Pink Machine Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,529,350 B2 Angelopoulos (45) Date of Patent: Sep

US00852935OB2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,529,350 B2 Angelopoulos (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 10, 2013 (54) METHOD AND SYSTEM FOR INCREASED 5,971,855 A 10/1999 Ng REALISM IN VIDEO GAMES 6,080,063 A 6/2000 Khosla 6,135,881 A 10/2000 Abbott et al. 6,200,216 B1 3/2001 Peppel (75) Inventor: Athanasios Angelopoulos, San Diego, 6,261,179 B1 T/2001 Shoto et al. CA (US) 6,292.706 B1 9/2001 Birch et al. 6,306,033 B1 10/2001 Niwa et al. (73) Assignee: White Knuckle Gaming, LLC, 6,347.993 B1 2/2002 Kondo et al. Bountiful, UT (US) 6,368,210 B1 4/2002 Toyohara et al. s 6,412,780 B1 7/2002 Busch (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2005,639 R 2. Salyean et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2002/0086733 A1* 7/2002 Wang .............................. 463/42 U.S.C. 154(b) by 882 days. OTHER PUBLICATIONS (21) Appl. No.: 12/547,359 Weters, NFL 2K1. FAQ by Weters, Hosted by GameFAQs, Version 3.1, http://www.gamefaqs.com/console? dreamcast/file/914206/ (22) Filed: Aug. 25, 2009 8841, last accessed Jul. 2, 2009. 65 P PublicationO O Dat Sychoy Bubba Crusty,y, NFL 2K1. FAQ byy Tazzmission, Hosted by (65) O DO GameFAQs, http://www.gamefacs.com/console? dreamcast/file? US 201O/OO29352 A1 Feb. 4, 2010 914206/8814, last Version 2.0, accessed Jul. 2, 2009. Related U.S. Application Data (Continued) (62) Division of application No. -

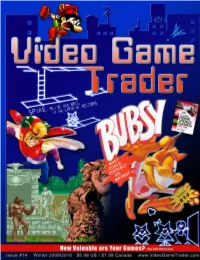

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Madden Nfl 2003 Xbox Manual

MAD03xbxMAN 7/10/02 1:27 PM Page bc2 MADDEN NFL 2003 XBOX MANUAL 40 pages + envelope 209 Redwood Shores Parkway Redwood City, CA 94065 Part #1451605 MAD03xbxMAN 7/10/02 1:27 PM Page ifc2 ABOUT PHOTOSENSITIVE SEIZURES CONTENTS A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. USING THE XBOX VIDEO GAME SYSTEM . 2 Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching USING THE XBOX CONTROLLER. 3 video games. BASIC CONTROLS . 4 These seizures may have a variety of symptoms including: lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confu- COMPLETE CONTROL SUMMARY . 5 sion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness SETTING UP THE GAME . 9 or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. MAIN MENU . 9 Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these PLAY NOW—STARTING AN EXHIBITION GAME . 9 symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— PLAYING THE GAME . 11 children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. PLAY CALL SCREEN . 11 The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by sitting farther from GAME SCREEN. 12 the television screen, using a smaller television screen, playing in a well-lit room, PAUSE MENU. 14 and not playing when you are drowsy of fatigued. -

