Interactive and Adaptive Audio for Home Video Game Consoles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cord Weekly

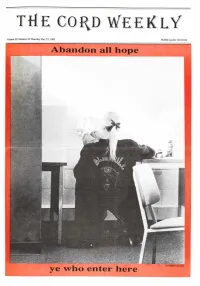

THE CORD WEEKLY Volume 29, Number 25 Thursday Mar. 23,1989 Wilfrid Laurier University Abandon all hope ye who enter here Cord Photo: Liza Sardi The Cord Weekly 2 Thursday, March 23,1989 THE CORD WEEKLY |1 keliv/f!rent-a-car ; SAVE $5.00 ! March 23,1989 Volume 29, Number 25 ■ ON ANY CAR RENTAL ■ I Editor-in-Chief Cori Ferguson ■ NEWS Editor Bryan C. Leblanc Associate Jonathan Stover Contributors Tim Sullivan Frances McAneney COMMENT ■ ■ Contributors 205 WEBER ST. N. Steve Giustizia l 886-9190 l FEATURES Free Customer Pick-up Delivery ■ Editor vacant and Contributors Elizabeth Chen ENTERTAINMENT Editor Neville J. Blair Contributors Dave Lackie Cori Cusak Jonathan Stover Kathy O'Grady Brad Driver Todd Bird SPORTS Editor Brad Lyon Contributors Brian Owen Sam Syfie Serge Grenier Lucien Boivin Raoul Treadway Wayne Riley Oscar Madison Fidel Treadway Kenneth J. Whytock Janet Smith DESIGN AND ASSEMBLY Production Manager Kat Rios Assistants Sandy Buchanan Sarah Welstead Bill Casey Systems Technician Paul Dawson Copy Editors Shannon Mcllwain Keri Downs Contributors \ Jana Watson Tony Burke CAREERS Andre Widmer 112 PHOTOGRAPHY Manager Vicki Williams Technician Jon Rohr gfCHALLENGE Graphic Arts Paul Tallon Contributors Liza Sardi Brian Craig gfSECURITY Chris Starkey Tony Burke J. Jonah Jameson Marc Leblanc — ADVERTISING INFLEXIBILITY Manager Bill Rockwood Classifieds Mark Hand gfPRESTIGE Production Manager Scott Vandenberg National Advertising Campus Plus gf (416)481-7283 SATISFACTION CIRCULATION AND FILING Manager John Doherty Ifyou want theserewards Eight month, 24-issue CORD subscription rates are: $20.00 for addresses within Canada inacareer... and $25.00 outside the country. Co-op students may subscribe at the rate of $9.00 per four month work term. -

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive A Change is Gonna Come: The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies And Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of Masters of Laws in the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Kurt Dahl © Copyright Kurt Dahl, September 2009. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean of the College of Law University of Saskatchewan 15 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A6 i ABSTRACT The purpose of my research is to examine the music industry from both the perspective of a musician and a lawyer, and draw real conclusions regarding where the music industry is heading in the 21st century. -

Funcom Secures €5 Million in Financing from Nordic Venture Partners

Funcom secures €5 million in financing from Nordic Venture Partners Durham, USA – August 25, 2005 – Funcom, a world leading developer and publisher of subscription-based online games like ‘Anarchy Online’ and ‘Age of Conan – Hyborian Adventures’, has secured a €5 million equity investment from Nordic Venture Partners (NVP). The investment is a further testament to Funcom being a world-class developer and publisher of online games, and will further aid the company in developing and publishing online games. “This is another great recognition of Funcom as Europe’s premier developer of MMOG’s (Massively Multiplayer Online Games), and serves as a tribute to the company and the quality of our games and technology” said Torleif Ahlsand, Chairman of the Board of Directors in Funcom and Partner in Northzone Ventures. ”There is a considerable market potential for subscription- based online games, and Funcom is a leader in technology and quality within the segment. We are very glad to have NVP on board to further develop one of the most exciting creative environments in the Nordic region, and we feel confident they will aid us in becoming even better at creating world-class online products.” “Being one of the leading information and communication technology investments funds in the Nordic region we are only looking for the very best technology companies, and we feel confident Funcom fits great in our portfolio” said Claus Højbjerg Andersen, Partner in NVP and new Boardmember of Funcom. “We are convinced of Funcom’s unique quality and their world-class staff and technology. Our aim is to improve the business side of Funcom even further, thus supporting the company in realizing their creative visions. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Brittany Tuvo Su Muerte Asistida La Joven Estadounidense Sufría Un Cáncer Terminal Y Reavivó El Debate Sobre La Eutanasia

