151174D, 01/03 Content Section 1 Overview ...................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 User Features ............................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 What’s In the Box .................................................................................................................................... 1-2 1.3 About this Manual .................................................................................................................................... 1-2 1.3.1 Terminology ...................................................................................................................................... 1-2 Section 2 Telephone Requirements ...................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Before Connecting The Control Panel ..................................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 INDUSTRY CANADA WARNINGS ..................................................................................................... 2-2 2.2.1 AVIS D’INDUSTRIE CANADA ..................................................................................................... 2-3 Section 3 Installation Instructions ..........................................................................................................