Madden Nfl 2003 Nintendo Gamecube Manual

MADDEN NFL 2003 NINTENDO GAMECUBE MANUAL 48 pages 209 Redwood Shores Parkway Redwood City, CA 94065 Part #1451705 -1- CONTENTS GETTING STARTED. 4 COMMAND REFERENCE. 5 BASIC CONTROLS . 6 COMPLETE CONTROLS. 7 SETTING UP THE GAME. 11 MAIN MENU. 11 PLAY NOW—STARTING AN EXHIBITION GAME. 12 PLAYING THE GAME. 14 PLAYCALLING SCREEN . 14 GAME SCREEN. 15 PAUSE MENU. 18 OTHER GAME MODES . 18 MINI-CAMP . 18 FRANCHISE . 19 TOURNAMENT. 26 TWO MINUTE DRILL . 26 FOOTBALL 101 . 27 PRACTICE . 27 SITUATION . 28 FEATURES . 28 SETTINGS . 36 SAVING AND LOADING. 39 PROFILE MANAGER. 40 LIMITED 90-DAY WARRANTY . 41 -3- GETTING STARTED COMMAND REFERENCE 1. Turn OFF the Nintendo GameCube™ by pressing the POWER Button. NINTENDO GAMECUBE™ 2. Make sure a Nintendo GameCube™ Controller is plugged into the Nintendo CONTROLLER CONFIGURATIONS GameCube™ Controller Socket 1. L Button R Button 3. Press the OPEN Button to open the Disc Cover then insert the Madden NFL™ 2003 Nintendo GameCube™ Game Disc into the Z Button optical disc drive. Close the Disc Cover. Y Button Control Stick 4. Press the POWER Button to turn ON the Nintendo GameCube™ and X Button proceed to the Madden NFL 2003 title screen. If you can’t proceed to the title screen, begin again at step 1. A Button 5. At the Madden NFL 2003 title screen, press start to advance to the Main menu (➤ p. 11). B Button For more information on Madden NFL 2003 and other EA SPORTS™ titles, visit EA SPORTS on the Web at START / PAUSE ✚ Control Pad C Stick www.easports.com. MADDEN CONNECTED MENU CONTROLS ® ™ Connect your Nintendo Game Boy Advance to the Nintendo GameCube Highlight menu item ✚Control Pad or Control Stick Up/Down with a Nintendo GameCube™ - Game Boy® Advance cable and experience Change highlighted item ✚Control Pad or Control Stick Left/Right Madden NFL Football like never before. -

Aias Annual Awards

1st ANNUAL AWARDS / 1998 2nd ANNUAL AWARDS / 1999 3rd ANNUAL AWARDS / 2000 4st ANNUAL AWARDS / 2001 5nd ANNUAL AWARDS / 2002 Golden Eye 007 The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time The Sims Diablo II Halo: Combat Evolved Interactive Title of the Year Game of the Year Game of the Year Game of the Year Game of the Year Starcraft Half-Life Age of Empires II: Age of Kings Diablo II Black & White Computer Game of the Year Computer Game of the Year Computer Game of the Year PC Game of the Year Computer Game of the Year Golden Eye 007 The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time Soul Calibur SSX Halo: Combat Evolved Console Game of the Year Console Game of the Year Console Game of the Year Console Game of the Year Console Game of the Year Riven: The Sequel to Myst Banjo-Kazooie Final Fantasy VIII Deus Ex Advance Wars Outstanding Achievement in Art/Graphics Outstanding Achievement in Art/Graphics Outstanding Achievement in Animation Computer Innovation Hand-Held Game of the Year Parappa the Rapper Pokemon Final Fantasy VIII Shenmue Black & White Outstanding Achievement in Interactive Design Outstanding Achievement in Character or Story Development Outstanding Achievement in Art Direction Console Innovation Computer Innovation Parappa the Rapper The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time Age of Empires II: Age of Kings Final Fantasy IX Pikmin Outstanding Achievement in Sound and Music Outstanding Achievement in Interactive Design Outstanding Achievement in Character or Story Development Animation Console Innovation Golden Eye 007 Road Rash 3D The Sims Final Fantasy -

The Monstrous Madden Playbook Offense Volume I

The Monstrous Madden Playbook Offense Volume I Matt Heinzen This book and its author have no affiliation with the National Football League, John Madden, or the Madden NFL 2003 or Madden NFL 2004 video games or their publisher, EA Sports. The author has taken care in preparation of this book, but makes no warranty of any kind, expressed or implied, and assumes no responsibility for any errors contained within. No liability is assumed for any damages resulting through direct or indirect use of this book’s contents. Copyright c 2003 by Matt Heinzen All rights pertaining to distribution or duplication for purposes other than per- sonal use are reserved until October 15, 2008. At this time the author voluntarily removes all restrictions regarding distribution and duplication of this book, al- though any modified version must be marked as such while retaining the original author’s name, the original copyright date and this notice. Visit my Madden NFL Playbook web sites at monsterden.net/madden2003/ and monsterden.net/madden2004/ and my forums at monsterden.net/maddentalk/. Contents 1 Introduction 1 Offensive Philosophy ........................... 1 Creating New Formations ......................... 3 Creating New Plays ............................ 6 Specialty Plays .............................. 6 Using This Book Effectively ....................... 7 Abbreviations ............................... 8 2 Diamond Wing 9 Delay Sweep ............................... 10 Flurry ................................... 13 Counter Sweep ............................. -