Sociedad Brittany tuvo su muerte asistida La joven estadounidense sufría un cáncer terminal y reavivó el debate sobre la eutanasia. "Murió en paz, rodeada por su familia", informó la ONG que la asesoraba. pág. 32-33 www.tiempoargentino.com | año 5 | nº 1614 | martes 4 de noviembre de 2014 edición nacional | $ 8 | recargo envío al interior $ 1,50 | ROU $ 40 MAR 4 MAR HAY 19 DISTRITOS DE LA PROVINCIA DE BUENOS AIRES AFECTADOS POR LA LLUVIA Y LA SUDESTADA DE LOS ÚLTIMOS DÍAS Más de 5200 evacuados por el fuerte temporal Las zonas más perjudicadas son La Matanza, Pilar y Tigre. En sólo tres días cayeron 145 milímetros de agua en el área metropolitana, un 35% más que el promedio histórico de todo noviembre. En Luján, la situación es "catastrófica". pág. 30-31 Soros pidió a la Junto al fondo de inversión de » ESPECTÁCULOS pág. SE Juan Simón, mánager de Boca justicia inglesa Kyle Bass, solicitó que se liberen "Ganar la Copa los pagos de deuda argentina nuevo ciclo en encuentro que declare nulo bajo leyes europeas, bloqueados El compromiso de Sudamericana el fallo de Griesa por el juez de Nueva York. pág. 4-5 salvaría el año" Agustina Cherri La actriz es la voz de Afirma que el hincha Confirman que tiene una infección y continúa internada "quiere resultados" Cristina Historias de y que no salir género, una serie campeón es un » POLICIALES pág. 40 » POLÍTICA pág. 10 » MUNDO pág. 22-23 documental sobre "fracaso". Y dice violencia de género. apuntan a prófugo del caso bonfatti duro cruce por las inundaciones para mantener control del senado que el equipo "Puedo unir lo del Vasco Conmoción por crimen de Scioli acusó a Massa de Obama enfrenta hoy una social con lo se estancó. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,529,350 B2 Angelopoulos (45) Date of Patent: Sep

US00852935OB2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,529,350 B2 Angelopoulos (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 10, 2013 (54) METHOD AND SYSTEM FOR INCREASED 5,971,855 A 10/1999 Ng REALISM IN VIDEO GAMES 6,080,063 A 6/2000 Khosla 6,135,881 A 10/2000 Abbott et al. 6,200,216 B1 3/2001 Peppel (75) Inventor: Athanasios Angelopoulos, San Diego, 6,261,179 B1 T/2001 Shoto et al. CA (US) 6,292.706 B1 9/2001 Birch et al. 6,306,033 B1 10/2001 Niwa et al. (73) Assignee: White Knuckle Gaming, LLC, 6,347.993 B1 2/2002 Kondo et al. Bountiful, UT (US) 6,368,210 B1 4/2002 Toyohara et al. s 6,412,780 B1 7/2002 Busch (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2005,639 R 2. Salyean et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2002/0086733 A1* 7/2002 Wang .............................. 463/42 U.S.C. 154(b) by 882 days. OTHER PUBLICATIONS (21) Appl. No.: 12/547,359 Weters, NFL 2K1. FAQ by Weters, Hosted by GameFAQs, Version 3.1, http://www.gamefaqs.com/console? dreamcast/file/914206/ (22) Filed: Aug. 25, 2009 8841, last accessed Jul. 2, 2009. 65 P PublicationO O Dat Sychoy Bubba Crusty,y, NFL 2K1. FAQ byy Tazzmission, Hosted by (65) O DO GameFAQs, http://www.gamefacs.com/console? dreamcast/file? US 201O/OO29352 A1 Feb. 4, 2010 914206/8814, last Version 2.0, accessed Jul. 2, 2009. Related U.S. Application Data (Continued) (62) Division of application No. -

Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2008-03-28 Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship Bradley R. Clark Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Clark, Bradley R., "Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 1350. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1350 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Using the ZMET Method 1 Running head: USING THE ZMET METHOD TO UNDERSTAND MEANINGS Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship Bradley R Clark A project submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Brigham Young University April 2008 Using the ZMET Method 2 Copyright © 2008 Bradley R Clark All Rights Reserved Using the ZMET Method 3 Using the ZMET Method 4 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a project submitted by Bradley R Clark This project has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. -

VAGRANT RECORDS the Lndie to Watch

VAGRANT RECORDS The lndie To Watch ,Get Up Kids Rocket From The Crypt Alkaline Trio Face To Face RPM The Detroit Music Fest Report 130.0******ALL FOR ADC 90198 LOUD ROCK Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS Talkin' Dirty With Matt Zane No Motiv 5319 Honda Ave. Unit G Atascadero, CA 93422 HIP-HOP Two Decades of Tommy Boy WEEZER HOLDS DOWN el, RADIOHEAD DOMINATES TOP ADDS AIR TAKES CORE "Tommy's one of the most creative and versatile multi-instrumentalists of our generation." _BEN HARPER HINTO THE "Geggy Tah has a sleek, pointy groove, hitching the melody to one's psyche with the keen handiness of a hat pin." _BILLBOARD AT RADIO NOW RADIO: TYSON HALLER RETAIL: ON FEDDOR BILLY ZARRO 212-253-3154 310-288-2711 201-801-9267 www.virginrecords.com [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2001 VIrg. Records Amence. Inc. FEATURING "LAPDFINCE" PARENTAL ADVISORY IN SEARCH OF... EXPLICIT CONTENT %sr* Jeitetyr Co owe Eve« uuwEL. oles 6/18/2001 Issue 719 • Vol 68 • No 1 FEATURES 8 Vagrant Records: become one of the preeminent punk labels The Little Inclie That Could of the new decade. But thanks to a new dis- Boasting a roster that includes the likes of tribution deal with TVT, the label's sales are the Get Up Kids, Alkaline Trio and Rocket proving it to be the indie, punk or otherwise, From The Crypt, Vagrant Records has to watch in 2001. DEPARTMENTS 4 Essential 24 New World Our picks for the best new music of the week: An obit on Cameroonian music legend Mystic, Clem Snide, Destroyer, and Even Francis Bebay, the return of the Free Reed Johansen. -

Design Guidelines for Audio Games

Design Guidelines for Audio Games Franco Eusébio Garcia and Vânia Paula de Almeida Neris Federal University of Sao Carlos (UFSCar), Sao Carlos, Brazil {franco.garcia,vania}@dc.ufscar.br Abstract. This paper presents guidelines to aid on the design of audio games. Audio games are games on which the user interface and game events use pri- marily sounds instead of graphics to convey information to the player. Those games can provide an accessible gaming experience to visually impaired play- ers, usually handicapped by conventional games. The presented guidelines resulted of existing literature research on audio games design and implementa- tion, of a case study and of a user observation performed by the authors. The case study analyzed how audio is used to create an accessible game on nine au- dio games recommended for new players. The user observation consisted of a playtest on which visually impaired users played an audio game, on which some interaction problems were identified. The results of those three studies were analyzed and compiled in 50 design guidelines. Keywords: audio games, accessibility, visual impairment, design, guidelines. 1 Introduction The evolution of digital interfaces continually provides simpler, easier and more intui- tive ways of interaction. Especially in games, the way a player interacts with the system may affect his/her overall playing experience, immersion and satisfaction. Currently, game interfaces mostly rely on graphics to convey information to the play- er. Albeit being an effective way to convey information to the average user, graphical interfaces might be partially or even totally inaccessible to the visually impaired. Those users are either unable or have a hard time playing a conventional game, as the graphical content of the user interface is usually essential to the gameplay.