July 2010 More Than Just a Game

For more than 20 years, it has been embraced by its fans, honored by critics, and envied by its rivals. It has endured the test of time and has satisfied a demanding public like no other sports video game in history. It’s been recognized as ‘the game the players play,’ ‘the benchmark in sports video gaming,’ and ‘the number one selling football video game in history.’ It is Madden NFL. Since its inception, the Madden NFL franchise has reigned supreme as the preeminent sports title in the video game industry. Sales of more than 85 million units worldwide and $3 billion in lifetime revenue along with a countless number of gaming awards have helped make Madden NFL the most critically acclaimed sports title in history. From the original John Madden Football, released by Electronic Arts in 1989, to last season’s award-winning Madden NFL 10, the franchise has found a permanent home atop the video game pedestal. With record-breaking numbers that scream off the charts, there is little doubt about Madden NFL’s effect on the consumer—sports fans love it, hardcore football fans fawn over it, and NFL players deeply respect it. What started as a simple idea many years ago has profoundly affected today’s pop culture in many ways. On the field, the game dominates the virtual gridiron. Off the field, its popularity is growing larger by the year. ™ Backed by events like the EA SPORTS Madden Bowl, EA SPORTS™ takes a look at the EA SPORTS™ Madden Challenge, Maddenoliday, Maddenpalooza, Pigskin Pro-Am, and Madden Gras, past, present and future of the Madden NFL is no longer ‘just a game.’ The Madden NFL franchise. -

Sony Playstation 2

Sony PlayStation 2 Last Updated on September 28, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments .hack//G.U. Vol. 1//Rebirth Namco Bandai Games .hack//G.U. Vol. 1//Rebirth: Demo Namco Bandai Games .hack//G.U. Vol. 1//Rebirth: Special Edition Bandai Namco Games .hack//G.U. Vol. 2//Reminisce Namco Bandai Games .hack//G.U. Vol. 3//Redemption Namco Bandai Games .hack//Infection Part 1: Demo Bandai .hack//Infection Part 1 Bandai .hack//Mutation Part 2 Bandai .hack//Mutation Part 2: Trade Demo Bandai .hack//Mutation Part 2: Demo Bandai .hack//Outbreak Part 3: Demo Bandai .hack//Outbreak Part 3 Bandai .hack//Quarantine Part 4 Bandai .hack//Quarantine Part 4: Demo Bandai 007: Agent Under Fire Electronic Arts 007: Agent Under Fire: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 007: Everything or Nothing Electronic Arts 007: Everything or Nothing: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 007: Everything or Nothing: Demo Electronic Arts 007: Nightfire Electronic Arts 007: Nightfire: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 007: Quantum of Solace Activision 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker Acclaim 187 Ride or Die Ubisoft 2002 FIFA World Cup Electronic Arts 2006 FIFA World Cup EA Sports 24: The Game 2K Games 25 to Life Eidos 4x4 Evolution Godgames 50 Cent: Bulletproof Vivendi Universal Games 50 Cent: Bulletproof: Greatest Hits Vivendi Universal Games 7 Wonders of the Ancient World MumboJumbo 989 Sports 2004 Disc: Demo 989 Sports 989 Sports Sampler 2003: Demo 989 Sports AC/DC Live: Rock Band Track Pack MTV Games Ace Combat 04: Shattered Skies Namco Ace Combat 04: Shattered Skies: Greatest Hits -

Matthew Marquez the History of Video Game Design Prof

Matthew Marquez The History of Video Game Design Prof. Henry Lowood March 18, 2003 If it’s in the game, it’s in the game! The Evolution of Madden Football: Electronic Arts Sports is the current leader in football video games with an 85% share of the market [gameinfowire.com], largely due to the continued success of the John Madden Football Series. Since it’s first release in 1989 on the Apple II, Madden Football has consistently topped competitors on every gaming platform. Last year’s edition, Madden NFL 2002, sold over 4 million units on seven different platforms while the entire series has sold over 25 million units since 1989 [EA Press Release 236]. Madden Football has achieved a reputation and market share few video game franchises can ever hope to attain, and has spawned numerous competitors at every step of its evolution. How has Madden remained so competitive 14 years after its initial release? Obviously Madden Football has consistently brought innovative new features and gaming concepts onto the virtual playing field, and by looking at the sometimes gradual and sometimes drastic changes in the series, a clear trend towards increased realism emerges. Madden games have pushed the designs of realistic player animations and behavior, NFL based play calling systems, and most recently and certainly most exciting is the now ubiquitous franchise mode where gamers can take their chosen team through dozens of seasons - cutting, trading, and drafting players to their hearts’ content. In addition to its own innovations, perhaps the Madden series owes its continued popularity to the successful integration of its competitors’ greatest advances. -

Game Review For

Game Review for Madden NFL™ 2003 Rami Hamadeh September 23, 2002 CIS 487 Fall 2002 Dr. Bruce Maxim Basic Information for Madden NFL™ 2003 Game title Madden NFL™ 2003 for PC. (Game is also available on Xbox, Playstation 1 and 2, Gameboy, and GameCube). Company & Author Tiburon and Electronic Arts Type of game Sports Simulation – Professional Football Price $39.95 for PC Minimum stated hardware requirements • Windows XP, ME, 2000, 98 • 400 MHz Intel Pentium 2 processor • 64 MB RAM (128 for Windows 2000 and XP) • 8X CD-Rom or DVD drive • 75 MB free hard disk space plus space for saved games (Additional required for Windows swap-file and DirectX 8.0 installation) • 16 MB Direct3D capable video card using any of: Nvidia GeForce 2, 3, 4 and 256, Riva TNT 1 and 2, ATI Radeon 1, 8500, and 7500, or Matrox G550, G450, and G400 with DirectX 8.0 compatible driver • DirectX 8.0 compatible sound card • Keyboard • Mouse Actual hardware required • 600 MHz or faster Pentium 3 or Athlon processor • 128 MB or more RAM • 650 MB or more free hard disk space • 32 MB or greater supported Direct3D capable Video Card with DirectX 8.0 compatible driver • Supported gamepad • 56Kbps or faster internet connection for internet multiplayer games • TCP/UDP compliant network for LAN multiplayer games 1 Game Summary of Madden NFL™ 2003 Quick overview Madden NFL™ 2003 is the latest version of the John Madden Football series that dates back about 14 years. The series has always delivered the most authentic, most realistic football game with unmatched feature sets and detail, and this definitely continues with Madden NFL™ 2003. -

1 What's the Future for Nintendo? Joshua Gutman Randolph Tjoa

What’s the future for Nintendo? Joshua Gutman Randolph Tjoa Bradley Westover 1 Today, Nintendo finds itself in a position it has rarely held in the time it has competed in the home console market: the underdog. Sales of its current generation GameCube console are far behind sales of the previous generation’s Nintendo 64, owing to the fierce competition from its two main rivals, Microsoft with its Xbox console, and Sony, with its PlayStation 2. However, there is still potential for profit for Nintendo in the home console market if it implements a strategy that draws on the company’s strengths and prevents its competitors from exploiting its weaknesses. The company must first decide on an effective marketing strategy, and then choose to develop software and hardware that the target audience finds appealing. Strengths One of Nintendo’s strengths is its earlier contact with consumers. Since Nintendo has a younger demographic it potentially has the ability to lock in a customer base starting at an early age. Also, Nintendo has the reputation of having more kid- friendly games, which is important to parents. Nintendo can exploit synergies between its successful handheld gaming systems and its consoles. Nintendo also has numerous game characters that have appeared in the company’s software for years and have strong recognition among consumers. Weaknesses Nintendo’s strength among younger players has cost them among older players, however. Nintendo has a low popularity in what has become the majority of the market with teen and adult gamers, a market which Sony and Microsoft share. Nintendo’s lower price means that they generally have less powerful systems.